Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The central theme of the Spring 2023 issue of Index is India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

After monitoring Modi’s rule since he was elected in 2014, Index decided to look deeper into the state of free expression inside the world’s largest democracy.

Index spoke to a number of journalists and authors from, or who live in, India; and discovered that on every marker of what a democracy should be, Modi’s India fails. The world is largely silent when it comes to Narendra Modi. Let’s change that.

Can India survive more Modi?, by Jemimah Seinfeld: Nine years into his leadership the world has remained silent on Modi's failed democracy. It's time to turn up the temperature before it's too late.

The Index, by Mark Frary: The latest news from the free speech frontlines. Big impact elections, poignant words from the daughter of a jailed Tunisian opposition politician, and the potential US banning of Tik Tok.

Cultural amnesia in Cairo, by Nick Hilden: Artists are under attack in the Egyptian capital where signs of revolution are scrubbed from the street.

‘Crimea has turned into a concentration camp’, by Nariman Dzhelal: Exclusive essay from the leader of the Crimean Tatars, introduced by Ukranian author Andrey Kurkov.

Fighting information termination, by Jo-Ann Mort: How the USA's abortion information wars are being fought online.

A race to the bottom, by Simeon Tegel: Corruption is corroding the once-democratic Peru as people take to the streets.

When comics came out, by Sara Century: The landscape of expression that gave way to a new era of queer comics, and why the censors are still fighting back.

In Iran women’s bodies are the battleground, by Kamin Mohammadi: The recent protests, growing up in the Shah's Iran where women were told to de-robe, and the terrible u-turn after.

Face to face with Iran’s authorities, by Ramita Navai: The award-winning war correspondent tells Index's Mark Frary about the time she was detained in Tehran, what the current protests mean and her Homeland cameo.

Scope for truth, by Kaya Genç: The Turkish novelist visits a media organisation built on dissenting voices, just weeks before devastating earthquakes hit his homeland.

Ukraine’s media battleground, by Emily Couch: Two powerful examples of how fraught reporting on this country under siege has become.

Storytime is dragged into the guns row, by Francis Clarke: Relaxed gun laws and the rise of LGBTQ+ sentiment is silencing minority communities in the USA.

Those we must not leave behind, by Martin Bright: As the UK government has failed in its task to rescue Afghans, Index's editor at large speaks to members of a new Index network aiming to help those whose lives are in imminent danger.

Modi’s singular vision for India, by Salil Tripathi: India used to be a country for everyone. Now it's only for Hindus - and uncritical ones at that.

Blessed are the persecuted, by Hanan Zaffar: As Christians face an increasing number of attacks in India, the journalist speaks to people who have been targeted.

India’s Great Firewall, by Aishwarya Jagani: The vision of a 'digital India' has simply been a way for the authoritarian government to cement its control.

Stomping on India’s rights, by Marnie Duke: The members of the RSS are synonymous with Modi. Who are they, and why are they so controversial?

Bollywood’s Code Orange, by Debasish Roy Chowdhury: The Bollywood movie powerhouse has gone from being celebrated to being used as a tool for propaganda.

Bulldozing freedom, by Bilal Ahmad Pandow: Narendra Modi's rule in Jammu and Kashmir has seen buildings dismantled in line with people's broader rights.

Let’s talk about sex, by Mehk Chakraborty: In a country where sexual violence is abundant and sex education is taboo, the journalist explores the politics of pleasure in India.

Uncle is watching, by Anindita Ghose: The journalist and author shines a spotlight on the vigilantes in India who try to control women.

Keep calm and let Confucius Institutes carry on, by Kerry Brown: Banning Confucius Institutes will do nothing to stop Chinese soft power. It'll just cripple our ability to understand the country.

A papal precaution, by Robin Vose: Censorship on campus and taking lessons from the Catholic Church's doomed index of banned works.

The democratic federation stands strong, by Ruth Anderson: Putin's assault on freedoms continues but so too does the bravery of those fighting him.

Left behind and with no voice, by Lijia Zhang and Jemimah Steinfeld: China's children are told to keep quiet. The culture of silence goes right the way up.

Zimbabwe’s nervous condition, by Tsitsi Dangarembga: The Zimbabwean filmmaker and author tells Index's Katie Dancey-Downes about her home country's upcoming election, being arrested for a simple protest and her most liberating writing experience yet.

Statues within a plinth of their life, by Marc Nash: Can you imagine a world without statues? And what might fill those empty plinths? The London-based novelist talks to Index's Francis Clarke about his new short story, which creates exactly that.

Crimea’s feared dawn chorus, by Martin Bright: A new play takes audiences inside the homes and families of Crimean Tatars as they are rounded up.

From hijacker to media mogul, Soe Myint: The activist and journalist on keeping hope alive in Myanmar.

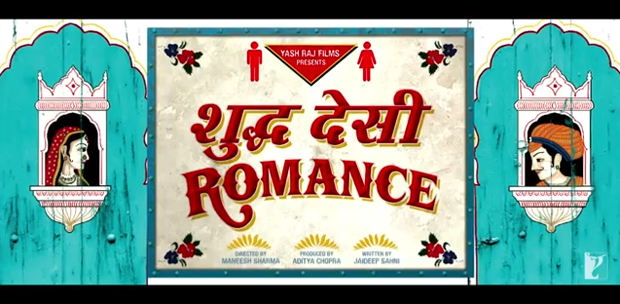

(Image: YRF/YouTube)

It an interesting introduction to his modus operandi, the new CEO of India’s censor board has described his objection to some of India’s recent blockbusters is based on the reactions of his wife and five year old daughter.

In an interview to the Mumbai Mirror, Rakesh Kumar, was quoted as saying: “After watching Shudh Desi Romance, my five-year-old daughter asked me, 'Dad, isn't there too much love in this movie?' More recently, I went to see Yaariyan with her and came out visibly embarrassed. Now, I have decided not to see even a UA film with my kid.”

Predictably, reactions were fierce. Movies with a UA rating in India are tagged for parental guidance, as they might be inappropriate for young children. These movies have mild sex scenes, gory images of violence and crude language. Kumar, a former employee of the Indian Railways, might feel "inappropriate content" is making it to the big screens, however, it only serves to highlight that the censorship of movies cannot be viewed from the perspective of a five year old girl.

Aside from the many jokes being made at Kumar’s expense, a deeper issue has been brought to the surface yet again. A constitutionally mandated body under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) regulates any films that are to be publicly exhibited. In India, there are a number of certificates a film could be given: A for Adult, UA, unrestricted public exhibition with parental guidance, S, restricted to a special class of persons, and the coveted U, which is unrestricted public exhibition, and is also the class of movies that can be shown on Indian television at prime time.

The first question many might ask is, does India need a censor board? With all kinds of content available on television and the internet, is censoring film for "inappropriate" content still valid? However, given that India does have a censor board, the next question is who it is made up of. There are about 500 members of CBFC, who preview around 13,500 films a year. The current chair is a famous dancer, Leela Samson, who controversially commented that almost 90% of her fellow board members were “uneducated political workers who did not understand their responsibility,” for which she later had to apologise. The current, and past, CEO of the board have been serving bureaucrats, on loan for this role. The final and biggest questions of the censor board faces, is how and why films are given the certifications they are.

In a very telling essay after his stint on the CBFC, journalist Mayank Shekhar wrote about the kinds of arguments that would take place at the meetings he attended: “Over the years, the focus of the Censor Board appears to have shifted from sex and violence to people’s “hurt sentiments” – some of it possibly real, but much of it imagined."

The truth is that there are three broad problems in the certification of Indian films. First, the film board censors movies based on their moral outrage to sex or violence (as exhibited by the new CEO’s reaction), fear of minority groups getting upset (as witnessed by Shekhar), and the attempt to keep films with controversial subjects like the politics of Kashmir away from the mainstream audience, often by giving them A certification (as experienced by filmmaker Ashvin Kumar and reported by Index).

The second is the approach of filmmakers. Some, in order to get their films on TV by getting a U certificate, are only too happy to oblige any cuts the board might suggest, betraying any artist integrity. The other extreme is filmmakers who put in scenes with the intention of crossing swords with the board, thereby garnering some press attention for the movie. Shekhar writes in his essay of producer who was very disappointed that the board was not cutting any of his violent scenes, pleading: “Come on, how will people know this film exists? I’ve made a very violent film. How will I publicise it?”

The third is the allegation that board members take bribes in exchange for lenient certifications, as reported by Mint. Some feel the board goes easy on big production houses. This is because there are great financial implications involved with the certification process. Filmmakers want to make their investments back, both from the box office and lucrative satellite rights should their films be picked up for prime time viewing on television channels -- as they can be with a U rating. Five Indian filmmakers have expressed their frustration with the lack of transparency in the decision making process of the CBFC, as well as perceived political interference. “I got an SMS from a senior member of a national political party, who told me that he was now with the Censor Board so to let him know if I needed any help,” revealed filmmaker Tigmanshu Dhulia.

However, ultimately, the entire argument boils down to the moral order, real or contrived, that Indian films must subscribe to should they want to be seen by the general public -- both in movie halls and at a reasonable hour on television. In 1994, the censor board asked the makers of the movie Khuddar to replace the word "sexy" in a song with the word "baby". So lyrics went like this (translated) – “baby, baby, baby, is what people call me.” In a repeat performance of a kind, in 2009, the world "sexy" was yet again replaced, but this time with "crazy" for the television version of the film. Over the years, kissing and even some sex scenes have slipped into Hindi cinema, as has a lot of cussing and plenty of violence. Nudity is only permitted in certain movies, which is either pixelated or viewed by a long-shot. Freedom of expression certainly seems in line behind the perceived notions of vulgarity of a few.

Thankfully, satire is alive and well in India, and enough websites are taking the CBFC and its new CEO to task. Others, like filmmaker Hansal Mehta, are determined to file an RTI – Right to Information – application to question every decision the board takes. As he says: “It only takes Rs 10 (under 1GBP) to file an RTI application. We live in a democracy, no one can stop me.”

This article was published on 29 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

The long arm of Chinese soft power has reached Bollywood.

Indian censors have ordered the makers of Rockstar to cut or blur scenes showing images of the Tibetan national flag, which features in one of the film’s song and dance numbers. The movie opened last Friday with the required cuts.

The controversial sequence was a crowd scene filmed at Mcleod Ganj, a hill station town in northern India and home of the Dalai Lama since he fled Lhasa in exile in 1959.

Tibetans in exile naturally are incensed and have been staging rallies. It is not clear why the flag has been banned from the romantic musical, but Indian media speculated that India is bowing to pressure from China.

Kunsang Kelden, New-York based Tibetan activist and former board member of Students for a Free Tibet, told us: “It is outrageous that a vibrant democracy such as India, with an equally vibrant film industry, should bow down to Chinese pressure, violate free speech and censor the Tibetan flag.”

Rockstar's director Imtiaz Ali may have the last laugh though.

According to Indian media his next film will be about the Tibetan independence movement.

“Reliable sources say that the movie will have political turmoil as one of the aspects along with love brewing between a Tibetan and a multi-millionaire Indian boy,” reports The Times of India.

It will be interesting to see how the censors deal with that.

The release of Amitabh Bachchan’s controversial new film, Aarakshan, which focuses on students benefiting from India’s quota system for Dalits (untouchables), has been met with protests and criticism from groups representing low-caste Hindus. Lawmakers in the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and Andhra Pradesh made an initial decision to block the release of the film, following the public’s reaction. Officials in Punjab and Andhra Pradesh decided instead to release a censored version of the feature, removing any scenes that would illicit anger from citizens. In Uttar Pradesh, the ban is still in place.