Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“Art doesn’t divide society, it reveals division,” said Julia Farrington, Index on Censorship’s associate arts producer, at a Risks, Rights & Reputations session at the Young Vic theatre in London on 15 November.

RRR is a training programme developed by Index, What Next? and Cause4 to help art and cultural leaders understand and challenge a risk-averse culture and incorporate these topics within their organisations.

The event kicked off with guests giving a three-worded description of what risk means to them. “Vulnerable”, “essential” and “unavoidable” were among the recurring submissions.

The discussion centred on freedom of expression and the police. Farrington talked about the artist Mimsy’s piece ISIS Threaten Sylvania, which satirically depicts Sylvanian families being terrorised by ISIS through the representation of children’s toys. The artwork was removed from the Passion for Freedom exhibition at London’s Mall Gallery in September 2015 after the artist was given an ultimatum to pay £36,000 for six nights of security protection or to take it down. His decision was clear.

Guidance from the College of Policing recommends artists to take precautionary steps before making a piece of controversial artwork public. First, an artist should seek the upper-most authority and explain their artwork beforehand to avoid cancellation. Then, they should communicate with the local police. There are other actions an artist can take in these situations like have lawyer involvement, but the most effective is to share the artwork in advance to authorities.

Speaking alongside Farrington were Diane Morgan, director of Nitrobeat, and Helen Jenkins, a consultant for Cause4. Morgan held a segment on how organisations can manage difficult subjects, including dialogue and engagement.

In the last segment, Jenkins, who has over 20 years experience in fundraising, talked about raising money ethically and the importance of a trustee’s duty to protect their organisation: if funding is coming from an unethical or compromising source, should the organisation reconsider accepting?

These three voices combined into one vital day of training for CEOs and trustees on navigating the rights and responsibilities of art and dealing the daunting, risky and time-consuming environment that comes with working with sensitive art.

Photographs by Leah Asmelash[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_media_grid grid_id=”vc_gid:1542885576234-b6a1fb2f-e5c5-7″ include=”103773,103772,103771,103760,103762,103763,103764,103769,103774,103768,103766,103765″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103514″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

This attraction is entitled: How I Stopped Worrying and Learnt To Love the Muslims

Mummy: “He’ll perform for you, just keep feeding him with money.”

Little Girl: “Look mummy, he won’t stop smiling, he must be happy. But he doesn’t say anything. Does he have nothing to say?”

Mummy: “Why should he say anything? You decide what he says. Look, that’s why they’ve left some pens and paper here. He then learns what you’ve written, word for word. He can be anything you want. That’s why he’s called No One. Every day is new for him. The days before have no meaning, he has no memories. That’s why he needs new stories which we write for him.”

Little Girl: “He doesn’t have his own stories?”

Mummy:(laughing), “No! Of course not. I think they used to let them speak but no one could understand what they were saying. It was gibberish…”

Little Girl: “I feel sorry for him.”

Mother: “It was sad but then he got angry and it started to upset other children, and then the parents got angry, so they decided to keep them all silent.”

***************************************************************************

“I gesture a lot, but I try not to wave my hands around too much in public, because you know, being a black woman, people might think I’m mad.”

I met Pauline briefly during a project in Leicester when she told me this without fanfare or drama. This was an everyday check for her, a way of surviving and not drawing attention to herself. It was a response to a political and social climate where the most innocuous gestures can seem dangerous.

W.E.B. Du Bois writes about this sense of being scrutinised in The Souls of Black Folk: “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”

What does it say about our society, when some of us are censoring our most natural actions in order to fit in? Where there is a feeling that particular gestures or words will have undesired consequences, or worse, lead to some kind of punishment. Where there is a fear that society will take a course of action that will permanently scar your future.

What is the response to a pervasive fear of self-expression? Isn’t this where the arts suddenly become vital?

In all of our work at Maslaha, whether it is our criminal justice projects such as All We Are – www.allweare.org.uk or our Muslim Girls Fence project – www.muslimgirlsfence.org – or our education work – www.radicalwhispers.org – artists are a vital part of the process. They help to raise our voices above the din that shouts down granularity and applauds conformity.

When everyday language and communication begins to stunt the imagination, the arts do a side-step and show us a new perspective and horizon, where previously there was just the fog of hollow words.

But the fear of the Muslim is not producing that side-step. At a time when the Muslim communities’ imagination is being rigorously patrolled by the Prevent duty – Section 26 of the Counterterrorism and Security Act places a legal duty on public services such health and education to report signs of radicalisation — our major arts institutions are not rising to the challenge of responding to and exploring a significant abuse of free expression. I have been approached by a number of producers and artistic directors who want to respond, but don’t have the vocabulary, feel unequipped to navigate these unfamiliar and disturbing waters. There are other producers and institutions, however, who are either afraid or seem unable to focus clearly on this issue seeing Muslim communities as flickering, inarticulate shadows on the wall.

But where has this fear come from and how can it have such a concrete impact on people’s lives. Warwick University’s, Counterterrorism in the NHS report, explains how the Prevent duty operates in the pre-criminal space. “This is not a recognised term in criminology, social science, or the healthcare professions.” This is uncharted territory, and summons up the spectre of George Orwell’s 1984 thought police. The report goes onto state: “The United Kingdom is the only nation in the world to deliver counterterrorism within its education, healthcare and social care sectors as safeguarding.” Yet, the question we have to ask ourselves is, how can a policy that is so pernicious to children and young people be described as safeguarding.

Based on the government’s own statistics in 2015/2016, nearly two-thirds of referrals to Prevent were linked to Islamist extremism – 4,997 Muslims. The data shows that three in 10 were under 15 which is nearly 1,500 young people, but only 108 were deemed to require counter radicalisation support. This would be like telling the parents of nearly 1,400 Muslim children we think your child is being harmed. Actually, sorry, we were wrong. If 1,400 middle class white parents received a phone call tomorrow wrongly suggesting that their children had been radicalised, what would happen then?

Talk to parents where referrals have been mistaken, and they will say how they carry around a shame and stigma for months, not telling anyone, even though neither they nor their child has done anything wrong. The statistics hide the fear and mental burden that is insidiously creeping into homes and threatening to become the norm. And yet a cold calculation has been made by successive governments that despite the evidence presented about the negative effects of Prevent on Muslim communities, it does not warrant a change.

What this has meant is that whole communities are censoring themselves, parents are avoiding having conversations about politics or religion in case their child says something at school that could be misconstrued. I have spoken to teachers who are avoiding contentious issues in case a student says something that has to be reported.

We have a generation of young Muslims potentially afraid to express themselves and learning that if you are challenging, the state will respond no matter how young you are. Primary school children have now become potential threats to our way of life the argument goes.

Artists, some at the margins of the arts landscape, have been responding to this political and social environment. Mainstream arts organisations must recognise these voices and produce art that responds to this challenge to imagine freely and express freely. What is stopping this? Is there a fear of responding creatively to this controversial issue or is it that the typical white/male/middle class/middle-aged producer does not have his ear attuned to different narratives?

The “Inconvenient Muslims” who are much closer to the scuff and hurt of life are avoided at all costs because their stories are too complex. They don’t fit the formula of producing stories that serve to deaden inquiry and ambiguity.

This poses a different danger. Nature doesn’t like a vacuum, and recognising that the Muslim voice is missing from our collective story-telling, we risk that an inauthentic trusted white artist or “safe Muslim” will be recruited in order to do justice to those stories.

The arts organisations will feel that this is a job done, that lack which existed no longer does and we can all move on. But these stories are rootless, nourished by expediency rather than heritage and memory. We’re not willing to emulate the safe, smiling Muslim because as Audre Lorde writes, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”.

If you’re a public arts institution you have a duty to tell the stories that are not being told, otherwise, why do you exist? But you must also have that artistic urge, no? To be challenged, to hear artists unsettle you, to be startled by new ideas. If not, why do you exist? In the long term if the arts organisations play too safe, society as a whole will lose out.

There is a rich spectrum of artists working in this area such as Javaad Alipoor, Nadia Latif, Zia Ahmed, Alia Alzougbi, Aliyah Hasinah, and Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan. These are more well known but they have all struggled and continue to struggle to ensure they can create freely. There are many more who are creating in this rich radiation who should be recognised.

The philosopher John Dewey emphasised the need to engage with the rough grain of difference in order to see the great moments of truth in art. He thought resistance would make the artist grow. And the same can be said of arts institutions who should not stop seeking new artists who may make them feel uncomfortable. Otherwise we are losing stories, stories so powerful that they cannot be contained within buildings, that spill out onto the streets, cling to the air and to your skin and clothes – and there is no way of shaking them off.

And when our rights are under threat it is these stories that demand we bear witness and challenge and refuse to be silent.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css=”.vc_custom_1510749691901{padding-top: -150px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103510″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]

“In recent years there have been an increasing number of high-profile cases raising ethical and censorship issues around plays, exhibitions and other artworks. Censorship – and self-censorship – can stand in the way of great art. That’s why Arts Council England is committed to supporting those organisations who are taking creative risks. It’s important that organisations are aware of relevant legislation and the excellent guidance that exists. This programme is an important step in ensuring that our sector can continue to create vital, challenging, and risk-taking work.” – Sir Nick Serota, chair of Arts Council England

Navigating the rights and responsibilities of art that explores socially sensitive themes can appear daunting, risky and time-consuming. We have seen work cancelled or removed, because it was provocative or the funder controversial. But, for arts and culture to be relevant, dynamic and inclusive, we have to reinforce our capacity to respond to the most complex and provocative questions.

“This important and necessary project is a great opportunity to learn and discuss with others the increasing challenges we face in the arts sector, particularly in the context of socially engaged practise and public spaces.” – Mikey Martins, Artistic Director and Joint CEO, Freedom Festival Arts Trust

The session addresses the challenges and opportunities related to artistic risk and freedom of expression. It aims to encourage participants to voice concerns and experiences within a supportive environment and programme of presentations, discussion and group work. By the end of day participants will:

The session is open to artistic directors, CEOs, Senior management and trustees of arts organisations.

To date, RRR sessions have been delivered in Manchester, London and Bristol, with Arts Council national and regional offices and in partnership with the Freedom Festival Arts Trust, Hull.

“I feel more confident to speak up when talking to leaders about policy, process and practice when it comes to issues around artistic risk-taking / freedom of expression and ethical fundraising. I feel more empowered to be a useful, knowledgeable sounding board for the organisation’s I support than I did previously.” – Relationship Manager, Arts Council England[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][vc_column_text]

We are currently accepting bookings from CEO/Artistic Directors, Chairs, individual Board Members and senior team members across the country for our upcoming RRR training sessions:[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Date[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]ACE Region[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Venue[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Host[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Trainers[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Tickets[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]15 November 2018, 12:30 – 17:30 [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]London[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Young Vic Theatre[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Kwame Kwei-Armah (Artistic Director)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Julia Farrington, Index on Censorship;

Michelle Wright, Cause4

Diane Morgan, director Nitrobeat[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Book tickets for the Young Vic Theatre session[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”103263″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Host: Kwame Kwei-Armah, Artistic Director, Young Vic[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]21 November 2018, 12:30 – 17:30 [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Midlands[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]New Arts Exchange, Nottingham[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Skinder Hundal (CEO of New Art Exchange) and Sukhy Johal, MBE (Chair of New Art Exchange)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Julia Farrington, Index on Censorship;

Helen Jenkins, Cause4;

Diane Morgan, director Nitrobeat[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Book tickets for New Arts Exchange session[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”103262″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Host: Skinder Hundal, CEO, New Art Exchange [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][vc_column_text]

“This was a really interesting, thought provoking, relevant and empowering session. I really appreciated the knowledge and the care taken to pull it together. Thank you!” – Participant – CEO

The RRR team consists of specialists and facilitators in freedom of expression, artistic risk and ethical fundraising alongside Artistic Director/CEO hosts who are committed to asking the difficult questions of our time:[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”103264″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Julia Farrington has specialised in artistic freedom, working at the intersection between arts, politics and social justice, since 2005. She was previously Head of Arts (at Index on Censorship (2009 – 2014) and continues her pioneering work on censorship and self-censorship as Associate Arts Producer. From 2014 – 2016, Julia was head of campaigns for Belarus Free Theatre. She now works freelance and is a member of International Arts Rights Advisors (IARA), facilitator for Arts Rights Justice Academy and Impact Producer for Doc Society, promoting documentary film as a powerful advocacy tool.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”103265″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Diane Morgan is the Director of nitroBEAT and a consultant/producer. She works in collaboration with artists, leaders and organisations to support (and merge) artistic risk taking and social engagement ideas, practices and approaches. Previous roles include; Project Manager for the Cultural Leadership Programme, Decibel lead for Arts Council West Midlands and Head of Projects at Contact Theatre, Manchester.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”103266″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Helen Jenkins is a consultant for Cause4, a social enterprise that supports charities, social enterprises and philanthropists to develop and raise vital funds across the arts, education and charity sectors. She has over 20 years experience of working across all fundraising disciplines in senior management and at Board level. Helen has helped organisations nationally and internationally to achieve fundraising targets and retain their ethics within challenging financial climates.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Fees

£45 for individuals from organisations with an annual turnover of over £500K.

£80 for two individuals from organisations with an annual turnover of over £500K

£25 for individuals from organisations with an annual turnover of over £250-500K

£40 for two individuals from organisations with an annual turnover £250-500K

Bursaries

Diversity and equality are essential to both the dialogue and learning around artistic risk-taking and for stronger a cultural sector. The programme is actively seeking to be fully representative of, reflect, and to meet the needs of the arts and cultural community across; gender, race, disability, sexual orientation, religion and class.

In order to respond to existing under-representation we are offering a limited number of bursaries to cover the training session fee for BAME and disabled CEO/Artistic Directors, Chairs, individual Board Members and Senior team members, and individuals from organisations with an annual turnover of under £250k who are currently living and working in England.

To apply for a bursary please write to: [email protected] with a short description of your organisation and why you would like to attend this session. Deadline: Friday 9 November.

Access

We aim to provide an inclusive environment and will work with individual participants to make sure we can meet your access needs, such as providing support workers or British Sign Language interpreters or preparing programme materials in alternative formats. Our experienced facilitators aim to be as flexible as possible in order to make the programme work for your particular needs. For access queries please write to [email protected][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Enough is Enough is a play formed as a gig, tells the stories of real people about sexual violence, through song and dark humour. It is written by Meltem Arikan, directed by Memet Ali Alabora, with music by Maddie Jones, and includes four female cast members who act as members of a band.

Alabora has always been fascinated by the notion of play and games, even as a child. “I was in a group of friends that imitated each other, told jokes, made fun of things and situations,” he says. The son of actors Mustafa Alabora and Betül Arım, he was exposed early on to the theatre. In high school, Alabora took on roles in plays by Shakespeare and Orhan Veli. He was one of the founders of Garajistanbul, a contemporary performing arts institution in Istanbul.

For Alabora, ludology — the studying of gaming — is not merely about creating different theatrical personalities and presenting them to the audience each time. Rather, it is about creating an alternative to ordinary life — an environment in which actors and members of the audience could meet, intermingle and interact. For those two hours or so, participants are encouraged to think deeply about and reflect upon their own personal stories and the consequences of their actions.

“I think I’m obsessed with the audience. I always think about what is going to happen to the audience at the end of the play: What will they say? What situation do I want to put them in?” the Turkish actor says “It’s not about what messages I want to convey. I want them to put themselves in the middle of everything shown and spoken about, and think about their own responsibility, their own journey and history.”

“It’s not easy to do that for every audience you touch. If I can do that with some of the people in the audience, I think I will be happy,” Alabora adds.

It is this desire to create an environment in which the audience is encouraged to take part, to reflect, to think that Alabora brought to Mi Minör, a Turkish play that premiered in 2012. Written by Turkish playwright Meltem Arıkan, it is set in the fictional country of “Pinima”, where “despite being a democracy, everything is decided by the president”. In opposition to the president is the pianist, who cannot play high notes, such as the Mi note, on her piano because they have been banned. The play encouraged the audience to use their smartphones to interact with each other and influence the outcome.

Alabora explained the production team’s motivation behind the play: “At the time when we were creating Mi Minör, our main motive was to make each and every audience if possible to question themselves. This is very important. The question we asked ourselves was: if we could create a situation in which people could face in one and a half hour, about autocracy, oppression, how would people react?”

The goal wasn’t to “preach the choir” or convey a certain message about the world. It was to encourage the audience not be complacent. “Would the audience stand with the pianist, who advocates free speech and freedom of expression, or would they side with the autocratic president?” Alabora asks.

Alabora considered was how people would react when faced with the same situation in real life. “They were reacting, but was it a sort of reaction where they react, get complacent with it and go back to their ordinary lives, or would they react if they see the same situation in real life?”

On 27 May 2013, a wave of unrest and demonstrations broke out in Gezi Park, Istanbul to protest the urban development plans being carried out there. Over the next few days, violence quickly escalated, with the police using tear gas to suppress peaceful demonstrations. By July 2013, over 8,000 people were injured and five dead.

In the aftermath, Turkish authorities accused Mi Minör of being a rehearsal for the protests. Faced with threats against their lives, Arikan, Alabora and Pinar Ogun, the lead actress, had little choice but to leave the country.

But how could a play that was on for merely five months be a rehearsal for a series of protests that involved more than 7.5 million people in Istanbul alone? “You can’t teach people how to revolt,” Alabora says. “Yes, theatre can change things, be a motive for change, but we’re not living in the beginning of the 20th century or ancient Greece where you can influence day-to-day politics with theatre.”

The three artists relocated to Cardiff, but their experience did not prevent them from continuing with the work they love. They founded Be Aware Productions in January 2015 and their first production, Enough is Enough, written by Arikan, told the stories of women who were victims of domestic violence, rape, incest and sexual abuse. The team organised a month-long tour of more than 20 different locations in Wales.

“In west Wales, we performed in a bar where there was a rugby game right before – there was already an audience watching the game on TV and drinking beer,” Alabora says. “The bar owner gave the tickets to the audience in front and kept the customers who had just seen the rugby game behind.”

“After the play, we had a discussion session and it was as if you were listening to the stories of these four women in a very intimate environment,” he adds. “When you go through something like that, it becomes an experience, which is more than seeing a show.”

After each performance, the team organised a “shout it all out” session, in which members of the audience could discuss the play and share their personal stories with each other. One person said: “Can I say something? Don’t stop what you are doing. You have just reached out one person tonight. That’s a good thing because it strengthened my resolve. Please keep doing that. Because you have given somebody somewhere some hope. You have given me that. You really have.”

Be Aware Productions is now in the process of developing a new project that documents how the production team ended up in Wales and why they chose it as their destination.

“What we did differently with this project was that we did touring rehearsals. We had three weeks of rehearsal in six different parts of Wales. The rehearsals were open to the public, and we had incredible insight from people about the show, about their own stories and about the theme of belonging,” Alabora shares.

Just like Mi Minor and Enough is Enough, the motivation behind this new project is to encourage the audience to think, to reflect on their own personal stories and experiences: “With this new project, I want them to really think personally about what they think or believe and where this sense of belonging is coming from, have they thought about it, and just share their experiences.” [/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner content_placement=”top”][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1536657340830-d3ce1ff1-7600-4″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

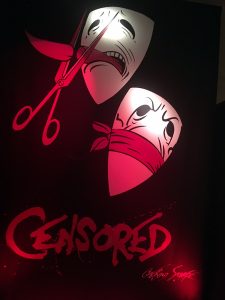

Censored by George Scarfe

Marking the 50th anniversary of the end of 300 years of theatre censorship, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition explores how restrictions on expression have changed.

The Theatres Act 1968 swept away the office of the Lord Chamberlain, which had the final say on what could appear on British stages.

“The 1968 Theatres Act was one of several landmark pieces of legislation in the 1960s, including the end of capital punishment, the legalisation of abortion, the introduction of pill, and the decriminalisation of homosexuality (for consenting males over the age of 21),” Harriet Reed, assistant curator at the V&A said.

Plays that had the potential to create immoral or anti-government feelings were banned by the Lord Chamberlain’s office or ordered to be edited. The exhibition includes original manuscripts with notes on what needs to be changed and letters from Lord Chamberlain explaining why the edits are required.

In the exhibition there are several pieces including a manuscript about the play Saved by Edward Bond. The play tells the story of a group of young people living in poverty and includes a scene in which a baby is stoned to death.

“When the Royal Court Theatre submitted the play to the censor, over 50 amendments were requested. Bond refused to cut two key scenes, stating ‘it was either the censor or me – and it was going to be the censor’. As a result, the play was banned,” Reed said.

Before the act was passed, playwrights got around the law by staging banned plays in “members clubs” which meant they could not be persecuted since it was private venue.

“The continued success of this strategy and the reluctance to prosecute made a mockery of the Lord Chamberlain’s powers and reflected the increasingly relaxed attitudes of the public towards ‘shocking’ material.

“The first night after the Act was introduced, the rock musical Hair opened on Shaftesbury Avenue in the West End. It featured drugs, anti-war messages and brief nudity, ushering in a new age of British theatre,” Reed said.

The exhibition changes from showcasing plays that were censored by the state to art, plays, movies, and music that are censored by society as a whole.

“It could be argued that a mixture of government intervention, funding/subsidy withdrawals, local authority and police intervention, self-censorship, and public protest now regulates what is seen on our stages,” she said.

Behzti, a play, and Exhibit B, a performance piece, were cancelled after protests by the public. The creators of both pieces were advised by the police to cancel their plays for health and safety reasons related to protests over the content.

Similarly, Homegrown, a play about radicalisation created by Muslims was shut down by the National Youth Theatre. The play was later published and a public reading was held.

On video, people involved in the UK arts industry such as Lyn Gardner, a theatre critic and Ian Christie, a film historian comment on what they believe to be censorship today. They cite art institutions that refuse to exhibit controversial material for fear of losing funding or facing public uproar. Julia Farrington, associate arts producer at Index on Censorship and one of the participants, calls this the “censorship of omission.”

The exhibition is capped by a piece by George Scarfe. The piece, the last work that attendees see, is a painting of two white masks on black cloth. The first one which is slightly higher and to the right of the second has it red tongue sticking out with the tip severed by a red scissors. The second one has a red cloth tied around it mouth. The word Censored is written in red and all caps below the two masks.

The painting is bold and the image of the tongue being cut off by scissors creates a “visceral” feeling. It depicts the two types of censorship that people now face– either talk and be violently censored or self-censor and never be heard.

“Many people would say that we are freer to express ourselves than ever before – with the boom of social media, we are able to communicate our thoughts and opinions on an unprecedented scale. This can also, however, invite more stringent and aggressive censorship from either the platform provider or under fear of criticism from other users,” Reed said.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534246236330-00e1ebeb-95f3-4″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]