Paper refuses BNP ad

London local paper the Hackney Gazette has decided not to allow the British National Party to advertise in its pages.

(more…)

London local paper the Hackney Gazette has decided not to allow the British National Party to advertise in its pages.

(more…)

Should publications only run ads that match their principles, asks Peter Wilby

Should publications only run ads that match their principles, asks Peter Wilby

Many readers and some journalists believe editors should apply the same principles to advertising as they do to editorial copy. If an ad is violently at variance with the publication’s philosophy, they think, it should be spiked. So when I was editor of the New Statesman (1998-2005), I received frequent complaints about our accepting ads from, for example, arms manufacturers, tobacco companies, nuclear power firms, and fast, child-maiming, planet-polluting cars.

In reply, I would make several points. First, if we didn’t accept what little advertising was available to a magazine of 25,000 circulation, the impoverished New Statesman wouldn’t exist at all. Our right-wing rival, the Spectator, which appeared to think smoking, nuclear power and driving at 120mph guaranteed long life and eternal health, would be strengthened. Second, if an arms company wanted to help finance a magazine that was vehemently opposed to arms sales, why should I object? Third, it was in editorial’s interests to maintain a wall between itself and advertising. I would never trim an editorial line, or pull an article, to please an advertiser, nor would the advertising department ask me to. Equally, I wouldn’t interfere in advertising’s affairs. Fourth, providing advertisers’ activities were legal and their copy was not indecent, offensive or libellous, they were entitled to their say. To refuse an advertisement because I disliked what it was selling or the opinions it represented would be an act of censorship.

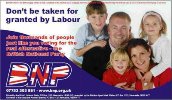

So what would I have done about an ad from the far-right British National Party, with its history of racism and anti-Semitism? This dilemma faced Geoff Martin, editor of the Hampstead & Highgate Express — which serves an area with a large Jewish population — in the run-up to the London mayoral elections. Despite protests from journalists, readers and local councillors, one of whom denounced him for the ‘shameless pursuit of profit over principle’, Martin accepted a BNP ad. However, the editor of the Hackney Gazette, part of the same group, Archant, and serving an area with a large black population, had apparently refused it. ‘The BNP,’ Martin wrote in a column in the same issue, ‘is a legally constituted political party. . . to tolerate those we vehemently disagree with is the hallmark of a truly open, egalitarian and democratic society.’