7 Nov 2013 | Africa, News and features

1) Angola

Manuel Chivonde Nito Alves was held in solitary confinement for printing t-shirts. Image from his Facebook page.

Angolan 17-year-old Manuel Chivonde Nito Alves went on hunger strike on Tuesday, following his arrest on 12 September for printing t-shirts with the slogan “Out Disgusting Dictator”. The message was aimed at the country’s President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who has held power in since 1979. The shirts were to be worn at a demonstration in the capital Luanda, highlighting corruption, forced evictions, police violence and lack of social justice under dos Santos’ regime. Nito Alves has been charged with “insulting the president”, and has now spent almost two months in detention – parts of it in solitary confinement. His family were barred from seeing him, and three weeks went by before he was allowed to speak to a lawyer. The hunger strike is in protest at his “unjust and inhumane treatment”.

2) Belarus

Yury Rubstow wearing the t-shirt that landed him in prison. (Image Viasna Human

Rights Centre)

On Monday, Belarusian opposition activist Yury Rubstow was sentenced to three days in jail for wearing a t-shirt with the slogan “Lukashenko, go away” on the front, and “A four-time president? No. This is not a president but an impostor tsar” on the back.” The message was aimed at the country’s dictator Alexander Lukashenko, during an opposition protest march. He was found guilty of disobedience to police officers under Article 23.4 of the Civil Offenses Code.

3) Swaziland

In 2010, Sipho Jele, a member of Swaziland’s People’s United Democratic Movement, was arrested for wearing a t-shirt supporting the party during a May Day parade. He was arrested under the country’s Suppression of Terrorism Act, and died in custody. The police said he had hanged himself, while the party say the police of killed him.

4) Egypt

The Rabaa symbol displayed at a protest in Turkey (Image Bünyamin Salman/Demotix)

In September, three Egyptian men were arrested for wearing t-shirts emblazoned with the Rabaa symbol. A hand holding up four fingers, it is widely used by those opposing Egypt’s interim military-backed government, and the coup that ushered in in. Mohamed Youssef, the country’s kung fu champion, was also suspended by the national federation for wearing a similar t-shirt during a medal ceremony.

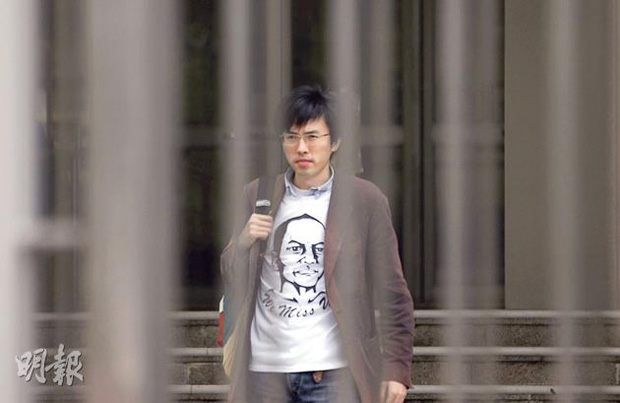

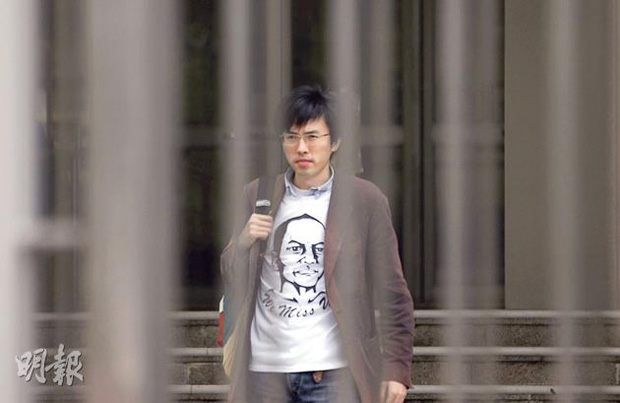

5) Hong Kong

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

An activist from Hong Kong was arrested last December for throwing a t-shirt at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit almost six month earlier, on 1 July. League of Social Democrats Vice Chairman Avery Ng threw a t-shirt with a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang, a Tiananmen Square activist who died under suspicious circumstances only weeks before the visit. Ng was charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place”.

6) Malaysia

Malaysian protester wearing a Bersih shirt. (Image Syahrin Abdul Aziz/Demotix)

In June 2011, Malaysian police arrested 14 opposition activists for wearing t-shirts promoting a rally in Kuala Lumpur calling for election reform. The shirts carried the slogan “bersih” which means “clean”, and is the name of one of the groups behind the protest. Authorities claimed the demonstration was an “attempt to create chaos on the streets and undermine the government”, and they were therefore within their rights to arrest the protesters. They also confiscated t-shirts from the group’s headquarters.

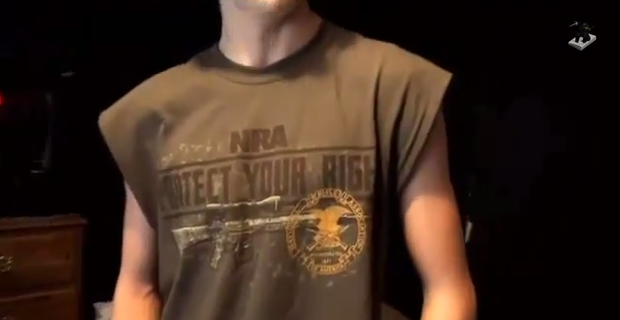

7 & 8) The US

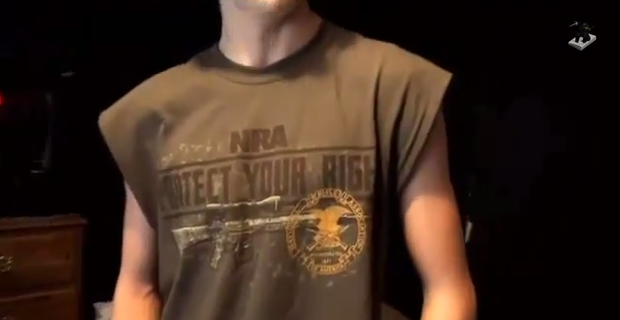

Jared Marcum wearing his NRA t-shirt in a TV report. (Image Youtube)

A 14-year-old student from West Virginia was in April suspended from school and subsequently arrested for refusing to remove a t-shirt supporting the pro-gun National Rifle Association. Jared Marcum was charged with “obstructing an officer” and faced a $500 fine and up to one year in prison.

On the flip side, a Tennessee man was arrested for wearing a t-shirt in support of stricter gun control laws. Stanley Bryce Myszka was wearing a shirt that read “Has your gun killed a kindergartener today?” at a shopping centre, following the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. He was approached by security guards, who called the police when he when he refused to remove the shirt. He was also banned from the shopping centre for life.

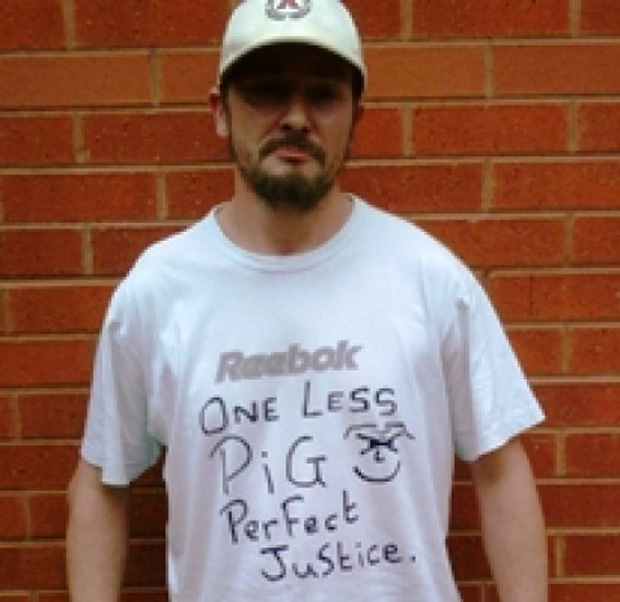

9) United Kingdom

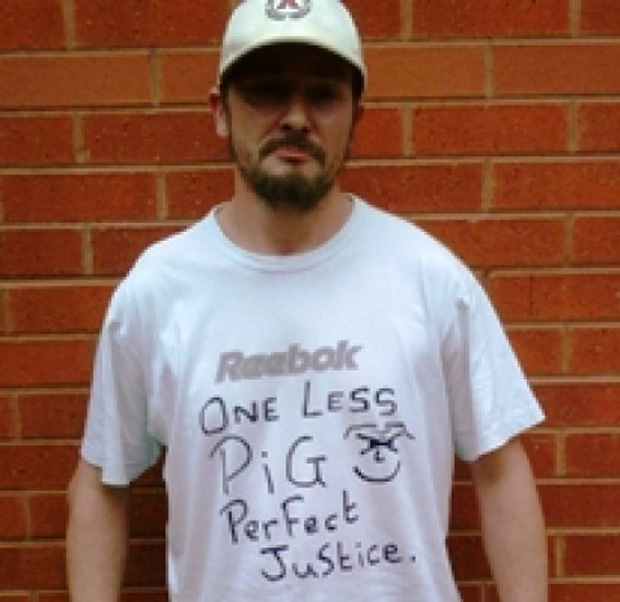

The front of Barry Thew’s t-shirt. (Image Greater Manchester Police)

A Manchester man was in October 2012 sentenced to eight months in prison in part for wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with offensive comments referencing the murders of two policewomen. Barry Thew had written “One less pig; perfect justice” on the front of his t-shirt and “killacopforfun.com haha” on the back. While four months of the sentence was handed down for breach of a previous suspended sentence, he was charged on a Section 4A Public Order Offence for the t-shirt incident.

5 Nov 2013 | Belarus, News and features

The status quo between the European Union and Belarus remains in place. The EU Council prolonged its present sanctions against Belarusian officials last week.

On 29 October 2013 the Foreign Affairs Council of the European Union extended its restrictive measures against Belarus for one more year.

“This is because not all political prisoners have been released, no released prisoner has been rehabilitated, and the respect for human rights, the rule of law and democratic principles has not improved in Belarus,” the press service of the EU Council reported.

The EU reiterated its policy of “critical engagement” with the Belarusian government. At the same time, it updated the list of persons and companies, subjected to the EU sanctions. Thirteen people and five enterprises — all belonging to a Belarusian businessman Vladimir Peftiev — were excluded from the list.

Two more officials were added to the ban list in return: Aliaksandr Kakunin and Yury Trutko, who are the chief officers of Babruysk Correctional Institution No. 2, a prison where Ales Bialiatski, a famous Belarusian human rights defender, is serving a 4.5 year term.

At the moment the EU ban list contains the names of 232 Belarusian officials, including President Alexander Lukashenko, who were involved in human rights violations. They are banned from travelling in the EU; all their possible assets in the European Union must be frozen. The EU ban list also includes 25 companies owned by Yury Chizh and Anatoly Ternavsky, who are sometimes called “the bagmen of the regime.”

The decision of the EU to exclude from the “black list” 13 people, who no longer occupy their positions within the authorities of the country, was criticised by some representatives of Belarusian civil society.

“The reason they were included in the list was their participation to certain extent in human rights violations. For instance, there are several judges who passed politically motivated sentences to civil activists, involved in peaceful protests against the election fraud on 19 December 2010. Despite the fact they left their jobs, none of them has publically announced he or she regrets what they did and they are sorry. The reason why those 13 people were on the list is still there,” Uladzimir Labkovich, an activist of the Human Rights Centre Viasna, told Naviny.by.

Andrei Yahorau, the director of the Centre for European Transformation, thinks there is nothing new in principle in the EU Council decision.

“The reasons for the restrictive measures are still there, so it is natural the EU went on with them. But the changes in the ‘black list’ are purely technical. The issue with the list is not the changes themselves, but the closed way of compiling the list and making these changes. As there are no clearly defined criteria for inclusion to or exclusion from the ban list, such decisions give way to questions and unnecessary speculations,” Andrei Yahorau told Index.

The authorities of Belarus expressed a restrained approval to the EU decision. The Foreign Ministry welcomed shortening of the ban list, but stated the overall approach is still “anti-productive” and insists all sanction must be lifted. There is no change in attitudes towards the issues of human rights of the Belarusian government. For instance, on the day of the EU decision several journalists were detained in Minsk. The official delegation of Belarus confirmed once again at the session of the UN General Assembly in New York this week the authorities of the country do not recognise the mandate of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus, Miklós Haraszti, and are not going to cooperate with him.

The situation seems to be kept dead-locked, and Andrei Yahorau suggests Belarusian civil society “cannot blame the EU for the fact the situation in Belarus is not changing.” Despite the fact the European Union still lacks a clear and effective strategy towards the country, Yahorau believes “if no changes happen inside of Belarus itself, we should not expect anything from Europe.”

This article was originally posted on 5 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

1 Nov 2013 | News and features, United Kingdom

State control of the press is hot topic. On Wednesday, Queen Elizabeth signed off a Royal Charter which gives politicians a hand in newspaper regulation. This come after David Cameron criticised the Guardian’s reporting on mass surveillance, saying “If they don’t demonstrate some social responsibility it will be very difficult for government to stand back and not to act”.

But what does state control of the press really look like? Here are 10 countries where the government keeps a tight grip on newspapers.

Bahrain

Press freedom ranking: 165

The tiny gulf kingdom in 2002 passed a very restrictive press law. While it was scaled back somewhat in 2008, it still stipulates that journalists can be imprisoned up to five years for criticising the king or Islam, calling for a change of government and undermining state security. Journalists can be fined heavily for publishing and circulating unlicensed publications, among other things. Newspapers can also be suspended and have their licenses revoked if its ‘policies contravene the national interest.’

Belarus

Press freedom ranking: 157

In 2009 the country known as Europe’s last dictatorship passed the Law on Mass Media, which placed online media under state regulation. It demanded registration of all online media, as well as re-registration of existing outlets. The state has the power to suspend and close both non-registered and registered media, and media with a foreign capital share of more than a third can’t get a registration at all. Foreign publications require special permits to be distributed, and foreign correspondents need official accreditation.

China

Press freedom ranking: 173

The country has a General Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television and an army official censors dedicated to keeping the media in check. Through vaguely worded regulation, they ensure that the media promotes and toes the party line and stays clear of controversial topics like Tibet. A number of journalists have also been imprisoned under legislation on “revealing state secrets” and “inciting subversion.”

Ecuador

Press freedom ranking: 119

In 2011 President Rafael Correa won a national referendum to, among other things, create a “government controlled media oversight body”. In July this year a law was passed giving the state editorial control and the power to impose sanctions on media, in order to stop the press “smearing people’s names”. It also restricted the number of licences will be given to private media to a third.

Eritrea

Press freedom ranking: 179

All media in the country is state owned, as President Isaias Afwerki has said independent media is incompatible with Eritrean culture. Reporting that challenge the authorities are strictly prohibited. Despite this, the 1996 Press Proclamation Law is still in place. It stipulates that all journalists and newspapers be licensed and subject to pre-publication approval.

Hungary

Press freedom ranking: 56

Hungary’s restrictive press legislation came into force in 2011. The country’s media outlets are forced to register with the National Media and Infocommunications Authority, which has the power to revoke publication licences. The Media Council, appointed by a parliament dominated by the ruling Fidesz party, can also close media outlets and impose heavy fines.

Saudi Arabia

Press freedom ranking: 163

Britain isn’t the only country to tighten control of the press through royal means. In 2011 King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia amended the media law by royal decree. Any reports deemed to contradict Sharia Law, criticise the government, the grand mufti or the Council of Senior Religious Scholars, or threaten state security, public order or national interest, are banned. Publishing this could lead to fines and closures.

Uzbekistan

Press freedom ranking: 164

The Law on Mass Media demands any outlet has to receive a registration certificate before being allowed to publish. The media is banned from “forcible changing of the existing constitutional order”, and journalists can be punished for “interference in internal affairs” and “insulting the dignity of citizens”. Foreign journalists have to be accredited with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Vietnam

Press freedom ranking: 172

The 1999 Law on Media bans journalists from “inciting the people to rebel against the State of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and damage the unification of the people”. A 2006 decree also put in place fines for journalists that deny “revolutionary achievements” and spread “harmful” information. Journalists can also be forced to pay damages to those “harmed by press articles”, regardless of whether the article in question is accurate or not.

Zimbabwe

Press freedom ranking: 133

The country’s Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act gives the government direct regulatory power over the press through the Media and Information Council. All media outlets and journalists have to register with an obtain accreditation from the MIC. The country also has a number of privacy and security laws that double up as press regulation, The Official Secrets Act and the Public Order and Security Act.

This article was originally posted on 1 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org.

31 Oct 2013 | Belarus, News and features, Religion and Culture

Members of the Belarus Free Theatre in fall 2012

Keeping tight control over every sphere of social life is the general policy of the Belarusian authorities. This is true not only about politics, economy or media; arts and culture face censorship as well.

Music: to “black lists” and back

Rock music has always had social protest at its core. Belarusian state ideologists still keep this idea in mind. Lyrics written in the Belarusian language and popularity among opposition supporters are two features that can ensure a rock band gets in trouble.

The authorities of Belarus are not really inventive and sophisticated in the ways to silence the musicians they consider “harmful”. Unofficial “black lists” of rock bands and singers were introduced; they have not been openly public, but managers of radio stations or concert organisers and promoters are aware of them. No tracks of a “forbidden group” are broadcasted by FM-stations; no club organises a gig of a blacklisted artist, even if they know it will definitely be sold out.

During a press conference in January 2013 President Alexander Lukashenko publically asked the Head of his administration to provide him with this “black list” – suggesting there is not one.

“Believe me, I have never made any orders or requests to create any ‘black lists’ to restrict anyone from singing or dancing here. If someone pays such artists for them to heap dirt upon our country, I wish they sing to those who order such music. But I don’t know about any of these facts,” the country’s ruler told a journalist who asked the question.

“His will to get rid of ‘black lists’ might be genuine. We all got to the point when everybody wants to get rid of these black lists: musicians, audience, officials, even the president himself. But it is not easy to do, because the system is in place, and it is the system of fear that works autonomously; it is installed in the society so strongly that even Lukashenko himself barely controls it,” says Aleh Khamenka, a frontman of a famous Belarusian folk-rock band “Palac”.

He admits the situation changed a bit after the press conference in January. For instance, “Palac” was previously black-listed and had to perform under different names (e.g. “Khamenka and friends”) to be allowed on stage in Belarus; now they can openly organise concerts as “Palac” again.

But the “thaw” for rock musicians in Belarus has not been long. A new Presidential Decree, signed in June 2013, suggested an organiser of any concert must receive a special permission in a local Department of Ideology.

“De-facto, in many regions of the country such permissions were to be obtained even before the decree was signed. Now this method of censorship became law,” says Vital Supranovich, a musical producer.

Cinema “spoilt by censorship”

Production of most films in Belarus is funded by the state. But the question is whether anyone sees them.

“Quite a lot of movies are produced, but have you seen any of them? I doubt it. These movies are dull and not interesting for the audience, they are spoilt by existence of censorship. And state ideologists attempt to censor even films they do not fund, by putting pressure on production companies and trying to influence the content,” says Yury Khashchavatski, a Belarusian director, well-known for his documentaries about President Lukashenko and repressions against political opposition in Belarus.

Direct censorship is ensured by “professional propagandists”, who are appointed to manage cultural institutions. For instance, Uladzimir Zamiatalin, who used to be a chief ideologist of the Presidential Administration, was the CEO of Belarusfilm, the state cinema company of Belarus, for quite a long time.

“If you want to make a movie here, film something with a title like ‘Belarus is a country of true democracy’; thus you will be sure you are allowed to produce it without much interference,” says Khashchavatski.

Censorship goes far beyond production. Belarus has a special list of movies that are banned from distribution in the country. It used to be public, and was posted on the official website of the Ministry of Culture, but was deleted from there afterwards – “not to advertise those movies.” At the time it was public, the list included, for instance, Antichrist by Lars von Trier (that won a prize of the Cannes Film Festival) or movies by Tinto Brass.

Theatre: Online performances vs. censorship

Belarus Free Theatre is another example of how artistic freedom is restricted by the authorities of the country. Police officers are people who never miss its performances in Belarus: not because they are ardent theatre goers, but because they stop actors from performing.

“Every time the Free Theatre stages a play in Belarus, there come the police that stop the play. But this is just a visible part of restrictions; real repressions take place outside the stage. All our actors are fired from state theatres, expelled from universities; almost all of them were detained or arrested. We feel this pressure all the time,” says Nikolay Khalezin, the art director of Belarus Free Theatre.

He believes, the theatre is dangerous for the authorities, because it is independent and pays no attention to state censorship and demands from official propagandists. The price the BFT pays for this artistic freedom is harsh: the audience of their plays in Belarus is very limited; they can only stage small performances in tiny semi-clandestine premises they can find. Two of their new plays, Trash Cuisine and King Lear, that gathered huge audiences abroad, are impossible to stage in Belarus – not only because no theatre allows them in, but also because two of the actors were deported from the country in 2008 and are not allowed in.

“We have found new opportunities to present our work to Belarusian public. During Edinburgh Festival we organised live online broadcast of Trash Cuisine; it was on 22 August and it was Sunday, thus many Belarusians were able to watch our play from home,” says Nikolay Khalezin.

The idea worked. The first broadcast received 6,000 views, 85% of which were from Belarus. State censors in Belarus could do nothing about it.

According to Yury Khashchavatski, art helps to inform and educate people; it promotes real human values, rights and freedom – and this is exactly what irritates the authorities. They prefer ignorant citizens that are easier to rule, and they use censorship to prevent people from thinking and questioning the reality presented by official propaganda.

“Why are the authorities so afraid of independent artists? The answer is quite simple: Art is dangerous for the authoritarian regime, because it turns obedient population into real citizens,” says Khashchavatski.

This article was originally published on 31 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org