Contents – The long reach: How authoritarian countries are silencing critics abroad

Contents

The Spring 2024 issue of Index looks at how authoritarian states are bypassing borders in order to clamp down on dissidents who have fled their home state. In this issue we investigate the forms that transnational repression can take, as well as highlighting examples of those who have been harassed, threatened or silenced by the long arm of the state.

The writers in this issue offer a range of perspectives from countries all over the world, with stories from Turkey to Eritrea to India providing a global view of how states operate when it comes to suppressing dissidents abroad. These experiences serve as a warning that borders no longer come with a guarantee of safety for those targeted by oppressive regimes.

Up Front

Border control, by Jemimah Steinfeld: There's no safe place for the world's dissidents. World leaders need to act.

The Index, by Mark Frary: A glimpse at the world of free expression, featuring Indian elections, Predator spyware and a Bahraini hunger strike.

Features

Just passing through, by Eduardo Halfon: A guided tour through Guatemala's crime traps.

Exporting the American playbook, by Amy Fallon: The culture wars are finding new ground in Canada, where the freedom to read is the latest battle.

The couple and the king, by Clemence Manyukwe: Tanele Maseko saw her activist husband killed in front of her eyes, but it has not stopped her fight for democracy.

Obrador's parting gift, by Chris Havler-Barrett: Journalists are free to report in Mexico, as long as it's what the president wants to hear.

Silencing the faithful, by Simone Dias Marques: Brazil's religious minorities are under attack.

The anti-abortion roadshow, by Rebecca L Root: The USA's most controversial new export could be a campaign against reproductive rights.

The woman taking on the trolls, by Daisy Ruddock: Tackling disinformation has left Marianna Spring a victim of trolling, even by Elon Musk.

Broken news, by Mehran Firdous: The founder of The Kashmir Walla reels from his time in prison and the banning of his news outlet.

Who can we trust?, by Kimberley Brown: Organised crime and corruption have turned once peaceful Ecuador into a reporter's nightmare.

The cost of being green, by Thien Viet: Vietnam's environmental activists are mysteriously all being locked up on tax charges.

Who is the real enemy?, by Raphael Rashid: Where North Korea is concerned, poetry can go too far - according to South Korea.

The law, when it suits him, by JP O'Malley: Donald Trump could be making prison cells great again.

Special Report: The long reach - how authoritarian countries are silencing critics abroad

Nowhere is safe, by Alexander Dukalskis: Introducing the new and improved ways that autocracies silence their overseas critics.

Welcome to the dictator's playground, by Kaya Genç: When it comes to safeguarding immigrant dissidents, Turkey has a bad reputation.

The overseas repressors who are evading the spotlight, by Emily Couch: It's not all Russia, China and Saudi Arabia. Central Asian governments are reaching across borders too.

Everything everywhere all at once, by Daisy Ruddock: It's both quantity and quality when it comes to how states attack dissent abroad.

A fatal game of international hide and seek, by Danson Kahyana: After leaving Eritrea, one writer lives in constants fear of being kidnapped or killed.

Our principles are not for sale, by Jirapreeya Saeboo: The Thai student publisher who told China to keep their cash bribe.

Refused a passport, by Sally Gimson: A lesson from Belarus in how to obstruct your critics.

Be nice, or you're not coming in, by Salil Tripathi: Is the murder of a Sikh activist in Canada the latest in India's cross-border control.

An agency for those denied agency, by Amy Fallon: The Sikh Press Association's members are no strangers to receiving death threats.

Always looking behind, by Zhou Fengsuo and Nathan Law: If you're a Tiananmen protest leader or the face of Hong Kong's democracy movement, China is always watching.

Putting Interpol on notice, by Tommy Greene: For dissidents who find themselves on Red Notice, it's all about location, location, location

Living in Russia's shadow, by Irina Babloyan, Andrei Soldatov and Kirill Martynov: Three Russian journalists in exile outline why paranoia around their safety is justified.

Comment

Solidarity, Assange-style, by Martin Bright: Our editor-at-large on his own experience working with Assange.

Challenging words, by Emma Briant: An academic on what to do around the weaponisation of words.

Good, bad and everything that's in between, by Ruth Anderson: New threats to free speech call for new approaches.

Culture

Ukraine's disappearing ink, by Victoria Amelina and Stephen Komarnyckyj: One of several Ukrainian writers killed in Russia's war, Amelina's words live on.

One-way ticket to freedom?, by Ghanem Al Masarir and Jemimah Steinfeld: A dissident has the last laugh on Saudi, when we publish his skit.

The show must go on, by Katie Dancey-Downs, Yahya Marei and Bahaa Eldin Ibdah: In the midst of war Palestine's Freedom Theatre still deliver cultural resistance, some of which is published here.

Fight for life - and language, by William Yang: Uyghur linguists are doing everything they can to keep their culture alive.

Freedom is very fragile, by Mark Frary and Oleksandra Matviichuk: The winner of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize on looking beyond the Nuremberg Trials lens.

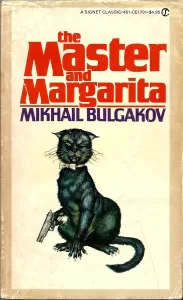

Probably the best-known book of political satire in the Soviet Union was Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, published only after the author’s death in 1966 and promptly banned, which cast Stalin in the role of the devil. As Viv Groskop wrote in her excellent re-reading of classical literature called The Anna Karenina Fix:

Probably the best-known book of political satire in the Soviet Union was Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, published only after the author’s death in 1966 and promptly banned, which cast Stalin in the role of the devil. As Viv Groskop wrote in her excellent re-reading of classical literature called The Anna Karenina Fix: