Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Bolo Bhi, which means “speak up” in Urdu, is a non-profit run by a powerful all-female team, fighting for internet access, digital security and privacy in Pakistan and around the world. Founded in 2012 by Sana Saleem and Farieha Aziz, they have since fought tirelessly to challenge Pakistan’s increasingly pervasive internet censorship.

|

|

“In the year 2012 the government were trying to bring in a national URL filtering firewall along the lines of China,” Farieha Aziz told Index.

“Then came the YouTube ban in September 2012. We lead a campaign against that and got commitments from businesses around the world not to bid for the tender the government of Pakistan had floated.”

The team have now launched countless internet freedom programmes, published research papers, fought for gender-rights, government transparency, executed successful campaigns and run digital security training sessions all over Pakistan.

“In Pakistan the internet is an unlegislated space, so a lot of our work involves discussions law and policy, and the shape they should be taking and the shape they should not be taking,” says Aziz.

Their biggest fight to date has been taking on the draconian Prevention of Electronic Crimes (PEC) Bill. The proposed legislation includes the criminalisation of political criticism and political expression in the form of analysis, commentary, blogs and cartoons, caricatures, memes; “obscene” or “immoral” messages on social media; posting of photographs of anyone on Facebook or Instagram without their permission; and sending an email or message without the recipient’s permission.

“We were able to get a leaked copy [of the bill] and we went public and we started forming an alliance,” said Aziz. “Our part was really to get people on board and collect people to collectively resist the bill in its current form.”

At every stage of the bill’s dramatic progression, Bolo Bhi been tirelessly campaigning against and shedding light on the legislation, which would have otherwise been quietly passed. They have created a timeline tracking cybercrime legislation with information on every development.

They also organised a series of press conferences, media events and campaigns to raise public awareness about the bill, as well as facilitating a series of consultations on the proposed cybercrime law with activists, lawyers and technology experts.

“Over a period of a year from advocating, trying to get the media to talk about it, we saw that a lot of people, even citizens, were very concerned about it. Across the board this concern resonated and nobody wanted the bill in the form it existed. We thought it would pass in a month, but it’s been almost a year and it’s been held off.”

Last year they also took down Pakistan’s Inter-Ministerial Committee for the Evaluation of Websites, filing a petition in the Islamabad High Court challenging the legality of committee, which is responsible for all official decisions taken to block online content in Pakistan. After a court ruling in March 2015, the IMCEW was disbanded – a win for Bolo Bhi, until the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority was given powers for content management on internet. Bolo Bhi continue to fight against the restrictions.

As well as shaping the debate around internet freedom in Pakistan, Bolo Bhi campaigns tirelessly for women’s rights.

“Gender is an integral part of what we do at Bolo Bhi. Recently we’ve tackled acid crimes, which are particularly perpetrated against women. We launched a social media campaign but we’ve also worked with women’s groups.”

Freedom of expression in Pakistan is a complicated phrase, Aziz says. But Bolo Bhi’s work ensures it is not one that is left unexamined.

Outspoken and irreverent comic and writer Shazia Mirza will host the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards Gala on 13 April.

From a journalist who trains women to tell the story of Syria’s civil war and a comedian who uses her routines to campaign for women’s rights in Indonesia, to a women-led campaigning group taking on the fight against internet censorship in Pakistan, the shortlist for the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards showcases women with leadership and bravery.

On International Women’s Day we celebrate the amazing women on our shortlist.

While many fled, Syrian-native journalist Zaina Erhaim returned to her war-ravaged country in 2013 to ensure those left behind were not forgotten. She is now one of the few female journalists braving the twin threat of violence from both IS and Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad.

While many fled, Syrian-native journalist Zaina Erhaim returned to her war-ravaged country in 2013 to ensure those left behind were not forgotten. She is now one of the few female journalists braving the twin threat of violence from both IS and Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad.

Arts nominee Sakdiyah Ma’ruf is a stand-up comedian from Indonesia whose routines challenge Islamic fundamentalism. Born to a conservative Muslim family in Java, Ma’ruf went against her father’s wishes and started using comedy to speak about religious-based violence and extremism, ethnic extremism and xenophobia, as well as fear, terror and violence against women.

Arts nominee Sakdiyah Ma’ruf is a stand-up comedian from Indonesia whose routines challenge Islamic fundamentalism. Born to a conservative Muslim family in Java, Ma’ruf went against her father’s wishes and started using comedy to speak about religious-based violence and extremism, ethnic extremism and xenophobia, as well as fear, terror and violence against women.

Artist Tania Bruguera was arrested after an attempt to stage her performance piece #YoTambienExijo in Havana in late 2014. Mounted soon after the apparent thaw in US-Cuban relations, Bruguera’s piece offered members of the public the chance of one minute of “censor-free” expression in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución.

Artist Tania Bruguera was arrested after an attempt to stage her performance piece #YoTambienExijo in Havana in late 2014. Mounted soon after the apparent thaw in US-Cuban relations, Bruguera’s piece offered members of the public the chance of one minute of “censor-free” expression in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución.

Campaigning nominee nineteen-year-old Vanessa Berhe continues to fight for the release of her uncle, journalist Seyoum Tsehaye, who has been imprisoned in Eritrea for the last 15 years. She also launched the campaign Free Eritrea to draw the world’s attention to a little-reported country with one of the worst track records for free speech.

Campaigning nominee nineteen-year-old Vanessa Berhe continues to fight for the release of her uncle, journalist Seyoum Tsehaye, who has been imprisoned in Eritrea for the last 15 years. She also launched the campaign Free Eritrea to draw the world’s attention to a little-reported country with one of the worst track records for free speech.

Lina Attalah, chief editor, is just one of the women and men — friends and journalists — who in 2013 founded an independent news collective Mada Masr after newspaper Egypt Independent was censored into bankruptcy. Mada Masr was launched as a media co-operative that aims to hold those in power accountable.

Lina Attalah, chief editor, is just one of the women and men — friends and journalists — who in 2013 founded an independent news collective Mada Masr after newspaper Egypt Independent was censored into bankruptcy. Mada Masr was launched as a media co-operative that aims to hold those in power accountable.

Bolo Bhi are a digital campaigning group who have orchestrated an impressive ongoing fight against attempts to censor the internet in Pakistan. The all-women management team have launched internet freedom programmes, published research papers, tirelessly fought for government transparency and run numerous innovative digital security training programmes.

Bolo Bhi are a digital campaigning group who have orchestrated an impressive ongoing fight against attempts to censor the internet in Pakistan. The all-women management team have launched internet freedom programmes, published research papers, tirelessly fought for government transparency and run numerous innovative digital security training programmes.

Belarus Free Theatre, co-founded by Natalia Kaliada, have been using their creative and subversive art to protest the dictatorial rule of Aleksandr Lukashenko for a decade. Despite pressure from authorities since their inception, the group thrived underground, with performances in apartments, basements and forests despite continued arrests and brutal interrogations. In 2011, while on tour, they were told they were unable to return home. Refusing to be silenced, the group set up headquarters in London and continued to direct projects in Belarus.

Belarus Free Theatre, co-founded by Natalia Kaliada, have been using their creative and subversive art to protest the dictatorial rule of Aleksandr Lukashenko for a decade. Despite pressure from authorities since their inception, the group thrived underground, with performances in apartments, basements and forests despite continued arrests and brutal interrogations. In 2011, while on tour, they were told they were unable to return home. Refusing to be silenced, the group set up headquarters in London and continued to direct projects in Belarus.

This year, the Index awards gala on 13 April will be hosted by stand-up comedian and writer Shazia Mirza, whose outspoken and taboo-busting comedy explores Islamic fundamentalism and women’s rights. Mirza is fresh from her sell-out London run and in the midst of her current UK tour.

This article was published on 8 March 2016 at indexoncensorship.org

The past few months have seen the rise of a vocal and sophisticated anti-censorship campaign in Pakistan that has effectively shamed the government into shelving its plans for a national internet filtering system.

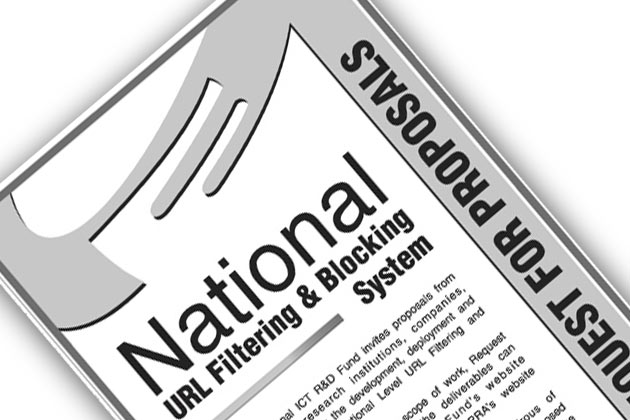

The Pakistan government’s ICT research and development fund issued a call in February for proposals from academia and companies for the development of a large-scale filter to block websites deemed “undesirable”.

According to the call, Pakistani internet service providers (ISPs) and backbone providers had “expressed their inability to block millions of undesirable web sites using current manual blocking systems.”

The document goes on to specify that the system should allow for the blocking of up to 50 million URLs with a processing delay of “not more than 1 milliseconds [sic]”. Were it to succeed, such a blanket system would put Pakistan’s internet on a par with the surveillance and filtering of China’s Great Firewall.

Human rights groups Bolo Bhi and Bytes for All have called on companies not to respond to the bid for proposals. Their methods seem to have worked, with five companies, including Websense, McAfee and Cisco saying they will not bid. Websense issued the following statement last month:

Broad government censorship of citizen access to the internet is morally wrong. We further believe that any company whose products are currently being used for government-imposed censorship should remove their technology so that it is not used in this way by oppressive governments.

The grassroots campaign has also garnered international attention, with a global coalition of NGOs, including Index, Article 19 and the Global Network Initiative, calling for the withdrawal of Pakistan’s censorship plans.

For Jillian C York, director for International Freedom of Expression at the San Francisco-based Electronic Frontier Foundation, the support of, rather than initiation by, international groups has been key. “I think that it was a combination of strong Pakistani organisations working with international organisations in tandem that made this campaign so big,” York said in an email. “Bolo Bhi and Bytes for All made the campaign a local one, using the language they preferred, but were smart enough to get the right organisations to amplify their voices while still maintaining control of the tone. I think that’s the example that they set.”

“I don’t see a company going forward with it now because there’s been public outrage and naming and shaming,” Sana Saleem, CEO of Bolo Bhi (“speak up” in Urdu), told Index. “There has been consistent effort and collaboration (…) It is tempting to shout but we said ‘let’s sit down first’. If we were reactionary it would make it hard for businesses to join us.”

In addition to appealing to companies and receiving international support, activists continued to contact the Pakistani government. Eventually a member of the National Assembly notified Bolo Bhi that the country’s secretary of IT had confirmed to her that the proposals had been shelved. Yet no official statement has been released, with Bolo Bhi and other civil society members planning to file a consititutional petition tomorrow. Saleem says the verbal commitment could be seen as a delaying tactic, arguing that now is the time to “consistently build on the campaign.”

Saleem says the Pakistani government has been looking for more control of the internet — which is accessed by 20 million of the country’s 187 million population — and that the filtering proposals could give rise to blanket surveillance. The vagueness of the terms “objectionable content” and “national security” in the terms of reference might also make the plans prone to abuse.

The proposals also threaten secure, encrypted web browsing available via https. “Something that has always annoyed intelligence agencies is not being able to access https,” Saleem said, noting that the government currently needs a court order if they wish to monitor particular users. The proposals would essentially absolve ISPs of the responsibility of blocking content manually.

Her fear is where the filtering would stop. “If we allow the state to be our moral police, it could be pornography today and something else tomorrow,” she said, citing a case late last year in which the PTA issued directives to ISPs to block 1,000 pornographic websites.

Given its apparent backtracking, Saleem predicts that the government will now be more careful in how it approaches internet filtering and surveillance. “The government made a huge mistake in making the proposals public, so they might be more covert in the future.” She adds that more controversial issues of morality and blasphemy will continue to pose a challenge in the country. “These are very charged issues,” she said, adding: “when we talk about internet freedom and freedom of expression, the government will continue to use these [issues] as a shield to exert control.”

Saleem’s aim now is to get more stakeholders involved in a broader debate about Pakistan’s national security, starting by holding discussions with university students. “Ideally we’d want the internet to be completely free, but we do know Pakistan is a police state. This is a time when we can sit down and see what we want to do.”

Marta Cooper is an editorial researcher at Index. She tweets at @martaruco.