17 May 2012 | Asia and Pacific, Index Index, minipost

Lady Gaga has been refused a permit to play her sold-out concert in Indonesia following demonstrations from religious protesters. The permit for the Born This Way Ball, scheduled to take place on 3 June, was refused after Islamic hardliners, lawmakers and religious clerics spoke out against the pop star’s racy clothes and dance moves. Indonesian critics have said that the nature of the show could undermine the country’s moral fibre. Lady Gaga’s promoters in Indonesia will fight for the performance to go ahead, despite threats that protesters will use physical force to prevent her getting off the plane.

15 May 2012 | Middle East and North Africa

On 5 May the Bahraini regime arrested prominent human rights activist and 2012 Index award winner Nabeel Rajab for inciting violence on social networking sites. This is the second time Rajab has been arrested for so-called “cyber crimes”, and last year the regime accused him of publishing false information on Twitter.

These attacks on free speech illustrate how authoritarian regimes can use social media as a convenient “evidence-gathering” tool to prosecute those who dare speak out. Indeed, Rajab’s arrest is a warning shot to others: a reminder that engaging in online activism could result in a prison sentence.

While the fear of arrest is an important concern for many activists using social media, there are other factors at work that might deter people from criticising the Bahraini regime. One of these is trolling, an aggressive form of online behaviour directed at other web-users. It usually comes from anonymous accounts, and its severity can range from death threats and threats of rape, to spiteful comments and personal abuse. It is particularly common on Twitter. Here’s a little taster of what I’ve experienced:

@marcowenjones: ‘don’t you worry, we’ll cross paths one day. You’ll see, and I’ll remind of these days while my cock is inside u’ – Anonymous Troll

Human rights activists and journalists often find themselves being targeted by Bahrain’s internet trolls. Al Jazeera journalist Gregg Carlstrom tweeted: “Bahrain has by far the hardest-working Twitter trolls of any country I’ve reported on”. J. David Goodman of the New York Times writes about how internet trolls are attempting to ‘cajole, harass and intimidate commentators and journalists’ who are critical of the Bahrain government. Bahraini journalist Lamees Dhaif says that much of this trolling panders to Gulf Arab audiences, and that women are often accused of being promiscuous while men are accused of homosexuality.

For the thick-skinned, trolling might have no effect, but not everyone can brush it off so easily. Some users I have interviewed in the course of my PhD research have admitted that trolling has stopped them tweeting anything critical of the regime. Others have “protected” their Twitter accounts, which means that what they write can only be read by users approved by the author, thereby limiting their audiences. Trolling can therefore be seen as a type of bullying, one that uses intimidation to force people to engage in self-censorship. It is especially effective in times of political upheaval, when there is the constant threat of arbitrary detention or even torture. As Global Voices‘ MENA editor Amira Al Hussaini once said: “cyberbullying = censorship! Welcome to the new era of freedom in #Bahrain”.

Trolling in Bahrain has became so severe that a report commissioned to investigate human rights abuses in the country last year actually mentioned it. In particular, it focused on the actions of @7areghum, a Twitter account that “openly harassed, threatened and defamed certain individuals, and in some cases placed them in immediate danger”. The legal experts charged with compiling the report concluded that @7areghum broke Bahraini law and international law. Despite this, the Bahrain government do not appear to have asked the US government to subpoena Twitter to release information about the account.

Even harsh new laws designed to punish those guilty of online defamation seem little more than an attempt to intimidate those thinking of engaging in dissent. The insincerity of such laws is highlighted by the fact that the government are paying enormous amounts of money to PR companies to engage in clandestine activities to improve Bahrain’s image. Indeed, it appears that the managing director of one such company, which received 636,000 USD (approximately 385,000 GBP) to do PR work for the Bahraini government, runs a blog which routinely defames activists. The government seems happy to let this slide, further fuelling the belief that some internet trolls work for PR companies paid by the regime to spread propaganda and marginalise dissent.

Although it can be notoriously difficult to track down trolls and cyber-bullies, the government’s unwillingness to condemn the likes of @7areghum suggest tacit support of such methods. The recent announcement that the government would take action against all those who tarnish Bahrain’s image on social media also corroborates the notion that cyber laws only apply to those who oppose the regime. In the meantime, expect trolling to continue, for it is a useful form of devolved social control, one that allows the government to distance itself from accusations of censorship.

Marc Owen Jones is a blogger and PhD candidate at Durham University. He tweets at @marcowenjones

15 May 2012 | Middle East and North Africa

Six months after Tunisia’s first free elections, the country’s newspapers are filled with nostalgic longing for its former dictator. Even if his rule was a “veritable one-man-show”, muses La Presse, “was his dictatorship really harmful to Tunisia?” The accompanying hagiography leaves you in little doubt that this is meant as a question to which the answer is “no”. But there is no call for the dictator himself to be reinstalled. That is because the object of their affection is not the recently ousted President Ben Ali, but his predecessor, Habib Bourguiba, and he died 12 years ago.

At a time when the fundamental basis of the Tunisian state is up for grabs, the invocation of the dead president’s spirit is telling. There is a section of society — perhaps of a certain age — that remains faithful to the memory of Bourguiba as the father of a modern, secular Tunisia. The fact that he was also an autocrat who persecuted the political Islamists now leading Tunisia’s transitional government is not without significance. The tensions between the forces of secularism and the religious right have come to define the post-revolutionary era.

It is important that Tunisians are able to have these debates in public. “Tunisia was almost destroyed by two things, and they both begin with C,” says Afef Abrougui, Index on Censorship’s Tunisian reporter, “corruption and censorship.” Decades of state censorship have left the profession of journalism in a poor state of repair. Nevertheless, the sharp and occasionally shrill criticism of the present government, in print and online, is an obvious sign of progress. Artists and musicians are able to think aloud about politics without the police politique taking front row seats. Whatever the theatrical merits of Facebook!, a sort of cyber-Brechtian dance interpretation of the 2011 protests on show at the Centre Culturel de Carthage, its singular virtue must be that it can be shown at all.

In spite of these advances, there are some worrying noises. In March of this year, some drama students chose to celebrate World Theatre Day by performing on the steps of the Theatre Municipal, the grand art nouveau building in the middle of Avenue Habib Bourguiba in Tunis. At the other end of the street, a group of over-exuberant Salafists decided to put on their own piece of street theatre. As the denouement of their demonstration in favour of a religious constitution, a few of their number decided to clamber up the 120-foot high, wrought-iron clock tower at the end of the street, planting the black flag of the Caliphate at its summit. Their mission accomplished, they made their way down the road and set upon the students, noisily denouncing their “lack of respect for religious sanctity”, and raining down bottles on their heads.

When anyone feels the need to stage a counter-demonstration against theatre, it is time to sit up and pay attention. The craven response of the Interior Ministry, however, was to prohibit demonstrations on Avenue Habib Bourguiba altogether (the ban was subsequently lifted after several violent confrontations between police and protestors). Parts of the street are now semi-militarised zones; government buildings and public spaces are wreathed in barbed-wire. Groups of bored-looking military police sit in canary-yellow buses, waiting for something to happen.

Like Avenue Habib Bourguiba, there are still some areas of free expression that are only entered at acute personal risk. This month, Nabil Karoui, the general director of Nessma TV, was prosecuted and fined for “violating sacred values”. His offence was allowing the animated film Persepolis to be shown on his station (it depicts Allah as an old man with a white beard). The two imams who called for his death are yet to be punished.

A sentence of 7 ½ years imprisonment for two young men who published a satire of the prophet Mohammed was endorsed by President Moncef Marzouki. “Attacks on the sacred symbols of Islam”, he said, “cannot be considered part of freedom of expression.” The literal-minded censorship of the sacred has been accompanied by an equally disturbing increase in private prosecutions for obscenity. Earlier this year, the publisher of the national newspaper Attounissia was charged with “disrupting public order and decency” for printing a picture of a Lena Gercke, girlfriend of Real Madrid footballer Sami Khedira, on its front page. All these prosecutions have been brought under provisions of the Ben Ali-era criminal code, which remain on the statute book.

This creeping moral and religious censorship adds to the impression of a state slouching towards authoritarianism. In the name of national unity, the transitional government has time and again shown itself quick to curtail, and be slow to defend, the right of Tunisians to free expression. In the political turf war that is taking place in the country, there is a real danger that the forces of reaction will be permitted to mark out the boundaries of free speech in a way that imperils the advances of 2011.

Michael Parker is a London-based lawyer and writer on international and legal affairs.

14 May 2012 | Uncategorized

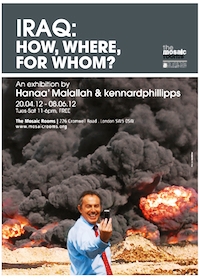

Transport For London has reinstated a banned ad campaign for London’s Mosaic Rooms gallery featuring an image of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair photographing himself on a mobile phone in front of an explosion.

The photomontage “Photo Op”, made in 2005 by kennardphillipps, was promoting a joint show at the gallery for them and Iraqi artist Hanaa’ Malallah called “Iraq: How, Where, For Whom?”

A passenger at Green Park station complained directly to TFL’s commissioner and CBS Outdoor — the company in charge of advertising on the London Underground — was instructed to remove all 100 A3 posters just as they were being put up.

CBS Outdoor claimed the image was in breach of bylaws that prohibit imagery that “contain images or messages that relate to matters of public controversy and sensitivity are of a political nature calling for the support of a particular viewpoint, policy or action or attacking a member of policies of any legislative, central or local government authority [advertisements are acceptable which simply announce the time, date and place of social activities or of a meeting with the names of the speakers and the subjects to be discussed].”

This weekend, when asked about the ban, TFL’s press office claimed no knowledge of it and subsequently issued the following statement:

“Our advertising contractors, CBS Outdoor, were instructed to remove the posters as they depicted a prominent politician during the pre-election period. Should the organisation concerned wish to display the posters again now the election has been held, we would be happy to do so.”

However, nearly two weeks of negotiations between the Mosaic Rooms and CBS Outdoor / TFL had already transpired. This resulted in the creation of an alternate ad campaign design featuring former US President George Bush. When asked if the Mosaic Rooms can now run the entire campaign with the original Blair image, TFL replied “yes.”

Artist Peter Kennard, of kennardphillipps, said at the time of the ban “It seems that for TFL, the Iraq War is not for us to think about and [Tony] Blair is not only beyond criticism, but his actions while he was in office cannot even be acknowledged. What affords him such protection when he is now merely another multi-millionaire businessman amongst many?”

As a charity under the Qattan Foundation, the Mosaic Rooms are entitled to a heavily discounted advertising rate in the London Underground. They contended that their posters asked a question and that TFL’s actions were a “clear act of censorship which removes a poster on purely political grounds while undermining the principles of free artistic expression.”

By saying that the Mosaic Rooms can reinstate the original poster campaign featuring “Photo Op” after banning it on clear political grounds, TFL have shown that they are easily influenced by structures of power. A well-placed passenger with access to the right people in their company can get a campaign taken down — and were the ban not challenged it would have continued. As such, TFL may have set a precedent for other charities and designers seeking to use more political imagery in their work and may think twice before censoring creative expression.

At the time of this writing, CBS Outdoor have still not received instruction from TFL to reinstate the original poster campaign and have proceeded with mounting an alternate image.