30 Apr 2015 | mobile, News, United Kingdom

What if your job, your career, was winding up an entire nation?

That’s it. Sure, you have a column in a national newspaper. But what can you really do with it? You can’t really share your thoughts on the common toad, or tell delightful stories about your children misunderstanding foreign words, much less offer some insight into the workings of the modern world. Sure, you can chuck the odd piece of light relief in the sidebar or the basement, but that’s not what people are here for. We’ve come to your column to be thrilled by your outrageous views, and thrilled we will be.

Last time round it was people giving food to, and receiving food from, charity.

“SAY the words food bank” La Dolce ‘Opkina began, “and I am supposed to put on my concerned face and proffer up a can of beans.”

Where’s this going Katie? Where could this possibly be going?

“But all I’ve found in the back of my cupboard is two fingers. And they don’t belong to a Kit Kat.”

BOOM! Gotcha. I mean, it makes no sense. If it’s the fingers at the end of her arm she’s using, why are they in the back of the cupboard? Unless, maybe, she is SO outrageous that she keeps a special V-flipping apparatus in her cupboard, as her doctor has advised her that the constant extension and retraction of her index and middle finger was putting her in serious risk of chronic RSI. But then, if you were using it that much, you wouldn’t keep it in the back of the cupboard. You’d have it on the hall table, perhaps. Or in a little belt-mounted pouch, like a techie’s mobile phone, ready to unleash, cosh-style, upon passing do-gooders, bed-wetters, namby-pambies, oiks, poshos, hippies, liberal elitists, ignorant yokels, EUROCRATS, trendy vicars, Trots, gypsies, useless husbands, trashy wives, “gay rights” activists, lesbo-feminists and everyone else you might bump into at a reasonably-sized community festival in a reasonably-sized town.

It must be exhausting keeping track of this roll call of resentment. It must be wearing to have to be angry every week. How draining to have a public persona dedicated to hating everything and everyone.

And then there is the fact that outrage is a substance which can be addictive, but to which people can also develop a considerable tolerance. In order to keep us interested — and quite possibly to keep herself interested also — Hopkins has to keep upping the dose, until eventually we get to the point where she’s describing poor African people drowning in the sea as cockroaches and everyone suddenly stops and thinks “oh”.

The problem the serial controversialist who has nothing else to trade on faces is that the only way to go is down. The very nature of the job and the stuff you are peddling means you must, inevitably, end up overstepping the mark. In the case of Jeremy Clarkson, a carnival of boorishness ended in violence, where it had to. Hopkins seems to have survived, but she’s Zugzwanged herself: tone down the schtick and she becomes pointless; the only other move available is directly into the abyss. This is the fate of the wind-up merchant.

The exception to this rule is the satirist. The essential difference between the satirist and the controversialist is that the controversialist puts herself forward, from the beginning, as the stoic truthteller, striving alone in a world gone mad. Controversialists tend to be declinists: the world is steadily getting worse. The converse of this is the belief that at some point, usually in the period of the controversialist’s late adolescence, the world was right.

Satirists hold out no such (perverse) hope. The world is awful, the world has always been awful, and the only way to get through it is to laugh and hope we can make some tweaks around the edges. It is curious then, that from Private Eye to Charlie Hebdo, satire is often linked to campaigning journalism in the same publication.

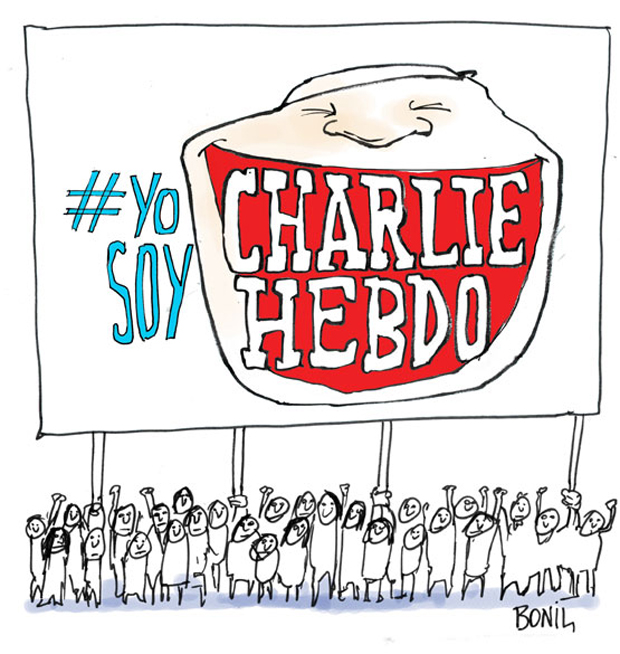

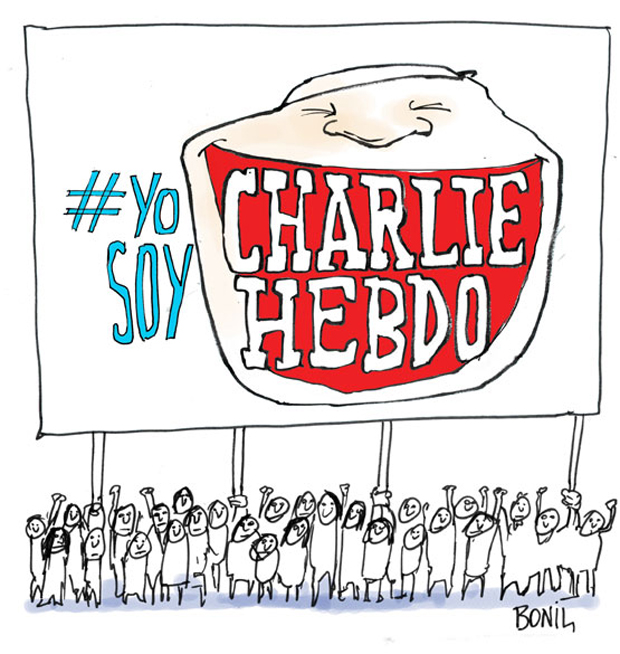

Charlie has once again been in the news after several US-based authors refused to take part in a gala in honour of the magazine hosted by PEN American Center.

The writers’ heckles were raised by what they saw as racist cartoons run by Charlie in the past. Among these were one of a black politician portrayed as a monkey, and Nigeria girl victims of Boko Haram portrayed as “welfare queens”. Of course, at face value, these seem racist (though it is worth noting that it was not racist cartoons that saw Charlie’s staff slain: it was cartoons that refused to obey religious taboo).

What the US critics failed to acknowledge was that all satire is reactive: the cartoons did not simply spring unprompted from the cartoonists’ pens. The case of the ape cartoon was a reaction to far right portrayals of the minister, and the accompanying text very clearly mocked the Front National’s leader Marine Le Pen. As Irish novelist and Charlie columnist Robert McLiam Wilson pointed out:

“Without the snipped-off text underneath, and the knowledge of the lamentable tosh it was lampooning, of course Charlie would seem racist. It would seem racist to me too. But to strip the image of its fundamental components like this is akin to saying the incomparable Jonathan Swift was a baby-eating Nazi and that A Modest Proposal was actually a cookbook.”

Satire must toy with what it sets out to mock: otherwise it is meaningless and unintelligible. Sometimes the controversy of the likes of Hopkins and the irony of Charlie can look, at first glance, identical.

And sometimes not: While Hopkins was describing “cockroaches” drowning in the Mediterranean, Charlie was echoing the refrain of many: “A Titanic every week,” with a cartoon depicting a white woman singing My Heart Will Go On while a despairing migrant begs her to “shut up” (Ta Guelle).

Bracing? Sure. But humanising, too. As satire should be and controversialism never is.

This column was posted on 30 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Apr 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović, at the Permanent Council in Vienna, 16 January 2014. (Photo: OSCE)

Anniversaries and commemorations are times to reflect, judge and move forward. So it is with World Press Freedom Day, which we note for the 22nd time this year amid worldwide evidence of hostility toward the media.

The date of 3 May was set aside by the UN General Assembly in 1993 to foster free, independent, pluralistic media worldwide.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the largest regional security organisation in the world, just four years later in 1997 created the position I now hold, the Representative on Freedom of the Media. The position was established expressly to help countries that are members of the organisation (which includes all of Europe, the countries of the former Soviet Union and Mongolia, as well as the United States and Canada) implement their promises to uphold the rights to free expression and free media.

It is my job to advocate for these two concepts. It is also my job to help, cajole and sometimes plead with the 57 nations in the organisation to simply live up to their promises to provide the environment in which free expression and free media can flourish.

Over the past 18 years only three people have held the position of Representative. As I enter my sixth and last year in this position, the time has come to reflect on the state of media freedom and to analyse the overall health of free expression across the OSCE region.

To do so, I needed a base from which to judge. I found that by returning to the very first public statement issued by the Representative’s office, then headed by German politician Freimut Duve, on 7 September 1998. It announced, ironically, that Duve had been denied a visa by authorities in Belgrade to visit the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, to lobby the government to change its policy of denying visas to reporters from other countries, some of whom were considered foreign intelligence agents.

The Helsinki Final Act of 1975, the very document that eventually brought the OSCE into existence, expressly called for improving the working conditions for journalists, which included examining “in a favorable spirit and within a suitable and reasonable time scale requests from journalists for visas” and to “grant to permanently accredited journalists…on the basis of arrangements, multiple entry and exit visas for specified periods”.

Duve wrote in the public statement: “Tito himself, as President of the former Yugoslavia, signed in 1975 his country’s acceptance of the principles and commitments of the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe.”

Those commitments expressly included the right of journalists to work internationally.

Promises made. Promises not kept.

Have things changed over the years?

The fact that you are reading this posting identifies you as someone well aware of the precarious position journalists and the media find themselves in today. They face a litany of problems, none of which is bigger than the issue of life itself.

The year 2015 hardly had started when eight journalists for the French magazine Charlie Hebdo were murdered in their office in Paris – over the depiction of a religious figure. Two weeks later, a discussion group in Copenhagen convened to talk about the Paris incident came under gunfire with another person killed. So much for free media. So much for free expression.

But we all know that while homicidal violence against journalists is the most drastic form of attack on free media, it is not the only one. Across the OSCE region media is subject to all nature of offences: criminal defamation laws that put reporters in jail for rooting out corruption in public places; cyber-attacks that plague internet media sites; new laws that are being adopted to criminalise free expression in the name of fighting terrorism; and increasing regulation of the internet in an effort by authoritarian governments to squelch media and free expression advocates.

The simple violations of media rights continue, too. In the past 12 months I have written to authorities and issued public statement on at least six occasions condemning the refusal of governments in the OSCE region to grant visas to foreign-based reporters. Have things really changed in 2015 from 1998? Only the countries involved; not the practices.

But even if my judgment on the past 18 years is harsh, media freedom advocates, such as me, must continue to move forward and provide the defenses necessary for free expression and free media to flourish. Complacency is not an option.

Solidarity, however, is.

For example, three rapporteurs on free expression from the United Nations, the Organization of American States and the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights and I annually issue a joint declaration on a topic related to free expression. Those declarations now are seeing their way into decisions of national and international bodies, including judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. This is real progress. Decisions upholding citizens’ rights under Article 10 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms are real results.

And all of us must continue to raise the issue of the rights of media before national legislatures. Public awareness campaigns on behalf of media can be effective tools to prod elected officials to spend the resources, including political capital, necessary to build environments conducive to free expression. Elected officials and their appointed, often nameless and faceless bureaucrats, can be taught and encouraged to write good laws and appoint good law enforcement authorities, including police, prosecutors and judges, to interpret those laws in a fashion that will provide oxygen for those who champion free expression.

It is easy to become disillusioned and depressed by the daily fare of media issues. We should recognise the perilous state of free media and free expression in many spots in the world. But we never should lose our focus. We should take note of this date and make a personal commitment to stand for the basic human rights of free expression and free media – this year and the next and the years after that.

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This column was posted on 29 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Apr 2015 | Campaigns, France, mobile, News, Statements, United Kingdom, United States

The decision by six authors to withdraw from a PEN American Center gala in which Charlie Hebdo will be honoured with an award once again emphasises the dangerous notion that some forms of free expression are more worthy than others of defending.

Charlie Hebdo was offensive to many — but as PEN points out — it was also vigorous in its defence of the importance of free speech, even in the face of those who would seek to silence that view through violence.

“Free speech for all can only be protected by standing up as vigorously – if not more vigorously – for the views you disagree with as those with which you agree,” said Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “If we don’t do that, freedom becomes something only for the favoured and powerful.”

Below Index republishes an article from CEO Jodie Ginsberg written a week after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo that addresses the importance of a defence of free speech in all its forms.

If you said “I believe in free expression, but…” at any point in the past week, then this is for you. If you declared yourself to be “Charlie”, but have ever called for an offensive image to be removed from public viewing, then this is for you. If you “liked” a post this week affirming the importance of free speech, but have ever signed a petition calling for a speaker to be banned, then this is for you.

Because the rush to affirm our belief in free expression in the wake of Charlie Hebdo attacks ignores a simple truth: that free speech is being eroded on all sides, and all sides are responsible. And it needs to stop.

Genuine free expression means being able to articulate thoughts, feelings and ideas without fear of harm. It is vital because without it individuals would be subject to the whim of whichever authority dictated what ideas and opinions – as opposed to actions – are acceptable. And that is always subjective. You need only look at the world leaders at Sunday’s Paris solidarity march to understand that. Attendees included Ali Bongo, President of Gabon, where the government restricts any journalism critical of the authorities; Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, whose country imprisons more journalists in the world than any other; and the UK’s David Cameron, who declared his support for free expression and the right to offend, while his government considers laws that could drive debate about extremism underground.

It is precisely the freedom for others to say what you may find offensive that protects your own right to express your views: to declare, say, your belief in a God whom others deny exists; or to support a political system that others dismiss. It is what enables scientific and academic thought to progess. As soon as we put qualifications around “acceptable” free expression, we erode its value. Yet that is precisely what happened time and again in response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks, with individuals simultaneously declaring their support for free expression while seeming to suggest that the cartoonists and anyone else who deliberately courts offence should choose other ways to express themselves – suggesting that the responsibility for “better” speech always lies with the person deemed to be causing offence rather than the offended.

“The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write and print with freedom…”

French National Assembly, Declaration of the Rights of Man, August 26, 1789

Index believes that the best way to tackle speech with which you disagree, including the offensive, and the hateful, is through more speech, not less. It is not through laws and petitions that restrict the rights of others to speak. Yet, increasingly, we use our own free speech to call for that of others to be limited: for a misogynist UK comedian to be banned from our screens, or for a UK TV personality to be prosecuted by police for tweeting offensive jokes about ebola, or for a former secretary of state to be prevented from giving an address.

A project mapping media freedom in Europe, launched by Index just over six months ago, shows how journalists are increasingly targeted in this region, including – prior to last week’s incidents – 61 violent attacks against the media. Globally, the space for free expression is shrinking. We need to reverse this trend.

If you genuinely believe in the value of free speech – that all ideas and opinions must be heard – then that necessarily extends to the offensive and the vile. You don’t have to agree with someone, or condone what they are saying, or the manner in which it is said, but you do need to allow them to say it. The American Civil Liberties Union got this right in 1978 when they defended the rights of a pro-Nazi group to march in Chicago, arguing that rights to free expression needed apply to all if they were to apply to any. (As did charity EXIT-Germany late last year, when it raised money for an anti-fascism cause by donating money for every metre walked during a neo-Nazi march).

Countering offensive speech is – of course – only possible if you have the means to do so. Many have observed, rightly, that marginalisation and exclusion from mainstream media denies many people the voice that we would so vociferously defend for a free press. That is a valid argument. But this should be addressed – and must be addressed – by tackling this lack of access, not by shutting down the speech of those deemed to wield power and privilege.

Voltaire has been quoted endlessly in support of free expression, and the right to agree to disagree, but British author Neil Gaiman, who discusses satire and offence in the winter Index magazine, also had it right. “If you accept — and I do — that freedom of speech is important,” he once wrote, “then you are going to have to defend the indefensible. That means you are going to be defending the right of people to read, or to write, or to say, what you don’t say or like or want said…. Because if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

This article was originally posted on 12 January 2015 and reposted on 27 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Feb 2015 | News, United Kingdom

How does one avoid being a potential target for murder by a jihadist? If you’re Jewish, you probably can’t, unless you attempt to somehow stop being Jewish (though I suspect, much like the proto-nazi mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, IS reserves the right to decide who is a Jew).

Everyone else? Well, we can be a little quieter. We can, perhaps, not hold meetings with people who have drawn pictures of Mohammed. We can, perhaps, recognise that the right to free speech comes with responsibilities, as The Guardian’s Hugh Muir wrote. The responsibility to be respectful; the responsibility not to provoke; the responsibility not to get our fool selves shot in our thick heads.

This seemed to be the message coming after last weekend’s atrocity in Copenhagen. Oddly, I just found myself hesitating while typing the word “atrocity” there. Felt a little dramatic. Because already, amid the condemnations and what ifs? and what abouts? that have dogged us since this wretched year kicked into gear with the murders in Paris, already, the pattern seems set. Young Muslim men in Europe get guns, and then try, and for the most part succeed, in killing Jews and cartoonists, or people who happen to be in the same room as cartoonists. Then the condemnation comes, then the self-examination: what is it that’s wrong with Europe that makes people do these things? The things we definitely know are wrong are inequality and racism, so that’s where we focus our attentions. Europe’s past rapaciousness in the Middle East, or its recent and current interventions: these, on a societal level, are believed to be mistakes, so they too, must be examined (it could be argued that non-intervention, particularly in Syria, has been at least as much of a factor).

What else? Maybe we caused offence. Maybe we crossed a line when we allowed those cartoonists to draw those pictures. Maybe that’s it. We’ve offended two billion or so Muslims, and of course, some of them are bound to react more strongly than others. So we’d best be nice to them in future (we leave the implied “or else” hanging). And being nice means not upsetting people.

This is, as I’m fairly certain I’ve written before, a patronising and divisive way of looking at the world. Patronising because of the casual assumption that Muslims are inevitably drawn to violence by their commitment to their faith, and divisive both because it sets a double standard and because it entrenches the notion that Muslims are somehow outside of “us” in European society.

That divisiveness is not merely useful to xenophobes and Islamophobes. It is equally important in the agenda for many types of Islamist.

Take a small but instructive example. The BBC Two comedy Citizen Khan is possibly the most normal portrayal of Muslims British mainstream comedy has ever seen. The lead character started life as an absurd “community leader” in the brilliant BBC 2 spoof documentary Bellamy’s People, before morphing into an archetypal bumbling silly sitcom patriarch in his own successful show.

Citizen Khan is a classic British sitcom in which the family happen to be practicing Muslims. It is not cutting-edge comedy, boldly taking on racial and religious blah blah blah; it’s family entertainment.

Cause for celebration, surely, that practicing Muslims are being portrayed as normal people rather than radical weirdos? Not according to the risibly-titled Islamic Human Rights Commission, a small group of Ayatollah Khomeini fans who have nominated Citizen Khan for its annual Islamophobia award, claiming the show features “Muslims depicted as racist, sexist and backward. Obviously”. They don’t want to see Muslims on television as normal people, because that would undermine the division they seek to engender. I doubt any of the people at the IHRC who suggested Citizen Khan was Islamophobic are genuinely hurt or offended by the programme; if they are, it’s because it features a portrayal of Muslim people, by Muslim people, that they cannot control. It’s really got nothing to do with “offence”.

Likewise, I refuse to believe that the killers of Paris or Copenhagen have been sitting around stewing for years over “blasphemous” cartoons. To imagine that these murders took place because of perceived slight or offence is to cast them as crimes of passion. I don’t buy it. These were, at best in the eyes of the killers, legal executions for the crime of blasphemy, carried out because their interpretation of the law demanded that they do so.

The same interpretation of the law means that these men are allowed, mandated even, to kill Jews. So that is what they do.

However much cant we spill about “no rights without responsibilities” (that is, the preposterous “responsibility” not to offend), the fact that people are being murdered for who they are rather than what they did should make us realise that there is no responsibility we can exercise that will mitigate the core problem: a murderous totalitarian ideology has taken hold. It has territory, it has machinery, it has propaganda, and it has a certain dark appeal, just as totalitarian ideologies before have had. ISIS or Daesh or whatever you choose to call it is calling people to its cause. AQAP competes for adherents.

Some will point to the previous violent criminal records of the killers in Paris and Copenhagen and say “You see? They were mere thugs: the ideology barely comes into it.” But come on, who do you think the Brownshirts recruited? Bookish dentists? The fact that thugs are drawn to a thuggish ideology mitigates neither.

This week, Denmark’s only Jewish radio station went off air due to security concerns. This is where responsibilities before rights leads us. Shut up, keep quiet, and if something happens then it’s your fault for being irresponsible. Irresponsible enough to wish to practice your culture and religion freely. Irresponsible enough to “offend” murderers with your very existence. This line of thinking is not just cowardly, it is accusatory.

The correct answer to the request that we show responsibility with our rights, is, as revolutionary socialist James Connolly put it, “a high-minded assertion” of rights themselves. Not just the right to speak freely, but the right to live freely.

This article was posted on 19 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org