10 Oct 2016 | mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Reports

Yeni Bir Şarkı Söylemek Lazım, Video, 2016, Işıl Eğrikavuk

Asena Günal is the program coordinator of Depo which is a center for arts and culture at Tophane, Istanbul. She is one of the co-founders of Siyah Bant, a research platform that documents censorship in the arts in Turkey.

“Is it just me? I don’t think so, but these days I’m in a state where I don’t know what to hold on to, what to do. I push myself to continue my work. Should I continue with art, or should I channel myself to more urgent things; that’s how suffocated I feel,” Hale Tenger, a prominent contemporary artist from Turkey, said in a roundtable discussion published in the Istanbul Art News.1 This pessimism reflects the general mood of artists and many other intellectuals in Turkey, a country that has experienced incidents so numerous in the past year that they could fill decades.

Since July 2015, almost 300 people have been killed and thousands wounded in various attacks by IS and the Kurdistan Freedom Eagles (TAK). After the elections in June 2015, in which the Kurdish party passed the 10% threshold and AKP lost its single party position, president Erdoğan pushed for another election. In November 2015, the AKP won the election and ended the peace process with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The government put severe limitations on the Kurdish and pro-peace opposition. A total of 2,212 academics, who signed a petition to condemn the state violence in the southeast of Turkey, have been targeted by Erdoğan, received threats, have been faced with criminal and disciplinary investigations, and four of them were detained and jailed for about a month. A growing number of academics have been dismissed or suspended, some were forced to resign and had to leave the country. Almost two thousand lawsuits have been filed against people alleged to have insulted the president online or offline.2

In January 2016, two members of the art community were arrested and then sued for participating in the peaceful demonstration “I am Walking for Peace” in Diyarbakır. The march was organised to protest state violence in the Kurdish region and ask for the restarting of the peace process. Artists Pınar Öğrenci and Atalay Yeni were arrested and then released conditionally. Their court cases still continue.

The impact of the recommencement of the war has made itself felt in various fields and ways. The cancellation of the exhibition “Post-Peace” in February 2016 shows the difficulty of expressing critical views on state policies. The exhibition curated by an Amsterdam-based curator Katia Krupennikova was cancelled by the institution Aksanat just five days before the opening, with the director citing the rising tension and the mourning after another bombing in Turkey as the reason. Given that other events went on as scheduled, many thought one of the video works in the exhibition, critical of the dirty war policies of the Turkish state against the Kurdish guerilla was considered risky by Aksanat.3 This was one of the incidents in which the state itself did not act, and actors in the artistic community took on this role. It created a discussion in the art scene about how to struggle in times of repression.4

Ayhan ve ben (Ayhan and me) from belit on Vimeo.

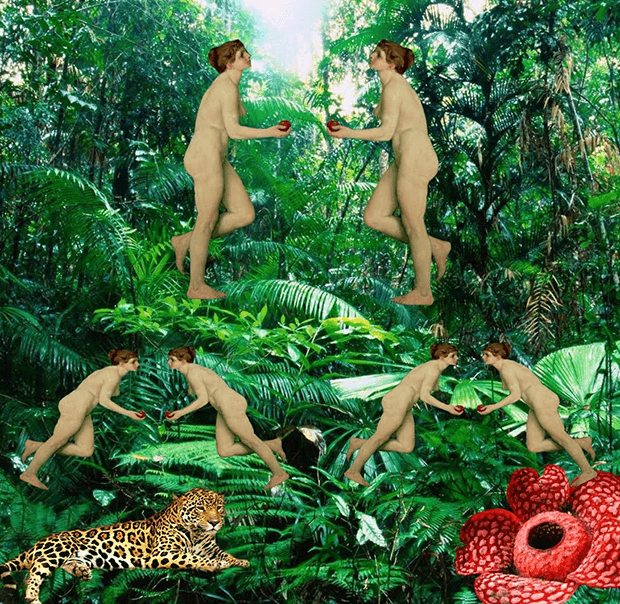

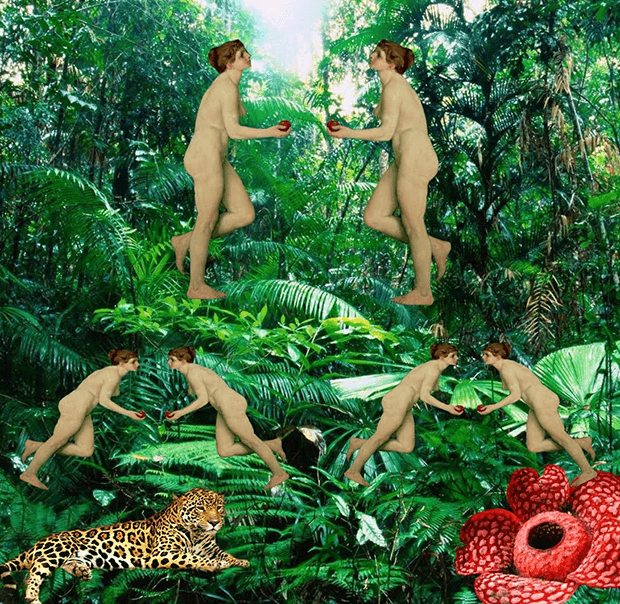

In April 2016, the screen of the public art project YAMA on a hotel roof was shut down by the Istanbul municipality on the basis of an anonymous complaint, claiming that the work of artist Işıl Eğrikavuk, a video animation, projecting the slogan “Finish up your apple, Eve!”, insulted religious sensibilities. When pressed, the municipality cited “visual pollution” as the reason for discontinuing the screening. This turn illustrates a strategy by the national and local government to legitimise their acts of censorship as purely procedural and administrative actions. After Eğrikavuk made a statement, YAMA’s curator Övül Durmuşoğlu declared the project’s support for the artist. Durmuşoğlu organised a meeting to discuss the case and invited Egrikavuk, legal consultants and people from the art scene. In the following days, Eğrikavuk did a performance based on this restraint. Both the meeting and the performance attracted a wide audience.

Even before the coup attempt of 15 July, there was such an atmosphere where people were worried about terrorist attacks, human rights violations, and limitations on freedom of expression. The coup attempt left 246 citizens and 24 coup planners dead and a nation deeply traumatised. The Gülen movement is accused of being behind the last coup attempt. The coup attempt was followed by a State of Emergency which allowed the cabinet under the chairmanship of the president to issue decrees that have the force of law.5 Unsurprisingly, Erdoğan has been using the attempt as an opportunity to eliminate critical voices.

In the five days between the coup attempt and the declaration of State of Emergency on 20 July, many festivals, biennials and concerts were postponed or cancelled by their organisers. The Sinop Biennial (Sinopale) was postponed “due to recent events in Turkey”, the One Love Festival was cancelled “due to availability problems on the schedules of artists and groups”, many concerts of the Istanbul Jazz festival including a performance by Joan Baez was cancelled6, Muse cancelled its concert“due to recent capricious events” and Skunk Anansie did the same “in light of the recent extraordinary events”. One issue of the satirical magazine Leman was banned as it suggested that both soldiers and civilians involved in the country’s recent unsuccessful coup were pawns in a larger game.

After the coup attempt, Erdoğan called the people to “Democracy Watch”-meetings. The biggest and final meeting, was the one at Yenikapı on 7 August 2016.7 Erdoğan invited popular figures, like singers, actors, and actresses to join the meeting. Pop singer Sıla announced on social media that although she was against the coup she would not be part of such a “show” and would not participate in the big meeting in Yenikapı. Sıla was the only figure brave enough to make such a declaration and not step back. But this resulted in the cancellation of her concerts in five different cities. Many people supported her by sharing her music videos and their own photos with an album of Sıla online.

Theatre actor Genco Erkal’s company “Dostlar Tiyatrosu” was banned from performing a play based on the writings of Turkish communist poet Nazim Hikmet and Bertolt Brecht. It was going to be performed in the garden of Kadıköy High School but the school cancelled the contract due to security reasons. It was obvious that security was not the issue and the school was under pressure from the Ministry of Education because of Genco Erkal’s critical stance. After protests of the theater company and members of the main opposition party (CHP), who brought the case to the Parliament, the Governorate lifted the ban.

Municipal and state theaters have been under a tight grip for some time and there have been ongoing discussions about privatisation of these institutions. The State of Emergency not only aimed at Gülenists who were accused of being part of the planning of the coup but also many artists with apparent oppositional stance were affected. On 1 August, the Istanbul Municipality fired 20 people, including director Ragıp Yavuz, actor Kemal Kocatürk, and actress Sevinç Erbulak from the Municipal Theatre based on the decree law number 667 which was announced after the declaration of the State of Emergency. They were not even granted an explanation for why they lost their jobs, but only received a vague reference to supposedly having failed “the evaluation criteria”8. Obviously, they did not have any connection with coup plotters. Eleven of them have been reinstated in their former positions.

Besides bans and purges, the State of Emergency has enabled the government to re-regulate the organisational structure of the state. A new law that would bring the privatisation of State Theatre, State Opera and Ballet, Atatürk Cultural Center, and Turkish Historical Society was discussed in Parliament. Many people from the field of theatre, opera and ballet expressed their concern that the State of Emergency might be utilised to bring privatisation after years of discussion on instating an independent arts council.

It is now common for the members of the ruling party to randomly target artists, writers, or academics in order to intimidate wider cultural milieu. A recent example is from the field of contemporary arts: In September 2016, an AKP MP Bülent Turan targeted the curator of the Çanakkale Biennial Beral Madra and called on the Çanakkale Municipality (run by CHP) not to work with her. The accusation was being critical of Erdoğan, and hence -so the argument went further- being “pro-coup”. Madra became a target because of her critical tweets and Facebook posts. Being critical of Erdoğan has long been risky but now it is associated with being “pro-coup”. Beral Madra withdrew from her position as to not put the Biennial at risk. Then the organising institution announced that the biennial would be cancelled altogether. They were saddened by the current political atmosphere, which did not place art as a primary point of concern. The CHP-run municipality and many people from the art scene expressed concern over the cancellation, highlighting instead the potential of art to counter the authoritarian discourse of AKP and expressing their wishes for the Biennial to go ahead as planned.

Despite this rising authoritarianism and the pessimistic atmosphere, Turkey’s culture and art scene will continue its struggle. Last week there were many openings in different galleries around Istanbul and almost all of them were crowded. People from the art scene are in need of each other more than ever, aware of the vital importance of solidarity in times of hardship. Film, music, dance and performance festivals started to take place, their posters filling the streets. So I would like to finish with another quote from the same issue of Istanbul Art News, by Deniz Artun,9 the director of Ankara Galeri Nev, as I tend to share its optimistic sentiment: “I guess that art history has shown us time and again just how deep the traces left by exhibitions, artworks, artists emerging with ‘pertinacity’ will be; not those amidst freedoms and prosperity, but those coming forth among fears and uncertainties that are burdensome for all of us.”

- September 2016, no. 34.

- Although many have been dropped after the attempted coup d’état in a show of good will they nonetheless can be said to have had a chilling effect on oppositional voices.

- See https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/05/75504/ for the open letter of belit sağ, the artist of that particular video work, and the artists’s response to the cancellation. Sara Whyatt elaborates the case in detail, http://artsfreedom.org/?p=11374.

- Özge Ersoy discusses this incident in terms of the different approaches to responsibility, transparency, sensitivity, institutional self-censorship, and institutional sustainability. See her report on the relationship between artists, curators, and institutions in the context of artistic freedom in Turkey: http://www.siyahbant.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/SiyahBant_Arastirma_KuratoryelPratikler-1.pdf.

- According to the Turkish Constitution, the Council of Ministers, which is led by the President, can declare a State of Emergency based on “widespread acts of violence aimed at the destruction of the free democratic order.” It must be approved by Parliament and allows the ministers to pass decrees that have the force of law, although they can be overruled by Parliament. It gives the state the right to derogate certain rights, including freedom of movement, expression and association, during times of war or a major public emergency.

- Joan Baez gathered reactions from Turkey with her statement that “I’m not sure I’ve seen anything like the immense and unpredictable danger which presents itself in today’s Turkey”. Istanbul Jazz Festival Director Pelin Opçin expressed her disappointment as Baez made them feel alone and punished by way of isolation: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-fans-let-down-by-joan-baez-remarks.aspx?pageID=238&nID=101923&NewsCatID=383

- Two opposition parties (CHP and MHP) were invited but the Kurdish opposition party (HDP) was not, showing the problematic character of the rhetoric of “democracy” and “national unity”.

- “As well as not being able to get an answer as to who, on what criteria judged our performance we could not reach any official explanation for our dismissal”, stated the theatre actors; https://twitter.com/oyuncusendika/status/763749835094822912?lang=tr

- September 2016, no. 34.

More about the arts in Turkey:

Belit Sağ: Refusing to accept Turkey’s silencing of artistic expression

Life is getting harder for objective journalists in Turkey, says cartoonist sued by Erdogan

Turkey: Artistic freedom and censorship

Turkey: Artists engaged in Kurdish rights struggle face limits on free expression

21 Sep 2016 | Magazine, mobile, News and features, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016 Extras, Youth Board

In the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, The Unnamed: Does anonymity need to be defended?, Index’s contributing editor for Turkey, Kaya Genç, explores anonymous artists in Turkey. In the piece the artists discuss how vital anonymity is in allowing them to complete their more controversial work. The Index on Censorship youth advisory board have taken inspiration from this piece for their latest task, in which they investigate anonymous art around the world.

Keizer by Constantin Eckner

Ants feature in Keizer’s work to sybolise “the forgotten ones, the silenced, the nameless, those marginalised by capitalism”. Image: Keizer

Prior to the January 25 Revolution political street art was anything but common in Egypt, yet it has proliferated in public spaces in the aftermath of the revolution. One of the most productive street artists in Cairo is Keizer, who has gained popularity and notoriety in recent years. Like Banksy and other street artists, he uses the well-known stencil technique to empower his fellow countrymen, and people in general, with his thought-provoking work. He likens people to ants, which are featured in most of his graffiti. Keizer explains on his Facebook account that the ant “symbolises the forgotten ones, the silenced, the nameless, those marginalised by capitalism. They are the working class, the common people, the colony that struggles and sacrifices blindly for the queen ant and her monarchy.”

Asked about the reason for protecting his identity, Keizer said: “I am very concerned over my safety and the repercussions of street art which I’ve already had a taste of, especially with this current regime. Including death threats,

Egyptian street artist Keizer has gained popularity in recent years. Image: Keizer

my twitter account was hacked twice. In the past five years of working on the street I’ve been caught once. I came out of it with a few bumps and bruises, nothing major. I consider myself lucky that I came out one day later.

“You can imagine that being caught here is very different than being caught in Europe. There is no proper procedure and that makes you a victim of the person handling you, and the uncertainty of what comes next. Graffiti is a grey area here, they don’t have any definition or classification for it in the books, so they make it up as they go along, taking you for the fear ride. It’s all under vandalism, so they can make it look small or escalate it to exaggerated levels. For instance, you can be dubbed as a political traitor; it can be considered racketeering; they can glue your name to any political movement unpopular with the people…etc.”

Tall walls, low profiles: Icy and Sot by Layli Foroudi

Icy and Sot describe themselves as stencil artists from Tabriz, Iran. As for their identities, they reveal only that they are brothers, born in 1985 and 1991. Their work is created under pseudonyms in countries around the world, including Iran, USA, Germany, Norway, and China, on legal and illegal walls as well as in galleries.

The anonymous duo, who paint on themes like human rights, censorship, and justice, say that charges against artists in Iran make going public risky.

“Pseudonyms help us to keep a low profile,” the brothers explained in an interview with ArtInfo, “Being arrested in Iran is completely different, because they charge you with crimes that you have not even committed, like Satanism or political crimes.”

Their work often uses striking human faces in black and white to make statements about politics and the environment, to call for peace, and to direct messages at the government of Iran. In 2015, Icy and Sot used their art to protest for freedom of expression in Iran, prompted by the arrest and 18-month imprisonment of Atena Farghadani, an Iranian artist who was detained for publishing a cartoon that satirised the Iranian government as animals. In solidarity, they stenciled a tribute piece depicting Farghadani with a backdrop of protesters on a wall in Brooklyn.

Maeztro Urbano’s fight to change a criminal image by Ian Morse.

In the most recent data, Honduras has the highest homicide rate in the world, with 84 intentional homicides per 100,000 people in 2013. The prominence of drug trafficking and ubiquity of poverty does not improve its reputation.

To some Hondurans, their country’s international image has done nothing but hurt citizen’s attempts to improve daily life in the country’s bustling cities and lively cultural centers. Maeztro Urbano and his friends became the face of an urban street art project to disrupt the atmosphere of crime and reveal another side of the country outside of the headlines.

His projects range from adjusting street signs promoting gender equality to vandalising billboards with corrupt politicians, to wall graffiti showing the effect of violence on children. Working his day shifts in the advertising industry, Maeztro Urbano said he wants to contribute more to his country than proliferating consumerism.

“Change should start within society. With each individual,” El Maestro – as he is also called – told The Creators Project. “To have respect for the lives of others, to respect the right to sexual diversity, to a better education.”

“If we don’t change that as a society and as individuals, we will never be able to change as a country.”

Assailants in Honduras have not been very hospitable to those reporting on crime or those wishing to express their identity. Faced with police harassment and shootings from unknown attackers, Maeztro Urbano chooses to wear a mask while he works to spread messages of hope around the country.

Bleeps.gr: Over a decade of political artivism in Athens by Anna Gumbau.

Bleeps.gr is one of Greece’s most prominent street artists, having painted murals on the streets of Athens for over 10 years. Image: Bleeps.gr

“I have been radically oriented to the political discourse, utilising the public sphere, and I am not afraid or discouraged”, Bleeps.gr, one of the most prominent Greek street artists, told Index.

Bleep.gr has been designing murals, that are mostly critical of the austerity policies imposed to Greece, on the streets of Athens for over 10 years. The Greek social turmoil has had a strong influence on his artwork, not only in his scenes, but even in his methods. “I buy very cheap materials and can’t afford those impressive equipment to create a mural”, he said in an interview with Street Art Europe.

Bleeps.gr chooses to use a pseudonym as an attempt to challenge “the institutionalised perception of the identity”, he told Index. While he is not afraid of the state authorities, he points at art institutions, such as galleries, exhibitions and festivals, who reject and exclude his art. “Most of the censorship I have received has come from other artists, especially the ones related to systemic initiatives, who in the past years have removed all of my works from the city center” he said. Greek political street artists often suffer from the exclusion of art galleries and exhibitors; in the summer of 2013, the CRISIS? WHAT CRISIS? street art festival in Athens, which celebrates the value of street art in the current political happenings, invited 20 artists from different European countries but failed to invite any Greek artists.

Nevertheless, Bleeps.gr stresses the fact that the internet “has provided a virtual field of allocation”, and most of the political street art discourse happens there.

Bleeps.gr highlights the mechanisms of such institutions to “absorb street artists” and make them become part of the art “business”, adding: “the majority of them nowadays serve gentrification policies and turn policies and turn political art into a spectacle for tourist pleasure”.

King of Spades by Sophia Smith-Galer.

When it comes to anonymous artists, the art tends to speak far louder than any speculation into the artist themselves. This anonymous artist in Lebanon is no Arab Banksy that lurks tantalisingly close to the limelight; this artist could quite literally be anyone, and the lack of anybody claiming the piece as their own is revelatory of the grave reality of artists in developing countries that test the patience of despots and tyrants.

Despite its tired and no longer relevant label “Paris of the Middle East”, even the dazzlingly artistic city of Beirut, Lebanon, can’t quite get away with hanging something like this banner, depicting the late Saudi Arabian monarch King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz as a brutal King of Spades. Shortly after its creation in 2013, the Lebanese state prosecutor ordered an investigation to reveal the source of these posters after complaints from Saudi Ambassador Ali Awad Asiri.

It seems that nobody got caught, and nor do I particularly want to dwell on what would have happened to the artist if they had. But in the Middle East, such a daring artistic expression must be forbidden fruit in a region of gagged political artistry; demonstrated no better than in this mysterious artist who gambled with the assumed impunity of that gentleman with the bloodied scimitar.

Dede Bandaid by Shruti Venkatraman.

One of Dede Bandaid’s most well known works, a missile target painted in the middle of a large car park, a reference to the Gaza conflict in 2014. Image: Dede Bandaid / Wikicommons

Dede Bandaid is an anonymous Israeli artist who has added colour to Tel Aviv’s streets with thought provoking and politically relevant street art. His artistic career began in 2000 during his compulsory military service, and most of his earlier pieces demonstrated a clear anti-establishment sentiment. His more recent works, following the end of his stint in the military, aim to communicate social and political messages. One of his most well known works is a missile target painted in the middle of a large car park, a reference to the Gaza conflict in 2014.

Dede enjoys using public spaces as a canvas as this approach allows freer and more controversial expression, while also being accessible to and viewable by a larger audience especially when the street art is photographed and its images are circulated online. He also makes use of traditional symbols of peace, like the white dove, and frequently incorporates Band-Aids that represent healing and remedy in his artwork, with “Bandaid” being the pseudonym he signs on all his pieces. Over time, Dede’s style has evolved from stencilling to free-hand painting and collage and he interestingly also exhibits certain pieces in galleries across the world.

Cabbage Walker in Kashmir by Niharika Pandit.

A pheran-clad man walks around with a cabbage on a leash in the neighbourhoods of Srinagar, Kashmir. This performance act that he presents is inspired by Chinese artist Han Bing’s “Walking the Cabbage” social intervention work. While Bing chose to walk the cabbage to reflect on the changing values in the Chinese society, where once cabbage was a subsistence food product but is now only embraced by the poor, in Kashmir, this anonymous artist aims to normalise the cabbage walking to show the absurdity of militarisation in the region. Both the performances employ cabbage as an element of satire to expose the irony inherent in what how elitism and militarisation come to be normalised in societies across the world.

The Kashmiri Cabbage Walker writes on his blog, “I as a Kashmiri am willing to recognise walking the cabbage as part of the Kashmiri landscape but I will never accept the check posts, the bunkers, the army camps, the torture centers, the barbed wire, the curfews, the arrests, the toxic environment of conflict and war, as part of the same.”

This performance artist chooses to remain anonymous as it helps in focusing on the message and not the messenger. The Kashmiri Cabbage Walker says that he represents all Kashmiri lives under militarisation thereby revealing the artist’s identity becomes unimportant here.

Cracked pavements in Budapest by Fruzsina Katona.

Anonymous volunteers have joined the satirial political party the Two-Tailed Dog party (MKKP) to paint cracked pavement on the streets of Budapest. Image: Fruzsina Katona

Anonymity does not necessarily mean that one is trying to hide his or her identity. Sometimes the identity of the person is utterly irrelevant. In Budapest, several anonymous volunteers are painting the streets of the city.

The pavement on the streets of the Hungarian capital are falling apart, ruining the image of the city and endangering those who walk on it. Authorities are known to do very little to fix the problem, but something had to be done. Hungary’s satiric political party, the Two-Tailed Dog party (MKKP) called for action and its artsy, anonymous volunteers started colouring the cracked pavement pieces resulting in dozens of cheerful spots across the city.

Unfortunately, there are some who find quarrels in a straw, and the police were called on the ad-hoc artists while they were peacefully decorating the pavement in a touristic neighbourhood. Now the volunteers are being prosecuted with vandalism.

But we still do not know their identity or how many of them are out decorating. All we know is that now we look at colourful patches of pavements while running our errands, instead of the sad and ugly cracked pavements.