21 Aug 2015 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Lilian Lepère has filed a lawsuit against French media outlets for revealing where he was hiding during a standoff with the Charile Hebdo attackers. (Photo: YouTube / France 2)

Graphic designer Lilian Lepère hid under a sink for eight hours while the Kouachi brothers, Saïd and Chérif, on the run after attacking Charlie Hebdo, occupied the printing house where he worked in Dammartin-in-Goële (in the Seine-et-Marne region). Believing it was empty, the brothers hid in the factory for several hours before being killed by a special operations unit of the French armed forces.

While the designer was hiding, MP Yves Albarello (Les Républicains), during an interview with RMC radio, revealed Lepère was in the building. Television channels TF1 and France 2 repeated the information. The Kouachi brothers, who had smartphones and a radio, could have easily discovered Lepère’s presence.

French newspaper Le Parisien recently revealed that Lepère intends to sue RMC, TF1 and France 2 for revealing that he was hidden during the stand-off with the Kouachis. The newspaper reported that Lepère will contend in the suit that the media outlets put his life in danger. Last Thursday, 13 August, the Paris Public Prosecutor’s department opened an investigation.

This is not the first time French media has come under scrutiny for its treatment of the January attacks.

In February, the country’s broadcasting watchdog Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (CSA) distributed warnings to TV and radio stations, noting that 13 media outlets revealed live on air that a confrontation had begun between the police and the Kouachi brothers. Considering this a “serious failure”, the CSA said that the reporting “could have had dramatic consequences for the hostages of the Hyper Casher in Porte de Vincennes”, where Amedy Coulibaly, an accomplice of the Kouachi brothers, was holding hostages at a supermarket. Coulibaly was demanding that the brothers be released. The CSA also blamed TV channels for revealing that people were hiding during the two hostage crisis that took place on 9 January.

The CSA listed the broadcasters’ failings, reproaching them:

• The broadcasting of images showing the policeman being shot by the terrorists

• The broadcasting of elements allowing the identification of the Kouachi brothers

• The disclosure of the identity of a person suspected to be a terrorist

• The broadcasting of images and information regarding an operation still under way, as hostages were still being held in Dammartin-en-Goële and in the Hyper Casher in Porte de Vincennes

• The announcement that a confrontation with the terrorists was taking place in Dammartin-en-Goële while Amedy Coulibaly was still entrenched in Porte de Vincennes

• The divulging of information regarding people hiding in the places where the terrorists had been entrenched, while the assaults had not yet taken place and the hostages’ lives were therefore still at risk

• The broadcasting of images of the assault in the Hyper Casher store Porte de Vincennes

At the time, TV and radio channels contested the CSA’s decision, writing, in a joint letter entitled “Information under threat” that, “The freedom of the press is a constitutional right. Journalists have a duty to inform with rigour and precision. The CSA blames us for having potentially breached public order or taken the risk to fuel tensions within the population. We dispute this.”

They added: “How is it possible to think that, in 2015, the CSA wishes to reinforce the control on an already regulated French broadcasting media while information circulates without constraint in the written press, on foreign channels, all social media and websites? Aren’t they placing us in a situation of inequality in front of the law?”

In a similar story that took place in March 2015, the six people who hid at the Hyper Casher, where Amedy Coulibaly killed four people, filed a complaint against an unknown person for putting their lives in danger. The complaint was directed at the media and specifically at BFMTV, Patrick Klugman, a lawyer representing the group, told Le Parisien. BFMTV revealed that a woman might of been hiding within the Hyper Casher.

“The disclosure of the presence of these people who were hiding, in the middle of a hostage crisis, is a failing that cannot remain unpunished, and all the more so because we knew that the terrorist was watching the TV channel. An information, even if it is accurate, must not put lives in danger”, Klugman said.

Speaking with Le Nouvel Obs, Christophe Bigot, a lawyer who specialises in media, explained that even if an investigation has been opened, because the story had stirred a lot of emotions at the time, Lilian Lepère’s complaint has little chance to succeed.

“The principle, when it comes to the press, is freedom of expression. It has precise limits determined by law, such as libel or the broadcasting of fake information likely to disrupt public peace. In this case, none of these limits can be pointed out. For the media, several complaints could nonetheless be an occasion to examine how to reconcile immediacy of information and ethics,” Bigot said.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

Related:

• Targeted cartoonists show support for Charlie Hebdo

• Stand up for free speech. Publish Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons

• Don’t let free speech die

• How cartoonists responded to the attack on Charlie Hebdo

This article was posted to indexoncensorship.org on 21 August 2015

30 Jul 2015 | Events

Secret Forum at Wilderness Festival

Leading cartoonists step into the ring with heavyweight commentators for a quick-thinking, rapid-fire, free speech fight club: should anything be off limits for cartoonists?

Featuring:

- Dave Brown (the Independent)

- Tayo (Nigeria)

- David Aaronovitch (The Times)

- Sameer Rahim (Prospect Magazine)

When: Sunday 9th August, 4.30pm

Where: Secret Forum, Wilderness Festival, Oxfordshire (Map/directions)

Tickets: available via Wilderness Festival

Presented in partnership with Sunday Papers Live

7 May 2015 | Denmark, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features

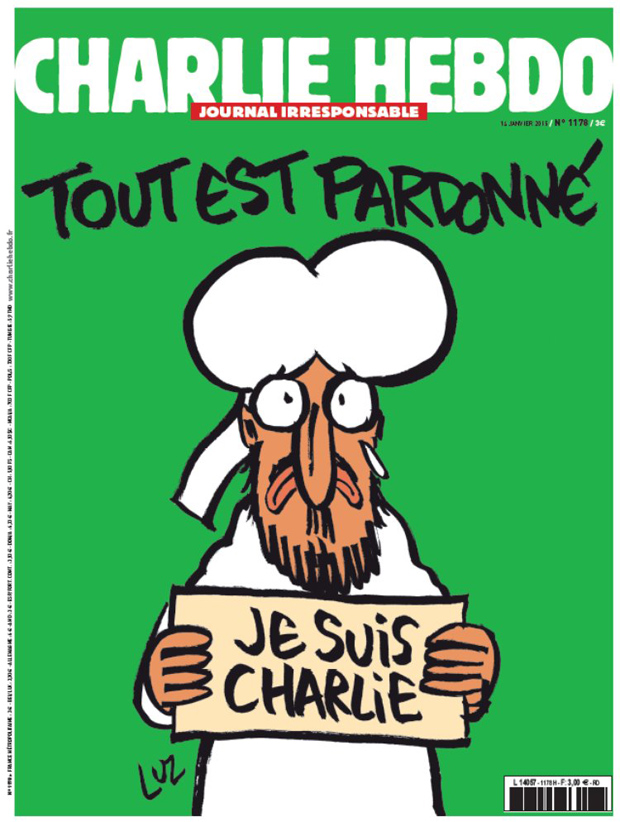

Tout est pardonne or All is forgiven, the first post attack cover of Charlie Hebdo

It’s now almost ten years since Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a set of cartoons, some of which (though by no means all) depicted the Islamic prophet Mohammed. Some were flattering, some were not. One mocked jihadist suicide bombers. Another showed a schoolboy called Mohammed calling Jyllands-Posten’s editors bigots.

The idea came after it was reported that a Swedish children’s author could not find someone to illustrate her book on the life of Mohammed. Flemming Rose of Jyllands-Posten decided to commission cartoonists to draw the apparently taboo figure.

As an exercise in taboo-busting, it was bound to be controversial. But controversial though some were (one showed the prophet as a scimitar wielding menace, another a figure with a bomb for a turban) they were not shocking enough for the Danish-based radicals who decided to make a campaign of the issue. In an astonishing act of chutzpah (there really is no other word), Ahmad Abu Laban decided to fill out a “dossier” on the cartoons with even more offensive characterisations, some of which had nothing to do with Mohammed at all. He and his colleague Ahmed Akkari took the dossier to the Middle East, apparently to prove the level of anti-Muslim hatred in Denmark. Chaos ensued. The rest, the usual line would go, is history. But that wouldn’t be true: the “rest” is very much the present, and perhaps pressing now more than at any time in the past 10 years.

One wonders if Ahmad Abu Laban quite knew what he was getting us all in to. Certainly, the man, who died in 2007, was of what is now a familiar figure in western Europe. The self-publicising Muslim spokesman: the go-to guy for a controversial quote for a press not quite sure of the heat of the flames with which they were playing. Omar Bakri Muhammad, for example, was first introduced to the British public as a ridiculous fantasist in Jon Ronson’s documentary The Tottenham Ayatollah. His proteges in al-Muhajiroun provided a steady flow of enjoyably ridiculous bogeymen such as Anjem Choudary and Abu Izzadeen, who in 2006 was given the main interview on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. Subsequent news bulletins carried his warnings of “Muslim anger” as if he were some sort of pope, rather than a fringe figure with highly dubious links.

Everyone enjoyed these outrageous figures for a while, until we realised the damage they could do. Practically every home-grown jihadist in Britain has had dealings with al-Muhajiroun. The late Laban may have known of the chaos he was about to unleash on the Middle East in 2006 with his dossier, and indeed the world ever since. He may not. His former comrade Akkari repented in 2013, saying: “I want to be clear today about the trip: It was totally wrong. At that time, I was so fascinated with this logical force in the Islamic mindset that I could not see the greater picture. I was convinced it was a fight for my faith, Islam.”

Well good, but a little late now.

Since 2005 we have been embroiled in an absurd abysmal dream. Some people draw cartoons of a long-dead religious figure. Some other people decide this has offended some sacred, though undefined, law, and so they decide that the people who drew the cartoons must be killed. Repeat. What chronic stupidity.

But of course there’s more going on here. There is more than one reason to draw or publish Mohammed drawings: from plainly making a free speech point (as many publications did after the Charlie Hebdo murders), to anti-clericalism (a la Charlie itself), to deliberate antagonism towards Muslims (a la Pamela Geller). Not all Motoons are the same.

Nor are all responses on the same spectrum. There is a world of difference between the average Muslim who may be annoyed by a portrayal of Mohammed and a jihadist who takes it upon himself to find people who have drawn these portrayals and kill them or attempt to kill them.

This is the error that has plagued the debate for the past 10 years, and came to light again in the past few weeks with PEN’s awarding of a prize to Charlie Hebdo, and the attack on a Pamela Geller-organised rally in Texas which featured a “draw Mohammed” competition.

There has been an unwitting acceptance of several dangerous ideas, chief amongst them that in order to have respect for someone as a human being, one must respect all their beliefs, and observe their taboos. But as novelist and long-time PEN activist Hari Kunzru put it: “It is not solidarity with the oppressed to offer ‘respect’ to an idea just because it’s held by some oppressed people.”

Following from this is the idea that all expression that disrespects beliefs and taboos must be driven by bigotry and racism, and that to stand against bigotry and racism is to stand against any such expression. There is a sad irony in this failure to discriminate.

On the reverse of this, some Muslims feel that free speech is now something that is being used to batter them over the head, rather than protect them. This in itself is a failure of civil society: the moment we decide everyone with a certain background and set of beliefs can be put in the “Muslim” box is the moment we ensure that those who shout loudest about those beliefs — the “extremists” — are given status. Ahmad Abu Laban, for example, claimed that his Islamic Society of Denmark represented all Danish Muslims.

So now what? As we’re approaching 10 long years of this argument, is there hope for resolution any time soon? I fear not. There can be no accommodation between those who believe in the right to free expression and those who believe “blasphemy” should carry the death sentence.

In between, if it does prove impossible not to take sides, we can at least make sure our arguments are clear and our ears are listening.

This article was posted on 7 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

1 May 2015 | Denmark, European Union, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Macedonia, mobile, News and features, Poland, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom

As we approach World Press Freedom Day, the right to freedom of expression will again be celebrated as an inalienable European value across the continent — by the public, the media and politicians alike. But to many, this will mean little more than engaging in a well trodden mental routine. We hardly consider the difficulties that freedom of expression faces in practice.

In the first part of 2015, more than a third of journalist killings in the word took place in two European countries; France and Ukraine. If it is true that Europe’s reactions to the Charlie Hebdo attack — the majority of them very emotional — were salubrious, they simultaneously gave rise to ambiguous situations. Many of the leaders that will on 3 May reaffirm their commitment free expression, supported the same message by taking part in the historic march in Paris on 11 January.

But upon seeing Angela Merkel, some were also reminded that Germany continues to treat blasphemy as a crime — as do Denmark, Spain, Poland and Greece, among others. Ireland, whose Enda Kenny was also in attendance, has a constitution which specifically mentions blasphemy and in 2010 enacted a new law against it. All these European countries defend themselves by saying that they do not apply their laws against “blasphemers”. That argument does not carry much weight when it comes to opposing those countries — Saudi Arabia, Iran, various Asian countries — that have tried to turn blasphemy into a universal crime recognised by the UN.

Spain’s Mariano Rajoy too marched in solidarity, but his government has taken steps to promote changes in the penal code that would “represent a serious threat to freedom of information, expression and the press”.

And what was Viktor Orban doing in Paris? The Hungarian president has reunified Hungary‘s public media so as to better bind them to his own party. Despite being the leader of an EU country, Orban has followed Vladimir Putin’s example. In this experimental model, the Andrei Sakharov Center and Museum is no longer ordered to close as it was in the old days, but rather fined 300,000 roubles (€5,000) for failing to register as a “foreign agent”. One day brings an announcement of compulsory registration for bloggers in Russia; another day, harassment against Russian and Hungarian NGOs perceived as “unpatriotic”.

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutohlu traveled to Paris, only to later label Charlie Hebdo’s post-attack issue a “provocation”. A reminder: Turkey is an EU candidate country where dozens of journalists have been sentenced to prison, and where various internet sites, including those that dared to reproduce some of Charlie Hebdo’s caricatures, have been blocked.

But also present at the march, were various representatives of European journalists — myself included. Just behind the Charlie Hebdo survivors, we carried a banner with the message “Nous sommes Charlie”.

Walking next to me was Franco Siddi, of the Italian National Press Federation. He talked to me about how imprisonment for defamation is still a possibility in Italy, though the European Court of Human Rights has ruled it a disproportionate punishment.

In my home country Spain too, this possibility of imprisonment remains, even if under Spanish jurisprudence freedom of expression consistently prevails over the demands of plaintiffs. In Italy, the situation is the same, yet my Italian colleagues point out that in 2014 alone, 462 journalists in the country were threatened with legal action for alleged acts of defamation. And while the current proposal for reform being considered foresees eliminating the possibility of jail time, it increases the potential fines.

This is not the only potential legal threat facing European journalists. Long before 9/11, there existed a reflexive habit of passing “urgent” laws under security pretexts, as in the UK during the most difficult years of the Northern Ireland conflict. The current model is the United States’ Patriot Act, which has recently been discussed in France. Meanwhile, in Britain and Spain are debating what free expression activists describe as “gag laws”. In Macedonia, the sentencing of the investigative journalist Tomislav Kezarovski to two years in prison under one of these security inspired laws stands out as a warning sign.

Against this worrying backdrop, across Europe journalists, freedom advocates, campaigners and even politicians are standing up for press freedom. When Gvozden Srecko Flego, member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, recently highlighted the cases of Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Azerbaijan as particularly problematic, he also suggested a countermeasure. He recommends “organising annual debates […], with the participation of journalists’ organisations and media outlets” in the respective parliaments of each state.

Media concentration, one of the most serious challenges to media pluralism and free expression in Europe, is being tackled. One proposal, which some international bodies have already accepted, would create a “Media Identity Card” requiring owners to publicly identify themselves and thus create an environment of more open and transparent media ownership.

When defending freedom of expression as a European value, we cannot allow ourselves to simply fall in into mental routines. This World Press Freedom Day we need both words and actions.

Paco Audije is a member of the Steering Committee of the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This column was posted on 1 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org