19 Jan 2016 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, Statements

NGOs from the around the world call for the immediate release of prisoner of conscience Dr. Abduljalil al-Singace on his 300th day of hunger strike. Dr. al-Singace began his hunger strike in March 2015 as a response to police subjecting inmates at the Central Jau Prison to collective punishment, humiliation and torture.

Since 21 March 2015, Dr. al-Singace has foregone food and subsisted on water and IV fluid injections for sustenance. Days later, Jau prison authorities transferred him to the Qalaa hospital, where he is still being kept in a form of solitary confinement.

Dr. al-Singace’s family, who visited him on 7 January, state that the prison administration is controlling his treatment at Qalaa hospital, and has for five months continuously, denied his need for a physical checkup by his hematologist at Salmaniya Medical Complex.

According to Dr. al-Singace’s family, he is not allowed to walk outside. He remains isolated in the Qalaa hospital, and is provided only irregular contact with his family. He is frequently denied basic hygienic items including soap, and is not allowed to interact with other patients in the hospital.

Dr. al-Singace is a member of the Bahrain 13, a group of thirteen peaceful political activists and human rights defenders, including Ebrahim Sharif and Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, sentenced to prison terms for their peaceful role in Bahrain’s Arab Spring protests in 2011.

Dr. al-Singace was first arrested in August 2010 at Bahrain airport. He had just returned from a conference at the British House of Lords regarding human rights in Bahrain. Security forces detained Dr. al-Singace for six months, during which he was tortured, and released him in February 2011 during the height of protests. However, Dr. al-Singace was rearrested on 17 March 2011, after his participation in peaceful pro-democracy protests. In detention, officers blindfolded, handcuffed, and beat Dr. al-Singace in the head with their fists and batons. Officers threatened him and his family with reprisals.

On 22 June 2011, a military court sentenced Dr. al-Singace to life for attempted overthrow of the regime. Since then, he has been imprisoned in the Central Jau Prison, and has only recently received treatment for a nose injury sustained during torture. He has been denied treatment for a similar ear injury also sustained during torture since his incarceration.

In 2015, Dr. al-Singace was awarded the Liu Xiaobo Courage to Write Award by the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, and was named one of Index on Censorship’s 100 “free expression heroes” in 2016. He has long campaigned for an end to torture and political reform, writing on these and other subjects on his blog, Al-Faseela, which remains banned by Bahraini Internet Service Providers. Bahrain has become a dangerous place for those who speak out, with peaceful dissidents at risk of arbitrary arrests, systematic torture and unfair trial.

We, the undersigned NGOs, call on the government of Bahrain to immediately secure the release of Dr. al-Singace and all prisoners of conscience, and to provide all appropriate and necessary medical treatment for Dr. al-Singace.

Signatories:

Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Croatian PEN

Danish PEN

English PEN

European Center for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

FIDH, within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Ghanaian PEN

Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR)

Icelandic PEN

Index on Censorship

Italian PEN

Norwegian PEN

PEN America

PEN Bangladesh

PEN Bolivia

PEN Canada

PEN Català

PEN Center Argentina

PEN Center USA

PEN Centre of German Speaking Writers Abroad

PEN Eritrea in Exile

PEN Flander

PEN Germany

PEN International

PEN Netherlands

PEN New Zealand

PEN Québéc

PEN Romania

PEN South Africa

PEN Suisse Romand

Peruvian PEN

Reporters Sans Frontiers (RSF)

San Miguel PEN

Scholars at Risk

Scottish PEN

Serbian PEN

Trieste PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Zambian PEN

16 Dec 2015 | Awards, Events, mobile, Press Releases

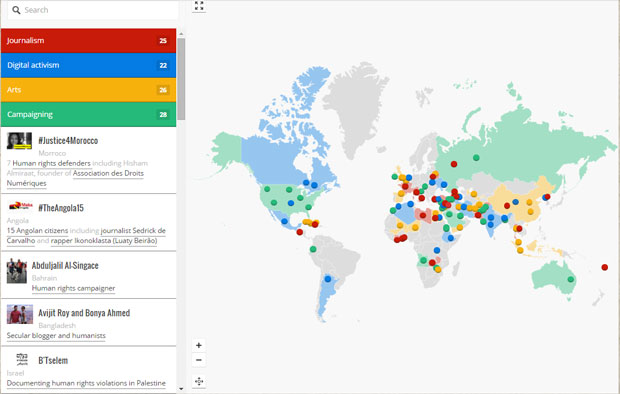

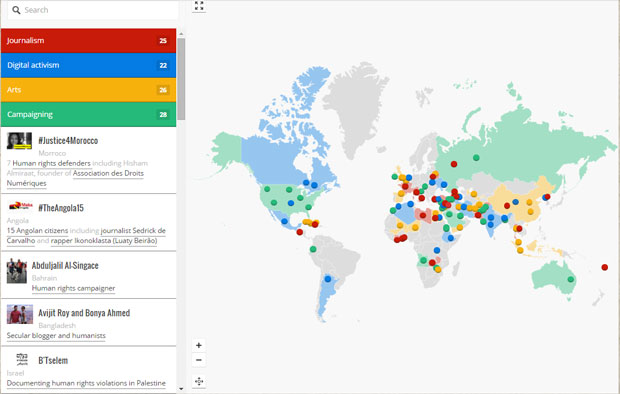

A graffiti artist who paints murals in war-torn Yemen, a jailed Bahraini academic and the Ethiopia’s Zone 9 bloggers are among those honoured in this year’s #Index100 list of global free expression heroes.

Selected from public nominations from around the world, the #Index100 highlights champions against censorship and those who fight for free expression against the odds in the fields of arts, journalism, activism and technology and whose work had a marked impact in 2015.

Those on the long list include Chinese human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang, Angolan journalist Sedrick de Carvalho, website Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently and refugee arts venue Good Chance Calais. The #Index100 includes nominees from 53 countries ranging from Azerbaijan to China to El Salvador and Zambia, and who were selected from around 500 public nominations.

“The individuals and organisations listed in the #Index100 demonstrate courage, creativity and determination in tackling threats to censorship in every corner of globe. They are a testament to the universal value of free expression. Without their efforts in the face of huge obstacles, often under violent harassment, the world would be a darker place,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

Those in the #Index100 form the long list for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards to be presented in April. Now in their 16th year, the awards recognise artists, journalists and campaigners who have had a marked impact in tackling censorship, or in defending free expression, in the past year. Previous winners include Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, Argentina-born conductor Daniel Barenboim and Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat.

A shortlist will be announced in January 2016 and winners then selected by an international panel of judges. This year’s judges include Nobel Prize winning author Wole Soyinka, classical pianist James Rhodes and award-winning journalist María Teresa Ronderos. Other judges include Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab, tech “queen of startups” Bindi Karia and human rights lawyer Kirsty Brimelow QC.

The winners will be announced on 13 April at a gala ceremony at London’s Unicorn Theatre.

The awards are distinctive in attempting to identify individuals whose work might be little acknowledged outside their own communities. Judges place particular emphasis on the impact that the awards and the Index fellowship can have on winners in enhancing their security, magnifying the impact of their work or increasing their sustainability. Winners become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given support for the year after their fellowship on one aspect of their work.

“The award ceremony was aired by all community radios in northern Kenya and reached many people. I am happy because it will give women courage to stand up for their rights,” said 2015’s winner of the Index campaigning award, Amran Abdundi, a women’s rights activist working on the treacherous border between Somalia and Kenya.

Each member of the long list is shown on an interactive map on the Index website where people can find out more about their work. This is the first time Index has published the long list for the awards.

For more information on the #Index100, please contact [email protected] or call 0207 260 2665.

25 Nov 2015 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Photographer Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi

Award-winning photographer Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi was sentenced on Monday, 23 November 2015, to 10 years in prison and had his nationality revoked, along with 12 others, after covering a series of demonstrations in early 2014. Security forces detained Al-Mousawi for over a year without trial or official charges, accused him of being a part of a terrorist cell and subjected him to torture. The undersigned NGOs condemn the government’s continued attacks on independent journalism, policy of media censorship and severe restrictions on freedom of expression in Bahrain.

Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi, a winner of 127 international photography awards, has been incarcerated since his arrest on 10 February 2014, when security forces raided his home in Duraz village. According to al-Mousawi’s father, a group of plainclothes masked policemen arrested Sayed Ahmed and his brother. The police provided no arrest warrant and confiscated al-Mousawi’s cameras and electronic devices. Al-Mousawi alleges that he was tortured during his detention and interrogation.

Al-Mousawi’s torture follows a pattern of abuse Human Rights Watch documented in a new report released on 24 November on the ongoing use of torture in Bahraini police detention and prison. Police disappeared and tortured al-Mousawi for five days, subjecting him to severe beatings on his genitals, electrocution and hanging from a door. For the duration of his disappearance, he was stripped naked and forced to stand for long periods of time. Officers did not allow a lawyer to accompany al-Mousawi when they transferred him to the Public Prosecutor. Courts renewed al-Mousawi’s pre-trial detention six times, and he spent over a year in prison without formal charges.

“Sayed al-Mousawi’s torture took place at a time when the UK has been increasing its spending on a ‘reform programme’ for Bahrain to bolster its institutions,” said Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy at BIRD. “It is becoming increasingly clear that this programme has failed. Torture is still systematic and unrelenting and the government has broken all promises of reform.”

During his extended detention, al-Mousawi continued to win international awards for his photography. In spite of this, the government accused him of giving SIM cards to “terrorist” demonstrators and taking photos of anti-government protests. As a result, Bahrain tried al-Mousawi under Bahrain’s vague anti-terrorism legislation. A judge later accused him and his brother of membership in a terrorist cell, which al-Mousawi continues to deny.

“Al-Mousawi’s case exposes Bahrain’s continued misapplication of its counterterrorism law to hide evidence of its human rights abuses,” said Husain Abdulla the Executive Director of ADHRB. “Taking photos of peaceful protestors is not a crime and Bahrain’s overreaction shows just how fearful the Bahraini government is of its own people.”

Bahrain’s continued arrest of journalists and photographers, who expose human rights violations, reflects a systematic campaign by the authorities to quell freedom of expression and the press. Bahrain is ranked 163 out of 180 in the 2015 World Press Freedom Index according to Reporters Without Borders. Last year, a Bahraini court also convicted another renowned photojournalist, Ahmed al-Humaidan to 10 years in prison under similar charges. Bahrain has revoked the citizenship of more than 130 individuals since 2012.

“Yet again the Bahraini government has wielded citizenship as a weapon of censorship against journalists,” said CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa program coordinator, Sherif Mansour. “We call on the Bahraini judiciary to overturn this disturbing sentence, recognize al-Mousawi’s citizenship, and free him immediately.”

We, the undersigned NGOs, call for the immediate release of Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi, and on Bahrain to end the criminalization of free speech and press. We also call on the UK government to suspend its spending on technical assistance to Bahrain, and on the US government to reinstate the ban on arms sales to the country, until systematic torture has been eradicated and restrictions on the enjoyment of internationally-codified human rights are lifted.

Sincerely,

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Index on Censorship

11 Nov 2015 | Bahrain, Middle East and North Africa, mobile, News

Ebrahim Sharif received a royal pardon before being rearrested three weeks later. He was photographed with his family during his brief release.

This is the second of two posts by Farida Ghulam, joined by her daughter Yara and son Sharif, describing the impact the Bahraini government’s crackdown on freedom of expression has had on the family. Ghulam is an advocate for freedom of speech, human rights and democracy. She has campaigned for women’s rights and is currently active in the push for democratic reforms in Bahrain. Her husband, Ebrahim Sharif, who is a former Secretary General of the National Democratic Action Society (WAAD), is currently in detention awaiting trial on charges of inciting hatred and sectarianism and calling for violence against the regime. In 2011, Ebrahim Sharif was arrested as Bahrain’s government moved to suffocate calls for democratic reforms during the Arab Spring. He was released by a royal pardon in June 2015 and rearrested three weeks later. He faces 10 years for expressing opinions in a speech marking the memory of a 16-year-old killed while protesting against Bahrain’s government. Part one: Freedom in Bahrain: “It’s like a dream, isn’t it?”

My husband’s first and second arrests, in 2011 and 2015 respectively, have inflicted painful changes on our lives as a family. Since then most of our conversations have revolved around visit schedules, notifications, updates, mistreatment or exaggerated body searches.

We wait anxiously for these visits only to feel that nothing was said because there wasn’t enough time. Not only is time scarce, but visits are always monitored by policewomen. There is no sense of privacy and the speed that one has to speak with to cover most news makes it like “quick reporting”. Cameras are always filming and must not be blocked by our seating. Phone calls are always monitored and have been cut many times because of a word or a piece of unwanted news. This leaves us with zero privacy.

After the second arrest, a video recorder became compulsory in the visitation room at all times, and it is turned on right before the visit starts. Additionally, prison guards physically monitor us by being present inside and outside of the room for the entire duration of the visit. Although the visiting arrangements and procedures are tight and irritating, we insist on using that precious time with Ebrahim because it is part of his stolen freedom.

In addition to the frustration we feel due to Ebrahim’s freedom being stolen by arresting him on false charges related to his freedom of expression, we are further irritated with the fact that our rights to privacy and freedom of expression are tied down during these visits and phone calls. They have stolen many years of Ebrahim’s life, our lives, and our time together.

Although we do not know when this cycle of government-induced revenge will end, we are all stronger and more determined than ever. We will never accept injustice and will continue fighting for Ebrahim’s freedom, for our rights, and the rights of the people of Bahrain.

Farida Ghulam

November 2015

Yara Ebrahim Sharif

Daughter of Farida Ghulam and Ebrahim Sharif

I was a normal 20-year-old college student at the University of Washington in Seattle. I had just completed my exams and spring break was a few days away. While meeting a friend for coffee, I received a call that would change my life forever: “Yara, was your father arrested? It’s all over Twitter!”

I immediately called my mother to confirm, but she didn’t answer, so I called my sister, Aseel, who works abroad. She picked up the phone half asleep as it was 3am there and had no clue what I was talking about. I called my mother back and, luckily, she picked up. As soon as she confirmed the arrest and detailed the manner in which my father, Ebrahim Sharif, was arrested, I told her to slow down so that I could write all the details down on my laptop to publish online.

I recorded how masked men with guns came over our fence at 2am on 17 March 2011, arrested my father without a warrant, mocked my mother and left no contact information with our family. I didn’t know if my writing would gain any traction online or if anyone would read it because I had about 50 followers on Twitter at that time. Overnight, the followers jumped to over 3,000, and that’s when it all began.

I had hoped that it would all pass by and my father would be released soon. A month went by, and we still had no idea where he was, who he was with or if he had been tortured or not. I was instructed to stay in the US by my family and advising professors, so I took the quarter off and spent it in a bubble of depression, only responding to reporters who contacted me for statements, but for the most part, it was just a never ending gut-wrenching feeling.

My hope of my father being released in a few weeks never came true. I came back to see him after his unjustified sentence during visitation hours. Things continued like this for more than four years. I graduated from university while my father was in prison. I moved back to Bahrain in 2013, started part-time work and moved abroad a year later for an exciting job. I had hoped my father would be there for these moments, for him to fly with and help me choose an apartment, help set up some IKEA tables just as we had with my sister when she moved for work.

I had hoped to make and enjoy breakfast in my new apartment with my family, just as we had done five years earlier for my sister. None of these things happened. I had to inform my dad about everything either over the phone or on steel chairs during monitored visits where he was separated from us behind an open window.

There were no real-time updates — the kind of updates children like to give their parents in person, the kind of updates any child would want to celebrate with their parents. There was no flying to Bahrain to surprise my parents at home. Instead, I was flying to Bahrain to visit my father during scheduled hours after being frisked by policewomen.

The biggest personal impact of having my father arrested was that he never got to see me grow up. I was studying for my bachelor’s degree between the ages of 18 to 21. My father was arrested when I was 20. I am 25 now. My father won’t recognise the person I have grown to be, and I can only blame the government of Bahrain.

He doesn’t know who I was during those years, and who I am becoming. He doesn’t know the real growth I’ve experienced because a one hour monitored visit with eight other family members surrounding you gives you no chance to really connect for more than a few minutes. My relationship with my father was stolen from me; I was robbed from sharing important milestones with him and I can’t wait for the day to share my life with him, to update him on all the years gone by.

It has not been an easy road for me, or for any of my family members. My sister is still waiting on her wedding day, despite being married for four years now. She refuses to have a wedding without a father to dance with. My brother has graduated and moved abroad as well, with my father missing those milestones too. My mother continues to fight for his right to be free and for the freedom of the many people of Bahrain that share the same fate behind bars. Despite these being difficult times, we know that our father’s conscience is clear. He is in jail because he stands on the right side of history — because he defends the less fortunate and speaks the truth. He is a man of courage and conviction, and we can learn a lot from him.

As my father said in his hearing in the Higher Court of Appeals on 5 June 2015: “They may imprison our bodies, but they will not be able to imprison our dream… a dream of freedom and dignity for our people.”

Sharif Ebrahim Sharif

Son of Farida Ghulam and Ebrahim Sharif

No one should ever wake up to a call in the middle of the night to hear that something terrible has happened to a loved one, but that’s exactly what I went through in my sophomore year of college when my father was arrested in Bahrain for daring to speak his mind.

A friend of mine at the University of Michigan woke me up with his call, and sounded a little tense and upset as he asked me if I had heard the news and if I was OK. I had no idea what he was talking about, and that’s when he told me my father had been arrested and no one knew where he was. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I felt like the walls were closing in on me, I couldn’t breathe, my heart was racing as I sat there in my dark dorm room, thousands of miles away from home, completely powerless to help.

My family was kept in the dark about my dad’s whereabouts for quite a while afterward. Occasionally there would be rumors that he had been spotted at some hospital or other receiving treatment, but that was all we had to go on. The feeling that my life was crashing down around me was with me every day, made worse by the fact that I still had lectures to attend, tests to take, projects to work on. I had to go about my life while my dad was missing. It was a soul crushing experience, having to force myself to put aside my fears and my worries and my sadness and work on that next calculus set or programming assignment. Over time, we got more details as to my dad’s whereabouts, and eventually he was allowed to call us; just hearing his voice was an incredible relief because it meant that he was alive.

My dad has been forced to miss the entirety of my adult life. I’m a very different person now than I was when I got that call all those years ago, and I’ve had to go through the process of becoming an adult with only infrequent windows of contact with him, usually lasting no more than 10 minutes every other week at most. He couldn’t even attend my graduation. With every major life event I went through I had to wait a week or more before I could tell him about it. Even when we did get to talk, I had to condense topics and prioritise because there just wasn’t enough time. Even then we were censored as there were topics we weren’t allowed to discuss over the phone, especially politics. Until his temporary release that lasted all of three weeks, the extent of my interactions with my dad as an adult were all through these little 10 minute windows, and occasionally longer visits when I was back home, where everything we said was being monitored. Not being allowed to even have a private conversation is insidiously oppressing — everything I say has to pass through a filter: “Can I say this? Will the monitors cut the call off? Am I OK with the Bahraini government knowing this?”

I am glad at the very least that my dad got to see my sisters and I as we are now, without any surveillance or prison walls separating us, for those three weeks that he was free. I want my dad back more than anything and am hopeful that he will be a full part of our lives again soon.

To learn more about Ebrahim Sharif, please visit https://freesharif.wordpress.com/ or follow us on twitter: @FreeSharif and Facebook