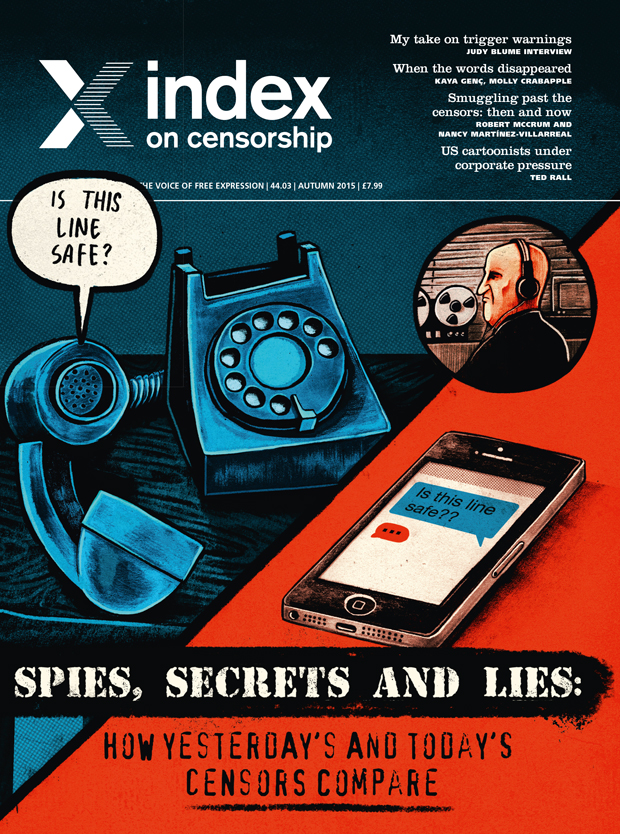

9 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

Post-Soviet Union, after the fall of the Berlin wall, after the Bosnian war of the 1990s, and after South Africa’s apartheid, the world’s mood was positive. Censorship was out, and freedom was in.

But in the world of the new censors, governments continue to try to keep their critics in check, applying pressure in all its varied forms. Threatening, cajoling and propaganda are on one side of the corridor, while spying and censorship are on the other side at the Ministry of Silence. Old tactics, new techniques.

While advances in technology – the arrival and growth of email, the wider spread of the web, and access to computers – have aided individuals trying to avoid censorship, they have also offered more power to the authorities.

There are some clear examples to suggest that governments are making sure technology is on their side. The Chinese government has just introduced a new national security law to aid closer control of internet use. Virtual private networks have been used by citizens for years as tunnels through the Chinese government’s Great Firewall for years. So it is no wonder that China wanted to close them down, to keep information under control. In the last few months more people in China are finding their VPN is not working.

Meanwhile in South Korea, new legislation means telecommunication companies are forced to put software inside teenagers’ mobile phones to monitor and restrict their access to the internet.

Both these examples suggest that technological advances are giving all the winning censorship cards to the overlords.

But it is not as clear cut as that. People continually find new ways of tunnelling through firewalls, and getting messages out and in. As new apps are designed, other opportunities arise. For example, Telegram is an app, that allows the user to put a timer on each message, after which it detonates and disappears. New auto-encrypted email services, such as Mailpile, look set to take off. Now geeks among you may argue that they’ll be a record somewhere, but each advance is a way of making it more difficult to be intercepted. With more than six billion people now using mobile phones around the world, it should be easier than ever before to get the word out in some form, in some way.

When Writers and Scholars International, the parent group to Index, was formed in 1972, its founding committee wrote that it was paradoxical that “attempts to nullify the artist’s vision and to thwart the communication of ideas, appear to increase proportionally with the improvement in the media of communication”.

And so it continues.

When we cast our eyes back to the Soviet Union, when suppression of freedom was part of government normality, we see how it drove its vicious idealism through using subversion acts, sedition acts, and allegations of anti-patriotism, backed up with imprisonment, hard labour, internal deportation and enforced poverty. One of those thousands who suffered was the satirical writer Mikhail Zoshchenko, who was a Russian WWI hero who was later denounced in the Zhdanov decree of 1946. This condemned all artists whose work didn’t slavishly follow government lines. We publish a poetic tribute to Zoshchenko written by Lev Ozerov in this issue. The poem echoes some of the issues faced by writers in Russia today.

And so to Azerbaijan in 2015, a member of the Council of Europe (a body described by one of its founders as “the conscience of Europe”), where writers, artists, thinkers and campaigners are being imprisoned for having the temerity to advocate more freedom, or to articulate ideas that are different from those of their government. And where does Russia sit now? Journalists Helen Womack and Andrei Aliaksandrau write in this issue of new propaganda techniques and their fears that society no longer wants “true” journalism.

Plus ça change

When you compare one period with another, you find it is not as simple as it was bad then, or it is worse now. Methods are different, but the intention is the same. Both old censors and new censors operate in the hope that they can bring more silence. In Soviet times there was a bureau that gave newspapers a stamp of approval. Now in Russia journalists report that self-censorship is one of the greatest threats to the free flow of ideas and information. Others say the public’s appetite for investigative journalism that challenges the authorities has disappeared. Meanwhile Vladimir Putin’s government has introduced bills banning “propaganda” of homosexuality and promoting “extremism” or “harm to children”, which can be applied far and wide to censor articles or art that the government doesn’t like. So far, so familiar.

Censorship and threats to freedom of expression still come in many forms as they did in 1972. Murder and physical violence, as with the killings of bloggers in Bangladesh, tries to frighten other writers, scholars, artists and thinkers into silence, or exile. Imprisonment (for example, the six year and three month sentence of democracy campaigner Rasul Jafarov in Azerbaijan) attempts to enforces silence too. Instilling fear by breaking into individuals’ computers and tracking their movement (as one African writer reports to Index) leaves a frightening signal that the government knows what you do and who you speak with.

Also in this issue, veteran journalist Andrew Graham-Yool looks back at Argentina’s dictatorship of four decades ago, he argues that vicious attacks on journalists’ reputations are becoming more widespread and he identifies numerous threats on the horizon, from corporate control of journalistic stories to the power of the president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, to identify journalists as enemies of the state.

Old censors and new censors have more in common than might divide them. Their intentions are the same, they just choose different weapons. Comparisons should make it clear, it remains ever vital to be vigilant for attacks on free expression, because they come from all angles.

Despite this, there is hope. In this issue of the magazine Jamie Bartlett writes of his optimism that when governments push their powers too far, the public pushes back hard, and gains ground once more. Another of our writers Jason DaPonte identifies innovators whose aim is to improve freedom of expression, bringing open-access software and encryption tools to the global public.

Don’t miss our excellent new creative writing, published for the first time in English, including Russian poetry, an extract of a Brazilian play, and a short story from Turkey.

As always the magazine brings you brilliant new writers and writing from around the world. Read on.

© Rachael Jolley

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.

14 Jul 2014 | Africa, Magazine, News, South Africa

Index on Censorship remembers Nadine Gordimer, who died today at 90. The South African author, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature and the Booker Prize among many other honours, was a long-time Index supporter and patron. She wrote for Index on Censorship magazine a number of times, including in its first year. Gordimer was also involved in the anti-apartheid movement, and much of her work deals with issues of politics and race. Three of her books – Burger’s Daughter, A World of Strangers, The Late Bourgeois World – were banned by the apartheid regime.

Ursula Owen was editor of Index magazine in 1994, when South Africa held its first free election. An issue of the magazine celebrated the historic event with an article by Gordimer, among others.

Owen said: “I remember visiting her in the late 90s, together with Adewale Maya Pearce, when I was running Index. We sat in her garden in Johannesburg. She was attentive and full of energy, and talked with great passion about what was going on in post-apartheid South Africa. Later we went to supper with Helen Suzman – an extraordinary experience to spend time in the same room with these two remarkable women. Awesome, as my granddaughters would say.”

Jayne Whiffin, publisher of Index magazine, said: “I am very sad to hear of Nadine Gordimer’s passing today. Nobody growing up in South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s could be unfamiliar with her work, and her short story, Message in a Bottle has great personal significance for me as the first piece of writing I encountered of hers while at school in South Africa. Her writing was an exemplar of how fiction can tell the truth even under the most strenuous forms of oppression, and she will be sorely missed both in South Africa and around the world.”

In celebration of her remarkable life, Index has created a collection of Gordimer’s articles that appeared in the magazine. These are free to read until 14 September.

Apartheid and censorship [1972]

Standing in the queue [1994]

Act two: one year later [1995]

Rushdie revisited [2008]

This article was posted on July 14, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Dec 2013 | News, South Africa

Oliver Tambo (Image: Rob C. Croes / Anefo / Wikimedia Commons)

In May 1986 Oliver Tambo, then president of the African National Congress, was interviewed by former Index on Censorship magazine editor Andrew Graham-Yooll in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The following are extracts from the conversation.

—

Are you planning for a time after apartheid?

Oliver Tambo: That should not pose a problem. We do not find it necessary as yet to have people assigned to specific roles in the new South Africa. I don’t think we should have any problem deciding who should do what. For the moment the priority is to concentrate on ending the system. We say we want a government that derives its mandate from the people of South Africa as a whole, a majority government. If we had to pick a cabinet we would do that without any difficulty.

We have never ever doubted that apartheid will crumble some day. Now, we are able to say some day soon. We have never had any doubt about this. We know that we will be in Pretoria soon – if we choose Pretoria to be the seat of government. But it is so notorious as the seat of apartheid that the people who will be in power (not necessarily Oliver Tambo) might want to go elsewhere. But there will be a government of the people in South Africa and we will all get there some day soon. We have never doubted this. Some day soon, is how we look at it. ‘Soon’ can be stretched. We labour under no illusions that apartheid will not fall without heavy sacrifices possibly even after a protracted and vicious confrontation. We are prepared for that but at the end of the day we know apartheid must end.

Is there a real possibility of a peaceful transition to majority government?

One hopes it will not be too violent, but we must be prepared for the reality.

Pressures have got to be external and serious up to the point where we are able to say apartheid has been destroyed and a new South Africa is emerging. But if we should withhold pressure, even withdraw it, then apartheid continues. It is only since 1985 that international pressure has begun to measure up to the demands of the situation, encouraged significantly by the rising pressures from within the country. These two have resulted in a new thinking on the part of those who are administering the apartheid system.

You have compared 19th century colonialism and racism and 20th century imperialism and apartheid.

The point was that at the heart of apartheid was racism. Apartheid is the strongest concentration of racist concepts put into action. But that did not start with apartheid, it was there before. It found expression in colonial practice. In fact, one can say that in South Africa racism started with the first settlers. It was with the Dutch before 1805. Well. I should not say the first because it was a later development.

When Dutch settlers got there they found indigenous people. There was no racism at that point, they were just different people. Subsequently, laws were introduced which enforced separation. Then the British came. Their most racist act was the constitution, which incorporates racist clauses. From there racism developed roots. Racists were encouraged and in the end they had a racist government in power. But they were built on the constitution adopted by a British government and so you have this monster of apartheid.

But the point is that what we see today has been there before. Perhaps the true process of reversal can only start in South Africa where it has reached its worst. If you can succeed in uprooting this thing in South Africa, I think that the fate will be to eliminate racist practices everywhere. Especially if we do succeed, as we are hoping, in creating a new relationship between people, learning from the horrors of the apartheid system. Just as we hoped that people who worked against Nazism would not want to entertain anything like it again. Those who have experienced the worst excesses of racism should want to get away from that totally. They should have a completely non-racial system of a kind which should be attractive internationally.

If only people could live together, innocent of colour, skin colour, of racial difference… South Africa therefore may well be the starting point of this end to racism which has been with us in the world for centuries.

How do you see the predicament of South Africa’s neighbours?

It is a predicament. They have been put in that situation by history. They found themselves in that position before independence. There was nothing wrong with that. South Africa was the heart of their economies and they were linked to South Africa. If you did not have the apartheid system, or if the transition to democratic rule in southern Africa had taken place at the same time as it did in these other territories we would have had no problem at all. But they became politically independent first and are therefore quite naturally opposed to the colonial system in South Africa. They were themselves involved in colonial struggles. They have achieved their objective of winning political power at least, we have not. So they support us.

But there is more to it than that. The apartheid system is inhuman to its victims and makes fools of them. So the neighbouring states want to see it ended. They do what they can, they recognise the reality of the situation. They do care, they cannot fight. They can only defend themselves if they are attacked. But even then it would not take too long before they were overwhelmed. They cannot impose sanctions because of their tremendous dependence on South Africa. But they do the next best thing, that is to organise themselves into a collective, SADCC, which seeks to reduce that dependence. That is the next best thing. They are neighbours, so they are liable to be harassed and destabilised. The South Africans can impose sanctions against them, they impose sanctions against Mozambique, they have imposed sanctions against Lesotho and they can invade and raid Botswana.

When we call for sanctions we have to make an exception, it is understood. We make an exception with regard to the countries that border South Africa, because their economies are dependent on trade with South Africa. So they are not called upon to impose these sanctions. They know that if sanctions were imposed they would be the worst affected, and they say that is the sacrifice they have to make. Of course, we all hope that the opponents of apartheid who enforce sanctions would want to minimise the adverse effect on these countries. In other words, we want them to be given assistance to enable them to survive the effect of sanctions.

This article was originally published in Index on Censorship magazine in 1986.

Click here to subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine, or download the app here

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

This is the moment to remember massive changes in South African life that are Nelson Mandela’s legacy says Rachael Jolley

This is the moment to remember massive changes in South African life that are Nelson Mandela’s legacy says Rachael Jolley