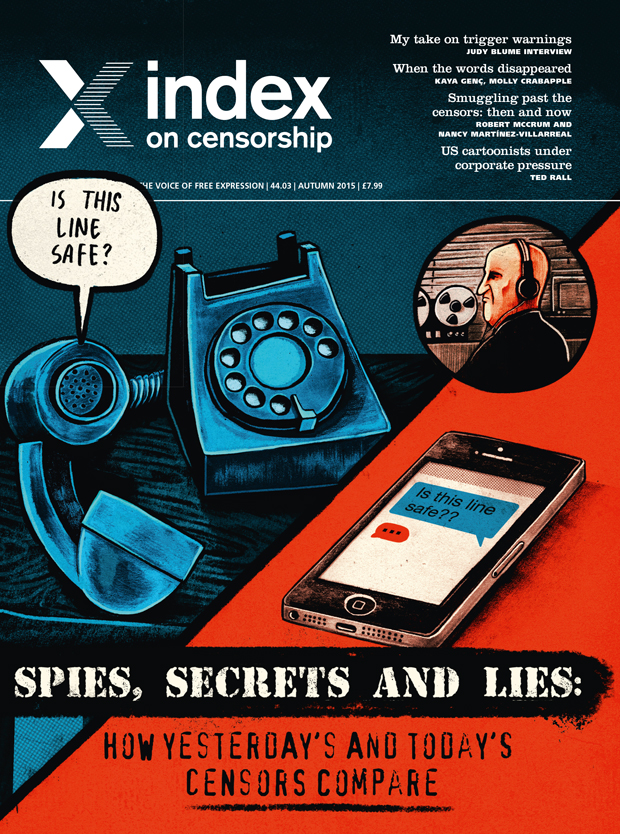

Editorial: Spies in the new machines

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

Post-Soviet Union, after the fall of the Berlin wall, after the Bosnian war of the 1990s, and after South Africa’s apartheid, the world’s mood was positive. Censorship was out, and freedom was in.

But in the world of the new censors, governments continue to try to keep their critics in check, applying pressure in all its varied forms. Threatening, cajoling and propaganda are on one side of the corridor, while spying and censorship are on the other side at the Ministry of Silence. Old tactics, new techniques.

While advances in technology – the arrival and growth of email, the wider spread of the web, and access to computers – have aided individuals trying to avoid censorship, they have also offered more power to the authorities.

There are some clear examples to suggest that governments are making sure technology is on their side. The Chinese government has just introduced a new national security law to aid closer control of internet use. Virtual private networks have been used by citizens for years as tunnels through the Chinese government’s Great Firewall for years. So it is no wonder that China wanted to close them down, to keep information under control. In the last few months more people in China are finding their VPN is not working.

Meanwhile in South Korea, new legislation means telecommunication companies are forced to put software inside teenagers’ mobile phones to monitor and restrict their access to the internet.

Both these examples suggest that technological advances are giving all the winning censorship cards to the overlords.

But it is not as clear cut as that. People continually find new ways of tunnelling through firewalls, and getting messages out and in. As new apps are designed, other opportunities arise. For example, Telegram is an app, that allows the user to put a timer on each message, after which it detonates and disappears. New auto-encrypted email services, such as Mailpile, look set to take off. Now geeks among you may argue that they’ll be a record somewhere, but each advance is a way of making it more difficult to be intercepted. With more than six billion people now using mobile phones around the world, it should be easier than ever before to get the word out in some form, in some way.

When Writers and Scholars International, the parent group to Index, was formed in 1972, its founding committee wrote that it was paradoxical that “attempts to nullify the artist’s vision and to thwart the communication of ideas, appear to increase proportionally with the improvement in the media of communication”.

And so it continues.

When we cast our eyes back to the Soviet Union, when suppression of freedom was part of government normality, we see how it drove its vicious idealism through using subversion acts, sedition acts, and allegations of anti-patriotism, backed up with imprisonment, hard labour, internal deportation and enforced poverty. One of those thousands who suffered was the satirical writer Mikhail Zoshchenko, who was a Russian WWI hero who was later denounced in the Zhdanov decree of 1946. This condemned all artists whose work didn’t slavishly follow government lines. We publish a poetic tribute to Zoshchenko written by Lev Ozerov in this issue. The poem echoes some of the issues faced by writers in Russia today.

And so to Azerbaijan in 2015, a member of the Council of Europe (a body described by one of its founders as “the conscience of Europe”), where writers, artists, thinkers and campaigners are being imprisoned for having the temerity to advocate more freedom, or to articulate ideas that are different from those of their government. And where does Russia sit now? Journalists Helen Womack and Andrei Aliaksandrau write in this issue of new propaganda techniques and their fears that society no longer wants “true” journalism.

Plus ça change

When you compare one period with another, you find it is not as simple as it was bad then, or it is worse now. Methods are different, but the intention is the same. Both old censors and new censors operate in the hope that they can bring more silence. In Soviet times there was a bureau that gave newspapers a stamp of approval. Now in Russia journalists report that self-censorship is one of the greatest threats to the free flow of ideas and information. Others say the public’s appetite for investigative journalism that challenges the authorities has disappeared. Meanwhile Vladimir Putin’s government has introduced bills banning “propaganda” of homosexuality and promoting “extremism” or “harm to children”, which can be applied far and wide to censor articles or art that the government doesn’t like. So far, so familiar.

Censorship and threats to freedom of expression still come in many forms as they did in 1972. Murder and physical violence, as with the killings of bloggers in Bangladesh, tries to frighten other writers, scholars, artists and thinkers into silence, or exile. Imprisonment (for example, the six year and three month sentence of democracy campaigner Rasul Jafarov in Azerbaijan) attempts to enforces silence too. Instilling fear by breaking into individuals’ computers and tracking their movement (as one African writer reports to Index) leaves a frightening signal that the government knows what you do and who you speak with.

Also in this issue, veteran journalist Andrew Graham-Yool looks back at Argentina’s dictatorship of four decades ago, he argues that vicious attacks on journalists’ reputations are becoming more widespread and he identifies numerous threats on the horizon, from corporate control of journalistic stories to the power of the president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, to identify journalists as enemies of the state.

Old censors and new censors have more in common than might divide them. Their intentions are the same, they just choose different weapons. Comparisons should make it clear, it remains ever vital to be vigilant for attacks on free expression, because they come from all angles.

Despite this, there is hope. In this issue of the magazine Jamie Bartlett writes of his optimism that when governments push their powers too far, the public pushes back hard, and gains ground once more. Another of our writers Jason DaPonte identifies innovators whose aim is to improve freedom of expression, bringing open-access software and encryption tools to the global public.

Don’t miss our excellent new creative writing, published for the first time in English, including Russian poetry, an extract of a Brazilian play, and a short story from Turkey.

As always the magazine brings you brilliant new writers and writing from around the world. Read on.

© Rachael Jolley

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.