25 Jan 2016 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

In response to the attacks on Tolo TV on 20 January, in which eight people have been killed and 30 others injured, we stand in solidarity with the Afghan media community. We condemn this and all other attacks on Afghanistan’s journalists unreservedly and applaud their courage to stand together undeterred by those who seek to silence them. We want to tell our colleagues throughout Afghanistan they are not alone; the international community is behind them. The journalists and media workers of Afghanistan are playing a leading role in working fearlessly to ensure that the voices of violent extremists do not dominate the news agenda. We remain ready to help them in this perilous endeavour.

Signed by (and including links to additional statements on the Tolo attack from these organizations),

Article 19, UK

Committee to Protect Journalists, USA

Free Press Unlimited, Netherlands

Index on Censorship, UK

Institute for War and Peace Reporting, UK

International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX), Canada

International News Safety Institute UK

International Media Support, Denmark

International Press Institute, Austria

World Association of Newspapers, France

Open Society Foundations, Program on Independent Journalism, UK

Reporters Without Borders, France

Rory Peck Trust, UK

6 Mar 2015 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, mobile, News

Last year, authorities in the east of Afghanistan decided to shut down a cemetery. The problem was that this particular cemetery was not just a final resting place; it had taken on a second function as a marketplace where women in the city could meet and trade. With the closure, the financial lifeline the women had created for themselves, was cut. There were some protests, the story was covered in a local newspaper, and that was it.

Afghan media has experienced a significant growth spurt over the past years. In 2000, the country was home to 15 news outlets; in 2014 the figure was just shy of 1,000. Hidden within these numbers is another slowly expanding subcategory. Of around 12,000 working journalists in Afghanistan today, some 2,000–2,500 are women, up from an estimated 1,000 in 2006. The truly vital role these women play in Afghan society is too often overlooked.

In a country where traditional cultural norms still hold significant sway, strict limitations on contact between the sexes continue to be enforced in many areas. As a result, there are spaces only female journalists have access to, grievances only female journalists can be told and important realities of women’s lives that only female journalists can report on. Where women media workers are few and far between, such stories — like in the case of the cemetery closure — go underreported, or are buried entirely.

“Covering and focusing on women’s issues is always my favourite, and when I produce programs and make reports on these issues, I really like it and think I’ve done something important,” Radio Sahar Station Manager Humaira Habib told Index. Radio Sahar is part of Parwana (butterfly), a network of radio stations dotted around Afghanistan, which focuses on stories that impact women and their rights and needs. And from the managerial to the executive level, they are all-female operations.

Habib says she made the decision to go into journalism in 2002, and was influenced by the plight of women under the Taliban. “I thought journalism was a good tool to reach to all the aims and goals, and to solve the problems and challenges of women. I think media plays a very important role in informing citizens,” she explained. “This was the reason I decided to study journalism.”

But while the long view seems to suggest the number of Habib’s female compatriots will continue to grow, serious challenges and setbacks remain the reality in the shorter term.

Part of the problem is that the same traditional norms that make female journalist’s contribution especially valuable, still present a significant barrier to many women joining the media industry. As reporter Zarghona Salihi told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, journalism is widely viewed as “immoral work” that carries with it social stigma for women.

“Parents don’t permit their daughters to become journalists [in particular] because female journalists soon turn popular and that puts them in lots of troubles,” news radio host Haseena Ahmadi told Voice of America.

Another, more direct and overt challenge is the seemingly worsening security situation for media workers in general, and the particular threats faced by women. Since 2001, 49 journalists have been killed, and attacks went up 64 per cent from 2013 to 2014, according to a recent report from Human Rights Watch. What’s more, they face a multi-pronged assault — from the government and local authorities, as well as from war lords and the Taliban. Meanwhile, impunity for such crimes persists.

Women must deal with all this, and then some. “Female journalists face particularly formidable challenges. Social and cultural restrictions limit their mobility in urban as well as rural areas, and increase their vulnerability to threats and attacks, including sexual violence,” the Human Rights Watch report states. Since 2010, three female journalists have been killed, including 26-year old Palwasha Tokhi, stabbed to death outside her house in September last year. The Afghan Journalists Safety Committee says that “dozens have been intimidated to stop working”. In 2013, Shaffiqa Habibi, director of the Afghan Women Journalist Union, estimated that 300 professional female journalists had stopped working due to safety concerns.

“The big challenge that journalists face here is the security problem. That really hurts us,” agrees Habib. In 2004 she was threatened by authorities and told she could never again work as a journalist in the western province of Herat. But she fought back, and today continues to hold a senior role at a radio station in that province. As one young journalist told International Media Support: “I have been threatened by the Taliban, corrupt authorities, warlords and even the government. But none of these threats will ever stop me from what I do.”

The struggle, however, doesn’t end by challenging traditions and braving a volatile security situation. Female journalists in Afghanistan are also facing a problem familiar to women all over the world: they’re simply not getting the chances their male counterparts are. On this point, international media has failed Afghanistan’s women reporters. While Amie Ferris-Rotman was working as Reuters’ Afghanistan correspondent, she realised that none of the foreign news outlets hired Afghan female correspondents, in any capacity.

“I found this hypocritical,” she told Index. “We put out a plethora of stories on women’s rights and the awful hurdles Afghan women face, yet we did not take the extra step to hear their stories in a professional context.”

Pointing to the continued prevalence of separation between the genders, she argues that by not giving a platform to female Afghan journalists, we are missing the full story. The journalists, meanwhile, are denied good networks and professional opportunities to further their careers. To help rectify this situation, Ferris-Rotman has set up the Sahar Speaks programme, to offer training and mentoring by peers from around the world to Afghan female journalists, with the aim of helping them produce stories to be published by international outlets. As she has written about the project: “Imagine how rich and nuanced the other side of the Afghan story can be, if told by its own women, not by Afghan men or foreign reporters.”

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar, the director of media freedom advocacy group Nai, which is behind the Parwana network, believes it to be very important that Afghanistan’s female reporter pool continues to grow. Certain topics, he explains, are still considered by some to be taboo for men to cover. He mentions literacy rates among women, violations against women and how women are treated both in rural and urban areas as examples of stories that “raised the need of having women journalists to report”.

Habib stresses the importance of increasing the number of female reporters outside the bigger cities, where many women’s issues that male journalists have limited access to, go uncovered. This is a “serious problem” she says, adding that “we need to train girls from those places to at least learn basic journalism to cooperate with local and national media”.

Despite the challenges, Khalvatgar, who has been nominated for an Index award for his media freedom campaigning in Afghanistan, is confident that there is enthusiasm among women to work in the sector. He points to his experience of visiting journalism schools and seeing a higher number of female than male students, as one indicator. “There are a lot of hopes and wishes among women to become journalists,” he says.

Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani vowed during his 2014 election campaign to uphold freedom of expression and protect journalists against abuse. Whether he will stick to his promise down the line, so the enthusiasm Khalvatgar speaks about can truly be harnessed, remains to be seen. What is clear, is that without more women feeling encouraged and safe enough to join Habib and her colleagues in their work, important stories will continue to go untold.

This article was posted on March 6, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

4 Mar 2015 | Afghanistan, Awards, mobile

Campaigning nominee Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar is an Afghan journalist and the executive director of the media advocacy group Nai Supporting Open Media in Afghanistan, which works to develop a free media as the country develops a peacetime society. A radio journalist for more than 10 years, he began his career with the Internews Network in 2002 and then as general manager for a national radio channel, Salam Watander.

Khalvatgar has been a tireless campaigner for a free and fair Afghan media. Nai is the only organisation in the country to monitor violence against Afghan journalists. It has offered basic training to around 10,000 Afghan journalists, teaching investigative reporting, TV hosting and technical skills. Nai also runs a network of all-female radio stations, which Khalvatgar helped set up.

The Afghan media sector has grown from having only 15 media outlets in 2000 to almost 1,000 in 2014. With this growth, new challenges have arisen. Since 2001 more than 40 journalists have been killed in Afghanistan and hundreds of attacks on members of the press have been recorded. Many of these are believed to have been perpetrated by the government. Operating in a well-documented atmosphere of violence and hostility, Khalvatgar aims to strengthen Afghan democracy by being one of the founding fathers of a free media in the country.

“The problem here is that on the one hand, the government of Afghanistan are trying to push and pressurise as much as possible the environment for free expression and free media. On the other hand the terrorists, the Taliban, are trying to silence the people who are working as journalists, who are working as media activists and those who are trying to support them,” Khalvatgar told Index on Censorship.

Her says insecurity is one of the main problems facing Afghan journalists. “Just 20 kilometres outside of Kabul it is sometimes not possible to report on what is going on,” he says, adding that outside the big cities, journalist have to self-censor for fear of the local government, local powers, and in south and east of the country, the Taliban. Even in big cities, he explains, it is sometimes difficult to investigate stories related to corruption in depth “because you don’t feel safe to do it”. He also highlights impunity for crimes against members of the press, the undefined relationship between media owners and journalists and the lack of access to information as challenges to media freedom.

Khalvatgar joined Nai as executive director in 2010, a position he still holds. He is part of Afghanistan’s Foundation Open Society Institute, working as media coordinator and acting country manager, as well as an active member of Access to Information Law Working Group, a collective of more than 15 media professionals and activists working for better access to information law in Afghanistan. He spent the better part of 2012 successfully campaigning to get a government draft law withdrawn that would have dampened media freedom and given more power over the press to conservative bodies. He also helped launch Afghanistan’s first media awards, as well as its Legacy Fund, which raises money for families of Afghan reporters who have been killed. And he is doing this work at great personal risk.

“I have had threats from Taliban that they want to kill me; threats from the government of Afghanistan that I do not criticise the government; threats from the local powers to not touch the kind of hegemonies that they have,” he lists. “But I do believe in what I’m doing. And I do love what I’m doing. So any kind of threats will not stop me.”

Khalvatgar says he is delighted about the Index award nomination, but true to form, his focus on is on his country’s media community. “If I win this award, it is an award for the people; for 49 journalists who have been killed in Afghanistan, for their families, for the almost 12,000 people that are working in the media sector in Afghanistan.”

This article was posted on March 4 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Dec 2013 | News, Politics and Society

Journalists are known for uncovering the truth. What is less known is how these journalists gather these facts, often risking their jobs, and sometimes their lives, to discover information others are attempting to keep hidden from the world.

The Taksim Gezi Park Protest

The Gezi Park protest in Turkey made international news when, in May 2013, a sit-in at the park protesting plans to develop the area sparked violent clashes with police. What didn’t grab the attention of media workers worldwide was that at least 59 of their fellow journalists were fired or forced to quit over their reporting of the events.

The Turkish press have been long-time sufferers of the need to self-censor in an environment where the press is ultimately run by a handful of wealthy individuals. The Gezi Park protests saw a surge in the controlling influence of the Turkish media as 22 journalists were fired and a further 37 forced to quit due to their determination to cover the clashes for a national and international audience, as was their duty as journalists.

Turkey came in at 154th in the Reporters Without Borders Freedom of the Press Index 2013, a drop of six places from 2012.

Journalists imprisoned

2013 was the first year a detailed survey was carried out by Reporters Without Borders which looked into how many journalists had been imprisoned for their work; the result was shocking. One hundred and seventy eight journalists were spending time in jail for their actions, along with 14 media assistants. Perhaps more worrying was the statistic that 166 netizens had been imprisoned, those who actively supply the world with content often without being paid whilst gaining access to places that many ‘official’ journalists are banned from.

China handed out the most prison sentences during 2013 with 30 media personal serving time behind bars. Closely behind was Eritrea with 28 journalists imprisoned, Turkey with 27, and Iran and Syria handing out 20 sentences each.

Press freedom in Afghanistan

Murder, injuries, threats, beatings, closure of media organisations, and the dismissal for liking a Facebook post have all accounted towards the 62 cases of violence against the media and journalists working in Afghanistan over the past eight months. The Afghanistan Journalists Center, which collected the data from January to August 2013, has claimed that government officials and security forces, the Taliban, and illegal armed groups are behind the majority of attacks.

Of particular concern is the growing threat to female journalists who have been forced to quit their jobs after threats to their families.

According to the Afghanistan Media Law; every person has the right to freedom of thought and speech, which includes the right to seek, obtain and disseminate information and views within the limit of law without any interference, restriction and threat by the government or officials- a law Afghanistan does not appear to be upholding.

Exiled journalists

Some journalists are taking a risk every day that they go to work. They may not be killed for their reporting but that does not stop them facing imprisonment, violence, and harassment. Between June 2008 and May 2013 the CPJ found that 456 journalists were forced into exile as a means of protecting their families and themselves due to their determination to uncover the truth.

The top countries from which journalists fled included Somalia, Ethiopia and Sri Lanka with Iran topping the table having forced a total of 82 journalists into exile. Although a majority of these journalists claim sanctuary in countries like Sweden, the U.S and Kenya, only 7% of those exiled since 2008 have been able to return home.

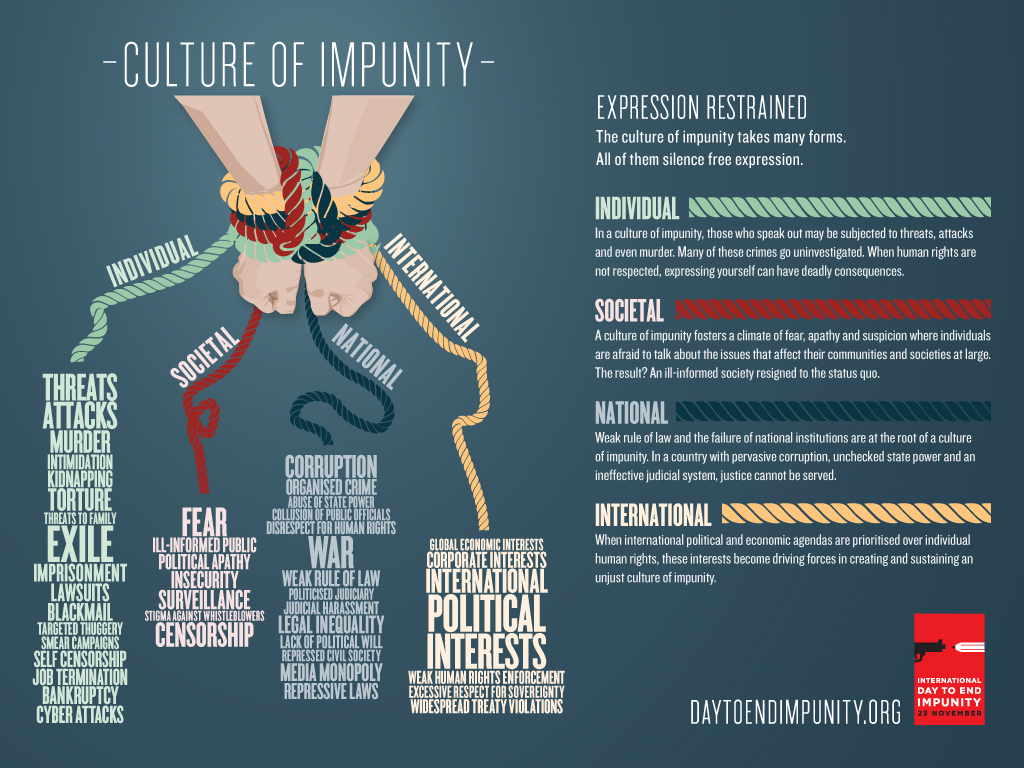

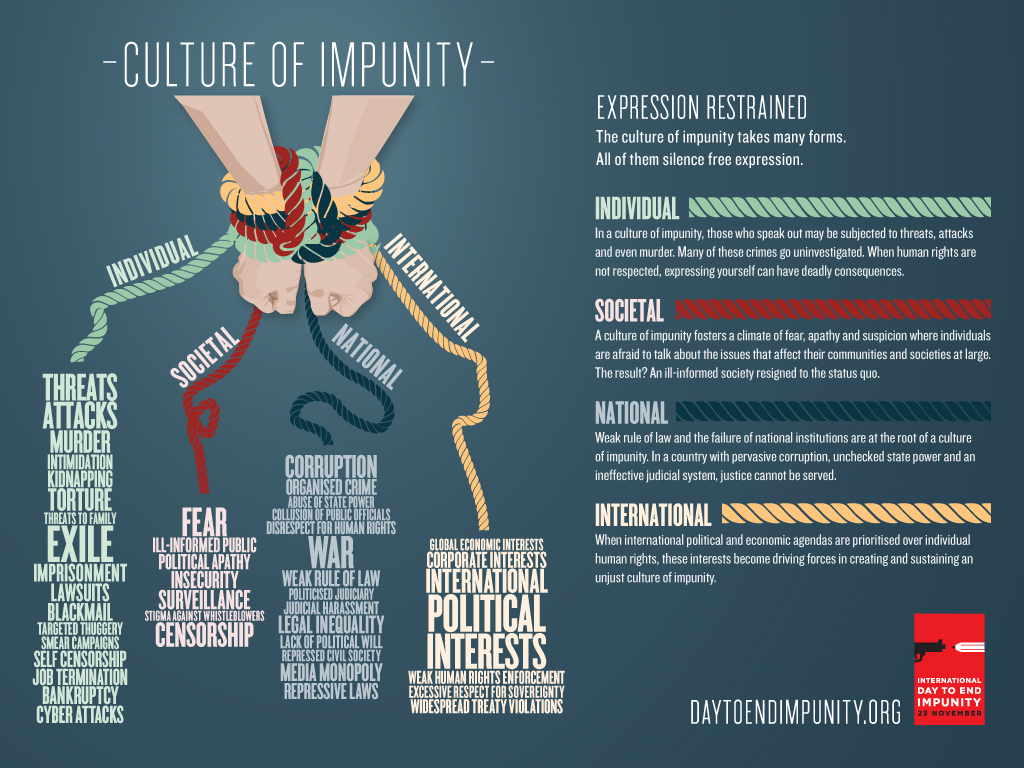

Impunity

Murder is a crime for which those involved should be punished. Yet in the case of the killing of journalists nine out of 10 killers go free. Put another way, in only five percent of cases for the murder of a journalist does the defendant receive a sentence of full justice. The most likely reason to kill a journalist is to silence them from speaking the truth to others.

IFEX, global freedom of expression network behind the International Day to End Impunity campaign said: “When someone acts with impunity, it means that their actions have no consequences. Intimidation, threats, attacks and murders go unpunished. In the past 10 years, more than 500 journalists have been killed. Murder is the ultimate form of censorship, and media are undoubtedly on the frontlines of free expression.”