6 May 2014 | News, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

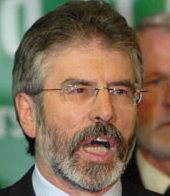

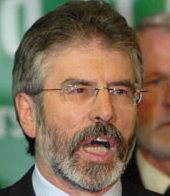

Julia Farrington travelled to Northern Ireland to participate in the 2014 Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival in Belfast. While there she saw four plays that deal with the Troubles as head of Sinn Féin, Gerry Adams, was questioned by police.

A new mural of Adams appeared on the Falls Road in West Belfast what seemed like only a matter of hours after he was taken into custody. Officially launched by Martin McGuiness to a crowd of thousands of Sinn Féin supporters on Saturday, and it was subsequently paint-bombed. The murals, far from being memorials to past struggles, are alive and kicking.

Across town in east Belfast, I went to Bobby “Beano” Niblock’s new play — Tartan at the Skainos Centre — passing the contentious murals of balaclava wearing Ulster Volunteer Force gunmen on the way. Niblock is a rare bird in Northern Ireland as loyalist voices continue to be massively under-represented in the theatre there. The play, though heavily laced with humour and raucously re-enacted 1970s hits, had a very dark message. It tells of betrayal within the loyalist community, as TC, the teenage leader of the Tartan street gang, is mentored, manipulated and ultimately murdered by older members of the community. The level of violence in Tartan completely chilled me; the young men graduating from what were seen as boys toys — crowbars, mallets and axes — to petrol bombs, guns and the crowning awe of a machine gun.

This play of street violence and male rite of passage, was the flip side of Flesh & Blood — three plays written, produced, directed and designed by women I had seen the previous day in a run through a week before they open at the Grand Opera House. I was invited by one of the playwrights, Jo Egan, whose play Sweeties revolves around the true story of a seemingly unperturbed victim of paedophilia and the devastation it causes her complicit friend. The other two plays were by comic genius Brenda Murphy and first time playwright and former leader of the Progressive Unionist Party, Dawn Purvis. All three tell stories centre on the experience of women and girls, firmly rooted in the domestic setting of home, street and neighbourhood; in the case of Sweeties, trapped by agoraphobia in a front room, or Dawn Purvis’ play through the eyes of a young girl, watching and commenting on life on her street, with the Troubles forming the backdrop. Brenda Murphy’s play was a deeply moving portrait of her mother’s struggle to bring up six illegitimate children who she had with a married man who lived around the corner.

Those three plays were so good to see. Women playwrights are strangely under-represented all over this country, when you compare to a much more equal landscape in fiction, biography and other written forms. But hearing those voices, the reality and humour of women in Belfast, a city which I found to be so acutely male dominated, was brilliant. I laughed and cried, and came away deeply affected by the lives I had seen on stage, the courage, compassion and humour of women left to deal with the fallout of male violence.

But in all cases the stage here is seeing untold stories, and in some cases unwelcome stories, coming to the surface; retelling, unearthing, revealing complex, individual stories that are hidden within the expression of communal identity of the murals.

This article was posted on May 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 May 2013 | Politics and Society

Yesterday’s Belfast Telegraph yesterday ran a strong leader on the fact that the Defamation Act, recently passed into law after a long campaign by Index and our partners and supporters in the Libel Reform Campaign, will not extend to Northern Ireland.

The paper comments:

The absence of any proper explanation as to why Northern Ireland has turned its back on the reforms is baffling. We would urge politicians to throw their weight behind a Private Members’ Bill put forward by [Ulster Unionist Party] leader Mike Nesbitt to have the Westminster reforms introduced here. The reforms do not stop people who have a genuine grievance and want to clear their reputation, but they raise the threshold for taking actions. They also create a stronger public interest defence in defamation cases. Surely, it is in the public interest to reform our outdated libel legislation.

Couldn’t agree more.

Meanwhile, Belfast lawyer Paul Tweed has already been hinting that the Titanic town could become the new “town called sue”, tweeting “Looks like libel litigants will now have to cross the Irish Sea to Belfast or Dublin in order to get access to justice.” A 1 May interview with Tweed in the Belfast Telegraph summed Tweed’s position up, beginning with: “Mention libel tourism and the first Northern Ireland lawyer most people think of is Paul Tweed.”

The same article notes that Tweed is currently campaigning for no-win-no-fee libel claims to be allowed in Belfast, noting “”The fact is that unless you have money you cannot bring a defamation action in Belfast. As things stand, I prefer to act in Dublin, not Belfast.”

Tweed’s firm Johnson’s would appeal to have stolen a march on London libel lawyers by already operating in Dublin, Belfast and London. Will other firms follow suit? Will we see Carter-Ruck taking the ferry to Larne? Schillings and Shilelaghs? The ruling parties in Northern Ireland should back Nesbitt’s attempt to bring libel reform to Northern Ireland before Belfast becomes the capital of censorship.

Padraig Reidy is senior writer for Index on Censorship. @mePadraigReidy

22 Jun 2011 | Index Index, minipost, News

Press Association photographer Niall Carson, who was covering violence in east Belfast was shot in the leg during a riot on Monday night. Stones, fireworks, petrol bombs and improvised missiles have been thrown between rival groups of masked rioters. Carson was taken to Royal Victoria hospital where he is now said to be in a stable condition.

4 Apr 2008 | Comment

Gerry Adams and Sinn Féin are trying to stifle debate in Belfast’s media, writes Anthony McIntyre

Gerry Adams and Sinn Féin are trying to stifle debate in Belfast’s media, writes Anthony McIntyre

Gerry Adams of Sinn Féin is the current Westminster MP for West Belfast. For decades he rightly campaigned against censorship policies crafted by successive British and Irish governments for the purposes of undermining his party. British readers may recall him as the only member of the House of Commons they could see but not hear. On each occasion that he appeared on TV over a six-year period from 1988, an actor’s voice was used to dub his words. On radio he was neither seen nor heard, the dubbing procedure again in play. It was only one of a range of draconian measures applied to silence him and his party. Former Irish Journalist of the Year Ed Moloney has repeatedly asserted that such censorship prohibited dialogue and consequently prolonged Northern Ireland’s violent conflict.

Although a victim of harsh political censorship, Adams’ disinclination to use this invidious tool of political repression has been less than salutary. Never a figure at ease with even the mildest form of political criticism, he has persistently sought to undermine those who do not see the world through his eyes and who are prepared to voice their misgivings publicly. Virtually everyone who has left Sinn Féin since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement a decade ago has highlighted the suppression of debate among their reasons for quitting. Adams has no record of speaking out against those murdered, kidnapped or beaten by his party’s military wing simply because they chose to dissent from his political project. On occasion Adams has hit out at those daring enough to have a public ‘poke’ at his leadership. Elsewhere he has been on record saying that people should not be allowed to even think that there is any alternative to the Good Friday Agreement. There is no concession to the idea that without audacious thinking, West Belfast intellectual life would be even more restricted than it currently is.

(more…)