7 May 2019 | Artistic Freedom, Brazil, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”106683″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]It should come as no surprise that, when opening an exhibition exploring queer identity, there will be critics.

In Brazil, where LGBTQI+ concerns were removed from the country’s human rights ministry’s purview earlier this year, when the death threats come in relentlessly, attitudes toward gay rights pose a significant worry — particularly when one of the people making those threats happens to be the president.

For Gaudêncio Fidelis, curator of Queermuseu, this is the crushing reality he faces. Back in 2017, Fidelis launched the exhibition celebrating queer artists. Applauded by the creative community, it was soon shuttered after a backlash from the religious right – amongst them now-President Jair Bolsonaro, who at the time was a federal deputy for Rio de Janeiro.

“Bolsonaro said I should be killed when he was not even a candidate, just a few hours after Queermuseu was shut down,” said Fidelis. “He didn’t mention my name because he didn’t know it, I guess. He referred to me as the ‘author of that exhibition’.

“In the first two months I got more than 100 death threats to a point where I had to have security, I had to be careful. Very few people I know, and I know some brave people, could handle that situation. I never slept for a year.”

One of Fidelis’ main detractors were far-right group Free Brazil Movement (MBL), who attacked Queermuseu persistently for two days during its opening. MBL alleged the exhibition, which included 214 works from 82 artists, promoted paedophilia, zoophilia and blasphemy, subsequently leading to its closure.

“They took the painting of two teenagers having sex with a goat, but this is a painting about people’s habits and the colonisation of Brazil,” Fidelis said. “They cropped this image and put it on the internet as if it was the picture. They were also putting up pictures that were not in the exhibition. A lot of fake news.”

In the aftermath of its sudden demise, Queermuseu drew support from artists and academics, leading to more than 3,500 people to protest outside the Santander Cultural centre in Porto Alegre, which is owned by the Santander bank.

“It turned into a huge campaign of not only reopening the exhibition, but in favour of free expression and human rights, because people’s rights were attacked,” he said. “It was not just an attack against the exhibition, it was a whole campaign against free expression.

“It was the largest ever protest in Brazil in the field of art and culture. This became a very contemptuous debate, or fight you could say – it was an intense battle that lasted for more than 12 months.”

However, Fidelis says what followed was one of the most successful crowdfunding campaigns in Brazil, raising over $1 million. Fidelis said he was even more surprised by the the mainstream media, which backed his campaign, allowing him to counter the fake news around the exhibition.

“I’ve never seen that with the press, they always keep some critical distance,” he said. “They were engaged throughout the process in defending the exhibition. The press understood that they would be next to be attacked, and that’s what happened two months later.”

After a visit from the public prosecutor’s office, who declared the defamatory allegations made against Queermuseu to be false, the exhibition was officially reopened to the public in 2018. Despite his success, Fidelis remains fearful for the future of free expression in his country – particularly for queer people.

Bolsonaro removed LGBTQI+ concerns from Brazil’s human rights ministry in January, while openly gay congressman Jean Wyllys quit his position and left the country later that month. He explained how he had been inundated with death threats and that violence had increased since Bolsonaro’s election.

“We were in plain democracy, so much so, that we could appeal to the Supreme Court – I did it twice,’ said Fidelis. “We could go to the normal institutions of democracy, but we can’t do that now. It’s a whole new world in Brazil and that’s why people are leaving.” [/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1557304208972-adcd0337-5d35-7″ taxonomies=”15469″ exclude=”105410, 105403, 105408, 105400″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Jan 2018 | Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico, News, Venezuela

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Latin America is home to a growing number of independent publications, like Venezuela’s Efecto Cocuyo, that do not depend on government advertising

With general elections scheduled in six Latin American countries this year, and another six to follow in 2019, the relationship between the media and democracy could have a major impact on the future of the region. However, mounting financial pressures are robbing many media outlets of their objectivity and forcing them to toe pro-government lines.

With traditional advertising revenue in decline, Latin American governments are using vast publicity budgets to keep cash-strapped publications afloat. In return, the media are expected to portray their benefactors in a favourable light.

According to the NGO Freedom House, much of the media in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras and Mexico is heavily dependent on government advertising, resulting in widespread self-censorship and collusion between public officials, media owners and journalists.

“The history of journalism in Latin America is a history of collusion between the press and powerful people,” said Rosental Alves, a Brazilian journalist and founder of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, in an interview with Index. Sections of the media have become subservient, he explained, as any critical coverage could be punished with audits or a loss of advertising revenue.

Financial pressures on the media are particularly pronounced in Venezuela. Alves observed that the Nicolás Maduro regime has applied “waves of censorship” to the media by first decrying it as “the enemy of the people” and then buying up media companies to “make them friendly.”

Freedom House notes that “although privately owned newspapers and broadcasters operate alongside state outlets, the overall balance has shifted considerably toward government-aligned voices in recent years. The government officially controls 13 television networks, dozens of radio outlets, a news agency, eight newspapers, and a magazine.”

This is compounded by Venezuela’s severe economic problems and the virtual government monopoly on newsprint supplies that have led to newspaper closures, staff cutbacks and reduced circulation of critical media.

Mexico’s government has taken the more subtle approach of co-opting swathes of the media through unprecedented expenditure on advertising. According to the transparency group Fundar, President Enrique Peña Nieto has spent almost £1.5 billion on advertising in the past five years, more than any president in Mexican history. On top of that, state and municipal administrations have also spent millions on publicity in local media.

Darwin Franco, a freelance journalist in Guadalajara, told Index that government spending has led to some publications telling reporters “who they can and cannot criticise in their work.”

Then there is the infamous chayote, a local term for bribes paid to journalists in return for favourable coverage. Franco said Mexican reporters are particularly vulnerable to economic pressures or under-the-table incentives because it’s so hard for them to make a living.

“Freelance journalists in Mexico don’t receive the benefits that employees are legally entitled to,” he said. “National media outlets — and even some international ones — pay us minimal fees for stories, which in some cases don’t even cover the costs of reporting.”

Franco, who also teaches journalism at a local university, added that many reporters take on second jobs to supplement their income. With Mexican journalists making less than £450 per month on average, he acknowledged that “there may be people who are tempted” to take money from the government.

Despite these financial pressures, Alves is encouraged by the technology-driven democratisation of the media across Latin America, with increased internet penetration and the affordability of smartphones allowing people who could not afford computers to access nontraditional media for the first time.

These include rudimentary blogs, social media accounts and more sophisticated media startups, Alves said, with countries like Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and even Venezuela home to a growing number of independent publications that do not depend on government advertising.

“We are living a time of the decline of advertisements as the main source of revenue for news organisations. On the one hand you have this huge decline in traditional advertising because of Google and Facebook getting all this money, and on the other hand you see the virtual disappearance of the entry barriers for becoming a media outlet,” Alves noted.

“We’re moving from the mass media to a mass of media because there’s this proliferation of media outlets that don’t depend on a lot of money,” he added. “If you can gather some philanthropic support or membership, or you’re just doing it by yourself, like many courageous bloggers are doing in many parts of the region, you don’t make any money but you don’t spend any money either.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Survey: How free is our press?” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fsurvey-free-press%2F|title:Take%20our%20survey||”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-pencil-square-o” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

This survey aims to take a snapshot of how financial pressures are affecting news reporting. The openMedia project will use this information to analyse how money shapes what gets reported – and what doesn’t – and to advocate for better protections and freedoms for journalists who have important stories to tell.

More information[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”97191″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/01/tracey-bagshaw-compromise-compromising-news/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Commercial interference pressures on the UK’s regional papers are growing. Some worry that jeopardises their independence.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”81193″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/jean-paul-marthoz-commercial-interference-european-media/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Commercial pressures on the media? Anti-establishment critics have a ready-made answer: of course, journalists are hostage to the whims of corporate owners, advertisers and sponsors. Of course, they cannot independently cover issues which these powers consider “inconvenient”.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96949″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.opendemocracy.net/openmedia/mary-fitzgerald/welcome-to-openmedia”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Forget fake news. Money can distort media far more disturbingly – through advertorials, and through buying silence. Here’s what we’re going to do about it.

This article is also available in Dutch | French | German | Hungarian | Italian |

Serbian | Spanish| Russian[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1515148254502-253f3767-99a5-8″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Apr 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016 Extras

Kemel Aydogan’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Turkey. Credit: Mehmet Çakici

Hitler was a Shakespeare fan; Stalin feared Hamlet; Othello broke ground in apartheid-era South Africa; and Brazil’s current political crisis can be reflected by Julius Caesar. Across the world different Shakespearean plays have different significance and power. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, a Shakespeare special to mark the 400th anniversary of his death, takes a global look at the playwright’s influence, explores how censors have dealt with his works and also how performances have been used to tackle subjects that might otherwise have been off limits. Below some of our writers talk about some of the most controversial performances and their consequences.

(For the more on the rest of the magazine, see full contents and subscription details here.)

Kaya Genç on A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream in Turkey

“When Turkish poet Can Yücel translated A Midsummer’s Night Dream, he saw the potential to reflect Turkey’s authoritarian climate in a way that would pass under the radar of the military intelligence’s hardworking censors. Like lovers in Shakespeare’s comedy who are tricked by fairies into falling in love with characters they actually dislike, his adaptation [which was staged in 1981 and led to the arrests of many of the actors] drew on the idea that Turkey’s people were forced by the state to love the authority figures that oppressed them the most. They were subjugated by the military patriarchy, the same way the play’s female and artisan characters were subjugated by Athenian patriarchy.

Kemal Aydoğan, the director of the latest Turkish adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, described the work as ‘one of the most political plays ever written’. For Aydoğan, the scene in which the Amazonian queen Hippolyta is subjugated and taken hostage by the Theseus marks a turning point in the play. ‘That Hermia is not allowed to marry the man she loves but has to wed the man assigned to her by her father is another sign of women’s subjugation by men,’ he said. This, according to Aydoğan, is sadly familiar terrain for Turkey where women are frequently told by male politicians to know their place, keep silent and do as they are told.’ ”

Claire Rigby on Julius Caesar in Brazil

“In a Brazil seething with political intrigue, in which the impeachment proceedings currently facing President Dilma Rousseff are just the most visible tip of a profound turbulence which has gripped the country since her re-election in October 2014, director Roberto Alvim’s 2015 adaptation of Julius Caesar was inspired by a televised presidential debate he saw in the final days of the election campaign, in which centre-left Rousseff faced off against her centre-right opponent Aécio Neves. ‘I watched the debate as it became utterly polarised between Dilma and Aécio, and the famous clash between Mark Antony and Brutus instantly came to mind,’ he said. ‘It was the idea that the same facts can be drawn in such completely different ways by the power of speech: the power of the word to reframe the facts, and its central importance in the political game.’ ”

György Spiró on Richard III in Hungary

“Richard III was staged in Kaposvár, which had Hungary’s very best theatre at the time. This was 1982.

Charges were brought against the production, because the Earl of Richmond wore dark glasses. A few weeks earlier, on 13 December 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared a state of emergency in Poland. For health reasons he wore sunglasses every time he appeared in public.”

Simon Callow on Hamlet under Stalin and the Nazis

“In 1941, Joseph Stalin banned Hamlet. The historian Arthur Mendel wrote: ‘The very idea of showing on the stage a thoughtful, reflective hero who took nothing on faith, who intently scrutinized the life around him in an effort to discover for himself, without outside ‘prompting,’ the reasons for its defects, separating truth from falsehood, the very idea seemed almost ‘criminal’.’ Having Hamlet suppressed must have been a nasty shock for Russians: at least since the times of novelist and short story writer Ivan Turgenev, the Danish Prince had been identified with the Russian soul. Ten years earlier, Adolf Hitler had claimed the play as quintessentially Aryan, and described Nazi Germany as resembling Elizabethan England, in its youthfulness and vitality (unlike the allegedly decadent and moribund British Empire). In his Germany, Hamlet was reimagined as a proto-German warrior. Only weeks after Hitler took power in 1933 an official party publication appeared titled Shakespeare – A Germanic Writer.”

Natasha Joseph on Othello in South Africa

“In 1987, actress and director Janet Suzman decided to stage Othello in her native South Africa, bringing ‘the moor of Venice’ to life at Johannesburg’s iconic Market Theatre. It was just two years since Prime Minister PW Botha had repealed one of apartheid’s most reviled laws, the Immorality Act, which banned sexual relationships between people of different races. Even without the legislation, many white South Africans baulked at the idea of interracial desire. No wonder, then, that Suzman’s production attracted what she has described as ‘millions of bags full of hate letters from people who thought that this was an outrage’.

But in a country famous for sweeping censorship and restrictions on freedom of movement, speech and association, the play was not banned. Why? Because the apartheid government ‘would have been the laughing stock of the world if they had banned Shakespeare’, Suzman told Index on Censorship. ‘Any government would be really embarrassed to ban Shakespeare. The apartheid government was frightened of ridicule. Everyone is frightened of laughter.’ ”

For more articles on Shakespeare’s battle with power around the world, see our latest magazine. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year, with a free trial). Copies are also available in excellent bookshops including at the BFI, Mag Culture and Serpentine Gallery (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon or a digital magazine on exacteditions.com. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

12 Feb 2016 | mobile, News, Youth Board

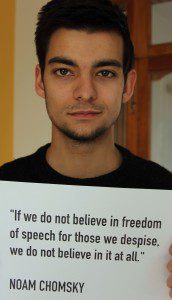

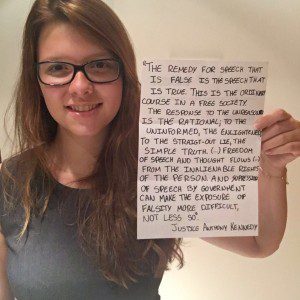

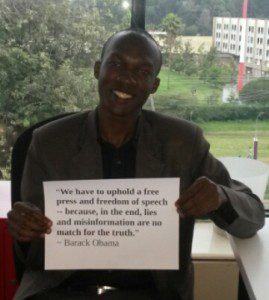

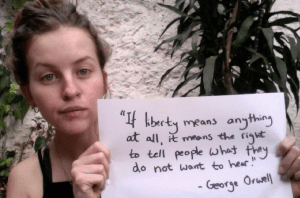

Index on Censorship recently appointed a new youth advisory board who attend monthly online meetings to discuss current freedom of expression issues and complete related tasks. As their first assignments they were asked to provide a short bio to introduce themselves, along with a photograph of them holding a quotation highlighting what free expression means to them.

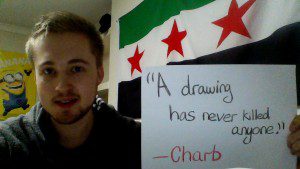

Simon Engelkes

I am from Berlin, Germany, where I study political science at Free University Berlin. I have worked as an intern with Reporters Without Borders and RTL Television, which made me passionate about the importance of freedom of speech.

I believe that freedom of expression forms an important cornerstone of any effective democracy. Journalists and bloggers must live without fear and without interference from state or economic interests. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Journalists, authors and everyday citizens are imprisoned or killed by radicals, state agencies or drug cartels. Raif Badawi, James Foley, Khadija Ismayilova, Avijit Roy – the list is endless.

We need to remind ourselves and the powerful of today, that freedom of expression as well as freedom of information are basic human rights, which we have to defend at all costs.

Mariana Cunha e Melo

Mariana Cunha e Melo

I am from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I graduated from law school in Rio and I have a degree from New York University School of Law. My family has taught me about the dangers of censorship and dictatorship, so I have always been interested in studying civil rights. This was the main reason I decided to study law.

I grew up listening to stories about the media censorship in Brazil during the military dictatorship. The fight against the ghost of state censorship has always sounded very natural to me – and, I believe, to all my generation. When I finished law school I found out that the new villain my generation has to face is the censorship based on constitutional values. The argument has changed, but the censorship is not all that different. So I decided to dedicate my academic and my professional life as a lawyer to fight all sorts of institutionalised censorship in Brazil.

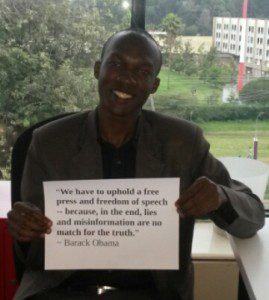

Ephraim Kenyanito

Ephraim Kenyanito

I was born and raised in Kenya, and I am currently working as the sub-Saharan Africa policy analyst at Access Now, an international organisation that defends and extends the digital rights of users at risk around the world. My role involves working on the connection between internet policy and human rights in African Union member countries. I am an affiliate at the Internet Policy Observatory (IPO) at the Center for Global Communication Studies, University of Pennsylvania. I also currently serve as a member of the UN Secretary General’s Multi-stakeholder Advisory Group on internet governance.

The reason why I have always been passionate about protecting the open internet is that it is a cornerstone for advancing free speech in the post-millennium era and there is a great need to build common ground around a public interest-oriented approach to internet governance.

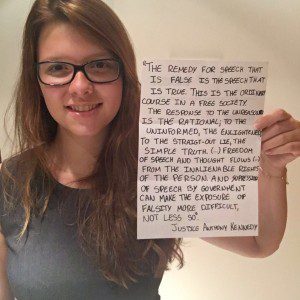

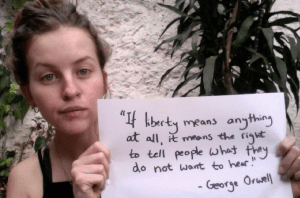

Emily Wright

I grew up in Portugal, and I am now based between London and Bogotá, Colombia. I am a freelance filmmaker and journalist. Working in documentary production and community-based, participatory journalism informed a growing interest in journalistic practices, freedom of expression and access to information.

I believe that one of the greatest threats to freedom of expression is the flagrant violation of civil liberties under the banner of national security. The war on terror, underscored by Bush’s declaration “You’re either for us or against us”, has collapsed the middle ground, suppressing any struggles that challenge that statement. Freedom of expression has become a pretext for silencing those who have the least access to it; those who do not fall in line with the global order’s supposed defence of freedom against barbarism and obscurantism.

Mark Crawford

Mark Crawford

I’m originally from Birmingham, and now a postgraduate student at University College London, specialising in Russian and post-Soviet politics. This has inevitably educated me on the pressures exerted upon freedom of expression in Russia, whose suffocated and disenfranchised opposition journalists I am currently investigating.

Hostility to free expression has become a staple of my university life. Rather than developing a coherent set of ideologies to challenge toxic values in the open, it has become mainstream for students of the most privileged universities in the world to veto them on behalf of everyone else, no-platforming and deriding free speech.

I am convinced that there is no point fighting for an egalitarian society if any monopolies over truth are permitted. Freedom of speech is, therefore, something I am keen to promote in whatever small way I can.

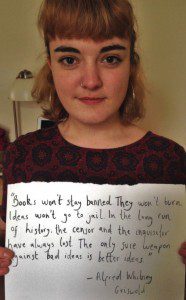

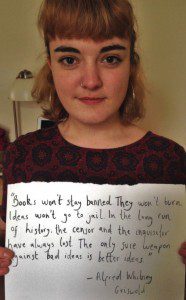

Madeleine Stone

My home is in south-east London but I spend most of my time in York, studying for my bachelor’s degree in English and related literature. I am currently the co-chair of York PEN, the University of York’s branch of English PEN, and a founding member of the Antione Collective, a human rights-focused theatre company.

Studying literature from across the globe has introduced me to issues of freedom and censorship, and the devastating effects censorship can have on national progress. Freedom of expression on campuses is hugely important to me as a student and it is currently under threat. Well-meaning individuals are shutting down the open debate that is vital to academic institutions. The only way to fight harmful ideas is to engage them head-on and destroy them through academic debate, not to ban them.

Layli Foroudi

I am a journalist and student currently studying for a MPhil in race, ethnicity and conflict at Trinity College Dublin. It was studying literary works from the Soviet period during my undergraduate degree in Russian and French at University College London that initially highlighted the issue of censorship for me. The quote I selected, “manuscripts don’t burn”, is from the book Master and Margarita by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. He wrote about the hardship that many writers faced as they had to adjust their own writing in accordance with the authority, as well as the fact that not all that is written can be taken to be true.

I think that these themes are very relevant today. Whether people are censored or self-censor out of fear of punishment or of being wrong, limiting freedom of expression results in loss of debate, of exchange and of creativity. Being denied freedom of expression is being denied the right to participation in society.

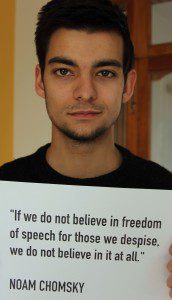

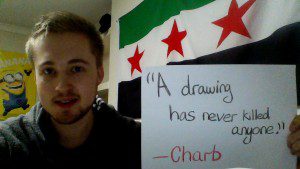

Ian Morse

Ian Morse

I have been involved in journalism since I began studying at Lafayette College, Pennsylvania, USA, and have been engaged in press freedom and reporting in three countries since then. I studied in Turkey last spring, where I interviewed and wrote about journalists and press freedom. It motivated me to begin researching and writing on my own about these topics. Now, as I study for a semester in Cambridge in the UK, I continue to talk about and advocate for free speech and press.

I find it absolutely amazing the power words and information can have in a society. It becomes then extremely damaging to realise that some things cannot be published because they conflict with those in power. Free speech is now becoming a hot topic around the world, particularly among youth, and it makes it all the more important to be able to approach freedom of expression critically and objectively.

Mariana Cunha e Melo

Mariana Cunha e Melo  Ephraim Kenyanito

Ephraim Kenyanito

Mark Crawford

Mark Crawford

Ian Morse

Ian Morse