19 Feb 2015 | News, United Kingdom

How does one avoid being a potential target for murder by a jihadist? If you’re Jewish, you probably can’t, unless you attempt to somehow stop being Jewish (though I suspect, much like the proto-nazi mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, IS reserves the right to decide who is a Jew).

Everyone else? Well, we can be a little quieter. We can, perhaps, not hold meetings with people who have drawn pictures of Mohammed. We can, perhaps, recognise that the right to free speech comes with responsibilities, as The Guardian’s Hugh Muir wrote. The responsibility to be respectful; the responsibility not to provoke; the responsibility not to get our fool selves shot in our thick heads.

This seemed to be the message coming after last weekend’s atrocity in Copenhagen. Oddly, I just found myself hesitating while typing the word “atrocity” there. Felt a little dramatic. Because already, amid the condemnations and what ifs? and what abouts? that have dogged us since this wretched year kicked into gear with the murders in Paris, already, the pattern seems set. Young Muslim men in Europe get guns, and then try, and for the most part succeed, in killing Jews and cartoonists, or people who happen to be in the same room as cartoonists. Then the condemnation comes, then the self-examination: what is it that’s wrong with Europe that makes people do these things? The things we definitely know are wrong are inequality and racism, so that’s where we focus our attentions. Europe’s past rapaciousness in the Middle East, or its recent and current interventions: these, on a societal level, are believed to be mistakes, so they too, must be examined (it could be argued that non-intervention, particularly in Syria, has been at least as much of a factor).

What else? Maybe we caused offence. Maybe we crossed a line when we allowed those cartoonists to draw those pictures. Maybe that’s it. We’ve offended two billion or so Muslims, and of course, some of them are bound to react more strongly than others. So we’d best be nice to them in future (we leave the implied “or else” hanging). And being nice means not upsetting people.

This is, as I’m fairly certain I’ve written before, a patronising and divisive way of looking at the world. Patronising because of the casual assumption that Muslims are inevitably drawn to violence by their commitment to their faith, and divisive both because it sets a double standard and because it entrenches the notion that Muslims are somehow outside of “us” in European society.

That divisiveness is not merely useful to xenophobes and Islamophobes. It is equally important in the agenda for many types of Islamist.

Take a small but instructive example. The BBC Two comedy Citizen Khan is possibly the most normal portrayal of Muslims British mainstream comedy has ever seen. The lead character started life as an absurd “community leader” in the brilliant BBC 2 spoof documentary Bellamy’s People, before morphing into an archetypal bumbling silly sitcom patriarch in his own successful show.

Citizen Khan is a classic British sitcom in which the family happen to be practicing Muslims. It is not cutting-edge comedy, boldly taking on racial and religious blah blah blah; it’s family entertainment.

Cause for celebration, surely, that practicing Muslims are being portrayed as normal people rather than radical weirdos? Not according to the risibly-titled Islamic Human Rights Commission, a small group of Ayatollah Khomeini fans who have nominated Citizen Khan for its annual Islamophobia award, claiming the show features “Muslims depicted as racist, sexist and backward. Obviously”. They don’t want to see Muslims on television as normal people, because that would undermine the division they seek to engender. I doubt any of the people at the IHRC who suggested Citizen Khan was Islamophobic are genuinely hurt or offended by the programme; if they are, it’s because it features a portrayal of Muslim people, by Muslim people, that they cannot control. It’s really got nothing to do with “offence”.

Likewise, I refuse to believe that the killers of Paris or Copenhagen have been sitting around stewing for years over “blasphemous” cartoons. To imagine that these murders took place because of perceived slight or offence is to cast them as crimes of passion. I don’t buy it. These were, at best in the eyes of the killers, legal executions for the crime of blasphemy, carried out because their interpretation of the law demanded that they do so.

The same interpretation of the law means that these men are allowed, mandated even, to kill Jews. So that is what they do.

However much cant we spill about “no rights without responsibilities” (that is, the preposterous “responsibility” not to offend), the fact that people are being murdered for who they are rather than what they did should make us realise that there is no responsibility we can exercise that will mitigate the core problem: a murderous totalitarian ideology has taken hold. It has territory, it has machinery, it has propaganda, and it has a certain dark appeal, just as totalitarian ideologies before have had. ISIS or Daesh or whatever you choose to call it is calling people to its cause. AQAP competes for adherents.

Some will point to the previous violent criminal records of the killers in Paris and Copenhagen and say “You see? They were mere thugs: the ideology barely comes into it.” But come on, who do you think the Brownshirts recruited? Bookish dentists? The fact that thugs are drawn to a thuggish ideology mitigates neither.

This week, Denmark’s only Jewish radio station went off air due to security concerns. This is where responsibilities before rights leads us. Shut up, keep quiet, and if something happens then it’s your fault for being irresponsible. Irresponsible enough to wish to practice your culture and religion freely. Irresponsible enough to “offend” murderers with your very existence. This line of thinking is not just cowardly, it is accusatory.

The correct answer to the request that we show responsibility with our rights, is, as revolutionary socialist James Connolly put it, “a high-minded assertion” of rights themselves. Not just the right to speak freely, but the right to live freely.

This article was posted on 19 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

28 Jan 2015 | mobile, News, United Kingdom

Galileo is “vehemently suspect by this Holy office of heresy, that is, of having believed and held the doctrine (which is false and contrary to the Holy and Divine Scriptures) that the sun is the centre of the world, and that it does not move from east to west, and that the earth does move, and is not the centre of the world…”

Sentencing at the Inquisition of Galileo,

22 June 1633

Every philosopher, prophet, scientist and great political and social reformer of their day has started as a heretic. Mohammad blasphemed against the polytheist social order of Mecca, Jesus against the monotheistic legalese of the Temple, and Moses before them against the idols of the Children of Israel. The right to heresy, to blasphemy, and to speak against prevalent dogma is as sacred and divine as any act of prayer. If our hard earned liberty, our desire to be irreverent of the old and to question the new, can be reduced to one, basic and indispensable right: it must be the right to free speech. Our freedom to speak represents our freedom to think, our freedom to think our ability to create, innovate and progress. You cannot kill an idea, but you can certainly kill a person for expressing it. For if liberty means anything at all, it is the right to express oneself without being killed for it.

The importance of internalised liberalism in contemporary British society has come to represent a cornerstone of modern Liberal Democrat thinking.1 This paper aims to extend that notion by arguing that liberalism is an idea that should be actively, universally and externally asserted, among, between and across communities, cultures and borders. A certain neoorientalism has crept upon us, partly in reaction to the failed militarism of the neo-conservative years, but mainly attributable to historical self-critical attitudes towards the British Empire. This neo-orientalism interprets liberalism as a Western construct ill-fitting to non-Western cultures. Struggling, dissenting liberals within minority community contexts find that they have no greater enemy than these neo-orientalists who lend credence to the idea that they are somehow an inauthentic expression of their ‘native’ culture. This view, while embracing moral relativity, reduces other cultures to lazy, romanticised and static cliches. Far worse, it ends up not just tolerating but actively promoting illiberal practices in the name of assumed cultural authenticity, even where such promoted practices are in fact ahistoric, inauthentic neo-fundamentalisms.

There is a great betrayal of minorities-withinminorities afoot. The price of this betrayal in modern Britain is monocultural ghettos that stifle minority opportunities by acquiescing to the silencing of innovative voices, in the name of this assumed cultural authenticity. Only by the universal reassertion of free speech will those silent voices stand any chance of being heard. Free speech is not a ‘Western’ ideal but a human one.

Globalisation and identity

Rapid globalisation has helped to erode national identity. Encouraged by innovations in international travel and communications, we have witnessed instead the rise of lateral transnational identities that reach across borders, rather than within them, to find affinity. Consequently, previously isolated pockets of parochialisms are connecting, providing a sense of belonging to global causes beyond geographical boundaries.

A common fear is that living in multi-ethnic and multi-religious societies leads to the disintegration of one’s own culture. Some, especially those from minority communities, feel the need to protect themselves against this threat by ardently clinging on to, and exaggerating, a narrow form of their ethnic or religious identity. ‘Cultural differences’ are therefore emphasised and ring-fenced more than they otherwise would be.

Of course it is possible to do this in a healthy way, and many do. But some modern cultural insecurities have warped to form a broad anti-establishment sentiment in Britain. Victimhood is used as means to create a sense of besiegement, leading to highly exclusionary identity formations. The rise of identity politics and reactionary political or religious ideological trends across Europe can be said to be inspired

by this fear of losing one’s identity, and sense of belonging, via globalisation.

It is usually the case that those who are most passionately against the status quo are the most active at proselytising, and so it has come to pass that it is the political extremes – Far Right, Anarchist and Islamist – who have best exploited this ability to build exclusionary, transnational identities. Here, globalisation can be said to have ‘sharpened the differences and increased cultural confrontations’2 in Europe rather than creating integrated, multicultural melting pots.

Cultural relativity

In response to tension created by the rise in reactionary political trends, liberal society has understandably been inclined to reduce the risk of conflict. Words, images and actions that could be deemed offensive by certain sections of a community, especially a religious community, are subsequently avoided by us in apprehension, worried such actions may create an unwanted reaction. In essence, unhealthy taboos that ideally need to be broken are simply further entrenched. In some cases these taboos are actively and tragically enforced in the guise of defending diversity.

In what would now be considered a preposterous – and thankfully illegal – measure, in 1993 the London Borough of Brent proposed a motion to make Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) legal. The motion called for FGM to be classed as a “right specifically for African families who want to carry on their tradition whilst living in this country”. Ann John, a local Brent councillor at the time, successfully opposed this motion and tabled her own amendment in which she called FGM “barbaric” and said it was “no more a valid cultural tradition than is cannibalism”. But this was the 1990s, the decade of unhinged state-sponsored monocultural ghettoisation, unfortunately named multiculturalism. Subsequently, for her heresy Ann suffered a tirade of abuse and threats. She was called a “colonialist missionary” who “thinks she knows what is best for Africans” and even threatened with mutilation herself. It took until 2014 for Brent Council to finally teach FGM prevention in all its schools. Yet according to statistics cited by the government’s Department for International Development (DfID), over 20,000 girls under the age of 15 are still at risk of FGM in the UK every year.3

At the time of writing, Britain is yet to witness one successful conviction for this reprehensible practice. Ann John has an explanation for this, interviewed in 2014 she “believes her treatment scared off other people from speaking out against FGM for years out of a fear of being called racist”.4

As with homophobia, the cultural war against FGM is slowly being won in Britain. But the fact that many still feel unable to make negative judgements about other practices found in alternative cultures, and our own, is deeply problematic. We liberals will be rightly judged by the extent of our concern for the weakest among us. In today’s Britain, the weakest among us are often assumed to be minority communities. In fact, the weakest are those minorities-within-minorities for whom the legal right to exit from their communities’ constraints amounts to nothing before the enforcement of cultural and religious shaming. Those most vulnerable would include dissenting religious sects, feminists, LGBT and apostates, all of whom may question the prevailing dogma within their group identity. Liberalism in this instance is duty bound to unhesitatingly support the dissenting individual over the group, the heretic over the orthodox, innovation over stagnation and free speech over offence. Or, as John Maynard Keynes would say, to “appear unorthodox, troublesome, dangerous, disobedient to them that begat us”.5

Instead, what is often the case is that prevailing neo-orientalist thinking would either remain silent, or criticise those who do seek to challenge dogma, for ‘causing offence’. An assumption is made here about what ‘authenticity’ in a given culture is. Subsequent actions and advice, policy or otherwise, are patronisingly given on the basis of this assumption.

Confirmation bias leads to seeking reaffirmation for this assumption from the very ‘community leaders’ who stand most to gain by reaffirming it. Few stop to ask why it is assumed that Britain’s three million Muslims, the vast majority of whom are not religious, would wish to engage the public through Citizen Khan6 like conservative figures.7

Not only is this assumption lazy, but it suggests that each culture is effectively a homogenous, static group; the members of which think the same way and would all be equally offended by the same thing, none of whom can speak as individuals, but like native savages would require ‘chiefs’ to speak on their collective behalf. If seeking unity in politics is fascism, then seeking unity in religion is theocracy. Liberalism cherishes internal diversity in both.

When such cultural relativity becomes the norm, more progressive and liberal elements within minority religious communities or cultural groups in particular are betrayed, only then to be besieged by all sides. Through this reductionist quest for cultural ‘authenticity’, anything deemed Western is incrementally excluded by our neo-orientalists as inauthentic, until only the most conservative, dogmatic and regressive voices remain – which are, ironically, entirely a product of modernity in themselves.

Alas, this search for authenticity is a battle that only fundamentalists and fascists can win. Bigotry is not merely generalising a culture, religion or race for hate. Those who generalise a culture, religion or race in order to display a patronising love, more befitting to a pet, must also be considered bigots. And only the most regressive forces stand to gain by exaggerating their culture, religion or race, either in defiance or compliance to bigots. Liberalism must seek out the individual, not the stereotype. Because such reductionist approaches are nothing but an outdated superiority complex that should have died along with the Empire.8 Because to deem the ‘poor natives’ as being too primitive to grasp liberalism, and to subsequently hold them to and judge them by a lower standard, is a poverty of expectation.

Let us take the example of the Law Society of England and Wales. In early 2014, the Law Society, a necessarily secular institution, published a practice note advising solicitors on how to draft wills in accordance with “Sharia Law”; except there is no single version of Sharia, and in Arabic, Sharia is a noun, not an adjective to describe the noun ‘law’. These guidelines included assertions that “Sharia Law” endorses the disinheritance of apostates and adopted children, and discriminates against women. It is true that English Common Law allows for inheritance to be decided in any way that pleases the testator. The concern here however is why the Law Society felt entitled not only to intervene in an intra-religious debate about the nature and applicability of Islam today, but that when doing so it picked the most regressive form of medievalism and promoted it as ‘authentic’ Islam,9 thus betraying, and further isolating, liberal reforming Muslims from the outset.10

The publication of cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten are a case in point. It was only when the press started approaching certain ‘community leaders’ that an angry response became apparent, especially since only religious imams were approached.11

Likewise, I recently tweeted an innocuous stick figure, not drawn by me, of an image called ‘Mo’ saying “Hi” to an image called ‘Jesus’. The image called ‘Jesus’ said in reply, “How ya doin?”. I did so because, as a Muslim, I felt it was necessary to make the point that I was not offended by a benign cartoon in light of media portrayals of all Muslims as overly-sensitive. I did so in the aftermath of a live TV debate on the subject. Ironically, and while I vehemently disagree with the veil, my intervention came in the context of attempting to defend the rights of a veiled Muslim woman who had just been told that her veil ‘offends’ people. After asserting her own right to wear what she likes, this lady retorted to a man next to her that he however could not wear his tee-shirt with the above described stick figure labelled ‘Mo’, because it offends her. My reply was that people are free to take offence at how I dress, but they are not free to insist that I dress in a way that does not offend them. This principle applies to all, fairly. I then retweeted that I was not offended by this stick figure labelled ‘Mo’. Blasphemy is in the eye of the beholder. I was subsequently inundated with a torrent of abuse and violent threats by some vocal but reactionary Muslims. More telling was the chastisement by many non-Muslim neo-orientalists who accused me of being insensitive to ‘Muslim feelings’, as if I myself was not one of these Muslims with some ‘feelings’ I needed to express.

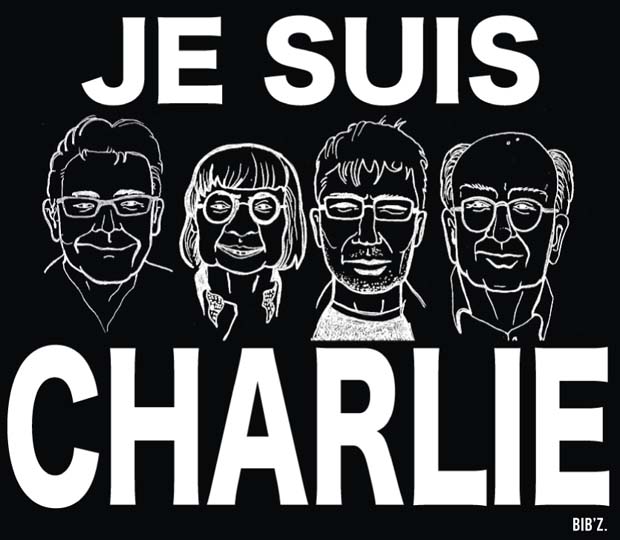

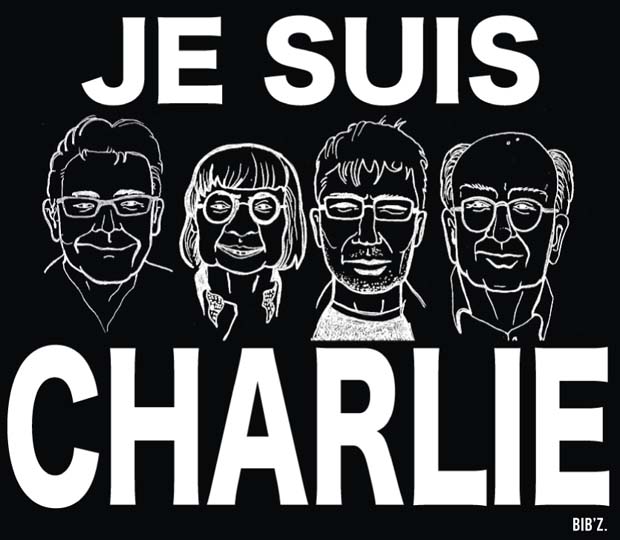

And then came the attacks on Charlie Hebdo in Paris.

Taking the easy route by condemning the radical for causing unnecessary trouble is overwhelmingly tempting, and incredibly lazy. Liberals would instinctively see the birth pangs of progress through such heresy. Cultural relativism has created an absurd situation whereby minorities-within-minorities are no longer free to move intra-cultural debates forward. I recall once as a child that a passerby approached a gay couple on the street and told them not to hold hands in public, asking the gay couple “are you deliberately trying to offend us?” I rest my case.

The inconvenient minority

And so that great lynchpin of liberty, freedom of speech, as defined by Article 19 of the UDHR,12 is being eroded by exclusionary group identities. These groups struggle to compete over who is more offended, and who is more entitled. Civil society is now expected to self-censor and the term ‘tolerance’, as explained by Flemming Rose, is ‘no longer about the ability to tolerate things for which we do not care, but more about the ability to keep quiet and refrain from saying things that others may not care to hear’.13

This brings me to the term ‘Islamophobia’, often deployed – even against other Muslims – as a shield against any criticism, and as a muzzle on free speech. If heresy is to be celebrated, it follows that no idea, no matter how ‘deeply held’, is given special status. For there will always be an equally ‘deeply held’ belief in opposition to it. Hatred motivated specifically to target Muslims, people like me, must be condemned.

But to confuse this hatred with satirising, questioning, researching, reforming, contextualising or historicising Islam, or any other faith or dogma, is as good as returning to Galileo’s Inquisition. It follows, therefore, that any liberal naturally concerned with a fair society must be the first to openly defend against the erosion of free speech, especially when deceptively done in the name of minority rights.

Amidst a wave of self-doubt, blasphemy laws, though formally abolished in the UK, are effectively being revived by a cultural climate that purports to be liberal yet upholds illiberalism. Ultimately, restrictions on freedom of speech achieve only one thing – the domination of regressive ideals. Reactionaries are the first to take offence, and the first to demand punitive action against those who they deem offensive. In this way we actively empower illiberal dogma in the name of ‘diversity’, while abandoning vulnerable activists within minorities in the name of ‘respect for difference’.

Neo-orientalist reticence is in part driven by genuine concern of a racist backlash against minority communities by right wing bigots. Britain has become a place where white racists and Christian fundamentalists ally to the Right on domestic issues, while Islamists and Muslim fundamentalists ally to the Left on foreign policy issues. Both groups are able to co-opt the political rhetoric of each political wing to fuel their narrative of victimhood. Both are able to intimidate the ‘other’. Though this fear of racism is genuine – I have personally had to endure being violently targeted by racists over a prolonged period – ignoring Islamist extremism in the name of respect for difference will only fuel racism more by

feeding the Far Right’s victimhood narrative. Both extremes are in perfect symbiosis, feeding off each other to justify their respective grievances. But the difference between fairness and tribalism is the difference between choosing principles and choosing sides. Only a liberal torch can consistently shine through the fog of Far Right and Islamist extremisms and assert itself with any level of consistency.

George Orwell said, “The point is that the relative freedom which we enjoy depends on public opinion. The law is no protection. Governments make laws, but whether they are carried out, and how the police behave, depends on the general temper in the country. If large numbers of people are interested in freedom of speech, there will be freedom of speech, even if the law forbids it; if public opinion is sluggish, inconvenient minorities will be persecuted, even if laws exist to protect them…” To Orwell’s admirable concern for inconvenient minorities, I would only add one idea: the cost of betraying people’s right to heresy is that inconvenient minorities-withinminorities are, in fact, the very first to be persecuted.

Maajid Nawaz is author of his autobiographical story Radical, Chairman of the counter-extremism organisation Quilliam, and a Liberal Democrat Parliamentary candidate for London’s Hampstead and Kilburn. The author would like to thank Hannah Larn and Ghaffar Hussain for their help. Maajid Nawaz can be contacted on Twitter @MaajidNawaz. The opinions expressed in this guest post are the author’s own.

This article was originally published in Centre Forum. It is reposted here with the author’s permission.

Footnotes:

1. David Laws and Paul Marshall (eds), ‘The Orange Book: Reclaiming Liberalism’, London, 2004

2. Erika Harris, Nationalism: Theories and Cases, Edinburgh, 2009

3. Improving the Lives of Girls and Women in the World’s Poorest Countries, DfID

4. Evening Standard, ‘Ann John: I was branded a colonialist for fighting against ‘barbaric’ FGM’, Anna Davis, 28 March 2014.

5. John Maynard Keyes, ‘Am I a Liberal?’, Liberal Summer School, August 1 1925

6. Citizen Khan, BBC One sitcom, written and played by Adil Ray

7. See Amartya Sen: ‘Identity and Violence’ Allen Lane, London 2006

8. For further reading see Edward W. Said, ‘Orientalism’, 1978

9. See the Law Society, Sharia succession rules, 13th March 2014 and a response by the Lawyers Secular Society (LSS) ‘The Law Society should stay out of the theology business’

10. Only after some laudable campaigning, not least from the Lawyer’s Secular Society and One Law for All, among others, did the Law Society eventually – and quietly – drop this practice note.

11. See Kenan Malik’s Enemies of free speech, Index on Censorship, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2012.

12. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers’.

13. Flemming Rose, cultural editor of the Danish newspaper JyllandsPosten, in Kenan Malik’s essay Enemies of free speech, Index on Censorship, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2012.

13 Jan 2015 | News, United Kingdom

Nadhim Zahawi is a member of the BIS Select Committee, the Party’s Policy Board and MP for Stratford on Avon. This article is from Conservative Home

You can’t kill an idea by killing people. The sickening attack on Charlie Hebdo has shown that to be true. As France mourns her dead, millions around the world are discovering the work of her bravest satirists. Nous sommes Charlie.

Unfortunately, the same is true of the terrorists. Bin Laden may be at the bottom of the sea, but his poisonous ideology lives on. As long as it inspires deluded young men to kill, these attacks will keep happening. We can’t win this fight unless we also win the battle of ideas.

This is an urgent task. Thousands of EU citizens have travelled to the Middle East to serve under ISIS’s black banner. Many will return with combat experience and carrying the virus of radicalism. Some will be eager to put their new terrorist skills to work. It’s vital that we stop them.

Our security services have an important role to play, but research suggests that the most effective way of tackling terrorism is “changing the narrative”. That means challenging the stories used by extremists to justify their twisted worldview.

First and foremost, this means rejecting the idea that this this is a clash of civilizations: Islam versus the West. The reality is that jihadists have claimed more lives in the Islamic world than anywhere else. In December last year, the Pakistani Taliban gunned down 132 schoolchildren in their classrooms. On the same day as the attack in Paris, a car bomb exploded in Yemen killing at least 38 people. Muslim-majority countries, as much as the West, have a clear interest in stamping out this ideology.

It’s time the Islamic world took a leadership position on this issue. When the news from Paris broke, countries such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Afghanistan were quick to condemn the attacks. Yet all three have legal systems carrying the death penalty for blasphemy. In virtually every Muslim-majority country, publishing a magazine like Charlie Hebdo would earn you a fine or imprisonment.

These laws support the idea that religious offence is a crime to be punished rather than a price we must pay for freedom of expression. They also fuel extremist violence. In Pakistan, blasphemy charges are often levied at religious minorities on the flimsiest of pretexts. Those accused are sometimes lynched by vigilante mobs while awaiting trial. Politicians who’ve dared to speak out against the laws have been assassinated.

One of the best tributes we could pay to the brave men and women of Charlie Hebdo would be to use our diplomatic influence to get some of these laws repealed. Change won’t happen overnight, and we will have to be patient with these countries. After all, the last successful prosecution for blasphemy in Britain was as recent as 1977, and the laws only came off the statute books in 2008.

I am not arguing that we should preach to Islamic governments; but nor should we turn a blind eye to this issue. Reforming attitudes to blasphemy would send a powerful message to extremists: freedom of speech isn’t just a Western value – it’s our common birthright as human beings.

And we shouldn’t be frightened of having a conversation about religion here at home. Talking about religion doesn’t come naturally. As a culture, we ‘don’t do God’. Yet it’s vital that mainstream Muslims feel comfortable discussing their faith in public. They, not the Government, are best placed to take on the dodgy imams and self-appointed sheikhs in open debate.

The Qur’an is clear that it’s the role of Allah, not man to judge unbelievers. In the 7th Century, Ali bin Abi Talib, the cousin of the Prophet and a leader of the original Islamic Caliphate, said: “Whoever does not accept others’ opinions will perish”. There’s a sound Islamic case for freedom of expression, and it needs a good airing.

Last, we have to practice what we preach. If we want Muslims to come out and say “not in my name” every time there’s a terrorist atrocity we too need to be vocal in our condemnation of attacks on Muslims and mosques in the West.

Charlie Hebdo was a target because humour is dangerous. You can’t be the all-powerful Islamic Caliphate and be the butt of someone else’s joke. The goal of terrorism is to frighten us – so laughter is one of our most powerful weapons.

This article was originally posted at Conservative Home on January 12, 2015. It is reposted here with permission.

31 Jul 2014 | Ireland, News, Pakistan, Religion and Culture

It was, apparently, the posting of a “blasphemous image” on Facebook that led an angry mob to burn down houses with children inside them.

It’s been suggested that it was a picture of the Kaaba, Islam’s holiest site, that provoked the mob in Gujranwala in Pakistan. They rallied last Sunday at Arafat colony, home of 17 families belonging to the Ahmadi sect. As police stood by, houses were looted and torched. At the end of the night, a woman in her 50s, Bushra Bibi, and her granddaughters Hira and Kainat, an eight-month-old baby, were dead. None of them had anything to do with the blasphemous Facebook post.

Was the image even blasphemous? In some ways, it doesn’t really matter. What matters was that it was posted by an Ahmadi, whose very existence is condemned by the Pakistani penal code.

Ahmadiyya emerged in India in the late 19th century. It is a small sect based on the belief that its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, was, in fact, the Mahdi of Muslim tradition. This teaching is rejected by Orthodox Sunni Islam.

In Pakistan, this means that being a member of the Ahmadiyya sect is dangerous. The law says you cannot describe yourself as Muslim. You cannot exchange Muslim greetings. You cannot describe your call to prayer as a Muslim call to prayer. You cannot describe your place of worship as a Masjid.

Any Ahmadi who “any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims” can be imprisoned for up to three years.

Ahmadis suffer disproportionately from Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, but they are not the only ones who suffer. Accusations of blasphemy are frequently levelled at members of other minorities and at mainstream Muslims too. Often, this is done out of sheer spite. Often it is done to settle scores.

As the New Statesman’s Samira Shackle has pointed out, amid the chaos and fear generated by the law, it’s often difficult to find out what people are actually supposed to have done, as media hesitate to repeat the alleged blasphemy lest they themselves be accused of the crime.

The fevered atmosphere created by the laws mean that to oppose them can be fatal. In Janury 2011, Punjab governor Salmaan Taseer was killed by his own bodyguard after he pledged to support a Christian woman, Aasia Bibi, who had been accused of the crime. Taseer’s assassin claimed that the governor had been an “apostate”. He was widely praised by the religious establishment. Three months later, Minority Affairs Minister Shahbaz Bhatti was killed, apparently because of his belief that the blasphemy law should be changed.

Meanwhile, an amendment proposed by Taseer’s colleague Sherry Rehman, which would have abolished the death penalty for blasphemy, was dropped. Rehman was posted to diplomatic service in the United States later that year, amid allegations that she herself had committed some kind of blasphemy.

The number of blasphemy cases is steadily rising, and Human Rights Watch recently claimed that 18 people are on death row after being found guilty of defaming the prophet Muhammad, though no one has as yet been executed.

The laws may seem archaic, but they are in fact utterly modern. While some of South Asia’s laws on religious offence date back to the Raj, the laws relating to the Ahmadi, and the law making insulting Muhammad a capital offence only emerged in the 1980s, as part of General Zia’s attempts to shore up his religious credentials.

The sad fact is this Pakistan’s new enthusiasm for blasphemy laws is not an international aberration. Nor is this a trend confined to confessional Islamic states.

Ireland’s 2009 Defamation Act introduced a 25,000 Euro fine for the publication of “blasphemous matter”. According to the Act , “a person publishes or utters blasphemous matter if—

(a) he or she publishes or utters matter that is grossly abusive or insulting in relation to matters held sacred by any religion, thereby causing outrage among a substantial number of the adherents of that religion, and

(b) he or she intends, by the publication or utterance of the matter concerned, to cause such outrage.”

Note how similar the wording is to the Pakistani law forbidding Ahmadis from offending Muslims. The Pakistani government repaid the compliment when, along with other members of the Organisation of Islamic Conference, it attempted to force the UN to recognise “religious defamation” as a crime, lifting text from the Irish act. Pakistan claimed, grotesquely, that criminalising blasphemy was about preventing discrimination. Cast your eyes back once again to how its blasphemy provisions treat Ahmadis.

Across Europe, more and more blasphemy cases are emerging. In January of this year, a Greek man was sentenced to 10 months for setting up a Facebook page mocking an Orthodox cleric. In 2012, Polish singer Doda was fined for suggesting that the Bible read like it was written by someone drunk and “smoking some herbs”. The trial of Pussy Riot in Russia was heavy with talk of sacrilege.

We tend to believe that the world is moving inexorably toward a secular settlement. The unintended upshot of this prevalent belief is that organised religions, even in countries like Pakistan, get to portray themselves as weak people who need to be protected from extinction, even as they wield power of life and death over people.

Religious persecution is real, and should be fought. Freedom of belief is a basic right. But blasphemy laws protect only power, and never people.

This article was posted on July 31, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org