17 Sep 2013 | Asia and Pacific, News, Religion and Culture, South Korea

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.

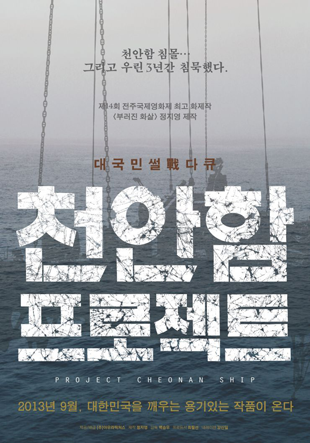

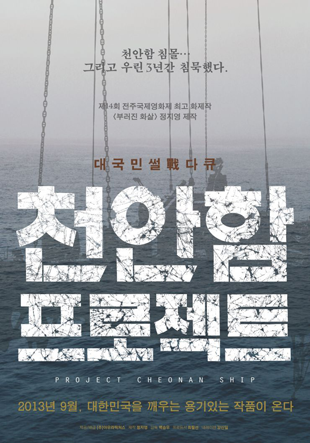

Project Cheonan Ship is a film on the aftermath of the 2010 sinking of the Cheonan warship, a South Korean navy submersible that went down in waters near North Korea. South Korea concluded that a North Korean torpedo was the cause of the sinking, though North Korea denied any involvement. The film features experts in a range of fields offering possible alternative causes of the ship’s sinking.

In August, members of the South Korean navy and relatives of a few of the 46 sailors who died in the sinking sought a court injunction to prevent the film’s release. “There is freedom of expression, but no freedom of distortion…If the movie is released, it could defame the reputations of the 46 fallen soldiers and their bereaved families”, the group’s lawyer said in a statement.

The injunction was denied in court and the film opened according to schedule on Sept. 5 at 30 theaters across South Korea, mostly in independent film houses but in a few major theaters as well. It did well on its opening weekend, ranked first among independent films and eleventh overall at the box office.

After two days, the film was pulled by Megabox, a major theater chain. This is believed to be the first time in Korean history that a film has been pulled in this way. Megabox said that they had received warning from conservative civic groups who planned to picket the theaters showing the film. The theater company said they didn’t want to put viewers’ safety at risk, and therefore stopped showing the film to avoid trouble.

A big part of the reason why the issue of the Cheonan sinking is still prickly is that there was a long debate over the cause of the sinking and though the evidence strongly points to North Korea, there still isn’t a uniform consensus on what happened. An international investigation commissioned by the South Korean government eventually concluded that indeed, a North Korean torpedo had sunk the Cheonan. Skeptics continued to argue that the ship could have come in contact with a mine leftover from the Korean War.

The debate over the sinking has been split along the lines of South Korea’s political divide: conservatives who support the South’s military alliance with the US and are bitterly opposed to North Korea, and those on the left who don’t approve of the large US military presence in South Korea and see it as the main obstacle to peaceful reunification with North Korea.

People in South Korea who voice either explicit or implied support or sympathy for North Korea are often shouted down. There is even a law banning expressions ofsupport for the North: Article 7 of the National Security Law (NSL) stipulates up to seven years in prison for anyone who “praises, incites or propagates the activities of an anti-government organization”. Under the law, North Korea counts as just such an anti-government organization.

While supporters say the NSL is necessary to protect a fragile peace against the North Korean threat, critics say it is a vaguely worded prohibition that is really meant to stifle dissent within the country.

The makers of Project Cheonan Ship intended not to take a position on the cause of the Cheonan sinking, but to start a conversation about the importance of unimpeded expression of differing views. “Our primary motivation was not telling a story about the Cheonan sinking case itself, but about the intolerant attitude seen in our society after the incident,” Director Baek Seung-woo said in an interview on Sept. 13.

Baek said he and the other filmmakers wanted to reiterate the importance of free speech in South Korea. “We made this movie because we believe most people in our society have an understanding of what free speech means, but don’t yet fully appreciate its value,” he said.

Even after making the film, they still don’t attempt to make definite claims on how and why the Cheonan went down. Baek explained, “While making the movie, I realized how extremely difficult the case was. I am not expert on marine science or military equipment or explosives. I’m not scientist either. I don’t know what the cause is, but I think the real experts in our society need a more open climate of free speech to really figure out what happened.”

This article was originally published on 17 Sept, 2013.

9 Sep 2013 | Religion and Culture, Russia

A criminal case has been opened against American band the Bloodhound Gang in Russia, after bassist Jared Hannegan shoved a Russian flag down his trousers at a concert in Ukraine.

Russian Investigative Committee spokesman Vladimir Markin said: “A criminal case has been opened against James Moyer, Jared Victor Hennegan and other unidentified persons on counts of inciting enmity and humiliating human dignity.”

The band are accused of desecration of the Russian flag, which is illegal under Article 329 of the Russian Criminal Code and is punishable by up to a year in prison.

The incident took place on 31 July during the band’s gig in Odessa, Ukraine. They have already been banned from entering Ukraine for five years after a similar stunt involving the Ukrainian flag at an earlier concert in Kiev. They faced charges of hooliganism and desecration of state symbols.

The band’s concert at the Kubana festival in the Krasnodar region of Russia was cancelled by Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky. They were also attacked in the lounge at Russia’s Anapa airport by local activists.

“I find the actions of Bloodhound Gang disgusting. I also condemn the act of violence against them,” American ambassador Michael McFaul tweeted at the time.

“Any artist, who wants to come and visit us, should understand that it is not just appropriate to respect the laws of their own country when they are at home, but Russian laws when they are in Russia,” State Duma Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Alexei Pushkov said in a statement at the time.

Hannegan has reportedly apologised for the incident, explaining that they didn’t mean to cause offense and that it was simply part of a band tradition that items thrown on stage go through the bassist’s trousers.

27 Aug 2013 | Index Reports, Mexico, News

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Mexico was transformed in 2000, when the National Action Party, PAN, was elected to power, ending a 70 year control by the Institutionally Revolutionary Party, PRI.

During the PRI years, self censorship was rampant in the country, as the government imposed a heavy handed control of the national media. PAN candidates ruled for the next 12 years, from 2000 to 2012. But the PRI returned to power last December, due to electorate fatigue with former President Felipe Calderon’s war on drugs.

The country has faced increasing challenges from organized crime gangs that were targeted during the Calderon government and it has had serious impacts on press freedoms in the Mexican provinces, where most media recoiled from reporting on organized crime-related violence.

In the move to control organized crime groups, the Mexican government has increased its surveillance capacity. It has also engaged in human rights violations, which according to international organizations, such as Human Rights Watch, have only exacerbated the security situation.

There is little media regulation and zero artistic censorship. But in the name of protecting the state from organized crime, the government has introduced various edicts and laws that could affect the rights of citizens.

In March 2012, the Mexican Congress approved new legislation that gave police more access to online information. Also between 2011 and 2012, the Secretariat of National Defense, which controls the Mexican Armed Forces, purchased advanced domestic surveillance equipment. The new equipment includes mobile phone and online communications software that can be openly used to monitor Mexican citizens.

In 2012, the government of the State of Veracruz introduced a public nuisance law that sends to jail any social media member who uses Twitter or Facebook to warn fellow citizens about violence. The law was set in place because two Twitter users warned state residents of shootouts that turned out to be false alarms, but had the city of Veracruz traumatized by the alleged reports. The problem remains that bloggers, and social media users have become alternative sources of information because the traditional media in at least half of the territory of Mexico are afraid of reporting on drug related violence.

Drug traffickers also retaliated against social media users. They killed at least two bloggers in the northern state of Taumalipas and also two Twitter users, whose bodies were never identified and were found hanging from a bridge overpass. Two websites that made a name for themselves by running stories and reports on drug trafficking activities around the country were forced to shut down because of direct attacks.

Twitter, Facebook and YouTube have been extremely useful sources of information in Mexico. Abuses of authority against indigenous people or by children of the powerful and well-connected have been exposed in videos that turn viral in the web and have helped to right wrongs that would have gone unnoticed otherwise.

Several laws have been passed that are supposed to help people affected by the war on drugs. There is a General Victims law that was approved by Congress by which is still not implemented. Similarly, Congress approved a federal protection mechanism for human rights defenders and journalists, but the law has been criticized by freedom of the press organizations, as having few resources and focus.

Mexico declared federal defamation laws illegal in 2007, however, about a dozen states still have those on the books. At the federal level, a person can still sue an author for moral damage. At least two critical book writers, who have written books accusing government officials of corruption, have been hit with lawsuits in the last two years.

Media ownership remains potent in Mexico. Several dozen national newspapers are published daily, and many more digital news outlets have opened in the last two years.

What was not opened until June 2013 was broadcast media. Only two news outlets were for long able to transmit television signals nationally through open television channels. They were Televisa and Television Azteca, which are owned by two of Mexico’s wealthiest citizens. However, with a new Telecommunications law that was approved by Congress in June 2013, Mexico will be able to have two more open signal channels. Another wealthy Mexican, Carlos Slim, who owns an internet-based television network called Uno Noticias will probably benefit from the new law. The new legislation will also promote the installation of a broadband Internet network nationwide.

There are 41 million Mexicans who use the internet, according to the Mexican Association of Internet. The states with the highest number of internet users are in Mexico City, State of Mexico and State of Jalisco. The average daily use of the web ranges from four hours to nine minutes. More than 90 percent of all Mexicans using the internet also use social media.

Artistic Freedom

Artists have enjoyed unprecedented freedom to be creative in Mexico. The only problem lies with the commercial theatre network, which tends to not keep Mexican made movies long enough in exhibition. One movie that is critical of the legal system in Mexico City and the tradition by local police of grabbing innocent people and accusing them of murder and other crimes, Presumed Guilty, has faced serious challenges because of what appears to be an alleged concerted campaign by a Mexico City legal group that has stopped the film from showing in the country because of multiple lawsuits brought on by people who are shown on the film, and who never signed an agreement to appear in the movie.

This article was originally published on 27 Aug, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Aug 2013 | Digital Freedom, Index Reports, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Though it has a reasonably good freedom of expression environment, the United Kingdom is wrestling with the fallout from mass surveillance leaks, press regulation, web filtering and social media guidelines. With an unwritten constitution, the right to freedom of expression comes from the practice of the common law, alongside the UK’s accession to international human rights instruments.

There have been positive developments in the UK on free speech in the last year with reform to defamation law and reform of section 5 of the Public Order Act.

The law of libel has been reformed by the Defamation Act which received Royal Assent on 25 May 2013. The reformed law, when enacted will restrict “libel tourism”, bring in a hurdle to prevent vexatious claims, update the provisions on internet publication, force corporations to prove financial loss and introduce a reasonable public interest defence. This reform will strengthen freedom of expression protections for academics, journalists and bloggers, scientists and NGOs.

Free speech is also enhanced by the United Kingdom’s strong Freedom of Information laws. Information requests are on the whole free with over 90% of requests receiving a response on time.

The recent Justice and Security Act can be used to exclude the media from hearings to consider whether a secret evidence procedure is to be used. This may cover cases where claimants have been subject to extra-judicial detention, torture and extraordinary rendition, affecting the media’s ability to perform its watchdog function.

The UK has tough state secrecy legislation. The public interest defence in the Official Secrets Act was removed in 1989 and has not been replaced.

While the freedom to protest is well-established, the use of “kettling” to deter protestors and the prosecution of “offensive” protest including the burning of military symbols and homophobic street preaching is of concern. Scotland’s recent anti-sectarian laws have criminalised “offensive” speech at football matches.

Media freedom

The publication of mass surveillance revelations by The Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald has had reverberations around the world. The UK government has moved toward confrontation with the news organisation by forcing the destruction of hard drives that contained documents leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. The recent developments around the detention of David Miranda and the seizure of material he was carrying under Section 7 of the Terrorism Act has raised concerns over press freedom.

The UK fares well internationally for media plurality with 23 independent national newspapers, as well as several hundred regional and local papers. The main TV stations are all available with every station provider. While Index believes there is strong media plurality in the UK at present, the legal framework may not be sufficient to ensure plurality in the future, as demonstrated by News Corporation’s attempted takeover of BskyB.

The phone hacking scandal exposed criminality in the British media, yet the response to the scandal has imperilled media freedom. The creation of a Royal Charter drawn up by the three main political parties to create a media regulator warranted the first government interference into the process of press regulation since 1695. Considerable confusion remains since no newspaper has agreed to be part of the new regulator. This leaves the possibility of independent regulation in the near-future.

Digital freedom

The UK upholds online freedom in comparison with other comparable democracies, but there are worrying trends on the criminalisation of social media, mass surveillance and proposals to introduce web filters.

The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 increased the powers of the police to intercept communications. In 2012, the government attempted to extend this surveillance with its draft Communications Data Bill. The Bill would have made the surveillance and storage of UK citizens’ communications data the norm allowing an intrusion into the privacy of British citizens that would have chilled free expression. The Bill was dropped after a parliamentary committee criticised the scope of the legislation, but the Home Secretary has indicated she would like to bring forward a similar law.

Revelations of cooperative relationships between the United State’s National Security Agency and the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters as part of the mass surveillance programmes has raised serious concerns around digital freedom of expression. At the same time it is surveilling citizens’s online communications, the country is in the initial stages of possibly instituting opt-out web filters to block pornography with a consultation set to begin on 27 Aug.

The framework for copyright also has the ability to impede freedom of expression. The Digital Economy Act contains provisions allowing the government to order internet service providers (ISPs) to block websites and suspend accounts for customers accused of downloading copyrighted material.

The UK has high levels of take-up of social media and internet access. However, access is still not universal with exclusion from the internet for marginalised individuals a barrier to free speech. The recently launched Web Index report shows that the UK leads in the use of online citizen e-petitioning.

The police and executive bodies make a significant number of takedown requests to remove content according to Google’s transparency reports.

There have been an increasing number of arrests and prosecutions for ‘offensive’ comments on social media after public complaints. The Crown Prosecution Service has produced guidelines to limit the number of arrests and prosecutions. The legal framework has also been reformed with Section 5 of the Public Order Act no longer criminalising insulting behaviour or content. However, restrictive laws still apply with Section 127 of the Communications Act criminalising “grossly offensive” comments.

Artistic freedom

The UK continues to produce challenging art in a free environment for artistic freedom of expression but a chill remains around social, religious and cultural pressures on the arts and inconsistent policing of art deemed to be offensive.

A lack of guidance on the policing of culture has on occasion created significant problems for artistic freedom of expression. Large demonstrations outside performances of Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti led to the play being closed down after guidance from the police. Her play about this situation, Behud – Beyond Belief was treated as a potential threat to public order with the police in Coventry asking for a fee of £10,000 per night. Policing can also be arbitrary. In 2012, a police officer told a Mayfair art gallery to remove a photo-montaged image of ancient myth Leda and the Swan from its window, despite the fact no one had complained.

While direct censorship of the Arts remains uncommon, self-censorship by artists is more routine. Artists self-censor for a number of reasons including fear of causing controversy or offence combined with special interest group campaigns that put pressure on artists to censor, financial pressures with artistic institutions not wanting to court controversy, cultural diversity policies that may encourage self-censorship and a habit of risk aversion that leads cultural institutions to focus on worst case scenarios of what might happen when taking artistic risks.

This article was originally published on 23 Aug, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org.

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.