Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Index on Censorship condemns the sentencing to four years in prison of Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi and calls for all charges to be dropped. She was convincted of incitement and also of breaking Covid regulations during the campaign for the election last year.

It is the first of eleven charges she faces which, if convicted on all counts, could mean she spends the rest of her life behind bars. Suu Kyi has been under house arrest since a military coup in the country in February 2021.

UK foreign secretary Liz Truss has expressed her concerns that “the arbitrary detention of elected politicians only risks further unrest”.

While Suu Kyi has attracted criticism for her silence over the Rohingya genocide she remains a respected political figure who won the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize for her non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights in the country. Before her current house arrest, Suu Kyi was state counsellor of Myanmar, similar to the role of prime minister in the UK, and also as minister of foreign affairs, roles she took on in 2016.

Suu Kyi has also been a frequent contributor to Index on Censorship over the years, including in March 1996, just after her release from a previous period of house arrest.

At the time, she wrote: “The regaining of my freedom has in turn imposed a duty on me to work for the freedom of other women and men in my country who have suffered far more – and who continue to suffer far more – than I have.”

In an article in 2012, she wrote about taking responsibility for the words we say.

“Can freedom of speech be abused? Since historical times it has been recognised that words can hurt as well as heal, that we have a responsibility to use our verbal skills in the right way”, she wrote.

The Autumn issue of Index magazine focuses on the struggle for environmental justice by indigenous campaigners. Anticipating the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), in Glasgow, in November, we’ve chosen to give voice to people who are constantly ignored in these discussions.

Writer Emily Brown talks to Yvonne Weldon, the first aboriginal mayoral candidate for Sydney, who is determined to fight for a green economy. Kaya Genç investigates the conspiracy theories and threats concerning green campaigners in Turkey, while Issa Sikiti da Silva reveals the openly hostile conditions that environmental activists have been through in Uganda.

Going to South America, Beth Pitts interviews two indigenous activists in Ecuador on declining populations and which methods they’ve been adopting to save their culture against the global giants extracting their resources.

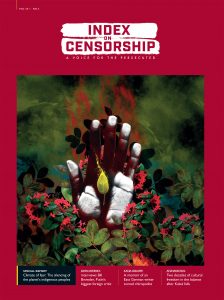

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

A climate of fear, by Martin Bright: Climate change is an era-defining issue. We must be able to speak out about it.

The Index: Free expression around the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern.

Pile-ons and censorship, by Maya Forstater: Maya Forstater was at the heart of an employment tribunal with significant ramifications. Read her response the Index’s last issue which discussed her case.

The West is frightened of confronting the bully, by John Sweeney: Meet Bill Browder. The political activist and financier most hated by Putin and the Kremlin.

An impossible choice, by Ruchi Kumar: The rapid advance of Taliban forces in Afghanistan has left little to no hope for journalists.

Words under fire, by Rachael Jolley: When oppressive regimes target free speech, libraries are usually top of their lists.

Letters from Lukashenka’s prisoners, by Maria Kalesnikava, Volha Takarchuk, Aliaksandr Vasilevich and Maxim Znak: Standing up to Europe’s last dictator lands you in jail. Read the heartbreaking testimony of the detained activists.

Bad blood, by Kelly Duda: How did an Arkansas blood scandal have reverberations around the world?

Welcome to hell, by Benjamin Lynch: Yangon’s Insein prison is where Myanmar’s dissidents are locked up. One photojournalist tells us of his time there.

Cartoon, by Ben Jennings: Are balanced debates really balanced? Ask Satan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report” font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:22|text_align:left”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Credit: Xinhua/Alamy Live News

It’s not easy being green, by Kaya Genç: The Turkish government is fighting environmental protests with conspiracy theories.

It’s in our nature to fight, by Beth Pitts: The indigenous people of Ecuador are fighting for their future.

Respect for tradition, by Emily Brown: Australia has a history of “selective listening” when it comes to First Nations voices. But Aboriginal campaigners stand ready to share traditional knowledge.

The write way to fight, by Liz Jensen: Extinction Rebellion’s literary wing show that words remain our primary tool for protests.

Change in the pipeline? By Bridget Byrne: Indigenous American’s water is at risk. People are responding.

The rape of Uganda, by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Uganda’s natural resources continue to be plundered.Cigar smoke and mirrors, by James Bloodworth: Cuba’s propaganda must not blight our perception of it.

Denialism is not protected speech, by Oz Katerji: Should challenging facts be protected speech?

Permissible weapons, by Peter Hitchens: Peter Hitchens responds to Nerma Jelacic on her claims for disinformation in Syria.

No winners in Israel’s Ice Cream War, by Jo-Ann Mort: Is the boycott against Israel achieving anything?

Better out than in? By Mark Glanville: Can the ancient Euripides play The Bacchae explain hooliganism on the terraces?

Russia’s Greatest Export: Hostility to the free press, by Mikhail Khordokovsky: A billionaire exile tells us how Russia leads the way in the tactics employed to silence journalists.

Remembering Peter R de Vries, by Frederike Geeerdink: Read about the Dutch journalist gunned down for doing his job.

A right royal minefield, by John Lloyd: Whenever one of the Royal Family are interviewed, it seems to cause more problems.

A bulletin of frustration, by Ruth Smeeth: Climate change affects us all and we must fight for the voices being silenced by it. Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

The man who blew up America, by David Grundy: Poet, playwright, activist and critic Amiri Baraka remains a controversial figure seven years after his death.

Suffering in silence, by Benjamin Lynch and Dr Parwana Fayyaz The award-winning poetry that reminds us of the values of free thought and how crucial it is for Afghan women.

Heart and Sole, by Mark Frary and Katja Oskamp: A fascinating extract gives us an insight into the bland lives of some of those who did not welcome the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Secret Agenda, by Martin Bright: Reforms to the UK’s Official Secret Act could create a chilling effect for journalists reporting on information in the public interest.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116336″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]The new military junta in Myanmar is continuing to assault and jail journalists as it progresses with its bloody coup.

At least 26 journalists have been arrested since Min Aung Hlaing seized power on 1 February and at least ten have been charged under section 505(a) of Myanmar’s penal code.

Two of the journalists, MCN TV News reporter Tin Mar Swe and The Voice’s Khin May San, have been granted bail but the remaining eight are still detained in the notorious military-run Insein prison in Yangon, known as “the darkest hell-hole” in the country and a byword for torture, abuse and inhumane conditions for inmates.

Section 505(a) makes it a crime to publish any “statement, rumour or report”, “with intent to cause, or which is likely to cause, any officer, soldier, sailor or airman, in the Army, Navy or Air Force to mutiny or otherwise disregard or fail in his duty”, essentially making criticism of the military government impossible.

Reporters are particularly vulnerable during protests. Myo Min Htike, former secretary of the Myanmar Journalist Association, recently told Index that journalists are being targeted across the country, particularly if they have covered protests against the coup and many have fled in fear for their lives and liberty.

Credible reports from the country show the dangers facing reporters covering the protests. Shin Moe Myint, a 23-year-old freelance photo journalist was severely beaten and arrested by policemen while she covered a protest in Yangon on 28 February.

Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB) journalist Ko Aung Kyaw live-streamed a violent arrest in which, according to reports by The Irrawaddy, he had stones thrown through his window and police officers firing threateningly into the air when asked if they had obtained a warrant to enter his premises.

Aung Kyaw could “be heard shouting that a stone injured his head and appealing to neighbours for help before the security forces broke into his house and arrested him”.

Thein Zaw, covering the protests for Associated Press, has been charged with violating public law while Ma Kay Zon Nway of Myanmar Now and Aung Ye Ko of 7 Days News have also been arrested.

Others still detained include the journalists Hein Pyae Zaw, Ye Myo Khant, Ye Yint Tun, Chun Journal chief editor Kyaw Nay Min and Salai David of Chinland Post.

Sit Htet Aung of the Myanmar Times, who took the picture above, was one of the lucky ones who managed to escape a beating and detention.

Use of section 505(a) shows an automatic crackdown on criticism of the military regime and since the coup, the junta has implemented a number of problematic legislation changes which could easily be used against journalists in the country.

According to Amnesty International: “Courts routinely convict individuals under this section without evidence establishing the requisite intent or a likelihood that military personnel would abandon their duty as a result of the expression.”

“In practice, the section has often been used to prosecute criticism of the military – expression protected by international human rights law.”

The law has since been amended, meaning anyone charged under it can be arrested without a warrant and it is no longer a bailable offence, thus any future arrests – which are likely – will find journalists in Myanmar detained with little hope of an immediate reprieve.

The same amendments apply to 124(a) of the penal code, which previously made anti-government comments illegal.

Journalists also rely heavily on the internet to publish their stories, but amendments to the Electronic Transactions Law allow law enforcement to harvest the personal data of anyone deemed to be in breach of a cyber-crime, or – more broadly – those critical of the regime online.[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”38″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116235″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Journalists are facing increasingly difficult circumstances in reporting what is happening as Myanmar’s new regime attempts to tighten its grip on the power it took from a democratically elected government at the start of the month.

Myo Min Htike, former secretary of the Myanmar Journalist Association, has told Index that journalists are being targeted across the country, particularly if they have covered protests against the coup.

In Mandalay, two journalists were pursued by special branch after they had covered a pro-democracy demonstration, he said.

The editor of an online publication is on the run from military intelligence and has gone into hiding, although the association’s regional safety coordinator thinks his mobile is being tapped and fears for his safety.

Journalists from Myanmar Now, DVB and RFA are all being threatened with arrest if they are not in hiding, he added.

Some local media in Rakhine and Kachin state are closing down while others have asked some reporters to stay away from newsrooms.

One of the biggest concerns is that the internet will be shut down. In the Saging region, mobile internet has been cut off today and there are rumours of a wider shutdown in the next few days.

On 11 February, Frontier Myanmar told the story of a freelance reporter who had gone to take photos of soldiers stationed between the towns of Muse and Namhkam in northern Shan State.

“They chased after him, and hit him in the chest with the barrel of a gun,” said Sai Mun, an editor at the Shan Herald Agency for News.

“When he fell to the ground, they smashed the mobile phone he was taking photos with. They told him he couldn’t take photos, and said he could be killed if he did,” said Sai Mun.

On 9 February, Mizzima journalist Than Htike Aung was hit by rubber bullets fired by police. Mizzima TV is one of two TV news channels that has been ordered off the air.

Another journalist was set upon by a nationalist mob in support of the coup.

In response to the conditions journalists in Myanmar are being forced to work under, the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) released a statement saying the violence had “dire implications for freedom of expression”.

“The reports of violence and suppression of protests have dire implications for freedom of expression and the right to peaceful assembly,” they said. “The IFJ stands in full solidarity with our journalist and media colleagues as well as all citizens of Myanmar protesting the military imposition of power and calling for an immediate return to democracy.”

Freedom to protest and the freedom to report on those protests by journalists are often the first things to be restricted in the event of a military coup and this familiar pattern has been repeated since the Myanmar coup took place on 1 February.

It came after military leader Min Aung Hlaing alleged that the landslide victory of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) in November was fraudulent, without providing evidence. On 9 February, NLD’s offices were raided by soldiers.

Written into Myanmar’s constitution is the right to assemble peacefully and – with protests against the coup continuing – the new administration has taken steps to prevent this from happening.

Under the state of emergency, the military regime has banned meetings of more than five people in one place, but Myanmar’s citizens have already begun to defy the ruling.

In response the military regime has used water cannons, rubber bullets and tear gas on protestors and there are reports of the use of live bullets in the capital of Naypyidaw.

It is against this backdrop that Min Aung Hlaing’s regime has targeted the media but the new leader and his allies hardly have a glowing record when it comes to dealing with media and journalists.

In 2019, journalist Swe Win was shot in what appeared to be a targeted attack. Not long before, he had published an article revealing the business interests of Min Hlaing which had apparently “infuriated the top”.

Last year, Khaing Mrat Kyaw, editor of Narinjara News, and Nay Myo Lin, the editor-in-chief of the Mandalay-based Voice of Myanmar, were charged with terrorism offences for carrying interviews with the insurgent Arakan Army. Kyaw Linn, a reporter with Myanmar Now, was attacked with rocks in May by unidentified assailants; he has frequently reported on the conflict between Myanmar’s military forces and the Arakan Army.

Looking forward, journalists are already fearful of existing legislation that may be used against them by the new regime, such as the Counter-Terrorism Law and also charges of defamation under the Telecommunications Law.

A proposed new Cyber Security Law demands all internet service providers to give up data stored on citizens at the government’s request.

Significantly, those deemed to be spreading “misinformation” online could face up to three years in jail, a clear violation of free speech.

The regime’s early days and the steps towards new and highly consequential legislation has journalists in the country uneasy.

Speaking to the Columbia Journalism Review, the shot journalist Swe Win said, “Even though I foresaw the coup, I did not foresee the brutal way it would be launched.”

“Within five hours of the coup, I ordered all my colleagues to leave their houses and stay somewhere with their families or their friends. Half of the team did not want to accept my idea because they were outraged, as equally as members of the public. “‘Why should we leave? We’ve got to do what we’ve got to do.’”

Additional reporting by associate editor Mark Frary.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”5641″][/vc_column][/vc_row]