Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

On Tuesday, the UK learned that radical cleric Anjem Choudary had been convicted under Section 12 of the UK’s 2000 Terrorism Act, which makes it a crime to invite “support for a proscribed organisation”. Choudary had long argued that, in advocating his support for the creation of an Islamic state and the imposition of sharia law, he was simply exercising his right to free speech. And this was true. Like any other citizen, Choudary should be allowed to express his political views, no matter how vile or abhorrent.

But there is also no doubt that Choudary trod a very careful and deliberate line. Choudary understands that in a free and democratic society (the kind to which Choudary would like to see a violent end), the only occasions on which free speech should be curtailed is when the speech provokes – or presents a clear and imminent danger of provoking – violence. Beyond that line, no one, including Choudary, should be prevented from expressing their view.

|

If free speech is to mean anything, then free speech rights must apply equally.

|

The immediate question, then, is whether Choudary was advocating violence? In Index’s view, he was. Choudary was convicted of encouraging followers to join IS, a proscribed terrorist organisation. Although he did not directly incite violence, he was calling on others to join a group whose avowed aims are victory through violence. In this context, the definition of a proscribed group becomes crucial. Proscribed groups should only be ones that directly use and incite violence, not simply political parties whose views do not chime with those of the government or even the majority of the population. This is a vital line.

If free speech is to mean anything, then free speech rights must apply equally: as much to those whose views we abhor as to those whom we support. Choudary deliberately exploited liberal values to advocate wholly illiberal ones. So it is critical that in responding to the likes of Choudary that we do not respond by shifting further towards the kind of illiberal society he favours. The laws which (should) protect Choudary’s right to envisage the imposition of an Islamic state are the same that protect the rights of the rest of us to voice our opposition: the best way to dispute views you disagree with is openly, rather than driving them underground where they can grow.

Index is concerned at the current direction of travel in anti-extremism law and its damaging implications for free speech. New leglisation is currently under consideration that would target those who advocate extremist views but do not directly encourage violence. This could include banning orders that would prevent non-violent extremists from speaking or publishing – a move that risks undermining the democratic judicial process, as David Anderson, the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation told BBC’s Today programme.

This is a dangerous road to go down. The definition of terrorism is already contentious and further defining ‘non-violent’ extremism almost impossible. Indeed, Christian groups have already expressed concern that the proposed new law would, for example, prevent an opponent of gay marriage from expressing such a view. Nor should we use the examples of Choudary’s use of social media to greenlight enforcing social media companies to act as arms of the law, making decisions about content removal that should be made by courts.

Across the world, Index defends the rights of those who express views their government deems ‘extremist’. Choudary is an extremist. His views are repugnant and to be countered at every opportunity, but he should be allowed to express them.

More information about UK law and counter terrorism

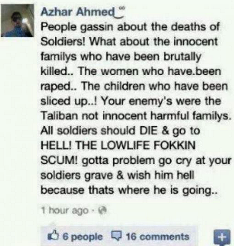

Yorkshire 19-year-old Azhar Ahmed is facing charges of “racially aggravated public order offences” after he posted an angry Facebook status update about the reporting of the latest British Army fatalities in Afghanistan.

Ahmed’s sentiment (see pic) was not unsual. He starts off with the widely repeated complaint that deaths of British soldiers are given blanket coverage, while deaths of Afghans barely merit a mention. This is true, and hardly controversial.

Ahmed’s mistake, apparently, is to continue to vent his anger, and suggests that British soldiers should all die and go to hell. Strong language, but does it tip into incitement to violence? I think not. Nor, for that matter, do West Yorkshire police, who have not pursued Ahmed on this charge. Rather, they have sinisterly construed Ahmed’s comment as “racially aggravated”.

Serving British army soldiers do not count as an ethnicity. So why angry words about them could be seen as racially aggravated is a mystery. But perhaps unwittingly, those responsible for this charge have revealed something dark about the way the war in Afghanistan is now viewed.

Unconditional support for soldiers is now expected, even as we become increasingly unsure of what they’re doing out there. From the most ardent supporter of the war to the most strident critic, everyone claims to be acting in the interest of Our Brave Boys. This is now not a matter of politics, but loyalty. This question is compounded in Ahmed’s case, as the six soldiers killed were all from the local Yorkshire Regiment. Ahmed’s home town Dewsbury was also home of Britain’s best-known suicide bomber, Mohammad Sidique Khan, in the months before his attack on London. Suspicion of young Muslims voicing anti-troops opinions in the area is predictable.

But still the “racially aggravated” charge doesn’t stick, unless one is willing to buy into the notion that Afghanistan is part of an ethno-religious war between “Islam” and “the West”. This is the line that the likes of Anjem Choudary have been pushing for years. And now it seems West Yorkshire police agree.

The Home Secretary’s decision to ban an extremist group shows exactly why we must not allow sentiment to overrule free speech says Padraig Reidy

The Home Secretary’s decision to ban an extremist group shows exactly why we must not allow sentiment to overrule free speech says Padraig Reidy

(more…)

Oliver Kamm responds to my post on Anjem Choudary’s proposed march through Wootton Bassett, where I asked if previous attempts to stop provocative processions, such as Oswald Mosley’s attempt to march through Cable Street, were wrong:

Yes, those who tried to stop the British Union of Fascists from marching in the East End in October 1936 were wrong. The BUF had a democratic right to march in peacetime, and the attempt to stop them did them a power of good. Mosley was looking for a way to call it off anyway, so that he could get to Berlin and secretly marry Diana Mitford Guinness in Goebbels’s drawing room (which he managed to do two days later). Support for Mosley in the East End increased after the Battle of Cable Street, as did antisemitic violence. Thugs attacked Jews and their properties, in the so-called Pogrom of Mile End, a week later.

In the end, despite an appalling failure among leaders of the main parties in the 1930s (Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain, Herbert Samuel and the ineffably foolish George Lansbury) to recognise the threat from the dictators, it was democratic politics that defeated Mosley and secured economic recovery, not opposition on the streets. When he was interned in 1940, Mosley was a permanently discredited figure.

Read the full post here