18 Jun 2013 | Middle East and North Africa

August will mark the end of our time with Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran’s president since 2005. His successor, moderate cleric Hassan Rohani, was announced as the winner of this year’s election over the weekend.

Ahmadinejad, the Islamic Republic’s sixth president, brought along with him an aggressive foreign policy and a penchant for controversial statements — from

Ahmadinejad, the Islamic Republic’s sixth president, brought along with him an aggressive foreign policy and a penchant for controversial statements — from

questioning the Holocaust, to denying the existence of homosexuality in Iran, to claiming that the United States developed HIV to profit from African nations.

His time in office has been marked with many arbitrary arrests and restrictions on freedom of expression. During his first term, 14 publications were shut down, including newspaper Sharvand Emrooz (Today’s Citizen), closed for using an image of the then newly-elected US President Barack Obama on its front cover.

His re-election in 2009 sparked popular protests that became known as the “Green movement”, as demonstrators alleging that the result was fraudulent filled the streets. They were met with a brutal crackdown.

The aftermath of the election brought a rise in attacks on journalists and press freedom, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). As of December 2012, the organisation reported 45 journalists in prison.

Iran has also gained a reputation for online censorship, named one of the “enemies of the internet” by Reporters Without Borders (RSF). In 2010, the country created a “Cyber Army” to police the web. Following the disputed 2009 election, Facebook was banned in Iran in the name of curbing social unrest. Also in 2009, the country formed the “Organised Crime Surveillance Centre”, which according to RSF, has been used to pursue netizens.

Ahmadinejad also leaves behind a legacy of cultural censorship. According to a 2011 report published by information activists Small Media, Iran’s government “has become increasingly draconian in the imposition of restrictions and the implementation of new policies concerning the publication of books” following 2009’s election. Small media contend “there has been no other comparable era of such heavy-handed suppression since the instigation of the Islamic Republic in 1979.”

At the 2010 Tehran Book Fair, books approved published before 2007 were banned from being sold. Raha Zahedpour wrote for Index about this year’s fair:

“No one in the industry can anticipate what will and will not be allowed by Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Completed projects wait for months to be reviewed by state censors and most are returned with a long list of “required modifications.”

Iran’s system of censorship, combined with international sanctions have “put the publishing industry under intense pressure” according to Zahedpour.

The country’s film industry has also been crippled by its censors: independent as well as pro-reform filmmakers face punishment or jail time, while films with a regime slant receive financial backing. Filmmaker Jafar Panahi, for example, received a six-year jail sentence for “colluding in the gathering and making of propaganda against the regime” in 2010, as well as a ban preventing him from making films or traveling abroad for 20 years.

It’s not known what the outgoing leader’s next steps will be: he could stand trial in November, following unspecified complaints brought against him by Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani, a conservative rival. But some believe that the 56-year-old will not leave the political arena easily.

Sara Yasin is an Editorial Assistant at Index. She tweets from @missyasin

14 Jun 2013 | Comment, Europe and Central Asia, News

Russia’s new blasphemy law is censorship under the guise of protection for believers, says Padraig Reidy

In his speech on Russia’s Constitution Day in December 2012, Vladimir Putin bemoaned the decline of spiritual values.

“Today, Russia suffers an apparent deficit of spiritual values,” said Putin, as his Orthodox ally Patriarch Kirill nodded along.

The former KGB man continued: “We must wholeheartedly support the institutions that are the carriers of traditional values.”

So far, so Mother Russia.

What was interesting was that the president went on to say that it would be “amoral” to create laws governing spirituality. Putin commented ““Any attempts of the government to intervene with people’s beliefs are effectively a sign of totalitarian rule. It’s absolutely out of the question. It’s not our way.”

This would seem at odds with this week’s passing of a new blasphemy law, which will impose prison sentences and fines on people convicted of “public actions expressing clear disrespect for society and committed with the goal of offending religious feelings of the faithful”.

But it is in fact very much in the mould of the current trend for religious defamation law.

Traditionally, blasphemy was the crime of causing offence to God himself; now it is recast as causing offence to believers. Blasphemy laws are here to protect us. Look back at the testimony durings Pussy Riot’s trial, and again and again you hear the stories of poor innocent believers who were shocked by the women’s behaviour; even if the Patriarch and the president had wished to forgive the punk group, they had to think of the poor pious babushkas who had been rocked to the very core by an act that some admitted to not actually having witnessed.

Shamefully, Ireland has led the way in this trend. The Irish Defamation Act of 2009 established definitions and punishments for blasphemy where none had previously existed (in spite of the fact that the 1937 constitution recognised blasphemy as a crime, it did not define what blasphemy was, and thus, there had never been a conviction for blasphemy, or even a full trial, in the country).

The Irish law defines religious defamation as any action likely to cause “outrage among a substantial number of the adherents of [a] religion”, with fines of up to e25,000 payable by those found guilty.

The wording of the Irish bill was used as a template in the Organisation of Islamic Conference’s attempts to get the UN to recognise religious defamation as a crime.

Of course, the old-fashioned definitions of blasphemy still exist: in Egypt this week, writer Amer Saber was given a five-year sentence for “contempt of religion” for authoring a short story collection called “Where is God?”. And in Syria, a teenager was reportedly shot in front of his family merely for uttering the name of Muhammad. The abuses of blasphemy law in Pakistan are only too well known.

But the justification for blasphemy laws, as with many other censorious impulses, is increasingly tied up in the idea that people should be protected from offence, from controversy, even from being challenged.

Perhaps the most offensive notion is that we cannot deal with ideas, even aggressively expressed ideas, that we disagree with. Government’s such as Putin’s are all too happy to shut down free speech and repackage censorship as benign protection.

13 Jun 2013 | China, Digital Freedom

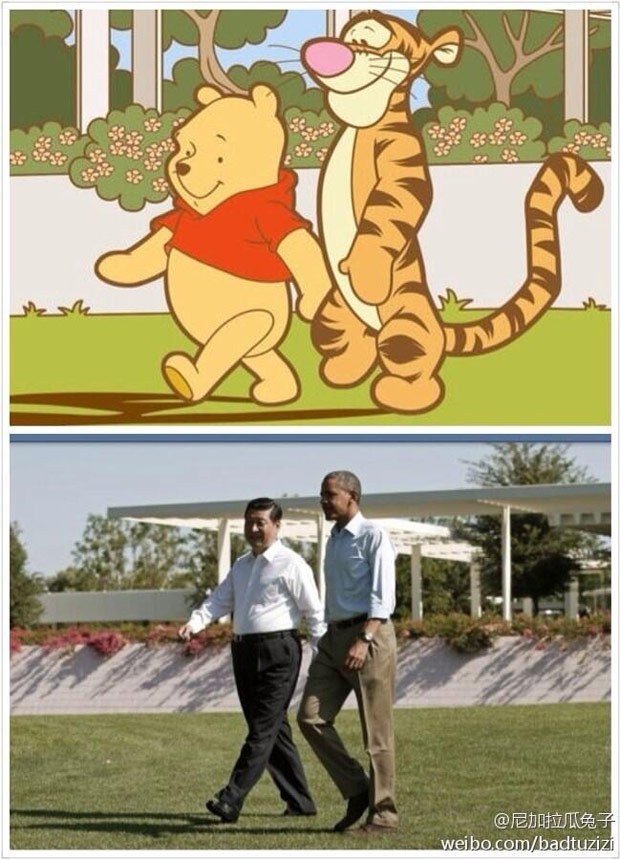

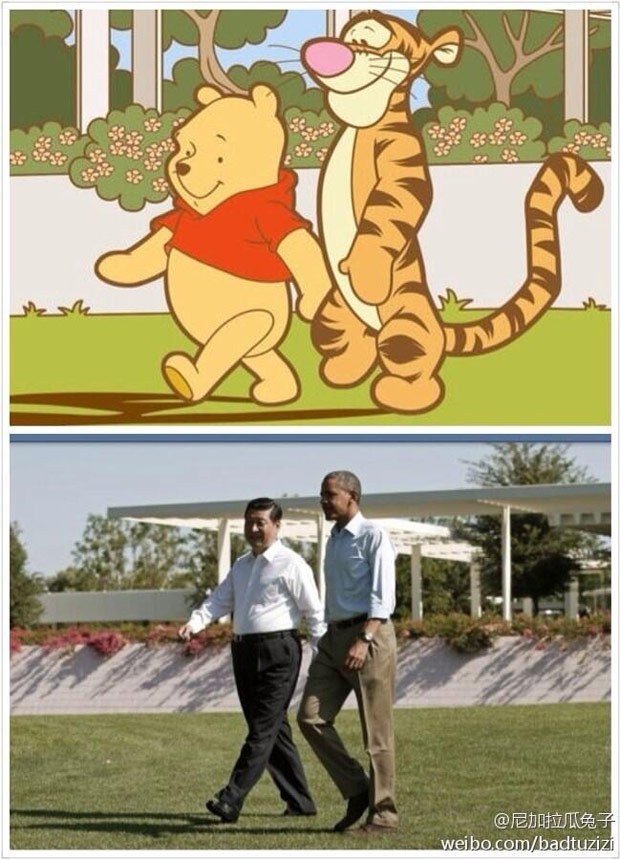

China has censored an image of Winnie the Pooh strolling with Tigger, after it went viral on popular Chinese microblogging site, Sina Weibo.

China has censored an image of Winnie the Pooh strolling with Tigger, after it went viral on popular Chinese microblogging site, Sina Weibo.

The image was circulated after bloggers noticed the similarities between a photo snapped this week of President Barack Obama and Chinese premier Xi Jinping and an illustration of the cartoon characters.

China’s censors are known for their lack of a sense of humour: earlier this month, censors deleted a photoshopped version of a famous picture showing a single protester standing before a row of tanks in Tiananmen Square, where the tanks were replaced with large rubber ducks.

Sara Yasin is an Editorial Assistant at Index. She tweets from @missyasin

13 Jun 2013 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia

Pussy Riot – videos of their “Punk Prayer” protest are blocked by Russian authorities

April saw a bizarre variety of sites blocked by the Russian authorities or internet service providers – among them Pussy Riot videos, Wikipedia, the Yandex search engine, Blogger blogs, sites promoting bribery and corruption, sites of land developers and the humorous anti-encyclopaedia Absurdopedia (the Russian version of Uncyclopedia). Even the parody website Gospoisk (gossearch.ru) was blocked. The site is a fake search engine, ostensibly created with government support: when a visitor types a query in the search box, he or she is asked to enter his first and last name, patronymic, passport details, address and the reason for the request. Compiled by Andrei Soldatov

(more…)

Ahmadinejad, the Islamic Republic’s sixth president, brought along with him an aggressive foreign policy and a penchant for controversial statements — from

Ahmadinejad, the Islamic Republic’s sixth president, brought along with him an aggressive foreign policy and a penchant for controversial statements — from