21 Jan 2022 | Afghanistan, China, Kazakhstan, Opinion, Russia, Ruth's blog, United Kingdom, United States

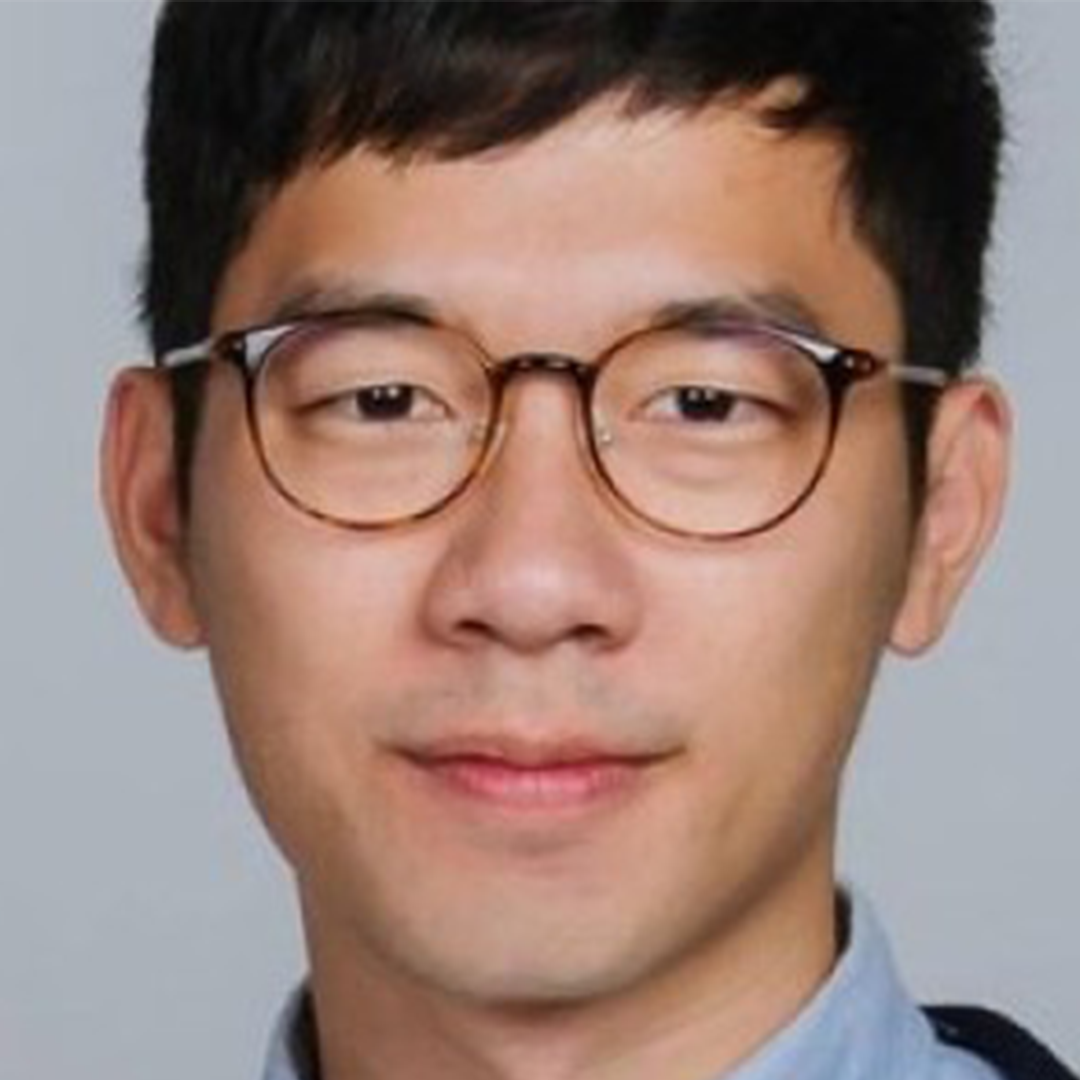

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson looks down at the podium during a media briefing in Downing Street. Photo: Justin Tallis/PA Wire/PA Images

It should surprise no-one that I am a political geek. I love politics. I love the cut and thrust of debate. I love the moments of high drama and the intrigue. Most of all I love the fact that genuine good can be done. That people’s lives can be made just a little easier by the power of our collective democracy.

So you’d assume that I would have relished the events of the UK Parliament this week. And I’d be lying if I didn’t admit to being completely obsessed with the minutiae of the debate around Partygate and the drama of the precarious position of the Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP as he seeks to survive the biggest political crisis of his premiership.

But I’m also angry. The British Government has been distracted for weeks, caught in a political crisis of their own making about whether or not the Prime Minister knowingly broke his own Covid-19 regulations. While the political establishment awaits a report from a senior civil servant to clarify what was, or wasn’t, happening behind the doors of Number 10, important issues are being sidelined or ignored and people are suffering.

This week the British Parliament held vital debates on the genocide of the Uighurs and the use of the British legal system to silence activists and journalists. Both debates passed broadly without comment or wider notice.

The Russian Federation is threatening the sovereign status of a democratic ally, Ukraine, on an hourly basis.

Biden has marked his first year in office.

52,581 people have died of Covid.

Protestors in Kazakhstan are being threatened with death if they continue to protest against the government, with 10,000 already arrested and 225 killed by the authorities.

23 million people in Afghanistan are experiencing extreme hunger as the Taliban starts attacking women activists.

These are some of the heartbreaking and terrifying realities which are happening around the world. These are the issues that should have dominated our news agenda this week, along with a cost of living crisis, a plan to deliver net zero and attacks on free expression around the world.

Index will continue to fight for these issues to be heard. For the voices of the persecuted to be recognised. While some of our leaders focus on domestic intrigue we’ll keep fighting for those that don’t have a voice.

17 Dec 2021 | Afghanistan, Magazine, Media Freedom, News and features, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021 Extras

As a woman and a journalist, I have been living my worst nightmare since 15 August 2021, the day the Afghan capital, Kabul, fell to the Taliban. Since that Sunday, I have been reporting about what women have lost – and what they continue to lose – as the new regime expands its power.

The Taliban have limited every aspect of women’s lives, from banning them from school and work to introducing long black uniforms that cover them from head to toe. Having grown up in Kabul since 2001, when the Taliban were deposed, I never imagined a return to the days when women were forced to stay home because of their gender.

When I was working as a journalist based in Kabul between 2011 and 2017, the media was the last hope for dissidents. Now the media, which continue to expose wrongdoing, have turned into dissidents. Today, making an editorial decision in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan is literally making a decision about life and death.

In our small newsroom at Rukhshana Media, an all-women news website, one recurrent concern is how to tell a story with minimum risk to the people involved. The journalist is often the first to face the consequences of his or her work.

Journalism under the Taliban

Afghanistan has never been a safe country for journalists but, after 2001, the nascent Afghan media were freer than media in neighbouring countries.

Now they can hardly function without getting visits and calls from the new rulers in charge – the group that labelled the media a military target and continued to threaten them before coming to power in mid-August.

Media outlets are closing and journalists are being arrested, tortured and being forced to go on the run.

On 14 August, the day before Kabul fell, Mujeeb Khalwatgar, executive director of the Afghan media advocacy group Nai, told me his organisation had heard from journalists in Baghlan, Kandahar and Herat provinces that the Taliban were searching for them.

The same day, I talked to a young journalist from the north-eastern province of Badakhshan who said his name was on the Taliban’s blacklist. He was hiding outside Fayzabad, the provincial capital.

Days before the Taliban took Fayzabad, one of his female colleagues was attacked by a man who covered his face. She survived the attack, but they were worried whether they could survive the new regime.

I talked to several women reporters from the provinces who sought shelter in Kabul as the Taliban took over, hoping to leave the country on evacuation flights. Many of them didn’t make it.

In early November, a 24-year-old-woman, one of only three female journalists in an entire province – who asked me not to name the province – said she was on a Taliban blacklist, according to a relative who was working with the militants. The radio station she worked for was among more than 150 media outlets forced to close because of Taliban-imposed restrictions and the economic crisis a month after Kabul fell.

As the breadwinner of a family of nine, the change in rulers meant she not only lost her job but is on the run for her life, simply for being a woman journalist. In the past two months, she has been forced to change her place of residence seven times to hide from the Taliban.

Women journalists are disappearing

An Afghan female journalist attends a Taliban news conference. Photo REUTERS/Jorge Silva

Two weeks after the Taliban’s return to power, Reporters Without Borders warned that “women journalists are in the process of disappearing from the capital”. The organisation noted that, of about 700 women journalists with jobs in Kabul, more than 600 had not returned to work. Some fled while others were forced to stay at home or go into hiding.

Our investigation at Rukhshana Media shows that there are no women journalists in radio or TV working in the western provinces of Herat, Farah, Badghis and Ghor.

The systematic removal of women from the media landscape is not the only immediate consequence of the Taliban’s return to power. Just three weeks after their takeover, the militants arrested 14 journalists, with at least nine of them subjected to violence during their detention, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Among those detained were an editor and four other journalists at Etilaat Roz, a newspaper that was a winner of Transparency International’s Anti-Corruption Award in 2020. Two of them were tortured by the Taliban and needed hospital treatment.

Today, journalists – both men and women – are still on the run. In November, I talked to a 31-year-old journalist who for the past eight years has been an investigative reporter for local print and online outlets. Since 15 August, he has been on the run with his family of four, having spent nights in five different places. He is particularly worried about his investigations into the Taliban-run religious schools.

“No one is listening to my calls for help, no one. I am just hoping the Taliban don’t catch me alive,” he said.

Reporters Without Borders and Human Rights Watch have issued warnings about the Taliban censorship of media, especially their “media regulations” which require journalists and media not to produce content “contrary to Islam” and not to report on “matters that have not been confirmed by officials”.

The chief editor of a radio station in Kabul who, despite not having a passport, attempted (unsuccessfully) to get on an evacuation flight out of the country in late August, told me his story. Now he is back at work, where, in one month, the Taliban have visited his office four times. Twice when his colleagues used the word “Taliban” instead of “the Islamic Emirate”, he received calls warning him to be careful with the choice of words.

He says his radio station, like all other Afghan media outlets, is under the Taliban’s scrutiny. Three of his colleagues in other provinces have been ordered by provincial officials to send their news first to the Taliban before it is signed off for broadcast.

With reliable sources of information having dried up and journalists either on the run or operating in an environment of fear, censorship and self-censorship, it is becoming harder to be a journalist.

The new environment creates opportunities for the circulation of false stories and propaganda on social media. Lately, it has become difficult to distinguish between real news and propaganda. Many on social media, including some journalists, are propagating stories that correspond with their biases and social and political prejudices which then will be used by some international media to verify their own assumptions and biases.

Fake news

Exposing false and misleading stories has been one of the primary goals of our team at Rukhshana Media, where we investigated two stories directly connected to misinformation and staged reporting in the past two months.

Many news outlets reported that Mahjabin Hakimi, a 25-year-old professional volleyball player, was beheaded by the Taliban. The reports were based entirely on the claim of her coach in Kabul’s volleyball club who spoke under a pseudonym. But our investigation, in which we interviewed five sources, including her parents and a friend who was present the day her body was found, showed that she died on 6 August – nine days before the Taliban took over Kabul.

In the second story, several people connected to the family of a nine-year-old girl featured in CNN’s bombshell report on child marriage told Rukhshana Media the report was invented.

Our reporters are working on the ground to bring women’s stories to the surface of a male-dominated Afghan media. In the past months, we have partnered with two international newsrooms, The Guardian and The Fuller Project, which has helped amplify the voice of Afghan women to wider audiences outside the country.

With women journalists remaining at risk, we are trying to create opportunities for them to continue their work and tell the stories of women in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, where they are banned from work and education and have no idea when they will be able to return to public life.

22 Oct 2021 | Afghanistan, News and features, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

Documenting the lives of women in Afghanistan, Forty Names by Afghan poet Parwana Fayyaz is a poignant reminder of lost opportunities, of freedoms given and then taken away, of a new generation living without enlightenment through education.

The collection, the title verse of which won the 2019 Forward Prize for Best Single Poem “focusses on stories and experiences from my childhood” and the ingrained attitude of acceptance that comes with a lack of schooling.

The title itself is reference to one of those very stories, where 40 women throw themselves off a cliff in order to protect their honour, rather than die with dishonour.

As she told Carcanet Press: “I grew up among women who told stories, stories concerning women. As the time passed, the women themselves became the stories. The majority of these women never went to school. They share their philosophy of life down through generations. [They say] “in the face of hardship, be patient, patience is the remedy”.”

Born in 1990, Fayyaz’s education challenges this idea. Now with a PhD in Persian Studies from Cambridge University, how can silence possibly make sense?

“When I left my home and Afghanistan to embark on my journey to become more educated, I began to reflect on the lives of the women I had always admired,” she said. “I began to question my admiration for them. They were suffering and yet they accepted it. To suffer in silence is seen as a token of patience.”

“With more education, patience became more elusive.”

Indeed, the choice now for so many women and girls in Afghanistan, sadly, is only silence and patience, but without the reward the piety is supposed to bring. As the Taliban tightens its stranglehold over the country, it forces out the oxygen required for art and literature to flourish and for women to learn how to express themselves in this sense.

Certainly, more than they previously should have done, everyday people in the west are taking notice of Afghanistan. The stories and images that have shocked so many people are not new, but it quite obviously takes a feeling of personal involvement – Nato troops were caught in a dangerous evacuation process – for people to take notice for long.

Even the process of translation for Fayyaz was important in this regard, “My poetry makes use of the art of translation to enhance the meaning of my story-poems for a Western audience, specifically involving the translation of Persian names into English. In active translation, the Persian names are the sounds and the English translations their echoes.”

Perhaps, to the English-speaking world, the plight of Afghans under the Taliban will remain as far-distant noises that will not reverberate so loudly for long. Forty Names, then, is in its truest sense a reflection of what has been lost for a whole generation of Afghan girls: a reminder that Afghanistan’s brief experience of democracy will never be forgotten.

Forty Names

by Parwana Fayyaz

I

Zib was young.

Her youth was all she cared for.

These mountains were her cots

the wind her wings, and those pebbles were her friends.

Their clay hut, a hut for all the eight women,

and her Father, a shepherd.

He knew every cave and all possible ponds.

He took her to herd with him,

as the youngest daughter

Zib marched with her father.

She learnt the ways to the caves and the ponds.

Young women gathered there for water, the young

girls with the bright dresses, their green

eyes were the muses.

Behind those mountains

she dug a deep hole,

storing a pile of pebbles.

II

The daffodils

never grew here before,

but what is this yellow sea up high on the hills?

A line of some blue wildflowers.

In a lane toward the pile of tumbleweeds

all the houses for the cicadas,

all your neighbors.

And the eagle roars in the distance,

have you met them yet?

The sky above, through the opaque skin of

your dust, carries whims from the mountains,

it brings me a story.

The story of forty young bodies.

III

A knock,

father opened the door.

There stood the fathers,

the mothers’ faces startled.

All the daughters standing behind them.

In the pit of dark night,

their yellow and turquoise colors

lining the sky.

‘Zibon, my daughter,

take them to the cave.’

She was handed a lantern;

she took the way.

Behind her a herd of colors flowing.

The night was slow,

the sound of their footsteps a solo music of a mystic.

Names:

Sediqa, Hakima, Roqia,

Firoza, Lilia, Soghra.

Shah Bakhat, Shah Dokht, Zamaroot,

Naznin, Gul Badan, Fatima, Fariba.

Sharifa, Marifa, Zinab, Fakhria, Shahparak, MahGol,

Latifa, Shukria, Khadija, Taj Begum, Kubra, Yaqoot,

Nadia, Zahra, Shima, Khadija, Farkhunda, Halima, Mahrokh, Nigina,

Maryam, Zarin, Zara, Zari, Zamin,

Zarina,

at last Zibon.

IV

No news. Neither drums nor flutes of

shepherds reached them, they

remained in the cave. Were

people gone?

Once in every night, an exhausting

tear dropped – heard from someone’s mouth,

a whim. A total silence again.

Zib calmed them.

Each daughter

crawled under her veil,

slowly the last throbs from the mill-house

also died.

No throbbing. No pond. No nights.

Silence became an exhausting noise.

V

Zib led the daughters to the mountains.

The view of the thrashing horses, the brown uniforms

all puzzled them. Imagined

the men snatching their skirts, they feared.

We will all meet in paradise,

with our honored faces

angels will greet us.

A wave of colors dived behind the mountains,

freedom was sought in their veils, their colors

flew with wind. Their bodies freed and slowly hit

the mountains. One by one, they rested. Women

figures covered the other side of the mountains.

Hairs tugged. Heads stilled. Their arms curved

beside their twisted legs.

These mountains became their cots.

The wind their wings, and those pebbles their friends.

Their rocky cave, a cave for all the forty women.

And their fathers and mothers disappeared.

Three Dolls

During the wars,

my mother made our clothes

and our toys.

For her three daughters,

she made dresses, and once

she made us each a doll.

Their figures were made with sticks

gathered from our neighbor’s garden.

She rolled white cotton fabric

around the stick frames

to create a skin for each doll.

Then she fattened the skin

with cotton extracted from an old pillow.

With black and red yarns bought from

uncle Farid’s store, my mother created faces.

A unique face for each doll.

Large black eyes, thick eyelashes and eyebrows.

Long black hair, a smudge of black for each nose.

And lips in red.

Our dolls came alive,

with each stitch of my mother’s sewing needle.

We dyed their cheeks with red rose-petals,

and fashioned skirts from bits of fabric,

from my mother’s sewing basket.

And finally, we named our dolls.

Mine with a skirt of royal green was the oldest and tallest,

and I called her Duur. Pearl.

Shabnam chose a skirt of bright yellow

and called her doll, Pari. Angel.

And our youngest sister, Gohar, chose deep blue fabric,

and named her doll, Raang. Color.

They lived longer than our childhoods.

Her Name is Flower Sap

Somewhere – in the no-man’s land,

there are high mountains, and there is a woman.

The mountains are seemingly unreachable.

The woman in her anonymity is untraceable.

The mountains are called the Tora Bora.

The woman is known as Sharbet Gula, Flower Sap.

In her faded-ruby-red Chador, she appeared

a young girl with a frown, with her green eyes.

Not knowing where to look.

When the world looked back at her.

As young kids, refugees of wartime in Pakistan

we were equally intrigued with her photograph.

‘Her eyes have the magic of good and bad.’

‘The light of her eyes can destroy fighter jets.’

So went Afghan children’s conversation

in the aftermath of 9/11. ‘But could she take down

The Taliban jets,’ we wondered,

as the jets crossed the skies in one song.

But Flower Sap could never answer us.

For she had disappeared like our childhood.

*

As the borders became damper lands,

Afghans like soft worms crawled toward their homeland.

In the in-between mountains,

Flower Sap re-appeared, without any answers.

Now she was a grown-up woman.

A mother of four girls. A widow.

There were some questions in her eyes.

The ones I had seen in my parents’ eyes.

Where do we go next? Now that our country is free.

She still did not have any answers.

And where was the power of her eyes?

I then saw her smiling. As an immigrant, I smiled too.

For her name saved the day.

She was taken to a hospital for her eyes.

The president of the county met her,

and sent her on a pilgrimage.

Her name educated her daughters,

it gave her a house and a reason to return to her homeland.

What else is there in the names and naming?

If not for reparation.

Forty Names was published in July 2021 by Carcanet Press, carcanet.co.uk