1 Aug 2019 | Artistic Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”108364″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Nothing defined 20th-century American culture quite like the comic book. Comics in their popular, serialised form emerged in 1930s New York City, mass-produced by recent immigrants and their children who had grown up reading one-strip funny cartoons. The early success of Superman (the concoction of two young Jewish immigrants, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster) spurred the rapid growth of the comics industry. By the mid-1940s, many small-time comic publishers were churning out hundreds of series and characters of all genres.

Soon after comics’ meteoric rise in popularity, the industry drew criticism. Comics were never regarded as “high art” despite the aspirations of many who worked in the industry. They were unapologetically for children and adolescents, produced as entertainment for the lower classes. Many of the comics genres that rose to extreme popularity in the 1930s, 40s and 50s revolved around crime, ghosts and ghouls, aliens, and pulpy romance. Notably, EC Comics started by Bill Gaines was famous for Crime Does Not Pay, a comic that published macabre tales that blurred the line between good and evil. Gaines inherited the publishing business from his father, who had died suddenly in a boating accident, and EC comics became synonymous with the seediest corners of the comics industry.

Because of the gore and sexual content of early comics, the parents of devoted teenage comics readers began to worry about the effect of the comic book on children. The Catholic Church at the time allowed local dioceses to impose bans on certain books, which they quickly levied against most comic books, placing them on lists of books thought to be unsuitable for good Catholic youth. Concerned parents around the country wrote op-eds in local newspapers about the dangers of comics. Parent-teacher associations organised comic book burnings, though Nazi book burnings were still fresh in national memory. Students themselves occasionally spearheaded book burnings and comic purges from school libraries, encouraging friends to bring their collections to fuel the bonfire.

The final straw in the early 1950s was in the form of a book called Seduction of the Innocent, by psychologist Frederic Wertham. Wertham’s book contained no scientific research and was based solely on anecdotal interactions between the psychologist and patients at his clinic. It was unapologetically political and linked the rise of the comic book industry to rises in youth crime (which did not, statistically, exist). The central argument of his book was that the cartoon violence on the pages of comics spurred youth to commit more crimes and that banning comics would drastically decrease rates of youth criminality. Seduction of the Innocent spurred a series of Senate hearings on whether the government should take action against comics. Led by famous Senator Estes Kefauver, the hearings were televised for the comics-hating public to see. This was not the first time government action against comics had been considered: at that point, several bills had been introduced in different state legislatures to enact government censorship on the distribution of comics, though most had been shot down on First Amendment grounds.

The Senate hearings terrified the entire comics industry. Bill Gaines, high on stimulants, testified at the hearings. In a riveting cross-examination by Senator Kefauver, Gaines was backed into a corner, forced to defend a recent Crime Does Not Pay cover (which depicted a hand holding a severed woman’s head) as “good taste.” The Senate hearings led only to a harsh denouncement of comic books and endorsement of Wertham’s pseudoscientific theories about their link to youth crime. The government took no official action to censor comics, though it did encourage the industry to censor itself, which the industry gladly did.

Gaines had, years earlier, formed the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers (ACMP). In an effort to resist government censorship, Gaines rallied ACMP again, though fellow publishers thought it safer to develop intra-industry codes rather than to allow the government to officially censor comics. Fearful that government censorship was worse, the latent ACMP morphed into the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA). The CMAA then created the Comics Code Authority (CCA), which developed extremely strict guidelines for comics publishing–no weapons, good must always triumph over evil, women must be conservatively dressed. Since the CMAA controlled the means of production of comic books, without CCA approval no comics could go to the presses.

Full-time CCA censors would comb through every comic issue, circling any potential violations. The publishers who had previously specialised in crime comics, romances, science fiction and fantasy couldn’t get anything published — essentially, only superheroes remained. Comics became sanitised, and many smaller publishers closed down, with comics creators leaving the industry in droves. Bill Gaines’s EC Comics was finally shuttered when CCA censors objected to Gaines sympathetically portraying a black man in a comic.

The CCA’s regulations slowly loosened over time, yet the CCA remained essential in the industry for decades. Without the now-notorious CCA seal of approval on the cover, no comic would be sold. As independently publishing became easier and comics publishers consolidated, there became an independent financial motive for publishing and selling comics from many publishers regardless of their adherence to CCA standards. CCA standards also became looser, as artists infused already-popular series with themes that would have been previously unacceptable–for example, comic giant Jack Kirby famously included a storyline about drug addiction in a popular superhero series. In the 2000s, large publishers stopped seeking CCA approval, starting with Marvel Comics in 2001. By 2011, DC and Archie comics stopped seeking CCA approval for their comics, rendering the agency finally defunct.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Banned Books Week / 22-28 Sept 2019″ use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bannedbooksweek.org.uk%2F|||”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”103109″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.bannedbooksweek.org.uk/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Banned Books Week UK is a nationwide campaign for radical readers and rebellious readers of all ages celebrate the freedom to read. Between 22 – 28 September 2019, bookshops, libraries, schools, literary festivals and publishers will be hosting events and making noise about some of the most sordid, subversive, sensational and taboo-busting books around.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Jul 2019 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019

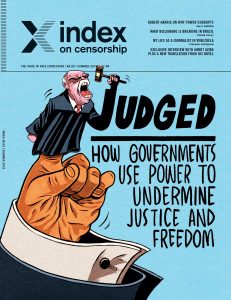

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index editor Rachael Jolley argues in the summer 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine that it is vital to defend the distance between a nation’s leaders and its judges and lawyers, but this gap being narrowed around the world” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

It all started with a conversation I had with a couple of journalists working in tough countries. We were talking about what kind of protection they still had, despite laws that could be used to crack down on their kind of journalism – journalism that is critical of governments.

It all started with a conversation I had with a couple of journalists working in tough countries. We were talking about what kind of protection they still had, despite laws that could be used to crack down on their kind of journalism – journalism that is critical of governments.

They said: “When the independence of the justice system is gone then that is it. It’s all over.”

And they felt that while there were still lawyers prepared to stand with them to defend cases, and judges who were not in the pay of – or bowed by – government pressure, there was still hope. Belief in the rule of law, and its wire-like strength, really mattered.

These are people who keep on writing tough stories that could get them in trouble with the people in power when all around them are telling them it might be safer if they were to shut up.

This sliver of optimism means a great deal to journalists, activists, opposition politicians and artists who work in countries where the climate is very strongly in favour of silence. It means they feel like someone else is still there for them.

I started talking to journalists, writers and activists in other places around the world, and I realised that although many of them hadn’t articulated this thought, when I mentioned it they said: “Yes, yes, that’s right. That makes a real difference to us.”

So why – and how – do we defend the system of legal independence and make more people aware of its value? It’s not something you hear being discussed in the local bar or café, after all.

Right now, we need to make a wider public argument about why we all need to stand up for the right to an independent justice system.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”On an ordinary day, most of us are not in court or fighting a legal action, so it is only when we do, or we know someone who is, that we might realise that something important has been eroded” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

We need to do it because it is at the heart of any free country, protecting our freedom to speak, think, debate, paint, draw and put on plays that produce unexpected and challenging thoughts. The wider public is not thinking “hey, yes, I worry that the courts are run down, and that criminal lawyers are in short supply”, or “If I took a case to trial and won my case I can no longer claim my lawyer’s fees back from the court”. On an ordinary day, most of us are not in court or fighting a legal action, so it is only when we are, or when we know someone who is, that we might realise that something important has been eroded.

Our rights are slowly, piece by piece, being undermined when our ability to access courts is severely limited, when judges feel too close to presidents or prime ministers, and when lawyers get locked up for taking a case that a national government would rather was not heard.

All those things are happening in parts of the world right now.

In China, hundreds of lawyers are in prison; in England and Wales since 2014 it has become more risky financially for most ordinary people to take a case to court as those who win a case no longer have their court fees paid automatically; and in Brazil the new president, Jair Bolsonaro, has just appointed a judge who was very much part of his election campaign to a newly invented super-ministerial role.

Helpfully, there are some factors that are deeply embedded in many countries’ legal histories and cultures that make it more difficult for authoritarian leaders to close the necessary space between the government and the justice system.

Many people who go into law, particularly human-rights law, do so with a vision of helping those who are fighting the system and have few powerful friends. Others hate being pressurised. And in many countries there are elements of the legal system that give sustenance to those who defend the independence of the judiciary as a vital principle.

Nelson Mandela’s lawyer, Sir Sydney Kentridge QC, has made the point that judges recruited from an independent bar would never entirely lose their independence, even when the system pressurised them to do so.

He pointed out that South African lawyers who had defended black men accused of murder in front of all-white juries during the apartheid period were not easily going to lose their commitment to stand up against the powerful.

Sir Sydney did, however, also argue that “in the absence of an entrenched bill of rights, the judiciary is a poor bulwark against a determined and immoderate government” in a lecture printed in Free Country, a book of his speeches.

So it turned out that this was the right time to think about a special report on this theme of the value of independent justice, because in lots of countries this independence is under bombardment.

It’s not that judges and lawyers haven’t always come under pressure. In his book The Rule of Law, Lord Bingham, a former lord chief justice of England and Wales, mentions a relevant historical example. When Earl Warren, the US chief justice, was sitting on the now famous Brown v Board of Education case in 1954, he was invited to dinner with President Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower sat next to him at dinner and the lawyer for the segregationists sat on his other side. According to Warren, the president went to great lengths to promote the case for the segregationists, and to say what a great man their lawyer was. Despite this, Warren went on to give the important judgement in favour of Brown that meant that racial segregation in public schools became illegal.

Those in power have always tried to influence judges to lean the way they would prefer, but they should not have weapons to punish those who don’t do so.

In China, hundreds of lawyers who stood up to defend human-rights cases have been charged with the crime of “subverting state power” and imprisoned. When the wife of one of the lawyers calls on others to support her husband, her cries go largely unheard because people are worried about the consequences.

This, as Karoline Kan writes on p23, is a country where the Chinese Communist Party has control of the executive, judicial and legislative branches of government, and where calls for political reform, or separation of powers, can be seen as threats to stability.

As we go to press we are close to the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square killings, when thousands of protesters all over China, from all kinds of backgrounds, had felt passionately that their country was ready for change – for democracy, transparency and separation of powers.

Unfortunately, that tide was turned back by China’s government in 1989, and today we are, once more, seeing China’s government tightening restrictions even further against those who dare to criticise them.

Last year, the Hungarian parliament passed a law allowing the creation of administrative courts to take cases involving taxation and election out of the main legal system (see p34). Critics saw this as eroding the gap between the executive and the justice system. But then, at the end of May 2019, there was a U-turn, and it was announced that the courts were no longer going ahead. It is believed that Fidesz, the governing party in Hungary, was under pressure from its grouping in the European Parliament, the European People’s Party.

If it were kicked out of the EPP, Hungary would have in all likelihood lost significant funding, and it is believed there was also pressure from the European Parliament to protect the rule of law in its member states.

But while this was seen as a victory by some, others warned things could always reverse quickly.

Overall the world is fortunate to have many lawyers who feel strongly about freedom of expression, and the independence of any justice system.

Barrister Jonathan Price, of Doughty Street Chambers, in London, is part of the team advising the family of murdered journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia over a case against the Maltese government for its failure to hold an independent inquiry into her death.

He explained why the work of his colleagues was particularly important, saying: “The law can be complex and expensive, and unfortunately the laws of defamation, privacy and data protection have become so complex that they are more or less inoperable in the hands of the untrained.”

Specialist lawyers who were willing to take on cases had become a necessary part of the rule of law, he said – a view shared by human-rights barrister David Mitchell, of Ely Place Chambers, in London.

“The rule of law levels the playing field between the powerful and [the] powerless,” he said. “It’s important that lawyers work to preserve this level.”

Finally, another thought from Sir Sydney that is pertinent to how the journalists I mentioned at the beginning of this article keep going against the odds: “It is not necessary to hope in order to work, and it is not necessary to succeed in order to hope in order to work, and it is not necessary to succeed in order to persevere.”

But, of course, it helps if you can do all three.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on local news

Index on Censorship’s spring 2019 issue is entitled Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

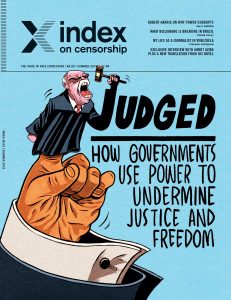

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”How governments use power to undermine justice and freedom” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F06%2Fmagazine-judged-how-governments-use-power-to-undermine-justice-and-freedom%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at the narrowing gap between a nation’s leader and its judges and lawyers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”107686″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/06/magazine-judged-how-governments-use-power-to-undermine-justice-and-freedom/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Jun 2019 | China, News and features, United Kingdom, United States, Venezuela, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019 Extras

In the Index on Censorship summer 2019 podcast, we focus on how governments use power to undermine justice and freedom. Lewis Jennings and Rachael Jolley discuss the latest issue of the magazine, revealing their top picks and debating what rating they would be under China’s social credit rating system. Guests include best-selling Chinese author Xinran, who delves into surveillance in China; Italian journalist Stefano Pozzebon, who reveals the dangers of being a foreign journalist in Venezuela; and Steve Levitsky, the co-author of The New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die, discusses political polarisation in the US.

Print copies of the magazine are available on Amazon, or you can take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpetine Gallery and MagCulture (all London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool). Red Lion Books (Colchester) and Home (Manchester). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

The Summer 2019 podcast can also be found on iTunes.

21 May 2019 | Artistic Freedom, News and features, Press Releases, Risks, Rights and Reputations

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]UK-based freedom of expression organisation Index on Censorship has launched a new service to support arts organisations facing censorship. Building on a successful program of workshops for senior managers and boards in 2018, Index is setting up the Arts Censorship Support Service as part of its Artistic Freedom programme.

The Arts Censorship Support Service will provide assistance to colleagues in the cultural sector facing issues of censorship. The service is open to anyone in the cultural sector, employed or self-employed and the initial consultation will be free of charge. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times” color=”custom” background_style=”rounded” background_color=”black” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

The Arts Censorship Support Service is part of a broader programme of work offering resources to the arts sector in the UK.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship staff as well as a network of senior-level cultural sector and legal professionals with significant experience in managing complex ethical, reputational and legal issues, are available to offer advice on a wide range of issues, including:

- Checking at the earliest stage of production of a new work whether there is the potential of a legal challenge

- Advising on a communications strategy in support of provocative work

- Advising how to manage hostile media attention

- Providing moral support and guidance on how to deal with the emotional stress associated with controversy.

The Arts Censorship Support Service is part of a broader programme of work offering resources to the arts sector in the UK. Index also offers bespoke training and consultancy at all levels, from one-to-one consultancy to boards and staff training, from schools workshops to development of bespoke guidance on freedom of expression.

A resource centre on the Index website also provides information via case studies that examine examples of how arts organisations have handled highly sensitised, contentious and complex issues in today’s society. Collectively, the case studies aim to equip arts organisations and artists with insight into what worked and what didn’t, what was contested, and what lessons were learned.

Five booklets covering Art and the Law give clear information about criminal laws governing freedom of expression and the protections available to arts organisation in mounting challenging work.

For more information, please contact: Sean Gallagher, Index on Censorship, [email protected][/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1558424600419-80bbdd93-e9cd-4″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

It all started with a conversation I had with a couple of journalists working in tough countries. We were talking about what kind of protection they still had, despite laws that could be used to crack down on their kind of journalism

It all started with a conversation I had with a couple of journalists working in tough countries. We were talking about what kind of protection they still had, despite laws that could be used to crack down on their kind of journalism