24 Jul 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Campaigns, mobile

Khadija Ismayilova

Investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova declared her innocence at a pre-trial hearing, calling the charges against her poltically motivated.

Ismayilova, who has reported on corruption allegations involving the family of President Ilham Aliyev, is accused of embezzlement, tax evasion and abuse of power. Detained since December 2014, Ismayilova was originally charged with “incitement to suicide”, though that charge was later dropped.

The court barred members of the public, journalists, political figures and foreign diplomats, who had come to observe the proceedings, from entering the courtroom, Contact.az and Radio Free Europe reported.

Ismayilova’s trial was set to begin on 7 August.

“The decision to bar access to the public on the first day of Khadija’s trial underscores the capricious manner in which the government of President Ilham Aliyev is ruling Azerbaijan. Her’s is not the first spurious case aimed squarely at stifling critical voices in civil society. It’s vital that court officials hold the trial in a transparent manner”, Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship said.

In the past year major figures in Azerbaijan’s civil society have been silenced through pre-trial detentions and multi-year prison sentences.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the pre-trial hearing was part of the trial.

Recent coverage:

• Married political prisoners kept apart for 11 months, reunited in court

• Lawyers call for the release of Intigam Aliyev

• Azerbaijan: Silencing human rights

This article was posted on 24 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Jul 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

It should have been a happy day for Leyla and Arif Yunus. On 15 July, the couple — together for 37 years — saw each other for the first time in 11 months. The circumstances of their reunion, however, put a damper on what would otherwise have been a joyous occasion: it took place inside a glass cage, in a cramped courtroom in Baku, Azerbaijan. The human rights activists are on trial, on charges widely recognised to be politically motivated.

Initially scheduled for 13 July, but pushed back for unknown reasons, the Yunus’s pre-trial hearing came almost a year after they were first detained within days of each other in July and August of 2014. Leyla, director of the Peace and Democracy Institute, and Arif, a historian and researcher, have since been accused of an array of crimes, ranging from tax evasion and illegal business activities, to treason.

In the courtroom some 30 places were allocated to members of the public, who were stripped of their phones at the start of proceedings. Representatives from the German and EU embassies, as well as local journalists and NGOs were in attendance, according to Kati Piri, a Dutch member of the European Parliament who travelled to Baku for the trial. She estimated that more than half of the the crowd that had shown up, including other embassy delegations, did not manage to get into the room.

Piri told Index on Censorship that she was there to show support and solidarity for the couple, and that the European Parliament and the international community had not forgotten them and will continue to exert pressure.

“Even though the spotlight is no longer on Baku for the games, it will continue to be on when it comes to human right abuses,” she said, referring to the inaugural European Games, hosted with much fanfare by the Azerbaijani capital just weeks ago.

Proceedings lasted some 2.5 hours, and according to reports from inside the court, both Leyla and Arif looked pale and thinner. Leyla’s struggles with diabetes and Hepatitis C in prison have been well documented, but during the hearing she expressed worry in particular about her husband. Piri said Arif looked “much less strong and vivid than Leyla”. Their daughter Dinara told media in June that both her parents’ health has deteriorated since their arrest.

The van transporting Leyla and Arif Yunus (Photo: Kati Piri)

An appeal to the judges to allow Leyla to serve house arrest instead of imprisonment, was denied — as was every other motion filed by the defence, including a call for the case to be dropped altogether and a request that the couple be allowed to sit with their attorneys instead of the in the glass cages.

But Piri said Leyla seemed mentally very strong: “Mentally, they haven’t been able to break her.” Leyla took the opportunity, during a break in proceedings, to address the people in attendance, and according to Contact.az, she refused to stay silent even when the judge ignored her request to speak. “You are depriving me of the right to speak… I know that it is a false trial, but you have to give me an opportunity to speak…” she reportedly said.

The arrest of the couple in July and August 2014, was the first move in a crackdown by the regime of President Ilham Aliyvev, which has seen some of Azerbaijan’s most celebrated critical and independent voices arrested and sentenced on spurious, and frequently suspiciously similar charges, often relating to white-collar crime. Over the past few months, pro-democracy campaigner Rasul Jafarov has been handed down a 6.5 year sentence, while human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev and journalist Seymur Hezi have been jailed for 7.5 and five years respectively. Award-winning investigative reporter Khadija Ismayilova is due in court on 22 July.

Leyla and Arif Yunus’s next hearing is scheduled for 27 July. While Piri remains hopeful of a positive outcome for the couple, she is afraid “it will not depend on the judges, but on politicians what will happen in this case”.

This article was posted on 15 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Jun 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, News

Rahim Haciyev, editor of Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq, holds up a copy at the 2014 Index awards (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Index award-winning newspaper Azadliq, widely recognised as one of the last remaining independent news outlets operating inside the country, is facing imminent closure. This comes amid an ongoing crackdown on critical journalists and human rights activists in Azerbaijan, and as the country is hosting the inaugural European Games in the capital Baku.

A statement from the paper, quoted Thursday on news site Contact, outlined its “difficult financial situation”.

“If the problems are not resolved in the shortest possible time, the publication of the newspaper will be impossible,” it read.

“The closure of an independent media outlet like Azadliq, which Azerbaijani officials have suffocated over the past two years, flies in the face of repeated assurances from President Ilham Aliyev that his government respects press freedom. The fact that this financial crisis is occurring during the Baku European Games just underlines the shameful disregard that the Azerbaijani government has for freedom of expression,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

Azadliq has long faced an uphill battle to stay in business. Thursday’s statement merely detailed the latest development in a serious financial crisis, brought about at the hands of Azerbaijani authorities.

In July 2014, Azadliq was forced to suspend print publication. Editor Rahim Haciyev told Index that the government-backed distributor had refused to pay out the some £52,000 it owed the paper, which meant it could not pay its printer.

The paper has also seen its finances squeezed through being banned from selling copies on tube stations and the streets of Baku, and being slapped with fines of some £52,000 following defamation suits in 2013. The paper was also evicted from its offices in 2006 and its journalists have been repeatedly targeted by authorities. Seymur Hezi, for instance, was in January sentenced to five years in prison for “aggravated hooliganism” — charges widely dismissed as trumped up and politically motivated.

Azadliq — meaning “freedom” in Azerbaijani — has appealed to the public for help to stay afloat, urging “those who defend the freedom of speech in Azerbaijan” to join in the campaign to save the paper.

This comes after the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) condemned “the crackdown on human rights in Azerbaijan”. In a resolution adopted on Wednesday 24 June, PACE called on authorities to “put an end to systemic repression of human rights defenders, the media and those critical of the

government”.

This article was posted on 25 June, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

17 Jun 2015 | Azerbaijan News, mobile, News

Governments don’t really like coming across as authoritarian. They may do very authoritarian things, like lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro democracy campaigners, but they’d rather these people didn’t talk about it. They like to present themselves as nice and human rights-respecting; like free speech and rule of law is something their countries have plenty of. That’s why they’re so keen to stress that when they do lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners, it’s not because they’re journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. No, no: they’re criminals you see, who, by some strange coincidence, all just happen to be journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. Just look at the definitely-not-free-speech-related charges they face.

1) Azerbaijan: “incitement to suicide”

Khadija Ismayilova is one of the government critics jailed ahead of the European Games.

Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was arrested in December for inciting suicide in a former colleague — who has since told media he was pressured by authorities into making the accusation. She is now awaiting trial for “tax evasion” and “abuse of power” among other things. These new charges have, incidentally, also been slapped on a number of other Azerbaijani human rights activists in recent months.

2) Belarus: participation in “mass disturbance”

Belorussian journalist Irina Khalip was in 2011 given a two-year suspended sentence for participating in “mass disturbance” in the aftermath of disputed presidential elections that saw Alexander Lukashenko win a fourth term in office.

3) China: “inciting subversion of state power”

Chinese dissident Zhu Yufu in 2012 faced charges of “inciting subversion of state power” over his poem “It’s time” which urged people to defend their freedoms.

4) Angola: “malicious prosecution”

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Sean Gallagher/Index on Censorship)

Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan investigative journalist and campaigner, has for months been locked in a legal battle with a group of generals who he holds the generals morally responsible for human rights abuses he uncovered within the country’s diamond trade. For this they filed a series of libel suits against him. In May, it looked like the parties had come to an agreement whereby the charges would be dismissed, only for the case against Marques to unexpectedly continue — with charges including “malicious prosecution”.

5) Kuwait: “insulting the prince and his powers”

Kuwaiti blogger Lawrence al-Rashidi was in 2012 sentenced to ten years in prison and fined for “insulting the prince and his powers” in poems posted to YouTube. The year before he had been accused of “spreading false news and rumours about the situation in the country” and “calling on tribes to confront the ruling regime, and bring down its transgressions”.

6) Bahrain: “misusing social media

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

In January nine people in Bahrain were arrested for “misusing social media”, a charge punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison. This comes in addition to the imprisonment of Nabeel Rajab, one of country’s leading human rights defenders, in connection to a tweet.

7) Saudi Arabia: “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”

In late 2014, Saudi women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets, on charges including “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”.

8) Guatemala: causing “financial panic”

Jean Anleau was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing their money from banks.

9) Swaziland: “scandalising the judiciary”

Swazi Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu in 2014 faced charges of “scandalising the judiciary”. This was based on two articles by Maseko and Makhubu criticising corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

10) Uzbekistan: “damaging the country’s image”

Umida Akhmedova (Image: Uznewsnet/YouTube)

Uzbek photographer Umida Akhmedova, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, was in 2009 charged with “damaging the country’s image” over photographs depicting life in rural Uzbekistan.

11) Sudan: “waging war against the state”

Al-Haj Ali Warrag, a leading Sudanese journalist and opposition party member, was in 2010 charged with “waging war against the state”. This came after an opinion piece where he advocated an election boycott.

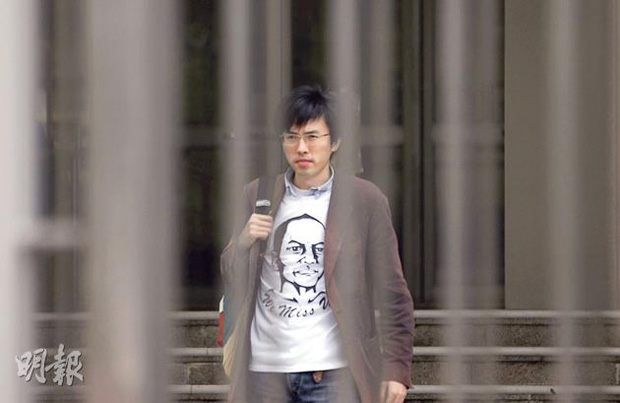

12) Hong Kong: “nuisance crimes committed in a public place”

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

Avery Ng, an activist from Hong Kong, was in 2012 charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place” after throwing a t-shirt featuring a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit.

13) Morocco: compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”

Rachid Nini, a Moroccan newspaper editor, was in 2011 sentenced to a year in prison and a fine for compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”. A number of his editorials had attempted to expose corruption in the Moroccan government.

This article was originally posted on 17 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org