8 Jan 2016 | Belarus, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Turkey

The attacks on the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris in January set the tone for conditions for media professionals in 2015. Throughout the year, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom correspondents verified a total of 745 violations of media freedom across Europe.

From the murders of journalists in Russia, Poland and Turkey to the growing threat posed by far-right extremists in Germany and government interference in Hungary — right down to the increasingly harsh legal measures imposed on reporters right across the continent — Mapping Media Freedom exposed many difficulties media workers face in simply doing their jobs.

“Last year was a tumultuous one for press freedom; from the attacks at Charlie Hebdo to the refugee crisis-related aggressions, Index observed many threats to the media across Europe,” said Hannah Machlin, Index on Censorship’s project officer for the Mapping Media Freedom project. “To highlight the important cases and trends of the year, we’ve asked our correspondents, who have been carefully monitoring the region, to discuss one violation each that stood out to them.”

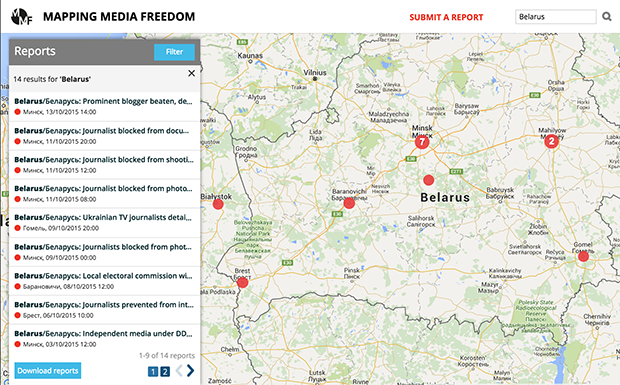

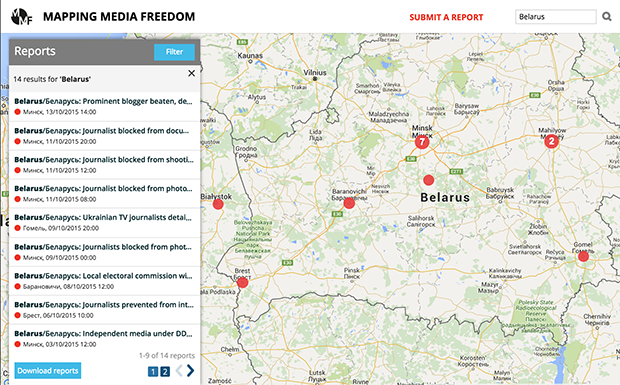

Belarus / 19 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

Journalist blocked from shooting entrance to polling station

“It demonstrates the Belarusian authorities’ attitude to media as well as ‘transparency’ of the presidential election – the most important event in the current year.” — Ольга К.-Сехович

Greece / 15 verified reports in 2015

Four journalists detained and blocked from covering refugee operation

“This is important because it is typical ‘attempt to limit press freedom’, as the Union wrote in a statement and it is not very hopeful for the future. The way refugees and migrants are treated is very sensitive and media should not be prevented from covering this issue.” — Christina Vasilaki

Hungary / 57 verified reports in 2015

Serbian camera crew beaten by border police

“These physical attacks, the harsh treatment and detention of journalists are striking because the Hungarian government usually uses ‘soft censorship’ to control media and journalists, they rarely use brute force.” — Zoltan Sipos

Italy / 72 verified reports in 2015

Italian journalists face up to eight years in prison for corruption investigation

“I chose it because this case is really serious: the journalists Emiliano Fittipaldi and Gianluigi Nuzzi are facing up to eight years in prison for publishing books on corruption in the Vatican. This case could have a chilling effect on press freedom. It is really important that journalists investigate and they must be free to do that.” — Rossella Ricchiuti

Lithuania / 9 verified reports in 2015

Journalist repeatedly harassed and pushed out of local area

“I chose it because I found it relevant to my personal experience and the fellow journalist has been the only one to have responded to my hundreds of e-mails — including requests to fellow Lithuanian journalists to share their personal experience on media freedom.” — Linas Jegelevicius

Macedonia / 27 verified reports in 2015

Journalist publicly assaults another journalist

“I have chosen this incident because it best describes the recent trend not only in Macedonia and my other three designated countries, Croatia, Bosnia and Montenegro, but also in the whole region. And that is polarization among journalists, more and more verbal and, like in this unique case, physical assaults among colleagues. It best describes the ongoing trend where journalists are not united in safeguarding public interest but are nothing more than a tool in the hands of political and financial elites. It describes the division between pro-opposition and pro-government journalists. It is a clear example of absolute deviation from the journalistic ethic.” — Ilcho Cvetanoski

Poland / 11 verified reports in 2015

Law on public service broadcasting removes independence guarantees

“The new media law, which was passed through Poland`s two-chamber parliament in the last week of December, constitutes a severe threat to pluralism of opinions in Poland, as it is aimed at streamlining public media along the lines of the PiS party that holds the overall majority. The law is currently only awaiting president Duda’s signature, who is a close PiS ally.” — Martha Otwinowski

Portugal / 9 verified reports in 2015

Two-thirds of newspaper employees will be laid off

“It’s a clear picture of the media in Portugal, which depends on investors who show no interest in a healthy, well-informed democracy, but rather in how owning a newspaper can help them achieve their goals — and when these are not met they don’t hesitate to jump boat, leaving hundreds unemployed.” — João de Almeida Dias

Russia / 37 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

Media freedom NGO recognised as foreign agent, faces closure

“The most important trend of the 2015 in Russia is the continuing pressure over the civil society. More than 100 Russian civil rights advocacy NGOs were recognized as organisations acting as foreign agents which leads to double control and reporting, to intimidation and insulting of activists, e.g., by the state-owned media. Many of them faced large fines and were forced to closure.” — Andrey Kalikh

Russia / 37 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

TV2 loses counter claim to renew broadcasting license Roskomnadzor

“It illustrates the crackdown on independent local media, which can not fight against the state officials even if they have support from the audience and professional community.” — Ekaterina Buchneva

Serbia / 41 verified reports in 2015

Investigative journalist severely beaten with metal bars

“It’s a disgrace and a flash-back to Serbia’s dark past that a journalist, who’s well known for investigating high-level corruption, get’s beaten up with metal bars late at night by ‘unknown men’.” — Mitra Nazar

Turkey / 97 verified reports in 2015

Police storm offices of Koza İpek, interrupting broadcast

“The raid on Bugün and Kanaltürk’s offices just days ahead of parliamentary elections was a drastic example — broadcasts were cut by police and around 100 journalists ended up losing their jobs over the next month — of how the current Turkish government tries to strong-arm media organisations.” — Catherine Stupp

Mapping Media Freedom

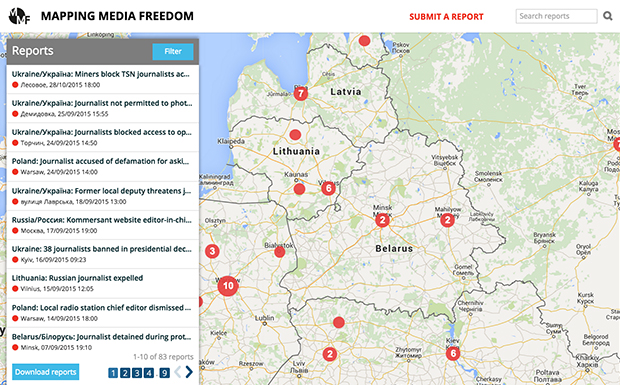

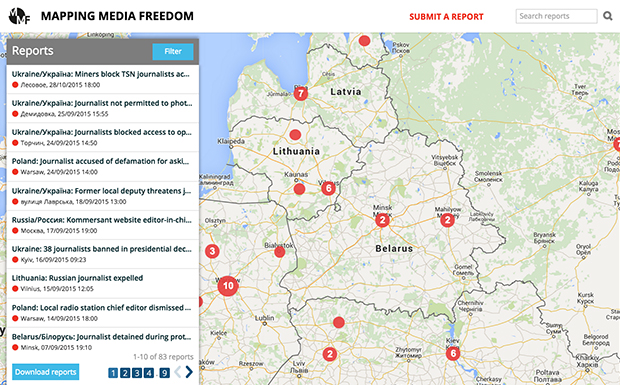

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

8 Dec 2015 | Belarus, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

Credit: Shutterstock / Fedor Selivanov

Miklos Haraszti, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Belarus, has called for reforms to the country’s laws and practices that for two decades have stifled freedom of expression.

“Critical opinion and fact-finding are curtailed by the criminalisation of content that is deemed ‘harmful for the State’; by criminal defamation and insult laws that protect public officers and the president, in particular, from public scrutiny; and by ‘extremism’ laws that ban reporting on political or societal conflicts,” Haraszti said in a 6 November statement.

Belarus anti-extremism law came into force in 2007. According to Article 14 of the Law On Countering Extremism, it is prohibited to publish and or disseminate extremist materials, even through the media. Information products propagandising extremist activities can be seized by the decision of state security services, law enforcement agencies, prosecutor’s office or courts. If deemed extremist, the court can order the materials be destroyed.

The threat for free speech lies in the broad definitions of “extremist activities” and “extremist materials”. Under Belarusian law, extremist activities include “degrading of national honor and dignity”. Such provisions are contrary to international standards of freedom of expression.

“Unfortunately, this is one of the indicators of the current legislation of Belarus – the absolute vagueness of definitions and the absolute possibility of law enforcement to interpret them as they want,” Andrey Bastunets, chairperson of Belarusian Association of Journalists, said.

Critical materials regarded as extremist can end up banned. In 2011, the Ministry of Information issued a warning to Autoradio for broadcasting a message “containing calls for extremist activities”. The warning concerned a phrase by Andrei Sannikau, candidate for the presidency in 2010, that “the fate of the country is solved in the square, not in the kitchen”. The Supreme Economic Court and the National Commission on Broadcasting upheld the warning and the radio was stripped of its frequency.

The law has led to frequent seizures of imported printed material and videos by Belarusian customs offices. Usually, the seized materials are examined to determine if the items are extremist, but it is unclear how to properly get any property out of impound. Often the rightful owners are forced to repeatedly ask for the return of their material.

One of the most sensational cases related to “countering extremism” was the recognition of Belarus Press Photo 2011 album as extremist materials in 2013. The album contained images that won in 2011 the National Press Photo contest — an open annual contest of press photography. In November 2012, 41 copies of the album were seized for expert examination at the border with Lithuania border from three photojournalists, who were organisers of the contest.

Then the Belarusian KGB’s Hrodna regional department initiated proceedings to categorise the album as extremist material. Ashmiany District Court decided that the publication under consideration was extremist. The court’s decision was based on the KGB’s report that “the choice of the photos for the photo album in the aggregate reflects only negative sides of the life of the Belarusian people, together with the author’s own insinuations and conclusions, which, with the view of the socially accepted norms and morals, insults the national honor and dignity of citizens of the Republic of Belarus, diminishes the authority of the state power organs, undermines the trust of foreign states, foreign and international organisations to them.”

As a result, the seized copies of the album were ordered to be destroyed. Further, the court decision served as grounds to withdraw the license from Lohvinau, the publisher of the album. At least 17 anti-extremism motivated seizures of publications have been carried out by Belarusian customs officers since then.

In 2014, the National Commission of Experts on Assessment of Information Productions Regarding Extremist Contents was established as a permanent body with regional subcommissions set up in the regions. Two-thirds of the National Commission’s members are state officials — including representatives of the KGB and customs — who often initiate proceedings to recognise a material as extremist. In the first six months of its existence, the National Commission considered over 100 different publications, 25 of which have been recognised as extremist.

In November 2015, Belarusian customs officers seized two publications for expert examination.

On 10 November 2015, Oleksandr Doniy and four other Ukrainian TV journalists were interrogated and searched by Belarusian officers at the Ukraine-Belarus border while traveling by car to Vilnius, Lithuania. The journalists, who were working for the cultural programme Last Barricade, were held for five hours. A total of 22 items were seized, including five copies of a documentary about the Ukrainian Revolution (1917-1921) and 11 books, among them Confession From a Condemned Cell, Marshal Zhukov and Ukrainians During World War II. The Ukrainian journalists have been accused of importing “extremist literature and audio productions”.

On 19 November 2015, a number of human rights books were seized by customs officers from Aliaksandr Hanevich who was returning to Belarus from Lithuania. Those were De-facto Implementation of International Human Rights Standards: The Experience of Belarusian ILIA Program Alumni, Enlightened by Belarusianness by Ales Bialiatski, My Fight by Valery Hrytsuk, The Death Penalty in Belarus and Pervasive Violations of Labor Rights and Forced Labor in Belarus.

Besides the anti-extremism law, the grounds for stifling freedom of speech are contained in the Law On Mass Media. In the beginning of 2015, the new Article 51.1 was incorporated that set the procedure for restricting access to online information resources. It can be carried out extrajudicially by the decision of the ministry of information upon the request of any state body if the online resource disseminates information prohibited by law. The law also prohibits propaganda of extremist activities. Blocking websites can follow only one violation of the law, within three months since it occurred. This concerns access to both Belarusian and foreign websites viewed in Belarus.

In 2015, the ministry of information has restricted access to 40 websites, 11 of them have been blocked for disseminating extremist materials.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

5 Nov 2015 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

On 11 October, Belarusian president Aleksander Lukashenko won his fifth consecutive election. Whether it was a free and fair election is up for debate.

Belarusian observers, particularly Human Rights Defenders for Free Elections, note the electoral process did not meet a number of core international standards. Claims include that candidates did not receive equal media access, there was a lack of impartiality among election commissions and administrative resources were used in favor of the incumbent. While ballots were cast, political prisoners were held in penitentiaries and there were reports of journalists being harassed.

Even the record share of 36 per cent for early votes need not signal enthusiasm from the electorate. In fact, the early casting of ballots raises concerns of electoral fraud. On 6 October, the deputy dean of the Brest State Technical University, Sviatlana Coogan, stopped two freelance journalists, Aliaxander Liauchuk and Milana Harytonava, from recording interviews with students at a polling station, who said they were forced to participate in early voting by a university representative.

Observers could not visibly ensure the safety of ballots after 7pm and a number of journalists were blocked from working at polling stations during early voting.

Arciom Lyava, a correspondent for the independent newspaper Novy Chas, was forced by clerks to stop photographing a polling station in the Leninski district of Minsk. “As set forth by law, I was taking photos,” he said. This angered Alena Pazenka, headmaster of the school where the station was located. “She stated I was hindering the electoral process. Poll clerks then drew up a statement in relation to me and turned me out from the polling station.”

On election day, at least three other journalists were blocked from documenting events at polling stations. A correspondent for the Polish website Eastbook.eu was blocked from filming the vote count by clerks of a local electoral commission in the Pervomaisky district of Minsk. The chairperson of the commission, Natalia Kunouskaya, threatened to call the police and clerks had fenced off the counting area with chairs so observers couldn’t get close.

As state-run media dominates the landscape in Belarus, the internet is a very important alternative source of information. However, online freedoms were also curbed during the election. During the presidential campaigns, two websites of the privately-owned press agency BelaPAN, were temporarily inaccessible. Sources at the press agency said cyber attacks were launched after they published a critical article about a multi-religious ceremony attended by Lukashenko. The piece featured interviews with students who say they were ordered to attend the event and meet the president. The Belarusian Association of Journalists has expressed concern about the attack, especially in the midst of the electoral campaign.

Blocking access to information about the work of electoral commissions is a common practice for the Belarusian authorities. The independent newspaper Nasha Niva claims that results at some polling stations were re-written after counts were finalised. The data publicised upon completion of vote counting at district electoral commissions did not always coincide with respective results announced at territorial electoral commissions, she says. Niva requested an opportunity to see the results of all polling stations in Minsk from Lidziya Yarmoshyna, chairperson of the Central Electoral Commission. The reply said that the commission did not have the documents, which were at the Minsk City Commission. The city commission did not respond to the request.

The election was followed by an attack on prominent blogger Viktar Nikitsenka who contributed to Radio Liberty Moscow, the radio station Echo Moskvy and korrespondent.net, influential Ukrainian news website. On 13 October 2015, Nikitsenka protested in Minsk’s Independence Square to make his disapproval of the election result known. Friends photographed him outside government buildings holding a sign that read “Lukashenka On Trial”.

Several men in civilian clothes watched from nearby. One of them later approached Nikitsenka and demanded to see his ID and notebook. Half an hour later, when the blogger was leaving the square with his friends, a group of alleged plain-clothes officers seized him in an underpass and dragged him onto a bus. While he was detained, Nikitsenka said was insulted, intimidated and beaten. All his equipment was stolen and data was deleted from his phone and camera. He was taken to the police station, where he was held for approximately two hours before being found guilty of holding an unsanctioned picket, disobeying police officers and insulting a judge at the Maskouski district court. He was fined $492.68 (£319.87).

Nikitsenka later filed a complaint against the officers for unlawful use of force, threats and insults, but it was rejected by the Chyhunachny police department.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

6 Oct 2015 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

In Belarus, dozens of freelance journalists were fined between 2014 and 2015 for working for foreign media without an accreditation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In a country dominated by state-run media, foreign outlets offer an alternative source of information.

Under Belarusian law, freelance journalists who co-operate with foreign media outlets are not considered legal employees of the organisation in question and aren’t entitled to receive the required accreditation. The first freelancer penalised was videographer Ales Dzianisau from Hrodna, a city in western Belarus. He was accused of illegally producing a video which ran on Belsat TV — a Polish state-run channel aimed at providing an alternative to the censorship of Belarusian television — about the opening night of a rendition of Goethe’s play Faust. He was fined €300.

Under Article 22.9(2) of the Belarusian Code on Administrative Offence, the courts can judge journalistic activities without an accreditation as illegal. In each case, the reason for the journalist having committed an offence was not the content of their work, but that they were published through foreign media.

As a rule, the police must consult witnesses — usually a person who was interviewed by the journalist — to prove that a work was made by the journalist accused. This doesn’t always appear to be the case.

An article published by Aliaksandr Burakou on the German website Deutsche Welle resulted in court hearings, talks at the tax office and the seizure of flash drives and computer systems. On 16 September 2014, Burakou’s apartment was searched, as was that of his parents. The journalist was charged with work without accreditation and fined €450. Burakou’s appeal to the country’s Supreme Court was rejected in May 2015.

The Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) strongly condemns the continued prosecution of freelancers. It called the prosecutions a gross violation of the standards of freedom of expression.

In December 2014, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović wrote in a letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belarus, Vladimir Makei, stating: “These undue restrictions stifle free expression and free media. Mandatory accreditation requirements for journalists should be reformed as they hinder journalists from doing their job.” She reiterated her call on to stop imposing restrictive measures on freelance journalists in April 2015.

The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) issued a statement on the situation at its June 2015 annual meeting. It called on the Belarusian authorities to drop the practice of holding freelancers accountable for work without the accreditation. The union also called on the OSCE and the Council of Europe to pay more attention to violations of freelancers’ rights in Belarus.

Nevertheless, since the beginning of 2015, 28 Belarusian journalists have been fined with 23 of those cases taking place in the last six months. Since April 2014, 38 freelance journalists have been fined €200-500, totalling over €8,000.

Dzianisau, the freelance cameraman penalised for making video reports in Hrodna, said: “The most complicated thing for me in this situation is that the authorities shut off the air. At present, I cannot report in the history museum or the museum of religions. I cannot report in the puppet theater, and now in the exhibition hall on Azheshka Street.”

Some freelancers have been brought to trial several times during this period. Kastus Zhukouski has been fined six times and Alina Litvinchuk four times. Some see the pressure on the media in Belarus as increasing due to the upcoming presidential elections on 11 October 2015.

Not so long ago, President Alexander Lukashenko was asked what should be done about journalists receiving fines. In response, he acknowledged that the practice was improper and the matter should be investigated by his press service.

However, many Belarusian freelancers do not believe their situation will change soon. Larysa Shchyrakova, a freelance journalist from Gomel who has been penalised twice this year for co-operating with foreign media, said: “I do not believe there will be any liberalisation because it is contrary to the logic of the authorities. The system in Belarus is ineffective and the prosecution of journalists will always be a priority for the government.”

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|