5 Jul 2019 | News and features, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“What is said and what is written is unbelievably important,” said Trevor Phillips, chairman of the board of Index on Censorship, at the close of the recent launch party for the Summer 2019 edition of Index Magazine.

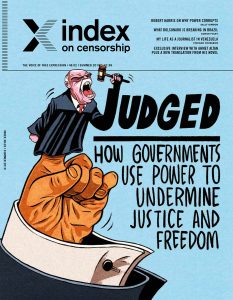

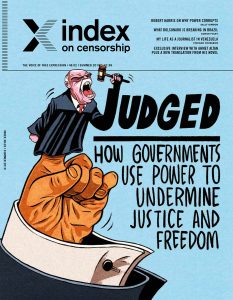

The summer 2019 edition, Judged: How Governments Use Power to Undermine Justice and Freedom, looks at attempts to undermine freedom of expression through attacks on the judiciary. The magazine covers issues ranging from new laws in Venezuela intended to limit freedom of the press to instances of self-censorship due to government control of content-sharing platforms in China to new technology created by journalists to check back against threats from politicians regarding the coverage of recent elections in South Africa.

Rachael Jolley, editor of Index magazine, explained that the idea behind the theme came from conversations she had with journalists in Italy covering areas with limited press freedom and hostile environments for journalists. She said, “one of the things that [the journalists] said kept them going was that there were still lawyers who were willing to stand up with them and defend them when they were attacked, when they had libel suits against them, when all the things that happen to them mean that they end up having to stand before a judge.”

This inspired Jolley to curate the latest edition of the magazine around legal issues, to address the legal fight for free speech behind the work of journalists to liberate the media under repressive regimes.

The keynote speaker of the evening was German writer Regula Venske, whose article What Does Weimar Mean to us 100 Years On? was published in the issue. Venske spoke about the history and ultimate downfall of the Weimar Republic, which is now known for fraught democracy and the promotion of freedom of expression, though Venske spoke about how attempts to preserve free speech in the republic were often complicated or insufficient. She walked the audience through some of the influential writing and art produced before the republic’s fall to Nazism.

To conclude, Venske quoted Weimar-era author and poet Erich Kästner: “You cannot fight the avalanche once it has developed into an avalanche, you have to crush the snowball.”

Venske added: “I think that is quite a good saying for the times we are now living in, though unfortunately, he did not leave a recipe for how one could prevent this. I think we need to keep on working for it.”

Phillips, the last speaker of the evening, lamented the state of media freedom in the multiple countries where right-wing leaders have recently come to power. He mentioned specifically the rise of Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, two countries covered in the summer issue. “My time at Index has been marked not by the incredible march of progress but actually a reminder, pretty much every week, why what this organisation does is so important,” he said.

He applied Kästner’s quote to the work Index on Censorship continues to do around the globe. Like Kästner, he explained, Index works to warn the people before the snowballs represented by the arrest of a journalist or the censorship of an artwork become an avalanche of fascism.

“The avalanche starts long before you hear it,” Phillips concluded. “A large part of what we do is give the avalanche warning.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”107175″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”107175″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jun 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Xinran, Ahmet Altan, Stephen Woodman, Karoline Kan, Conor Foley, Robert Harris, Stefano Pozzebon and Melanio Escobar”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Judged: How governments use power to undermine justice and freedom. The summer 2019 edition of Index on Censorship magazine

The summer 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at the narrowing gap between a nation’s leader and its judges and lawyers. What happens when the independence of the justice system is gone and lawyers are no longer willing to stand up with journalists and activists to fight for freedom of expression?

In this issue Stephen Woodman reports from Mexico about its new government’s promise to start rebuilding the pillars of democracy; Sally Gimson speaks to best-selling novelist Robert Harris to discuss why democracy and freedom of expression must continue to prevail; Conor Foley investigates the macho politics of President Jair Bolsonaro and how he’s using the judicial system for political ends; Jan Fox examines the impact of President Trump on US institutions; and Viktória Serdült digs into why the media and justice system in Hungary are facing increasing pressure from the government. In the rest of the magazine a short story from award-winning author Claudia Pineiro; Xinran reflects on China’s controversial social credit rating system; actor Neil Pearson speaks out against theatre censorship; and an interview with the imprisoned best-selling Turkish author Ahmet Altan.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Judged: How governments use power to undermine justice and freedom”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Law and the new world order by Rachael Jolley on why the independence of the justice system is in play globally, and why it must be protected

Turkey’s rule of one by Kaya Genc President Erdogan’s government is challenging the result of Istanbul’s mayoral elections. This could test further whether separation of powers exists

England, my England (and the Romans) by Sally Gimson Best-selling novelist Robert Harris on how democracy and freedom of expression are about a lot more than one person, one vote

“It’s not me, it’s the people” by Stephen Woodman Mexico’s new government promised to start rebuilding the pillars of democracy, but old habits die hard. Has anything changed?

When political debate becomes nasty, brutish and short by Jan Fox President Donald Trump has been trampling over democratic norms in the USA. How are US institutions holding up?

The party is the law by Karoline Kan In China, hundreds of human rights lawyers have been detained over the past years, leaving government critics exposed

Balls in the air by Conor Foley The macho politics of Brazil’s new president plus ex-president Dilma Rousseff’s thoughts on constitutional problems

Power and Glory by Silvia Nortes The Catholic church still wields enormous power in Spain despite the population becoming more secular

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson In Freedonia

What next for Viktor Orbán’s Hungary? Viktoria Serdult looks at what happens now that Hungary’s prime minister is pressurising the judiciary, press, parliament and electoral system

When justice goes rogue by Melanio Escobar and Stefano Pozzebon Venezuela is the worst country in the world for abuse of judicial power. With the economy in freefall, journalists struggle to bear witness

“If you can keep your head, when all about you are losing theirs…” by Caroline Muscat It’s lonely and dangerous running an independent news website in Malta, but some lawyers are still willing to stand up to help

Failing to face up to the past by Ryan McChrystal argues that belief in Northern Ireland’s institutions is low, in part because details of its history are still secret

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]Small victories do count by Jodie Ginsberg The kind of individual support Index gives people living under oppressive regimes is a vital step towards wider change[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Sending out a message in a bottle by Rachael Jolley Actor Neil Pearson, who shot to international fame as the sexist boss in the Bridget Jones’ films, talks about book banning and how the fight against theatre censorship still goes on

Remnants of war by Zehra Dogan Photographs from the 2019 Freedom of Expression Arts Award fellow Zehra Doğan’s installation at Tate Modern in London

Six ways to remember Weimar by Regula Venske The name of this small town has mythic resonances for Germans. It was the home of many of the country’s greatest classical writers and gave its name to the Weimar Republic, which was founded 100 years ago

“Media attacks are highest since 1989” by Natasha Joseph Politicians in South Africa were issuing threats to journalists in the run-up to the recent elections. Now editors have built a tracking tool to fight back

Big Brother’s regional ripple effect by Kirsten Han Singapore’s recent “fake news” law which gives ministers the right to ban content they do not like, may encourage other regimes in south-east Asia to follow suit

Who guards the writers? Irene Caselli reports on journalists who write about the Mafia and extremist movements in Italy need round-the-clock protection. They are worried Italy’s deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini will take their protection away

China in their hands by Xinran The social credit system in China risks creating an all-controlling society where young people will, like generations before them, live in fear

Playing out injustice by Lewis Jennings Ugandan songwriter and politician Bobi Wine talks about how his lyrics have inspired young people to stand up against injustice and how the government has tried to silence him[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]“Watch out we’re going to disappear you” by Claudia Pineiro The horrors of DIY abortion in a country where it is still not legal are laid bare in this story from Argentina, translated into English for the first time

“Knowing that they are there, helps me keep smiling in my cell” by Ahmet Altan The best-selling Turkish author and journalist gives us a poignant interview from prison and we publish an extract from his 2005 novel The Longest Night

A rebel writer by Eman Abdelrahim An exclusive extract from a short story by a new Egyptian writer. The story deals with difficult themes of mental illness set against the violence taking place during the uprising in Cairo’s Tahrir Square[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]Index around the world – Speak out, shut out by Lewis Jennings Index welcomed four new fellows to our 2019 programme. We were also out and about advocating for free expression around the world[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Music has long been a form of popular rebellion, especially in the 21st century. These songs, provide a theme tune to the new magazine and give insight into everything from the nationalism in Viktor Orban’s Hungary to the role of government-controlled social media in China to poverty in Venezuela

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Music has long been a form of popular rebellion, especially in the 21st century. These songs, provide a theme tune to the new magazine and give insight into everything from the nationalism in Viktor Orban’s Hungary to the role of government-controlled social media in China to poverty in Venezuela

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Feb 2018 | Guest Post, News and features, Turkey

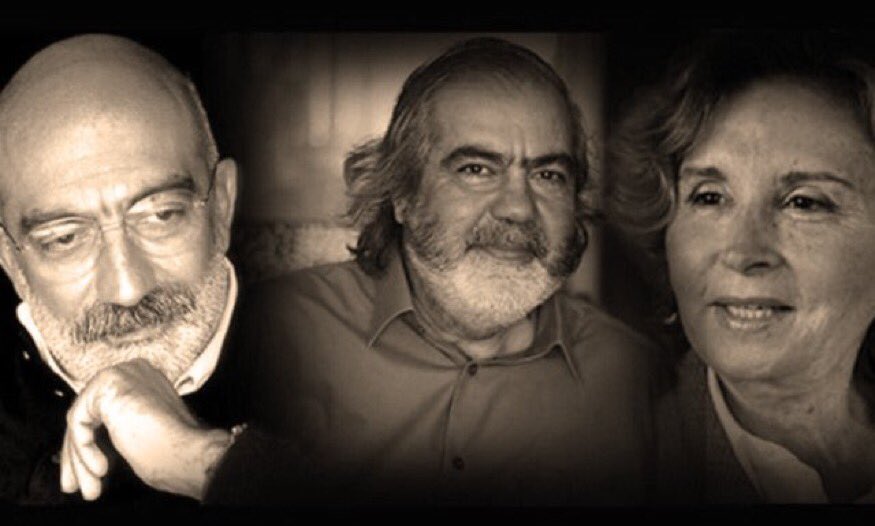

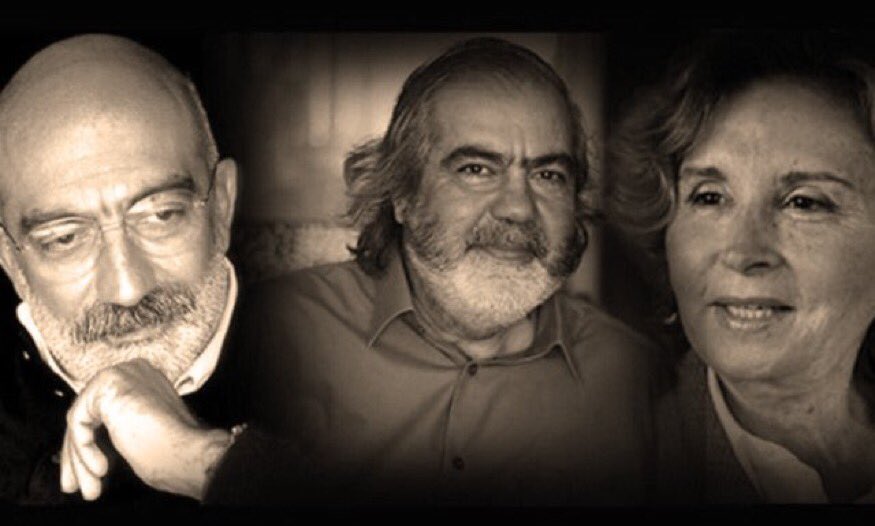

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91904″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Two of Turkey’s most prominent writers, brothers Ahmet and Mehmet Altan, were sentenced to life in prison on Friday 16 February 2018.

Convicted on groundless charges related to the attempted coup in 2016 against the government led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, these verdicts, the first of their kind, set a devastating precedent for the many other journalists and writers in Turkey who are being tried on similarly spurious charges widely believed to be politically motivated to silence all criticism of Erdoğan.

Since they began last July, I have been present to observe the Altans’ trial and to witness extraordinary violations of due process and the defendants’ rights to a fair trial. They are also emblematic of an unprecedented crackdown on critical voices in a country where the rule of law is in free fall.

The brothers were arrested in the aftermath of the coup attempt under a state of emergency imposed by Erdogan in July 2016 and renewed six times since, which gave him sweeping powers and pushed Turkey closer to authoritarianism. It is hard to overstate the extent of the purge that has taken place: 200 journalists and 50,000 individuals have been arrested. Independent mainstream media have been all but silenced, with over 180 media outlets and publishing houses closed down. Over 150,000 civil servants, journalists and academics, have been summarily dismissed with no effective appeals process or prospect of re-employment. Dozens of the dismissed have committed suicide.

Once arrested, the Altans found themselves in a legal system where the rule of law has been dismantled with terrifying speed since the coup attempt. What judicial independence existed previously was eviscerated as 4,200 judges and prosecutors were summarily dismissed and replaced with political appointees. The legal system itself – parts of which have long been used to judicially harass independent voices – has been transformed wholescale into a system of repression, with the judiciary now playing a central role in the deterioration of free speech and the rule of law itself.

The indictment in the Altans’ case is 247 pages long, and was largely copied and pasted from other indictments, evidenced by a name from another trial mistakenly appearing in the document. The brothers initially faced three consecutive life terms on charges of plotting to overthrow the government, parliament and the constitutional order for their alleged links to a network led by Fethullah Gülen whom the government accuses of orchestrating the attempted coup. These charges were subsequently reduced to just the latter, carrying one ‘aggravated’ life sentence: a sentence without prospect of parole. Like scores of other journalists across the country, the Altans are also accused of supporting multiple additional terrorist groups – groups which are themselves even in conflict with one another.

Throughout the trials there has been scant evidence or detail of the criminal acts the Altans are said to have committed. A key part of the case has centred on their participation in a TV programme on 14 July 2016, the day before the coup attempt, during which they are said to have sent “subliminal messages” to the coup plotters. (In fact, they discussed the fact that there would be elections and that Erdogan might be voted out.) After this “evidence” was ridiculed wholesale in the Turkish media, it was dropped. In a similarly farcical use of evidence, six $1 bills found in Mehmet Altan’s apartment are cited as proof of his support for the coup, though how these could possibly contribute to attempting to overthrowing the constitutional order remains unclear.

Leading QC, Pete Weatherby, characterised the proceedings as a “show trial” in a report for English Bar Human Rights Committee. At a hearing in November 2017, the judge abruptly expelled the entire defence team. Mehmet Altan was left to defend himself with no lawyer present. I had the surreal experience of observing that hearing with his defence team from the court cafeteria via Twitter. On Monday of this week, his lawyer was expelled from court once again, this time for insisting that the recent landmark Turkish Constitutional Court decision on his client’s case be included in the court’s record, to say nothing of it being upheld.

The lower court’s decision to defy this constitutional court decision on Mehmet Altan is itself at the heart of a constitutional crisis unfolding in Turkey. Until 11 January 2018, the constitutional court had exempted itself from deciding any State of Emergency related cases, despite the 100,000 applications pending before it. Then in a landmark decision a month ago, the constitutional court ruled 11-6 that the detention of Mehmet Altan and veteran journalist, Sahin Alpay for over a year constituted violations of their constitutionally protected “right to personal liberty and security” and “freedom of expression and the press”, establishing the way for their immediate release and setting the necessary precedent for the releases of the dozens of other jailed journalists.

In the hours following the decision, however, a criminal court in Istanbul defied the constitutional court ruling declaring the judgement was a “usurpation of authority” and therefore could not be accepted. This language was disturbingly similar to the reaction of the deputy prime minister and government spokesperson, Bekir Bozdağ, who had tweeted this objection to the decision, claiming that the Constitutional Court had “exceeded” its authority.

This political interference was blatantly in violation of the Turkish Constitution, which renders all constitutional court decisions binding on lower courts. The ongoing crisis surrounding the rule of law and separation of powers, which has been growing since the imposition of the state of emergency, has reached its nadir with Friday’s verdict against Mehmet Altan, demonstrating that Turkey’s citizens can have no expectation of an independent or effective legal remedy in their country.

This crisis in Turkey has profound implications for the European human rights system. The Altans’ case, along with those of eight others relating to journalism is pending before the European Court of Human Rights, of which Turkey has been a member since 1954. Their lawyers applied to the European court in November 2016 after continued inaction by the Turkish Constitutional Court and in April 2017, the court accorded priority status to the cases, opening the way for accelerated proceedings. So important are the implications of these cases for freedom of expression in the country as a whole that an unprecedented group intervened before the court including the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and a coalition of international human rights NGOs led by PEN International.

Since those interventions, however, the European court has been silent. As there is no expectation of independent or effective justice in Turkey, Strasbourg is the last hope for justice for the writers – and indeed, for Turkish society as a whole. And there can be no more urgent cases than these for the European court: they concern individuals who have been detained for over eighteen months, solely on the basis of their writing, that is to say for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression and opinion, which is guaranteed under the European Convention of Human Rights, of which the court is guardian.

However, many in Turkey fear that politicking at the highest levels between Turkey and European member states and institutions is delaying this judgement. Indeed it is widely felt that Europe’s relative silence on the journalists cases is provoked by more utilitarian concerns: the EU-Turkey refugee deal for one, military interests in Syria for another. Meanwhile, Theresa May has shown she is more concerned about selling Erdogan fighter jets and securing a post-Brexit free trade agreement than promoting democracy or human rights.

Meanwhile, the European Union and May appear to be sacrificing the very people who have fought for democratic and liberal values in Turkey. One of the great privileges of my time observing these cases over the last 18 months has been to witness historic defences of freedom of expression from journalists in the dock, on trial for their lives for daring to criticise authoritarianism, corruption and human rights abuses. I think of Ahmet Altan’s defiant closing statement to the judge in the prison court this Tuesday, surrounded by 30 heavily armed riot police – “I came here not to be judged but to judge. I will judge those who, in cold blood, killed the judiciary in order to incarcerate thousands of innocent people.”

Europe would do well to take a longer-term view, to uphold the values of democracy and human rights lest we lose Turkey outright to authoritarianism. Political pressure does work: On the same day as the Altans were sentenced, the Turkish-German journalist, Deniz Yucel, was released after a year in detention following talks between German Chancellor Merkel and Turkish PM Yildirim. Political pressure from Germany is also widely credited for the release of ten human rights defenders and Amnesty International staff in October 2017. Much more of this pressure is needed. Other countries like the UK, and political and financial institutions including the EU need to step up and demonstrate the values they profess to hold in their relations with Turkey.

We urge Europe not to abandon the Altans and Turkey’s other jailed journalists. We can only hope for Turkey’s democrats that justice does not come too late. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”3″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1519806559338-3ec987ef-0828-8″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Feb 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan and Nazli Ilcak

Index on Censorship strongly condemns Turkey’s sentencing of six defendants — including journalists Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan and Nazli Ilcak — to aggravated life sentences.

“Today’s appalling verdict represents a new low for press freedom in Turkey and sheds light on how the courts might approach other cases concerning the right to freedom of expression. Today we stand in solidarity with all imprisoned journalists and continue to call on the government to drop all charges,” Hannah Machlin, project manager, Mapping Media Freedom, said.

On 16 February 2018, the 26th High Criminal Court of Istanbul sentenced the defendants to life in prison over allegations related to the attempted July 2016 coup, which Turkish authorities claim was orchestrated by Fettulah Gulen. The charges were detailed in a 247-page long indictment which identifies President Erdogan and the Turkish government as the victims. The defendants were accused of attempting to disrupt constitutional order and inserting subliminal messages into broadcasts.

Ahmet Altan is a novelist, journalist and former editor in chief of the shuttered Taraf daily. His brother, Mehmet Altan is a columnist and professor. Nazli Ilcak is a journalist, writer and former party deputy. The other defendants were Fevzi Yazıcı, who was head of visual at Zaman; Yakup Simşek, who worked in Zaman’s advertising department; Sükrü Tuğrul Ozşengül, a retired police academy teacher who was accused on the basis of a tweet where he predicted there would be a coup.

Today marked the fifth and final hearing in the case which is widely seen as politically motivated.

This is the first conviction of journalists in trials related to the attempted coup.

All three have been detained since 2016 and have denied all charges, citing lack of evidence.

On 19 September 2017 Ahmet Altan testified from Silivri Prison.

“This is a case in which the absurdity of the allegation overwhelms even the gravity of the charges.”

Earlier today, Deniz Yucel, a German-Turkish journalist, was released and indicted on charges related to the hacking of the Turkish Energy Minister’s email account . He spent 366 days in prison, including in solitary confinement. Yucel could face up to 18 years in prison.

Turkey is currently the largest jailer of journalists in the world with 153 media workers still behind bars in Turkey.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”2″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1518794983391-6bd72ea1-eea5-5″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”107175″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”107175″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.