The age of unreason

FEATURING

Ian Rankin

Author

Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe

Poet

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Writer and professor

FEATURING

Author

Poet

Writer and professor

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

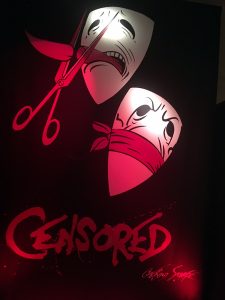

Censored by George Scarfe

Marking the 50th anniversary of the end of 300 years of theatre censorship, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition explores how restrictions on expression have changed.

The Theatres Act 1968 swept away the office of the Lord Chamberlain, which had the final say on what could appear on British stages.

“The 1968 Theatres Act was one of several landmark pieces of legislation in the 1960s, including the end of capital punishment, the legalisation of abortion, the introduction of pill, and the decriminalisation of homosexuality (for consenting males over the age of 21),” Harriet Reed, assistant curator at the V&A said.

Plays that had the potential to create immoral or anti-government feelings were banned by the Lord Chamberlain’s office or ordered to be edited. The exhibition includes original manuscripts with notes on what needs to be changed and letters from Lord Chamberlain explaining why the edits are required.

In the exhibition there are several pieces including a manuscript about the play Saved by Edward Bond. The play tells the story of a group of young people living in poverty and includes a scene in which a baby is stoned to death.

“When the Royal Court Theatre submitted the play to the censor, over 50 amendments were requested. Bond refused to cut two key scenes, stating ‘it was either the censor or me – and it was going to be the censor’. As a result, the play was banned,” Reed said.

Before the act was passed, playwrights got around the law by staging banned plays in “members clubs” which meant they could not be persecuted since it was private venue.

“The continued success of this strategy and the reluctance to prosecute made a mockery of the Lord Chamberlain’s powers and reflected the increasingly relaxed attitudes of the public towards ‘shocking’ material.

“The first night after the Act was introduced, the rock musical Hair opened on Shaftesbury Avenue in the West End. It featured drugs, anti-war messages and brief nudity, ushering in a new age of British theatre,” Reed said.

The exhibition changes from showcasing plays that were censored by the state to art, plays, movies, and music that are censored by society as a whole.

“It could be argued that a mixture of government intervention, funding/subsidy withdrawals, local authority and police intervention, self-censorship, and public protest now regulates what is seen on our stages,” she said.

Behzti, a play, and Exhibit B, a performance piece, were cancelled after protests by the public. The creators of both pieces were advised by the police to cancel their plays for health and safety reasons related to protests over the content.

Similarly, Homegrown, a play about radicalisation created by Muslims was shut down by the National Youth Theatre. The play was later published and a public reading was held.

On video, people involved in the UK arts industry such as Lyn Gardner, a theatre critic and Ian Christie, a film historian comment on what they believe to be censorship today. They cite art institutions that refuse to exhibit controversial material for fear of losing funding or facing public uproar. Julia Farrington, associate arts producer at Index on Censorship and one of the participants, calls this the “censorship of omission.”

The exhibition is capped by a piece by George Scarfe. The piece, the last work that attendees see, is a painting of two white masks on black cloth. The first one which is slightly higher and to the right of the second has it red tongue sticking out with the tip severed by a red scissors. The second one has a red cloth tied around it mouth. The word Censored is written in red and all caps below the two masks.

The painting is bold and the image of the tongue being cut off by scissors creates a “visceral” feeling. It depicts the two types of censorship that people now face– either talk and be violently censored or self-censor and never be heard.

“Many people would say that we are freer to express ourselves than ever before – with the boom of social media, we are able to communicate our thoughts and opinions on an unprecedented scale. This can also, however, invite more stringent and aggressive censorship from either the platform provider or under fear of criticism from other users,” Reed said.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534246236330-00e1ebeb-95f3-4″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_media_grid grid_id=”vc_gid:1533806465014-9fa23910-6976-8″ include=”101950,101948,101949,101952,101947,101951″][vc_column_text]To an outsider, the most startling part of artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara’s arrest on 21 July for attempting to protest on the Capitol steps in Havana was the passivity, bordering on fearful ignorance, of his fellow Cubans at the scene. When he shouted and resisted, there was no response. When officers forced his head back to get him into the car, no one batted an eye.

Such is a reality Otero Alcántara and Yanelyz Nuñez, founders of the 2018 Index award-winning Museum of Dissidence, and the independent art community are working to change for the millions of Cubans whose freedom of expression remains severely constrained in the post-Castro era. Describing the challenges modern Cuba faces, Alcántara and Nuñez said “there are two political extremes that fail to dialogue and, in the background, that people are confused, apathetic, saturated with politics, and repressed by fear.”

As Index fellowships and advocacy officer Perla Hinojosa says, “When your freedoms are limited for so long, it becomes natural that when you try to express yourself in a different manner, you are stopped by authorities, so I’m assuming that the Cuban people are desensitised.”

By covering themselves in excrement and demanding “free art,” the artists planned to emphasise that “independent artists are shit for the Cuban state” as Otero Alcántara said after two days’ imprisonment and beatings. He added that they are portrayed as dissidents and lack a platform to engage with the public, much less the government, on legislation like Decree 349, a harsh new law allowing the government to sanction what art can be displayed or exchanged in private settings. Otero Alcántara believes it is “a very clear response” to the Museum of Dissidence’s independent art biennial, held in May despite government attempts to derail it.

While only Nuñez could carry out the protest and demand a meeting with the minister of culture regarding Decree 349, in its aftermath, the artists catalysed a movement of peaceful resistance, digital campaigning and public dialogue to draw national attention to the law and culture of artistic censorship in Cuba. Nuñez, Otero Alcántara and Amaury Pacheco and Iris Ruiz, who were also arrested, have taken the protest to social media, using the hashtags #NOALDECRETOLEY349 (#NOTODECREELAW349) and #artelibre (#freeart) on their Facebook page representing Cuba’s independent artists.

Pacheco is assembling a gallery of Cuban and international artists endorsing the campaign’s phrase: “together we can… no to Decree 349, the law that converts art into a crime.” Featured visual and performing artists like Damián Valdéz Dilla and René Rodríguez tell Cubans that “you are stronger than you think” and “don’t count the days… make sure your days count.” Such messages serve to invigorate a nation with a culture deeply rooted in the suppression of unsanctioned ideas. In his profile, Otero Alcántara encourages the public to “dream when reality tires us, to return to reality when dreaming tires us.”

Hinojosa believes “that this work embodies what meaningful activism against censorship looks like. You can be arrested and threatened but you know you have rights and are willing to stand up for them. They are creating dialogue around the issue for the betterment of themselves and their communities.”

Apart from digital activism, the artists are hosting a public debate in the first week of August. The participating independent artists and journalists have raised concerns that Decree 349 offers a “large margin of action for Cuban censors.” Their objective is to include artists from Cuba and the international community in the conversation and propose a cultural policy that is more considerate of artistic expression. Alcántara and Nuñez believe that “We belong to a generation that wants urgent improvements. A generation that, although it has no political culture, knows what it wants.”

Hinojosa says “Index aims to amplify fellows’ work so that it doesn’t go unseen and provide international support for their activism. This is essential to pressure the government and create dialogue with the community, to tell the Cuban people that it is important to speak out.”

Do you agree with the Museum of Dissidence that artists in Cuba should not be criminalised for their work? If so, please sign their petition against Decree 349.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/-6JnYDCLKIE”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Through the fellowships, Index seeks to maximise the impact and sustainability of voices at the forefront of pushing back censorship worldwide.

Learn more about the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1533806465027-3ff50ed2-b280-7″ taxonomies=”7874, 23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

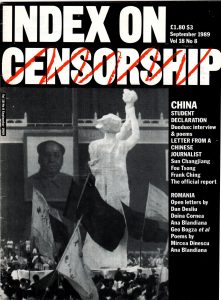

China: student declaration, the September 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine here

Index has covered censorship in China since 1973. While the government’s approach has evolved in today’s digital era, in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, key themes surrounding the suppression of political dissent and free expression remain as pressing as ever. Explore them in this reading list featuring prominent Chinese academics, activists and writers.

May 2009 vol. 38 no. 2

Wang Dan, a leading figure in the 1989 protests, talks to the writer Xinran about the fallout and the legacy of Tiananmen. Wang Dan was released from prison in 1998 and exiled to the United States. He completed his PhD at Harvard University. He is chairman of the Chinese Constitutional Reform Association and on the advisory board of Wikileaks. Xinran worked as a journalist and radio presenter in China. She now lives in London. Her books include The Good Women of China (Vintage), Sky Burial (Vintage) and China Witness (Chatto & Windus).

Read the full article here.

June 1989 vol. 18 no. 8

Student leaders Liu Xiaobo, Zhou Duo, Hou Dejian and Gao Xin declared a hunger strike in Tiananmen Square just before the massacre on the night of 3-4 June 1989. This translation of excerpts of the declaration was first published in The Independent, 10 June 1989.

Read the full article here.

From Coming back to life: written for the ‘Tiananmen mother’

December 2010 vol. 39 no. 4

This poem was written by Chinese poet Shi Tao who has faced censorship, government threats and imprisonment for his work. It was translated by English scholar Frances Wood.

Read the full article here.

April 2018 vol. 47 no. 1

China has passed a law to make telling the wrong sort of history punishable. Louisa Lim, author of a book on the Tiananmen Square massacre, says she wouldn’t be able to research her book today.

Read the full article here.

September 1999 vol. 28 no. 5

In 1999, the 10th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre passed quietly enough but as British journalist John Gittings writes, the desire for change and for democracy in China is as strong as ever.

Read the full article here.

September 1989 vol. 18 no. 8

One of China’s leading young poets Li Shizheng, known as DuoDuo, was in Tiananmen Square on the day of the massacre. He flew to Britain the day afterwards, where he was interviewed by Gregory Lee for Index.

Read the full article here.

Subscribe to the print edition Index on Censorship magazine here for £35 or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year, with a free trial).