7 Jul 2015 | Asia and Pacific, Campaigns, Malaysia, mobile

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar is facing charges under a colonial era sedition act. (Photo: Sean Gallagher/Index on Censorship)

Persecuted Malaysian cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Haque, who is facing nine simultaneous charges under the country’s controversial Sedition Act, has had his case pushed back until 9 September.

The artist, known as Zunar, told supporters in an email that his case had been adjourned pending a ruling from the Federal Court in a separate case that challenges the constitutionality of the Sedition Act.

The current case sees Zunar facing 43 years in prison over a tweet criticising the recent jailing of a Malaysian opposition leader. He has been targeted numerous times for speaking out against the Malaysian government in his editorial cartoons. Zunar was investigated under the sedition act for the first time in 2010, much of his work has been banned, and he has been subjected to repeated raids, arrest and detainment.

“Zunar is being prosecuted simply for exercising his right to express himself. We welcome the legal challenge to the Sedition Act; a tool the government uses to try and stifle and silence dissent from Zunar and other critics. But regardless of the outcome in that case, we reiterate our call on Malaysia to immediately drop all charges against Zunar and respect free expression,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

You can support Zunar by signing this petition to call on the Malaysian government to drop all charges against him and renew its commitment to freedom of expression.

See cartoons by Zunar and other international artists on the theme of free expression drawn to commemorate our 15th Freedom of Expression awards.

7 May 2015 | Denmark, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features

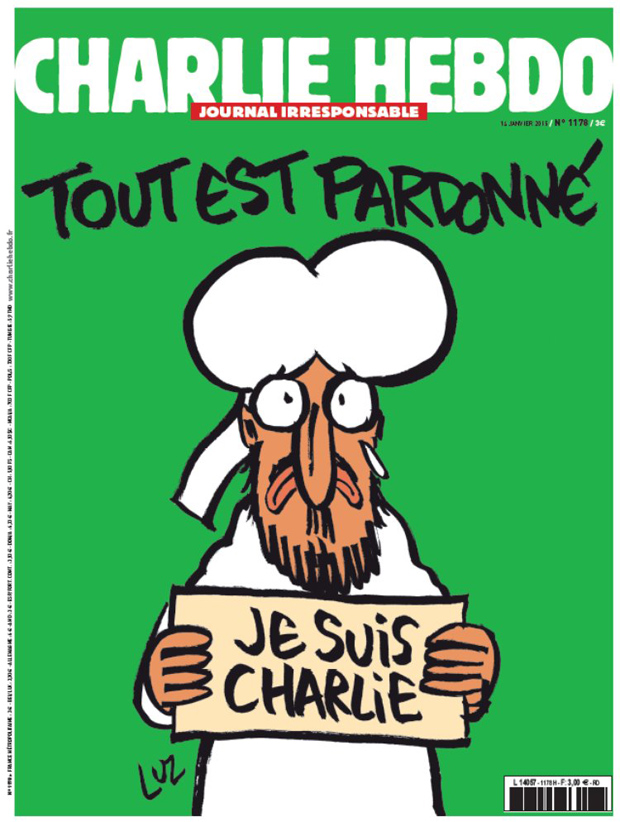

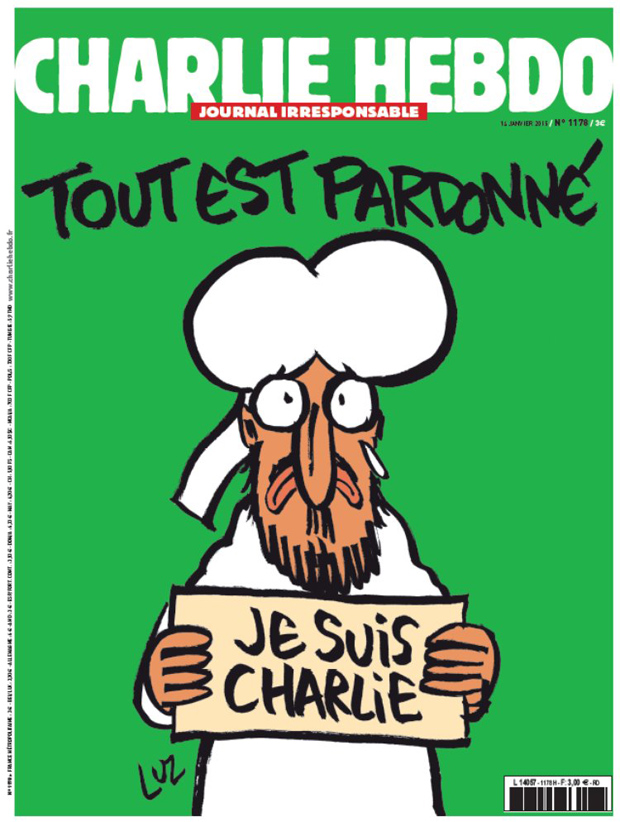

Tout est pardonne or All is forgiven, the first post attack cover of Charlie Hebdo

It’s now almost ten years since Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a set of cartoons, some of which (though by no means all) depicted the Islamic prophet Mohammed. Some were flattering, some were not. One mocked jihadist suicide bombers. Another showed a schoolboy called Mohammed calling Jyllands-Posten’s editors bigots.

The idea came after it was reported that a Swedish children’s author could not find someone to illustrate her book on the life of Mohammed. Flemming Rose of Jyllands-Posten decided to commission cartoonists to draw the apparently taboo figure.

As an exercise in taboo-busting, it was bound to be controversial. But controversial though some were (one showed the prophet as a scimitar wielding menace, another a figure with a bomb for a turban) they were not shocking enough for the Danish-based radicals who decided to make a campaign of the issue. In an astonishing act of chutzpah (there really is no other word), Ahmad Abu Laban decided to fill out a “dossier” on the cartoons with even more offensive characterisations, some of which had nothing to do with Mohammed at all. He and his colleague Ahmed Akkari took the dossier to the Middle East, apparently to prove the level of anti-Muslim hatred in Denmark. Chaos ensued. The rest, the usual line would go, is history. But that wouldn’t be true: the “rest” is very much the present, and perhaps pressing now more than at any time in the past 10 years.

One wonders if Ahmad Abu Laban quite knew what he was getting us all in to. Certainly, the man, who died in 2007, was of what is now a familiar figure in western Europe. The self-publicising Muslim spokesman: the go-to guy for a controversial quote for a press not quite sure of the heat of the flames with which they were playing. Omar Bakri Muhammad, for example, was first introduced to the British public as a ridiculous fantasist in Jon Ronson’s documentary The Tottenham Ayatollah. His proteges in al-Muhajiroun provided a steady flow of enjoyably ridiculous bogeymen such as Anjem Choudary and Abu Izzadeen, who in 2006 was given the main interview on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. Subsequent news bulletins carried his warnings of “Muslim anger” as if he were some sort of pope, rather than a fringe figure with highly dubious links.

Everyone enjoyed these outrageous figures for a while, until we realised the damage they could do. Practically every home-grown jihadist in Britain has had dealings with al-Muhajiroun. The late Laban may have known of the chaos he was about to unleash on the Middle East in 2006 with his dossier, and indeed the world ever since. He may not. His former comrade Akkari repented in 2013, saying: “I want to be clear today about the trip: It was totally wrong. At that time, I was so fascinated with this logical force in the Islamic mindset that I could not see the greater picture. I was convinced it was a fight for my faith, Islam.”

Well good, but a little late now.

Since 2005 we have been embroiled in an absurd abysmal dream. Some people draw cartoons of a long-dead religious figure. Some other people decide this has offended some sacred, though undefined, law, and so they decide that the people who drew the cartoons must be killed. Repeat. What chronic stupidity.

But of course there’s more going on here. There is more than one reason to draw or publish Mohammed drawings: from plainly making a free speech point (as many publications did after the Charlie Hebdo murders), to anti-clericalism (a la Charlie itself), to deliberate antagonism towards Muslims (a la Pamela Geller). Not all Motoons are the same.

Nor are all responses on the same spectrum. There is a world of difference between the average Muslim who may be annoyed by a portrayal of Mohammed and a jihadist who takes it upon himself to find people who have drawn these portrayals and kill them or attempt to kill them.

This is the error that has plagued the debate for the past 10 years, and came to light again in the past few weeks with PEN’s awarding of a prize to Charlie Hebdo, and the attack on a Pamela Geller-organised rally in Texas which featured a “draw Mohammed” competition.

There has been an unwitting acceptance of several dangerous ideas, chief amongst them that in order to have respect for someone as a human being, one must respect all their beliefs, and observe their taboos. But as novelist and long-time PEN activist Hari Kunzru put it: “It is not solidarity with the oppressed to offer ‘respect’ to an idea just because it’s held by some oppressed people.”

Following from this is the idea that all expression that disrespects beliefs and taboos must be driven by bigotry and racism, and that to stand against bigotry and racism is to stand against any such expression. There is a sad irony in this failure to discriminate.

On the reverse of this, some Muslims feel that free speech is now something that is being used to batter them over the head, rather than protect them. This in itself is a failure of civil society: the moment we decide everyone with a certain background and set of beliefs can be put in the “Muslim” box is the moment we ensure that those who shout loudest about those beliefs — the “extremists” — are given status. Ahmad Abu Laban, for example, claimed that his Islamic Society of Denmark represented all Danish Muslims.

So now what? As we’re approaching 10 long years of this argument, is there hope for resolution any time soon? I fear not. There can be no accommodation between those who believe in the right to free expression and those who believe “blasphemy” should carry the death sentence.

In between, if it does prove impossible not to take sides, we can at least make sure our arguments are clear and our ears are listening.

This article was posted on 7 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Jan 2015 | About Index, Awards, mobile

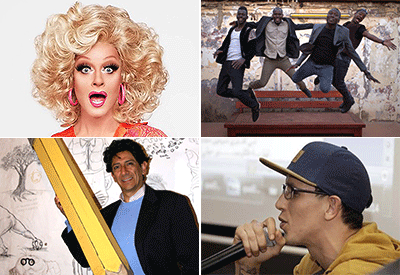

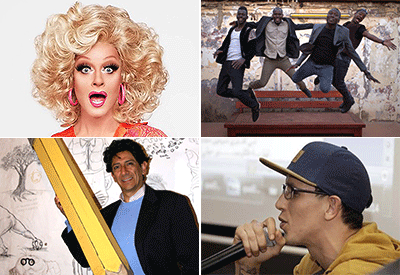

From top left: Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla, Safa Al Ahmad, Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat and Lirio Abbate are among the Index Freedom of Expression Awards nominees for 2015.

A journalist under 24-hour protection because of his reports into the Italian mafia, an Ecuadorian cartoonist facing prosecution for mocking a congressmen’s pay packet, and lawyers who challenged Turkey – and won – over its social media ban, are among those shortlisted for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards this year.

Drawn from more than 2,000 nominations, the shortlist celebrates those at the forefront of tackling censorship and threats to freedom of expression. Many of the 17 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution.

“The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise some of the world’s most courageous journalists, artists and campaigners,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index. “These individuals and groups often work in isolation, with little funding or support, but they are all driven by the vision of a world in which everyone can express themselves freely – no matter who they are or what they believe.”

Awards are offered in four categories: journalism, arts, campaigning and digital activism.

Those on the shortlist include Lirio Abbate, an Italian journalist whose investigations into the mafia mean he requires constant protection; Safa Al Ahmad, whose documentary exposed details of an unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia; radio station Echo of Moscow, one of Russia’s last remaining independent media outlets; and Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan reporter repeatedly prosecuted for his work exposing government and industry corruption.

Arts nominees include Ecuador’s censored cartoonist Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla – who has for more than 30 years critiqued and lampooned the country’s authorities; Moroccan rapper Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, whose music challenges poverty and government corruption; Rory “Panti Bliss” O’Neill, a Dublin-based drag artist who speaks out against homophobia; and Malian musicians Songhoy Blues, who fled their country after music was banned. Guitarist Garba Touré was threatened with having his hand cut off.

In the campaigning category, nominees range from lawyers Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, who played a key part in overturning Turkey’s social media ban last year; to innovative German anti-Nazi group ZDK; to Amran Abdundi, working on the treacherous Somali-Kenya border to help women and girls who are frequently victims of violence, rape and murder. They also include Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar who is working to develop a free media in Afghanistan, and The Union of the Committee of Soliders’ Mothers of Russia – a group dedicated to exposing stories of Russian soldiers, killed in the Ukraine conflict, which the Russian government denies.

The digital activism category, which is decided by public vote, includes investigative news outlet Atlatszo.hu, which is using freedom of information requests to hold the Hungarian government to account; Nico Sell, a US-based entrepreneur and online privacy activist; online map Syria Tracker, which is providing reliable data on human rights abuses in Syria; and Valor por Tamalipas, a crowd-sourced news platform set up to fill a void created by the region’s drug cartel-induced media blackout.

The shortlisted nominees:

Arts

Panti Bliss (Ireland)

Songhoy Blues (Mali)

“Bonil” (Ecuador)

“El Haqed” (Morocco)

More details

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi (Kenya/Somalia)

Zentrum Demokratische Kultur (Germany)

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar (Afghanistan)

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak (Turkey)

Soldiers’ Mothers (Russia)

More details

Digital Activism

Syria Tracker (Syria)

Nico Sell (USA)

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky (Hungary)

Valor por Tamaulipas (Mexico)

More details

Journalism

Rafael Marques de Morais (Angola)

Safa Al Ahmad (Saudi Arabia)

Lirio Abbate (Italy)

Echo of Moscow (Russia)

More details

This article was posted on 27 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, France, News and features

People marched in Paris to show their unity. Photo: European Council President / Flickr

There can be few more insulting coinages than the tedious phrase “moderate Muslim”. What does it mean? Who does it benefit? In the past week, since the atrocities in Paris, we have heard it often: “moderate” Muslims must condemn terrorism. Or, alternatively, the images of Mohammed printed by Charlie Hebdo (and others in solidarity) were alienating “moderate Muslims”: “free speech fundamentalists” must reach accommodation with “moderate Muslims”.

The suggested dichotomy — that one cannot believe in free speech and in Allah, is a dangerous one. More dangerous still is the underlying implication that the “moderate Muslim” is less of a believer than the Muslims who murder, supposedly in the name of God.

It is now eight days since a murderous gang set about killing cartoonists because they had blasphemed and Jews because they were Jews. The gang was composed of men who were Muslims (it is disingenuous, as British Culture Secretary Sajid Javid pointed out, to suggest that these people were not really motivated by Islam, unless you are willing to put yourself forward as the ultimate authority on what is and isn’t Islamic).

Since then, we have gone from revulsion at the acts of the killers to an obsessive focus on the actions of their victims (or at least their victims at Charlie Hebdo: there is relatively little discussion of the slain shoppers in the kosher supermarket).

The function of all this, unwittingly perhaps, is to reinforce a power dynamic. This is about “us” and what “we” did to “them”. “Us”, roughly, being liberal democracy: “them” being European Muslims who somehow, “we” have decided, are something outside.

Worse, we have decided that there is a continuum of “Muslim anger”, at the end of which is inevitable violence. This is to imagine a homogenous bloc of believers, and to ignore the sectarian and political struggles that exist within Islam. By ignoring these struggles, we in fact junk normal Muslims (enough of the “moderate”) in with those for whom the faith is a political project and even an imperial war with the intention of “restoring the Caliphate”.

Meanwhile, “we” have the comfort of decrying our own hypocrisy.

Crying “hypocrite” is enjoyable; indeed, it’s an essential part of how the British press, and British political and social advocacy, works. Beloved satirical institutions thrive on pointing out double standards.

But tempting though this tack is, it is not an argument in itself: yes, the French state is hypocritical on free speech, lauding Charlie while arresting racist comedian Dieudonné for a Facebook post, and announcing a “crackdown” on hate speech. Of course it is rich for world leaders to march for “free speech” when practically every single government you can think of has mechanisms for censoring its citizens in one way or another. But then what? Does that somehow mitigate the horror? Does that mean we shouldn’t stand for free speech? Does that mean, even, that censorship is OK because everyone does a little bit of it?

What is achieved by this is a focus back on our own ability to control things that seem beyond us. These attacks will stop, we imagine, when we find a way to avert them. The murderous ideology motivating these attacks was created by “us”, through, say, “our” support for the 80s jihad against the Soviet occupation in Afghanistan (as Christopher Hitchens pointed out in his 2001 article Against Rationalisation, it was the CIA that “first connected the unstoppable Stinger missile to the infallible Koran”).

But the fact our governments did some things in the past that have come back to haunt us is, again, not a reason for inactivity or passivity on our own parts now. Rather we must deal with what is in front of us, while hoping not to make mistakes that will come back to us.

It is a good and honourable thing that so many people’s instinct, when confronted with aggression, is conciliation. But loathe though my conciliatory soul is to admit it, there is nothing I can concede that will appease the ideology that led to the carnage in France. To quote Hitchens once more, what the murderers and their co-thinkers hate are the parts of liberal democracy that are worth defending: “its emancipated women, its scientific inquiry, its separation of religion from the state.”

None of these things are perfectly achieved in any society, but they should be clung to as aspirations, and defended when needs be. Moreover, they must be maintained as universal, emancipatory values. To portion them off, or worse, to present them as a weapon of one part of society against another — “free speech fundamentalists” versus “moderate Muslims”, is to give succour to those whose only perception of a universal ideal is universal subjugation.

This article was posted on 14 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org