29 May 2014 | Lebanon, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

(Photo: Lucien Bourjeily/Twitter)

Lucien Bourjeily is smiling, and with good reason. Only two days earlier, the dark blue Lebanese passport he is holding up had been confiscated by the country’s intelligence agency, with no clear information of when he might get it back. The explanation given? “You know what you did.”

Speaking to Index on Censorship from Beirut, it’s clear that Bourjeily does know. This was not his first run-in with Lebanon’s General Security Directorate. The well-known writer saw his recent play about censorship in Lebanon banned by the agency, which counts media censorship among its many roles. His play was “unrealistic”, the censors told Bourjeily, the irony of the situation lost on them.

The experience earned him a nomination for this year’s Index awards. While he couldn’t attend the awards ceremony in London, he will be travelling to the UK in June to take part in the LIFT Festival with his latest production Vanishing State, which deals with redrawing borders in the Middle East. It was his attempt to renew his passport for this trip — another area under the jurisdiction of the directorate — that led to his latest ordeal.

Bourjeily is convinced the confiscation had been agreed on beforehand. Everyone he dealt with from the general security that day were saying the same thing, despite being in different rooms. “That’s how you know the decision had already been taken.”

A public figure in Lebanon, Bourjeily’s case drew huge media attention. People across the country rallied behind him, and lawyers offered to represent him for free. “I feel very lucky to have so much support, and that my case got so much favour in the public opinion,” he says.

He believes his latest case especially strikes a chord with his countrymen and women. “Every Lebanese loves their passport,” he says. “Freedom of movement for them is even more important than any other thing. Freedom of speech and now freedom of movement? This is too much!”

But he is not the only person to experience this. In 2010, general security confiscated the British passport of Nizar Saghieh, a dual British and Lebanese citizen. Prior to this, Saghieh had represented four Iraqis who were suing the Lebanese state over illegal detention by general security. He only got the passport back following direct intervention by then-Interior Minister Ziyad Baroud. Similarly, current Interior Minister Nouhad Machnouk stepped in on Bourjeily’s behalf, personally calling the director of the general security to demand the return of the passport.

He finally got it back on 23 May, with the message that the whole thing had been “a mistake”, and there would be an internal investigation. Bourjeily is not allowed to see the results of the investigation. He asked for justification on behalf of the Lebanese people, wondering whether the agency weren’t at least going to tell the public what they’d told him — that it had been a mistake. Again, he was told no.

Bourjeily says he will add this experience to the sequel of his banned play. He has also met with Saghieh, who heard about his case in the media, and they “discussed ways to collaborate together”. He has no doubt that this, all things considered, happy ending was down to public pressure. Others might not be as lucky.

“[What] if it [was] not me? If it’s not a person who has 30,000 followers on Facebook? If it was just any regular Joe in Lebanon? What would happen to them if they confiscated their passport?”

This article was posted on May 29 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

28 May 2014 | News and features, Religion and Culture, Spain, Turkey

Last year, the exhibition Here Together Now was held at Matadero Madrid, Spain. Curated by Manuela Villa, it was realised with the support of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, Turkish Airlines and ARCOmadrid. But in the exhibition booklet, the explanatory notes to artist İz Öztat’s work “A Selection from the Utopie Folder (Zişan, 1917-1919)” was censored upon the request of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, and the expressions “Armenian genocide” and the date “1915” were taken out.The case shows how the Turkish state delimits artistic expression in the projects it supports, and how it silences the institutions it cooperates with.

After Turkey was chosen as the country of focus for the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid International Contemporary Art Fair, the designated curator Vasıf Kortun and assistant curator Lara Fresko started to work with the galleries that would join the fair. They helped in fostering connections between the Madrid arts institutions and artists in Turkey; as well as with the embassy officers in charge of the financial support of events such as Here Together Now, which would run as a parallel event to the main fair. The embassy indicated that it would support this exhibition with the generous sum of €250,000. However, it did not provide any written documentation guaranteeing this support, and outlining the mutual duties and responsibilities of the parties involved. Likewise, during the realisation of the project, there was no written communication between the embassy and Matadero Madrid, and all negotiations took place verbally, over the phone. It was in this manner that, from the very beginning, the state kept the exact conditions of its support ambiguous and created a tense situation for the organisers. Ultimately, this working practice gave the Embassy the possibility of denying the promised support, in the event that their request was not carried out.

This is not the first case of the Turkish state censoring an arts event it sponsors abroad. We frequently hear about such cases off the record, and at times through the media. One of the best-known cases of state intervention took place in Switzerland, during the 2007 Culturespaces Festival. Director Hüseyin Karabey’s film Gitmek – My Marlon and Brando, which had received support from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, was taken out of the festival program at the very last minute, at the request of an officer from the General Directorate of Promotion Fund, on the pretext that “a Turkish girl cannot fall in love with a Kurdish boy” as was the case in the film. The officer threatened the festival organisers with withdrawal of sponsorship totaling €400,000 — much like the case of the Madrid exhibition. The festival director decided that they could not go ahead with the event without this support, ceded to the censorship request, and accepted to take the film out of the program. However, independent movie theaters in Switzerland criticised this decision and ended up screening the film independently of the festival.

Both examples show that the state controls the content of the projects it sponsors abroad, interferes with the organisations on arbitrary grounds, and violates artists’ rights by threatening the very institutions it collaborates with.

The administrative channel for the state’s support to events outside of Turkey is the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s Promotion Fund Committee, established under law 3230 (10 June, 1985) with the aim of supporting activities that “promote Turkey’s history, language, culture and arts, touristic values and natural riches”. The Committee reports directly to the Prime Minister’s office, and is presided over either by the Prime Minister himself, the Vice Prime Minister or a minister designated by the PM. It has five more members: Deputy Undersecretaries from the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, as well as the general managers of the Directorate General of Press and Information, and the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT). The objective of the fund is “to provide financial support to agencies set up to promote various aspects of Turkey domestically and overseas, to disseminate Turkish cultural heritage, to influence the international public opinion in the direction of our national interests, to support efforts of public diplomacy, and to render the state archive service more effective”.

The Committee convenes at least four times a year upon the invitation of its president to evaluate project applications. The only criterion in accepting a project is whether it complies with the objectives mentioned above. After the Committee carries out its evaluation, the projects are put into practice upon the approval of the PM. Representative offices of the Promotion Fund Committee monitor whether the projects are implemented in compliance with the principles of the fund. In the case of the Madrid exhibition, the Turkish Embassy assumed the role of representative office. In this respect, as per the relevant regulation, the embassy was in charge of controlling the project, signing protocols with project managers to outline mutual duties and responsibilities, making the necessary payments, and delivering the project report to the Committee. As such, the embassy’s avoidance of all written documentation is in breach of the principles and modus operandi established by its own regulations.

Overall, it can be said that the Promotion Fund Committee does not meet the criteria of transparency and accountability generally expected from a public agency. The dates when the committee convenes to evaluate the projects are not announced, and the committee members, annual budget, sponsorship priorities and selection criteria are not made public. The sums paid to projects sponsored and the content of the projects are not disclosed officially. In other words, there is no transparency about the distribution of the funds, or about the auditing procedures. Such structural problems make it even harder to reveal and question the state’s violation of the right to artistic expression.

Another important aspect of this case is that the state constantly tries to reproduce its dominant discourse based on the denial of past and ongoing human rights violations such as forced displacement, genocide, political murders, burning of villages, enforced disappearances, rape, and torture through security forces; and does its utmost to silence any expression which contests this discourse. The centenary of the Armenian genocide, 2015, is drawing near. As such, it becomes even more important to demand that the Turkish state be held accountable for this human rights violation.

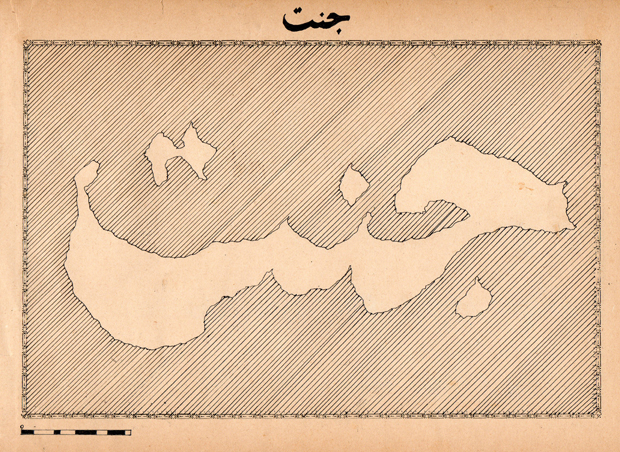

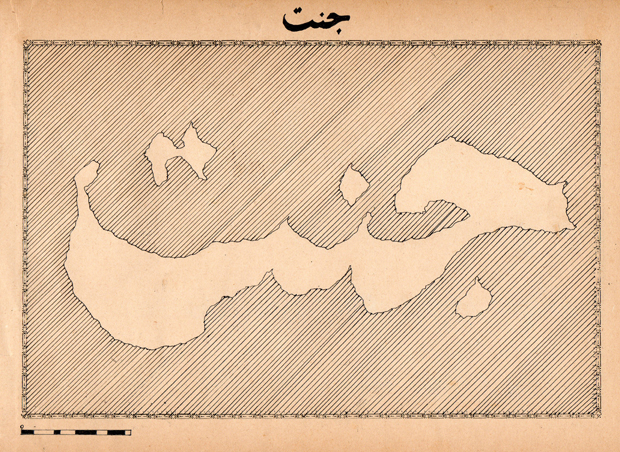

Map of Cennet/Cinnet (Paradise/Possessed Island). Zişan, 1915-1917. Ink on paper, 20×27 cm. Dedicated to the Public Domain

Siyah Bant is a research platform that documents and reports on cases of censorship in arts across Turkey, and shares these with the local and international public. In the context of this work, we wanted to investigate the censorship that occurred at Here Together Now. In accordance with the Right to Information Act, we asked the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, to explain the legal basis of the censorship they imposed on the booklet. In response, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism indicated that Matadero Madrid and curator Manuela Villa were the only authorities in charge of selecting the artists who would participate in the workshops of ARCOmadrid, designating the content of the works to be produced during the workshops, and preparing all printed matter in connection to the event. We were unable to obtain an official statement from curator Manuela Villa, despite several inquiries. Finally, we conducted an interview the artist İz Öztat to understand how the censorship took place, and how she experienced the process.

How did you come to be involved in the exhibition?

I was invited by Manuela Villa, curator of Matadero Madrid, after meeting her in Istanbul. Matadero planned for a residency program and an exhibition project titled Here Together Now to take place concurrently with the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid Art Fair that had a section consisting of invited galleries from Turkey. By the time I signed the contract with Matadero Madrid, I knew that the project was partially supported by the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and Turkish Airlines.

Here Together Now was a process that allocated the resources with an emphasis on living and working together. Cristina Anglada (writer), Theo Firmo, Sibel Horada, HUSOS (a collective of architects), Pedagogias Invisibles (art mediation collective), Diego del Pozo Barrius, Dilek Winchester and I had six weeks together, during which we figured out common concerns, negotiated our relationship to the institution’s public, designed the working and exhibition space, collaborated and produced our works.

Can you tell us about the nature of contract with the institution and if there were any limitations indicated as to the nature of your work?

We signed a very detailed contract with Matadero Madrid that laid out the responsibilities of the institution and the artist in relation to the production and authorship of new work but there were no limitations outlined in the contract. I took it for granted that the artist has freedom of expression and institutions do not interfere in the produced content.

The institution was extremely supportive of the project. They were engaged in our discussions and ready to help once we started producing the work.

Could you talk a bit about the work that you prepared for Matadero Madrid?

The work shown in the Here Together Now exhibition was part of an ongoing process, in which I imagine ways to conjure a suppressed past. Since 2010, I have been engaged in an untimely collaboration with Zişan (1894-1970), who is a recently discovered historical figure, a channeled spirit and an alter ego. By inventing an anarchic lineage with a marginalized Ottoman woman, I try to recognize a haunting past and rework it to be able to imagine otherwise. For the exhibition at Matadero Madrid, I produced and exhibited “A Selection from Zişan’s Utopie Folder (1917-1919)” accompanied by works from the “Posthumous Production Series”, in which I depart from Zişan’s work to open a path towards the future in our collaboration. The exhibited work was complemented by a publication with three interviews, which situates the work and builds a discourse around it.

Which aspect of the work was censored? How did the process of censorship occur, and what kind of dilemmas did you face in this process?

Manuela Villa, the curator, met with me in the exhibition space one evening a few days prior to the opening. Officials from the Turkish Embassy had threatened to withdraw their financial support, if the demanded changes were not made. I had to make a decision on the spot and accepted the censorship in the booklet, but not in the publication complementing the work. The exhibition booklet was reprinted and the sentence was changed to “Zişan, born in Istanbul in 1894, is a marginal woman of Armenian descent, who embarks on a European quest.”

As I said before, there was an emphasis on the community we built together during the residency at Matadero and I didn’t want to make a decision alone that would put the whole project at risk. Because of the time constraints, we were only able to meet with the other artists after the opening to discuss the precarious condition that we were all in. The institution didn’t have any signed documents from the Embassy committing to the sponsorship. Everything was communicated verbally and there was no written documentation. I was not able to reach out for a support network to resist the situation, not least due to the immediacy the decision required.

The exhibition booklet that was presented to the embassy was altered but the publication accompanying your work remained unchanged. How did the curator and other artists react to your refusal to change the publication?

I could not stand my ground with regard the exhibition booklet because it concerned everybody in the project. Yet, I was able to take full responsibility of my own work. We were informed that officials from the embassy will visit the show prior to the opening and I was ready to withdraw the work, if there was any interference. Everybody was supportive of my decision.

What happened on the day of the opening? Did you feel the need to prepare yourself?

In the end, none of the officials from the embassy came to the opening or the exhibition. There was no confrontation regarding the work. There might be a few reasons for this that I can think of. Maybe, they felt entitled to interfere with the content of the exhibition booklet because it had the logo of the embassy and could dismiss my publication since it only had the logo of Matadero Madrid. It was not of benefit for the embassy to confront me in a situation that would have made the case public.

As Siyah Bant we inquired both with the curator and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in order to understand how this censoring motion played out. Given that the ministry rejects any responsibility and instead assigns all responsibility to the curator, and that the curator was acting under the duress of loosing all funding last minute, where does this leave you as the artist? How do you make sense of what happened to your work?

Since I accepted the censorship, my only option was making the situation public after the fact. I have been working in cooperation with Siyah Bant since I got back from Madrid. It took a few months to receive an official response from the embassy, which denied all responsibility. We wanted to make the case public after receiving a statement from the curator or the institution. I was unable to receive such a statement, and Siyah Bant is working on that now.

I see it as an experience, in which I was able to test and see the boundaries of government support that is allocated to arts and culture for promoting the country. If you decide to accept this support and challenge official policies, a system of censorship starts to operate.

Next year marks the centenary of the Armenian genocide which will inevitably bring about numerous artistic and cultural reflections on the subject. Given the current climate in Turkey, how confident are you that artistic freedom of expression will be respected?

We are going through a period, in which it is impossible to make predictions about what can happen even the next day. I can only hope that genocide denial at state level comes to an end. I am sure that artists will articulate their own ways of recognising the Armenian Genocide and confronting its denial. You are probably more prepared than I am to predict and know what kinds of mechanisms are at work to limit the production and dissemination of such work.

What would be your recommendations to other artists taking part in cultural events that are supported by the Turkish government?

Based on my experience, I think that artists and art institutions need to act in solidarity in these situations. If there is funding from the Turkish state, the institutions and artists involved need to be aware that the state monitors the content. The various institutions that distribute state funding do not provide written documents about their commitments and communicate their demands mostly in person or by phone. Demanding written documentation at every step is necessary. Artists who are considering to take parts in projects that receive state funding, can demand from the art institutions to be more transparent about the budget and its workings so that they can be prepared to make alternative plans if the state funding does not come through as promised.

If I encountered the same case of censorship now, I would not feel obliged to make a decision immediately and in isolation. I would consult the rest of the group and demand the involvement of the institution.

This article was posted on May 28 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

27 May 2014 | India, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

The Vagina Monologues performed in Mumbai in 2013 (Photo: BBC News)

“If Chennai doesn’t have vaginas, it is full of a#*holes!” quipped Mahabanu Mody Kotwal in the opening act of The Vagina Monologues when it was staged in Mumbai. The veteran theatre actor and director had good reason for using the pun. In December 2010, when the play was to be staged in the city for the first time, the Police Commissioner played spoilsport at the eleventh hour and declined permission. Earlier this year, a play on the Partition of India wasn’t allowed to be staged in Bangalore, and yes, Chennai. In both cases, it was the police which called the shots in the cancellations. Theatre’s subversive and liberating potential is renowned, and governments the world over have never held themselves back from wielding the censor’s bludgeon, but in India, it is the police which has been vested with remarkably sweeping powers to crack down on theatrical performances.

However, Chennai’s travails might well be over because in January this year, the Supreme Court struck down those provisions of the legislation – The Tamil Nadu Dramatic Performances Act, 1964 which permitted the cops to be the sole arbiters of “suitable” drama in the first place.

The roots of this legislation go back to the days when India was under British rule and the colonial administration remained constantly paranoid about “the natives” being up to mischief. Their fears were precipitated in 1876, when a Bengali play “Neel Darpan” (A Mirror to Indigo) was staged in Calcutta and got a rousing response, even from many Englishmen. The play narrated how farmers in Bengal and other provinces were being forced to cultivate indigo, and if they refused, were meted out the most terrible of punishments. This made the livid rulers who termed the play “scurrilous”, enact a law “to empower the government to prohibit certain dramatic performances”. The stated object of this law was to “prohibit Native plays that are scandalous, defamatory, seditious, obscene, or otherwise prejudicial to public interest”. Of course, “otherwise prejudicial to public interest” was left undefined, further empowering the censors.

It was hoped that independence would free drama from the shackles of this repressive law, but the reverse happened. Different states in India brought in their own legislations to control theatre, and most of them tightened the grip more than the British ever did.

For instance, the present legislation was geared towards proscribing “objectionable” plays and pantomimes. Section 2 (1) defined “objectionable” as anything which was likely to:

be seditious

(i) incite any person to commit murder, sabotage or any offence involving violence; or

(ii) seduce any member of any of the armed forces of the Union or of the police forces from his allegiance or his duty, or prejudice the recruiting of persons to serve in any such force or prejudice the discipline of any such force;

(iii) incite any section of the citizens of India to acts of violence against any other section of the citizens of India;

(iv) is deliberately intended to outrage the religious feelings of any class of the citizens of India by insulting or blaspheming or profaning the religion or the religious beliefs of that class;

(v) is grossly indecent, or is scurrilous or obscene or intended for blackmail; and includes any indecent or obscene dance.”

Thus, one is left in no doubt that the only form of ‘non-objectionable’ theatre would be bland, pantomimes extolling the virtues of mythology and religion; even then, one could never be sure, because religious sentiments in India are nothing short of a communal tinderbox.

If these antediluvian definitions weren’t enough, the police could act against the producer, director, troupe, and even the person who either owned or let out the premises where the play was to be staged. And there lurked the gravest danger- carte blanche powers of pre-censorship. Scripts of plays were to be submitted to the police for approval, and even though an opportunity of hearing was provided before the final call could be taken, it was hollow formality because the history of the legislation’s implementation proves that permission was granted only when the director or the playwright agreed to some of the mandated excisions.

In fact, the government was so unwilling to relinquish control that it told the Court of its willingness to appoint an officer to “guide the police commissioner in the cultural nuances” since literary sensibilities aren’t usually policemen’s forte!

The Supreme Court has broken the police’s stranglehold in Tamil Nadu; the time is ripe for challenging similar laws proscribing dramatic performances in other states and restoring to theatre the freedom it always deserved.

This article was posted May 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 May 2014 | Academic Freedom, News and features, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

“Once upon a time there lived in Berlin, Germany, a man called Albinus. He was rich, respectable, happy; one day he abandoned his wife for the sake of a youthful mistress; he loved; was not loved; and his life ended in disaster.”

So begins Vladimir Nabokov’s Laughter In The Dark, a terse, tragic little book. There’s really not much more I can tell you about it, apart from the fact that the “youthful” mistress is uncomfortably so, Albinus says and thinks some quite sexist things about women, and he ends up disabled (and worse).

Perhaps then, in light of recent requests from English Lit students on American campuses that teachers should provide “trigger warnings” for novels that could contain traumatising themes and scenes, this already revealing opening could be rewritten:

“Once upon a time there lived in Berlin, Germany, a man called Albinus. He was rich, respectable, happy; one day he abandoned his wife for the sake of a youthful mistress; he loved; was not loved; and his life ended in disaster. TRIGGER WARNING: sexism, cis-sexism, borderline paedophilia, violence, ableism.”

Would that be so bad? Clumsy, no doubt, but does it really affect the reader’s experience, or, specifically, the academic learner’s ability to analyse the book? Well, yes, in that it skews one’s expectations, forces one immediately to think “this is a book about misogyny, violence, and disability,” rather than a book about say, the upheaval of interwar Europe, the clash of old and new, or just good old hubris: things Laughter In The Dark are actually about, rather than things that happen in Laughter in the Dark.

The trigger warning has its origins in online forums dedicated to specific topics, and in the backlash against the idea that has happened this week, some commentators have pointed out that this is an imposition by one small community on general society: Jonah Goldberg in the LA Times, for example, unfavourably compared those calling for trigger warnings on campus to Amish people, pointing out that the Amish would prefer not to have to deal with a lot of the modern world, but at least they don’t inflict their desires on other people.

It’s a tempting “who do these people think they are” argument, made all the more so enticing by the intergenerational aspect – pretty much every person I know over the age of 30 finds the “social justice” movement, from which ideas such as trigger warning have sprung from, equal parts infuriating and baffling. It feels like a world of endless taboos and astonishing sincerity, far removed from the heavy irony that, for better or worse, characterised the generation that preceded it.

And they don’t like us much either: writing for Vice last week, Theis Duelund denounced Generation Xers, born between 1965 and 1980, as “slackers [who] nihilistically accept the machine of which they are a part, and can dissect its fundamental facile and evil nature with all the clarity and urgency of a nineteenth-century Romantic poet.”

(If Theis wants to play that game, I’m creeped out by a generation of people for whom dressing up as something out of My Little Pony seems an acceptable subculture for an adult to be involved in).

But changes rarely come from spontaneous mass movements; more often than not, they come from persistent nagging from a minority (or “campaigning” as it’s more kindly called), who eventually convince the rest of us. So to complain that things such as trigger warnings are being foisted upon us by a small group of millennial social justice activists is to avoid the argument about generalised trigger warnings for literature themselves.

The argument being this. Art is an expression of the human condition; our urge to create art, and to consume art, is in large part driven by our need, as social animals, to communicate, to empathise and sympathise.

What that does not mean, however, is that a work of art should, or will, provoke a specific response. Alain De Botton, the writer of philosophically styled self-help books, has recently suggested, through an exhibition he has curated at the Rijksmuseum, that we can use art for self-improvement, implying that specific works inspire specific emotions. It’s a silly, reductive, anti-human argument, implying that there is a correct way to view art, and a correct single message to be taken from it.

Much of the discussion around trigger warnings, and indeed broader discussion of the modern “social justice” movement, is similarly anti-nuance. In the eyes of the online social justice activist, questioning is tantamount to discrimination. This, I believe, is partly generational – asking someone to explain something seems strange to generation just-fucking-Google-it, but as I’ve said, we shouldn’t make age the issue here.

The worry is that in an effort to protect individuals, we risk destroying empathy. The social justice term “allies” has replaced the old fashioned idea of “comrades”. You can support people’s struggle from a distance, “ally” suggests, but you cannot stand with them, because you do not understand the entirety of their experience. It implies a lack of faith in human imagination, in our ability to think outside of ourselves, and in the complexity of the human condition.

So it goes with the trigger warning: there seems little belief here in the idea that a work of fiction could tell us something bigger about the world, could help us understand our fellow beings; or even that reading about experiences that mirror your own may actually help, may make you realise that you are part of something universal. Blood-and-guts fantasy fiction such as Game of Thrones seems to escape opprobrium, perhaps exactly because it’s not seen as being anything to do with the bad things that happen in the real world.

The message and tone of the “trigger warning” suggests a sad lack of faith in the power of art, and, by extension, humanity. We’re capable of better.

This article was posted on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org