Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

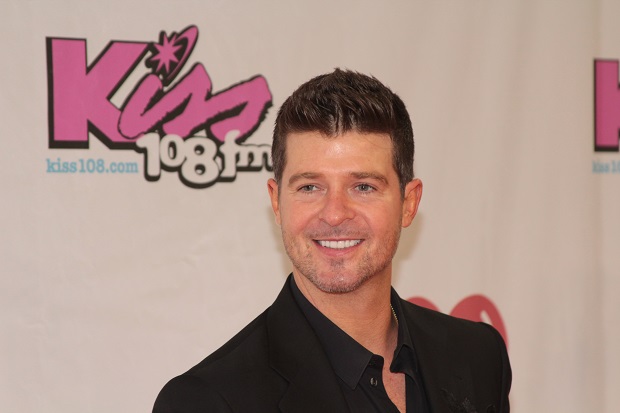

Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines song has been banned in at least 20 student unions after it was released in March 2013. (Image: George Weinstein/Demotix)

I consider myself to be privileged to have the job that I have-I am a university lecturer who teaches Popular Music Culture to undergraduates and post-graduates. This is a subject that is popular among students because the majority of them like music and have an opinion on it. What I love most about my job is the range of interesting conversations my students and I have around popular music and its impact on culture, politics and society.

Music is ubiquitous and it touches people of all cultures, classes and creeds in a multitude of ways. What comes out of the discussions I have highlights both the joy and the anger it can evoke. Some of those discussions can bring forward some sensitive, awkward and challenging opinions and issues but what they do succeed in doing is highlighting issues that we as adults can explore, discuss, argue, rationalise and at time agree to differ on-but in a mature and accepting way, appreciating that we are all different.

So during my lecture on popular music and gender back in November 2013 I opened up a discussion around Robin Thicke’s summer release “Blurred Lines”. I feel no real need to go into any great detail about the fastest selling digital song in history and biggest single hit of 2013. Why? Because the controversy surrounding this song, such as misogynistic positioning with “rapey” lyrics that excuse rape and promote non-consensual sex and, among many other accusations, the promotion of “lad culture”, is abundant on the internet.

My students’ views on this song, and accompanying video mixed with both females and males defending the song and Thicke’s counter argument of it – promoting feminism, it being tongue in cheek and a disposable pop song – to those who, again both male and female, just wanted to castrate him for putting women’s rights and equality back into the dark ages.

Now the scene in the lecture theatre had been set I wanted to garner from them views on what I considered to be equally, if not more important – the issue that over 20 university student unions in the UK had banned the song from being played in their student union bars and union promoted events. This includes the prevention of in-house and visiting DJs playing it on student union premises and ,in some cases, the song not being aired on student union radio and TV stations’ playlists. In their defence the majority of these universities decided to ban after complaints from some of their students, but I am yet to determine whether all these universities reached this decision after an open and democratic process of consensus through voting or otherwise.

What I did find interesting among the many statements from presidents and vice-presidents of the student unions was one given to the New Musical Express, in November 2013, by Kirsty Haigh, the vice president of Edinburgh University Student Association.

The decision to ban ‘Blurred Lines’ from our venues has been taken as it promotes an unhealthy attitude towards sex and consent. EUSA has a policy on zero tolerance towards sexual harassment, a policy to end lad culture on campus and a safe space policy-all of which this song violates”.

However what Haigh does not go on to explain is exactly how this song does that. I am also intrigued by the comment about a policy to end ”lad culture” as Haigh does not allude to a clearly defined set of parameters specifying what counts as ”lad culture/banter”. One might ask if identifying a specific gender (lad) is this not targeting and discriminating against that gender?

I am struggling to find what constitutes ”lad culture” as opinions differ, however the National Union of Students’ That’s What She Said report published in March 2013 defines it as: “a group or ‘pack’ mentality residing in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption and ‘banter’ which was often sexist, misogynistic, or homophobic”. But does lad culture equate to sexual harassment-is there a connection or is this creating guilt by association? Some critics claim that ”lad culture” was a postmodern transformation of masculinity, an ironic response to ”girl power” that had developed during the noughties.

Allie Renison’s article Blurred lines: Why can’t women dance provocatively and still be empowered?, published in The Telegraph in July 2013, states that “Teenage girls and grown women spend countless hours confiding in each other about the finer details of physical intimacy, and I can safely say that even without a sex-obsessed pop culture this would still be the case.”

This has to some degree been confirmed by one of my students who is a member of the university girls’ hockey team and girls’ football team. She says that they go out as a group, taking part in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption and banter which is often sexist and misandry and involves intimate commentary on the male anatomy and men’s sexual prowess.

So would that then constitute “ladette” culture or “girl power” culture? Do EUSA have a policy to end ladette culture on their campus?

But this isn’t really the core issue here; the issue is around censorship on campus, what constitutes a fair and balanced approach to these issues and where you draw the lines. Thirty years ago student unions were complaining about, and rallying against, censorship-now they are the ones doing the censoring. So where does this leave the issue of censorship?

Starting with music, has Blurred Lines been singled out or do those twenty university student unions have a clear policy on banning songs that might include Prodigy’s Smack My Bitch Up, Jimi Hendrix’s Hey Joe (condoning the shooting of women who cheat on their men), Robert Palmer’s Addicted To Love (the lyrics could be seen to suggest date rape), Rolling Stones’ Under My Thumb, or Britney Spear’s Hit Me Baby One More Time? The list could go on and on, including songs that incite violence, racism or revolution. Do student unions around the country have concise and definitive lists of songs that should be banned or censored or is it a matter for a small group of elected people? And when you leave a group of people to act as moral arbiters then how do you control their decision making power?

Did we not collectively settle this matter in the 90s? Didn’t we conclude that outrage over pop music is a music marketer’s dream and inevitably increases sales for the artist? Aren’t popular music lyrics supposed to be challenging, full of danger and ambiguity? And do we only stop at popular music?

It could be argued that Mozart’s Don Giovanni revels in the actions of a rapist as does Britten’s Rape of Lucretia, and what of literature, do we ban Nabokov’s Lolita, Oscar Wilde’s Salome? Shouldn’t student unions be picketing concert halls, storming the libraries and art collections of universities and start demanding the removal of offensive material or at worst the burning of books and paintings in homage to a misguided Ray Bradbury envisioned cultural pogrom? If you are going to start banning or censoring cultural artefacts then please at least have some sort of consistency otherwise you leave yourself open to criticism.

So is this censorship? I would argue it is. If policy prevents a visiting DJ from playing a particular song at a student union bar, because some people do not approve of it, then that is censorship. I myself do not disagree with the criticism of the lyrical content of Blurred Lines, or condone them, though one could argue about their potential polysemic interpretation. What this highlights is perhaps an inconsistency in the processes of censorship by the student union.

Working in a university, I strongly believe that one of the core purposes of the academy is to create a space to allow young adults, on their journey of personal development, to explore their own opinions and prejudices, while considering those of others. A space where they can hear a multitude of views and draw their own conclusions from them; engage in constructive debate, work these issues through. Universities, of all places, should foster a culture of free speech and free expression wherever reasonably expected. Yes, there are always going to be challenges to what is appropriate and acceptable, whatever those challenges are the banning or censoring of material always has to be done within the law. That is how we develop as individuals and a society.

This article was published on February 26, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Turkey stands at 154 out of 180 places on Reporters Without Borders 2014 Press Freedom Index.

As of December 2013, a total of 211 journalists were behind bars somewhere in the world. Almost one fifth of these alone were jailed in Turkey, making it the country with the most number of journalists imprisoned globally, and placing it behind countries with such as Iran and China.

In the past 18 months many renowned journalists have been removed from their positions due to direct and increasing government pressure on media organisations in an attempt to control the level of critical coverage.

The height of government pressure came during the June 2013 Gezi Park protests, in which 153 journalists were injured and 39 detained for just doing their job.

The majority of mainstream national TV channels failed to cover the initial protests for fear of backlash from the government. The recent approval of a new “internet law”, a law brought in on the grounds of protecting the privacy of private information, is seen by many as the latest step in a conscious effort by the government to control freedom of expression in Turkey.

In a 2007 article, Concentration of ownership, the fall of unions and government legislation in Turkey (£) journalism professor Christen Christensen argued that the enormous power of Turkish media owners leaves journalists powerless.

Journalists’ Trade unions are seen as “useless” in, leaving reporters vulnerable to economic and political pressure. In the same article, Christensen more importantly stated that while there has been an increase in penalties for crimes committed through print or mass media, simultaneously there is a lack of provisions securing the rights of journalists to report and discuss issues. The difficulty of carrying out the profession in Turkey is enhanced by the restrictions on access and disclosure of information and the vague language used to define defamation and insult.

Today, a high number of journalists have been charged under Turkey’s anti-terrorism legislation The law’s vague wording allows a broad interpretation what constitutes support for a terrorist organisation. Many high profile journalists, such as Nedim Şener, Ahmet Şık and Cumhuriyet’s Mustafa Balbay, were charged with involvement in the “Ergenekon plot” – an alleged shadowy conspiracy that authorities claim aimed to overthrow the government. These charges have been laced with claims of falsified evidence, discrepancies in computer records and doctoring of evidence.

The grounds for arrests have similarly been a cause for confusion, Şık, for example, was arrested for allegedly supporting Ergenekon when his unpublished book was allegedly found on internet news portal OdaTV computers, while evidence against Mustafa Balbay comprised of documents seized from his home and office, which he states were notes and recorded conversations with government and military officials conducted for the purpose of his journalism.

Again, the same anti-terrorist legislation has resulted in the arrest of several Kurdish journalists for what authorities say is dissemination of propaganda aligned with the banned Kurdish Worker’s Party, or PKK, and related organisations.

As political tensions in the country increase, vague legal frameworks continue to be the enemy of not only journalists, but also other groups, most significantly students – all of whom are being taught to fear the implications of expressing their thoughts. Despite there being talks on revising the anti-terrorism legislation to narrow its scope, it is clear that the major link between the above arrests is the presence of a voice of opposition and the lack of a strong legal framework to ensure a sound judicial process.

Today, journalists such as Nedim Şener, Ahmet Şık and Mustafa Balbay, still face jail time if sentenced and it is only with a revision of the law in question and the wider legal framework relating to journalists that the profession will be able to develop and fulfil its democratic role.

This article was published on 25 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

The Indian judiciary, with its prickly ego and halo of righteousness, has always wielded the sword of “contempt” in a swashbuckling manner.

The Indian judiciary, with its prickly ego and halo of righteousness, has always wielded the sword of “contempt” in a swashbuckling manner.

In 1995, the movie Gentleman had some scenes in which judges were shown as being subservient to politicians, and susceptible to bribery. The filmmaker had two options- delete those “offending” scenes, or face prison for contempt of court. Needless to say, he settled for the former. Then in 2001, a fortnightly magazine carried out a performance evaluation of some judges of the Delhi High Court, and published a Report Card, grading them on integrity and competence. The court saw red at this “scandalising”, and slammed a sentence for conviction. Of course, the court praised itself: the judiciary was the “messiah” which protected the press and media from state interference. Meanwhile, when it comes to allegations of personal misdemeanour and malfeasance by judges, nobody needs to even petition the court. It swoops down on its own and muzzles the press.

However, this imperiousness pales in comparison to the Delhi High Court’s award of a gag order in the case of Justice Swatanter Kumar, a retired judge of the Supreme Court, accused of sexually harassing one of his female interns. The 16 January order is nothing less than a generous reward to a SLAPP suit, and worse, it also reveals a manifest bias in favour of the plaintiff, almost as if there was a concerted effort to stifle accountability.

On 30 November 2013, a former intern filed a complaint of sexual harassment against the judge, and when the Supreme Court declined to intervene, on 10 January, she took recourse to a PIL (Public Interest Litigation) before the same court. Coming right on the heels of another similar case, it made to all the front pages and television channels. Though there were some headlines which could have been phrased better, not a single paper or channel even remotely speculated on the veracity of the allegations. All they did was quote from the complainant’s petition and disclose the name of the judge. On 14 January, a phalanx of legal eagles threw their lot in with the accused judge and made a beeline for the Delhi High Court. Their vociferous assertion was tha newspapers, television channels, and the intern had colluded to tarnish the reputation of an upright judge by leveling malicious and scurrilous charges.

Two questions hit us at this juncture. One: when the petition was pending before the Supreme Court, why would the plaintiffs rush to the Delhi High Court, unless of course, forum shopping was their objective ? Two: if their beef was with the allegedly defamatory reportage, why would they also sue the intern?

Parsing the order granting an interim injunction might hint at some answers. The issue before the court was a simple one – whether the defendant newspaper and television channels’ actions amounted to trial by media and resulted in adverse publicity against the accused judge. (Un)surpringly, Justice Manmohan Singh starts by praising the judge’s sterling record on the Bench, and arrogates to itself the right to decide whether there was a smidgen of truth in the allegations. He also holds forth on the need for a statute of limitations in cases of sexual harassment. Then he cites a Supreme Court judgement which had justified prior restraint on reportage and in one fell swoop imposes a blanket ban on reporting of the case. This ban’s scope is scary- besides media houses, “any other person, entity, in print or electronic media or via internet or otherwise” were also drawn in.

Effectively, it means that no one, not even a person or a blogger not connected with the case, could write, or even tweet anything about it. When in most jurisdictions bloggers are being granted the same protection as journalists, could there be a more regressive step?

Legally India, a web portal had used a heavily pixelated image of the judge, so as to eliminate any identifying marks and carried a report totally in accordance with the court’s injunction. Despite that, the fire-and-brimstone emails it received from the plaintiff’s solicitors leave no room for doubt- that intimidating into silence is the only objective. The plaintive plea about irreparable damage to reputation is only a chimera.

A free press is indispensable for speaking truth to power, even the vast powers of the judiciary. Moreover, the Constitution of India makes it incumbent upon the judiciary to protect the press so that accountability and rule of law do not remain mere shibboleths. And when this same august institution clearly appears to champions SLAPP suits, it is indeed a mockery of the rule of law, as a livid Editors Guild said without pulling any punches.

This article was published on 13 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Limitations and challenges to freedom of expression and of assembly in Turkey have – once again – come to international attention over the past year. But despite this, censorship of the arts is often under-reported.

Siyah Bant was founded in 2011 as a research platform that documents censorship in the arts across Turkey by a group of arts managers, arts writers and academics working on freedom of expression. The group is concerned that many instances of censorship in the art world, especially in the visual and performing arts, were under-reported and only circulated as anecdotes. Siyah Bant also found the blanket understanding that “it is the state that censors” to be insufficient.

The Gezi Park protests that began in late May 2013 not only highlighted the continued existence of police violence and the institutionalized use of excessive force that has long been a familiar sight in the Kurdish region, and, more recently, in the protests against hydroelectric plants in the Black Sea parts of Turkey. The demonstrations also made apparent the tight grip that the alliance of political establishment and business conglomerates have over Turkish print and broadcasting media, as numerous journalists were fired for reporting on the anti-government protests.

Together with China and Iran, Turkey has been taken the lead in terms of numbers of imprisoned journalists, many of which are charged under anti-terrorism laws. Currently, all eyes are on the amendments to internet law 5651 that passed parliament in early February 2014, now waiting to be signed into effect by President Abdullah Gül.

While the government claims these changes are to ensure privacy and clamp down on pornography, activists maintain that the law will procedurally ease the profiling of internet users and effectively heighten government control over online content. Turkey has already a questionable track record when it comes to internet freedom with access to more than 40,000 internet sites being restricted.

Rather than operating through bans and efforts at complete suppression that marked the 1980 coup d’état and its aftermath, the current censorship mechanisms in Turkey aim to delegitimize and discourage artistic expressions and their circulation.

Siyah Bant’s initial aim was two-fold: Firstly, the group conducted research in five cities to identify and examine different modalities of censorship and the actors involved in censoring motions. Secondly, Siyah Bant wanted to create awareness around censorship in the arts and facilitate solidarity networks in the advocacy for freedom of expression in the arts.

In the course of its research it set up a website that documents arts censorship in Turkey and assembled two publications. The first presents selected case studies of censorship in the arts in Turkey as well as international initiatives in the fight for freedom of expression. The second focuses more closely on artists’ rights and the legal framework of freedom of the arts in Turkey as well as the ways in which these laws are applied–or not applied, in most cases.

The reports below center on new developments in Turkish cultural policy and their effects on freedom of arts as well as interviews conducted in Diyabakir and Batman where artists engaged in the Kurdish rights struggle have long been subjected to differential treatment by the Turkish authorities. Research for these reports was supported by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

• Developments in cultural policy and its effects on freedom of the arts, Ankara

• Artists engaged in Kurdish rights struggle face limits on free expression

This article was published on 13 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org