16 Feb 2015 | Draw the Line, mobile

Growth can only happen when old obsolete ideas are replaced with newer, relevant ones. If we don’t challenge the established system of thought, we can’t move forward. If ideas that don’t work anymore aren’t rejected, new ones won’t find space. Without new and better ideas there is no movement in any field. Freedom of speech and expression is fundamental to that forward movement and as Salman Rushdie said, “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist”

We opened up the debate with Charlie Hebdo on our minds. The Hebdo massacre changed the world. Now there is an actual discourse on free expression across the globe. The world is coming together and expressing themselves collectively. Our twitter feed is proof of that. While a lot of people believe that the right to offend comes with the right to free expression, there are people who say that anything that leads to violence is wrong, and there is a fine line there which needs to be observed.

This is where we draw the line: somewhere in the ever-changing grey area between absolutism and stagnancy.

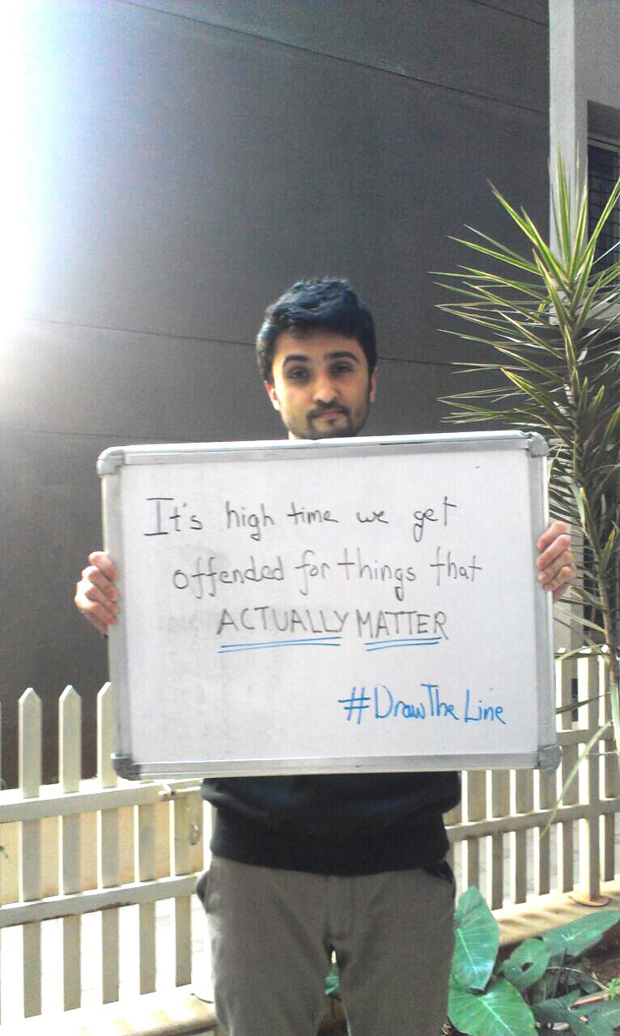

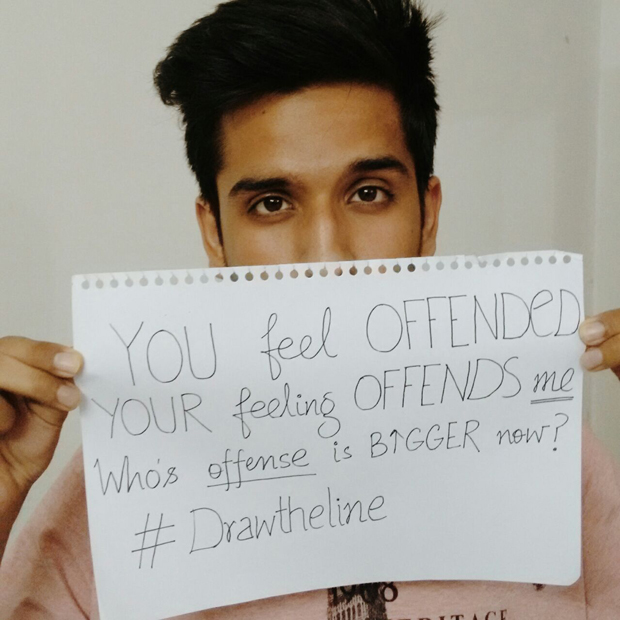

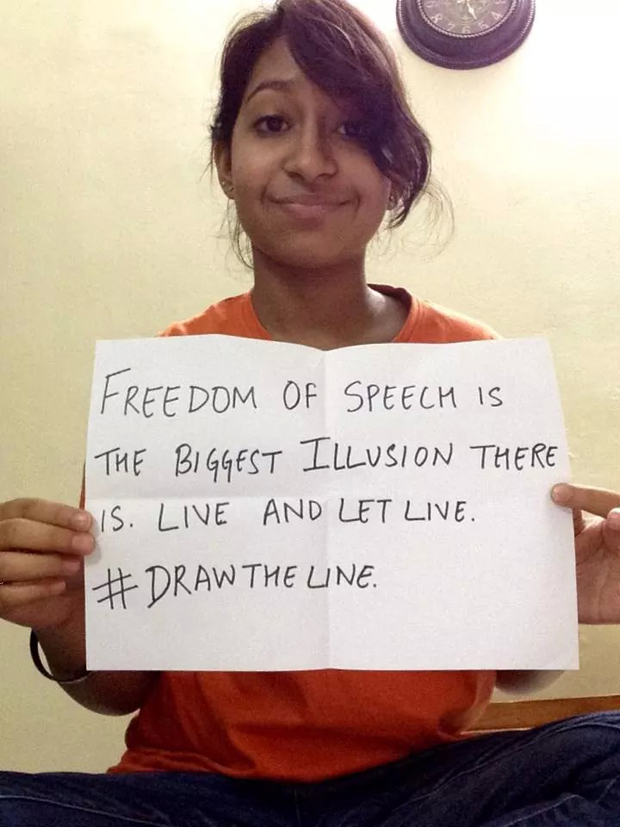

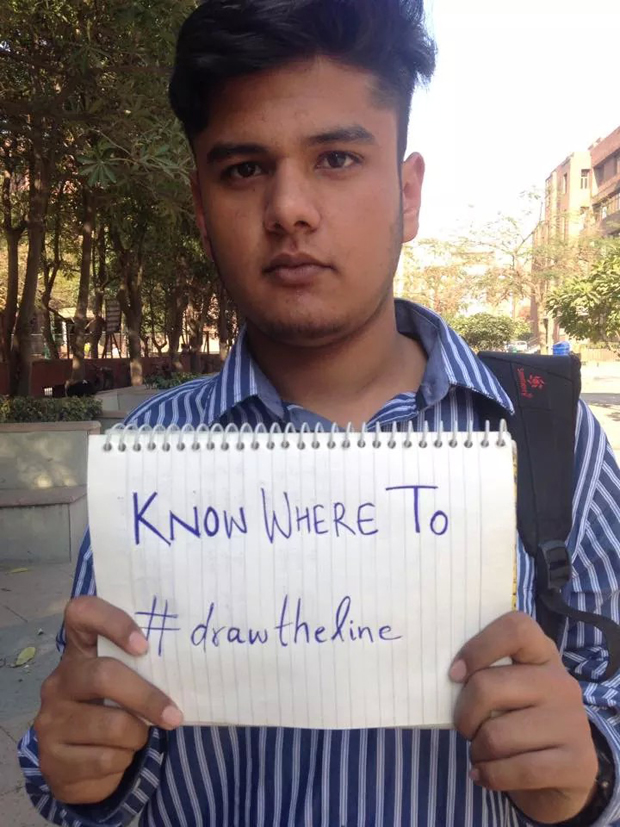

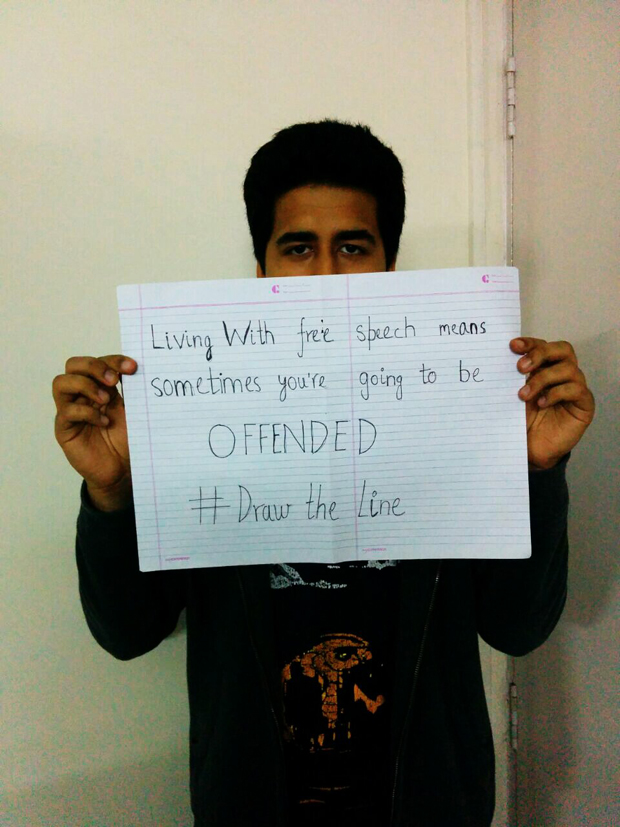

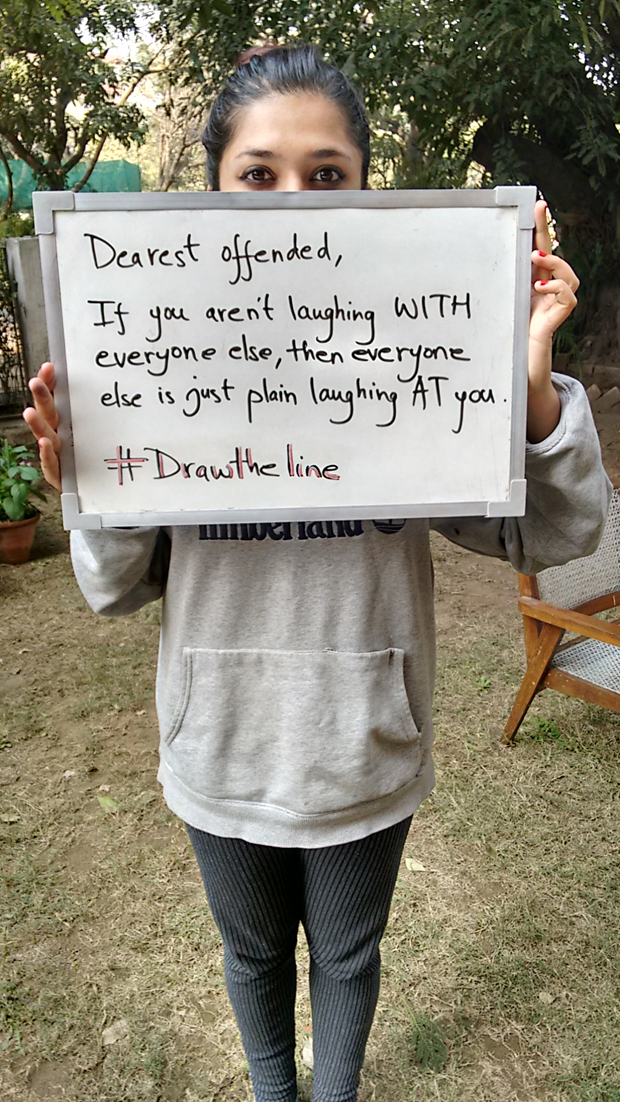

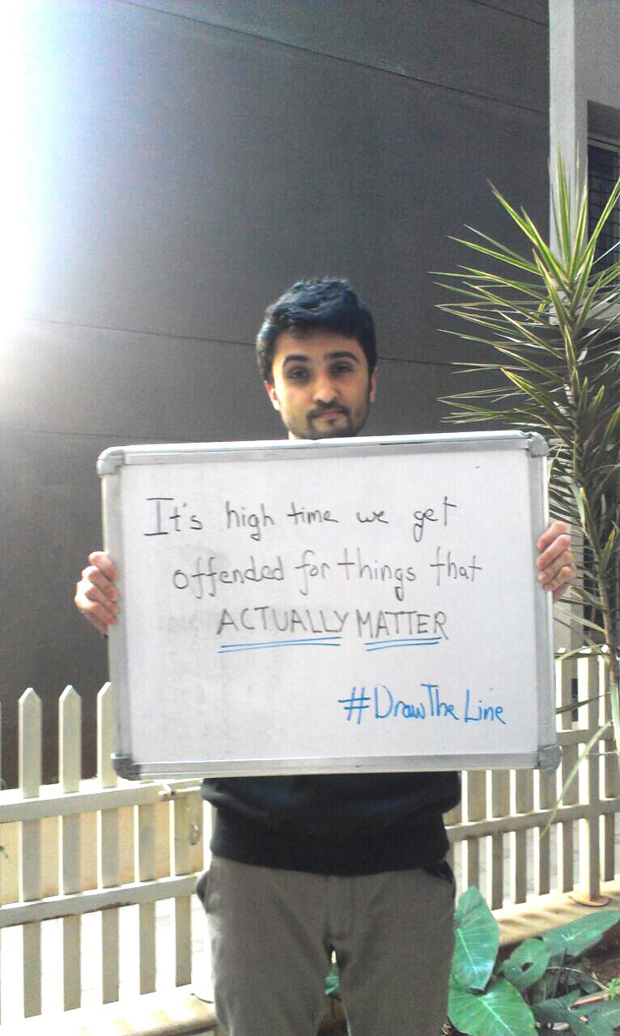

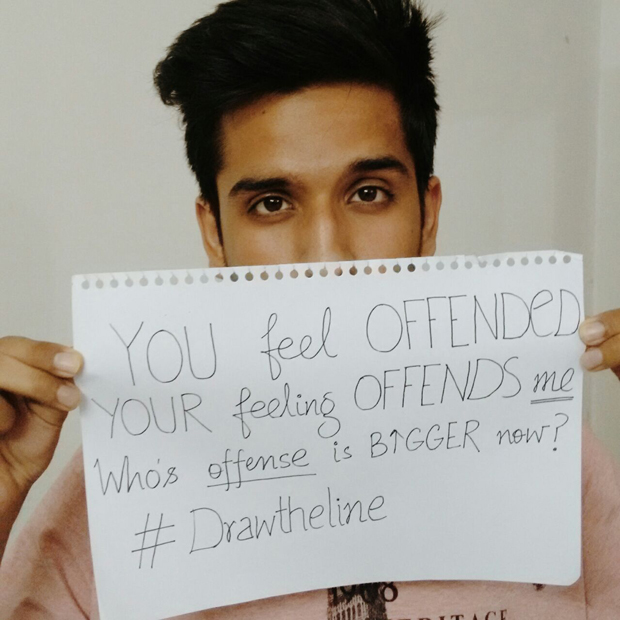

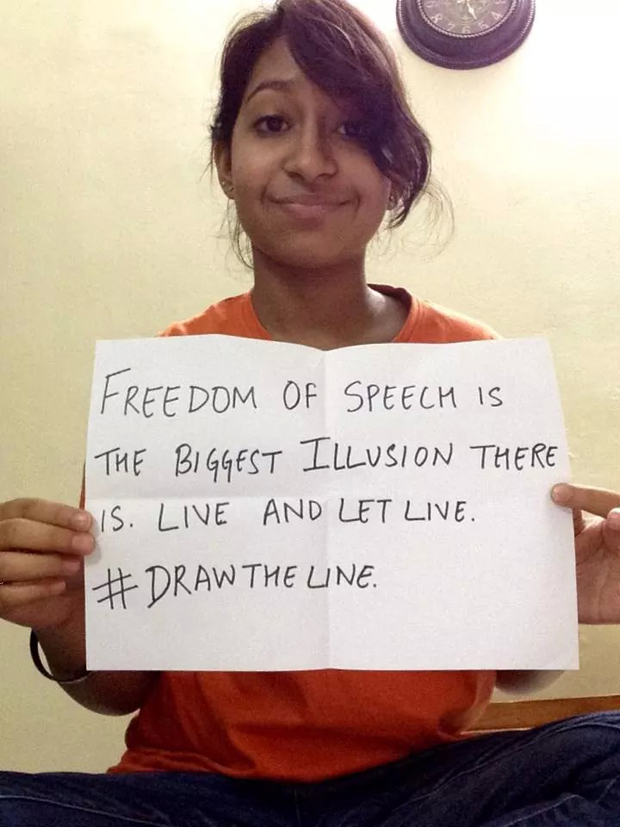

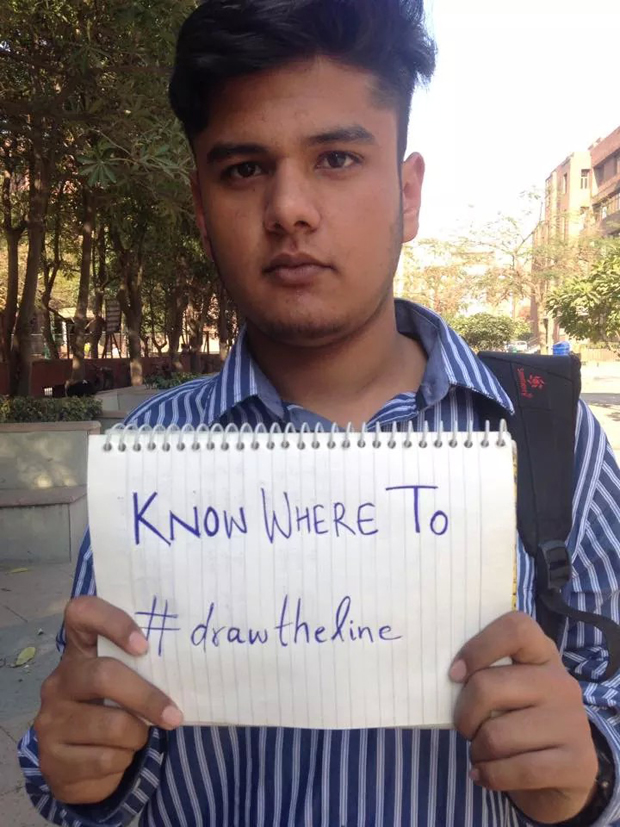

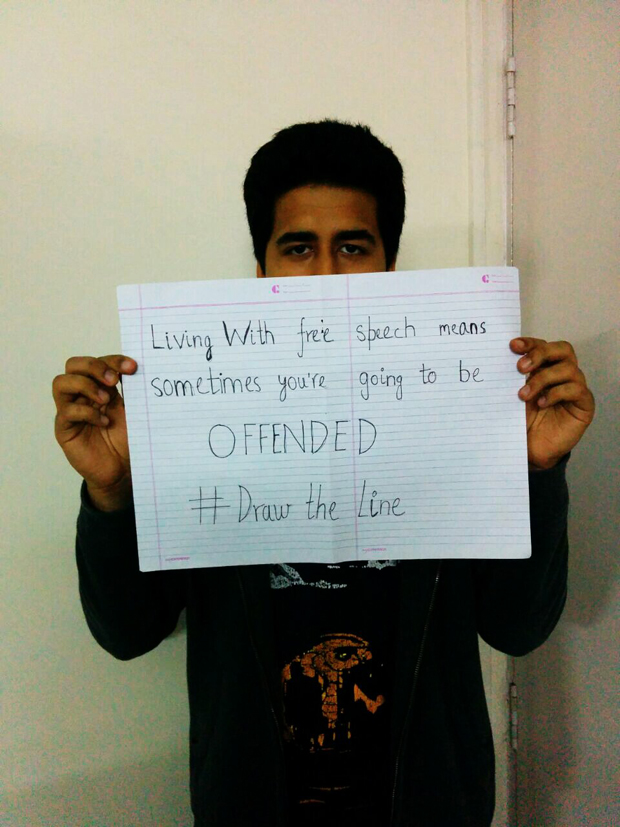

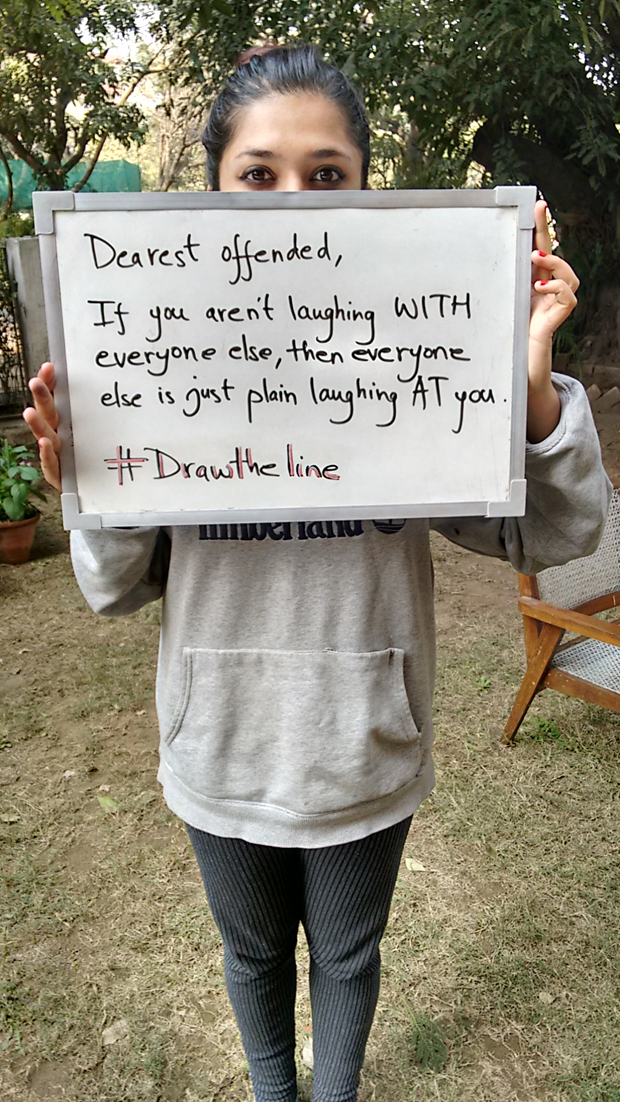

Below, are some young people from across India, who used photographs to join the #IndexDrawtheLine discussion. If you’d like to join the debate, tweet your photos or answers to #IndexDrawtheLine.

This article was posted on 16 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

28 Jan 2015 | Draw the Line, mobile, Youth Board

Censorship, and the degree to which we self-censor, is becoming an increasingly difficult, yet pressing and vitally important, topic of debate amongst an ever-growing international community.

Now, in the internet age, it has never been easier to connect and communicate with so many different people from all across the world. With these wide reaching forms of communication, and various people calling for censorship at different levels, the extent to which offence is considered an acceptable and fundamental part of free speech, has been called into question.

In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo killings, some world leaders have spoken publicly against self-censorship. Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbot urged media in the country to not resort to self-censorship. Some believe that certain groups, communities or organisations should be exempt from satire, criticism or insult. Others might argue that without the right to offend, a proper line of communication can never truly be attained, that no group should be exempt, and that people have the right to offend and be offended, but not to resort to violence and extremism.

This poses the question: is causing offence, and the ability to be offended, a fundamental part of freedom of expression? And, if we remove the right to offend, does this then close down the space for free and open debate?

Tweet your thoughts to #IndexDrawtheLine to get involved in the debate.

This article was published on 28 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Guest Post, News

World leaders march in Paris following the recent attacks in France (Photo: European Council)

Jacob Mchangama is the founder and executive director of Justitia, a Copenhagen-based think tank focusing on human rights and the rule of law. He has written and commented on human rights in international media including Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, The Economist, BBC World, Wall Street Journal Europe, MSNBC, and The Times. He has written and narrated the short documentary film “Collision! Free Speech and Religion”. He tweets @jmchangama

The brutal attack against Charlie Hebdo has seen European leaders rally round the fundamental value of freedom of expression.

French President Francois Hollande led the way by stating: “Today it is the Republic as a whole that has been attacked. The Republic equals freedom of expression.” Prime Minister David Cameron vowed that Britain will “never give up” the values of freedom of speech, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel called the events in Paris “an attack on freedom of expression and the press — a key component of our free democratic culture.” European Union President Donald Tusk stressed that “the European Union stands side by side with France after this terrible act. It is a brutal attack against our fundamental values, against freedom of expression which is a pillar of our democracy.”

This unified commitment to freedom of expression is both admirable and crucial in the aftermath of the killing of cartoonists armed with nothing more than ink, humour and courage. It is also true that freedom of expression is a fundamental European value and that (Western) Europe allows for a much freer debate than most other places in the world. However, European governments and institutions have long compromised this freedom through statements and laws that narrow the limits on permissible speech. Ironically some of these statements and laws target the very kind of offence that Charlie Hebdo excelled in.

Donald Tusk’s principled defence of freedom of expression stands in stark contrast to a 2012 joint statement issued by then EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton, as well as the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League that “condemn[ed] any advocacy of religious hatred … While fully recognising freedom of expression, we believe in the importance of respecting all prophets”. The statement followed the furore over the crude anti-Islamic film “The Innocence of Muslims”, and suggests that mocking prophets is tantamount to religious hatred prohibited under international human rights law and thus exempted from the protection of freedom of expression.

The controversy over The Innocence of Muslims prompted none other than Charlie Hebdo to print its own depictions of Mohammed, including one showing Islam’s prophet naked. That decision drew stern condemnations from the French government. Then Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius remarked that “in the present context, given this absurd video that has been aired, strong emotions have been awakened in many Muslim countries. Is it really sensible or intelligent to pour oil on the fire?”

While Charlie Hebdo has won a number of lawsuits other French figures have been convicted or censored under French law. Last year comedian Dieudonné M’bala M’bala was banned from performing his comedy shows publicly, due to their anti-semitic content. And France is not alone. Swedish shock artist Dan Park was sentenced to six months imprisonment in 2014, over a number of purportedly racist posters deemed “gratuitously offensive” to minority groups by a Swedish court. The owner of the gallery that had displayed the cartoons was also convicted and the posters ordered destroyed.

In 2011, a prominent Austrian Islam-critic was convicted of “denigration of religious beliefs” for stating that the prophet Mohammed “had a thing for little girls”. An elderly Austrian man was found guilty of the same offence for yodelling while his Muslim neighbour was praying. In the United Kingdom, an atheist who left caricatures of the Pope, Mohammed and Jesus in a prayer room in John Lennon Airport was similarly convicted and sentenced to six months imprisonment, though the sentence was suspended. A TV personality’s disparaging social media comments about Scotland and Scots recently prompted Scottish police to tweet that it would “thoroughly investigate any reports of offensive or criminal behaviour online and anyone found to be responsible will be robustly dealt with”.

France and numerous other European countries also have bans against Holocaust denial. In 2010, a Muslim group claiming to expose free speech double standards in the aftermath of the Danish cartoon controversy was convicted after publishing a cartoon suggesting that Jews have made up the Holocaust.

When it comes to countering terrorism, European states increasingly target not only expression that incites terrorism but also expression that may constitute “glorification”. Exactly a week after the attack against Charlie Hebdo, Dieudonné once again ran afoul of the law and was detained over a Facebook post. According to Le Monde at least 50 other cases of terror apology have been opened against people in France since the attack. In Denmark, a number of Islamists have been prosecuted for glorifying terrorism following Facebook postings that seemingly approved of terrorism, including the assault on Charlie Hebdo. Recently British Home Secretary Theresa May unveiled plans that would ban “non-violent extremists” from using television and social media to spread their ideology.

While Europe has a sophisticated and elaborate regional system for the protection of human rights, these institutions have frequently sided with the censors over citizens. In 2008 the EU adopted a framework decision obliging all member states to criminalise certain forms of hate speech. The European Court of Human Rights has found the confiscation of a “blasphemous” film, the conviction of a French cartoonist mocking the victims of 9/11, and the banning of religious fundamentalist group Hizb-ut-Tahrir compatible with freedom of expression. The Council of Europe’s current High Commissioner for Human Rights Nils Muižnieks, has called for all 47 member states to enact bans against Holocaust denial and gender based hate speech.

These non-exhaustive examples demonstrate that contemporary Europe’s approach to freedom of expression is far more complicated and far less principled than the statements made by its leading politicians in recent days suggest. It is an approach to freedom of expression based on the premise that social peace in increasingly multicultural societies requires restrictions on freedom of expression in order to avoid offending ethnic and religious groups. Thus in 2004, when Dutch film maker Theo Van Gogh was murdered by an Islamist offended by Van Gogh’s controversial and anti-Islamic film “Submission”, the Dutch minister of justice proposed to revive the country’s blasphemy law which had been disused since 1968. He argued that “if opinions have a potentially damaging effect on society, the government must act … It is not about religion specifically, but any harmful comments in general.”

Such sentiments might appeal to pragmatists in the wake of the tragedy in France. But there is little reason to think that restricting freedom of expression fosters tolerance and social cohesion across a Europe increasingly divided along ethnic and religious lines, and where anti-semitism and other forms of intolerance is on the rise. In fact such laws seem to fuel the feeling of separateness of modern Europe by legally protecting group identities against offence rather than fostering an identity rooted in common citizenship. While minorities may be offended by disparaging comments, insisting that freedom of expression be limited to protect them from racism and offence, is a very dangerous game at a time where far-right movements with questionable commitment to liberal democracy are on the rise. In this context it should not be forgotten that Dutch politician Geert Wilders once proposed banning the Quran and that the leader of Front National Marine Le Pen wants to ban religious head wear, including the Jewish kippah. The freedoms that (sometimes) allow bigots to bait minorities are also the very freedoms that allow Muslims and Jews to practice their faiths freely. By further eroding these freedoms, no one is more than a political majority away from being the target rather than the beneficiary of laws against hatred and offence. Only by reaffirming a genuine and principled defence of freedom of thought, expression and religion can Europe hope to create a society built on real tolerance and respect for diversity, and where cartoonists neither have to fear gunmen nor jail, but only the moral judgment of their fellow citizens.

This guest post was published on 16 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, France, News

People marched in Paris to show their unity. Photo: European Council President / Flickr

There can be few more insulting coinages than the tedious phrase “moderate Muslim”. What does it mean? Who does it benefit? In the past week, since the atrocities in Paris, we have heard it often: “moderate” Muslims must condemn terrorism. Or, alternatively, the images of Mohammed printed by Charlie Hebdo (and others in solidarity) were alienating “moderate Muslims”: “free speech fundamentalists” must reach accommodation with “moderate Muslims”.

The suggested dichotomy — that one cannot believe in free speech and in Allah, is a dangerous one. More dangerous still is the underlying implication that the “moderate Muslim” is less of a believer than the Muslims who murder, supposedly in the name of God.

It is now eight days since a murderous gang set about killing cartoonists because they had blasphemed and Jews because they were Jews. The gang was composed of men who were Muslims (it is disingenuous, as British Culture Secretary Sajid Javid pointed out, to suggest that these people were not really motivated by Islam, unless you are willing to put yourself forward as the ultimate authority on what is and isn’t Islamic).

Since then, we have gone from revulsion at the acts of the killers to an obsessive focus on the actions of their victims (or at least their victims at Charlie Hebdo: there is relatively little discussion of the slain shoppers in the kosher supermarket).

The function of all this, unwittingly perhaps, is to reinforce a power dynamic. This is about “us” and what “we” did to “them”. “Us”, roughly, being liberal democracy: “them” being European Muslims who somehow, “we” have decided, are something outside.

Worse, we have decided that there is a continuum of “Muslim anger”, at the end of which is inevitable violence. This is to imagine a homogenous bloc of believers, and to ignore the sectarian and political struggles that exist within Islam. By ignoring these struggles, we in fact junk normal Muslims (enough of the “moderate”) in with those for whom the faith is a political project and even an imperial war with the intention of “restoring the Caliphate”.

Meanwhile, “we” have the comfort of decrying our own hypocrisy.

Crying “hypocrite” is enjoyable; indeed, it’s an essential part of how the British press, and British political and social advocacy, works. Beloved satirical institutions thrive on pointing out double standards.

But tempting though this tack is, it is not an argument in itself: yes, the French state is hypocritical on free speech, lauding Charlie while arresting racist comedian Dieudonné for a Facebook post, and announcing a “crackdown” on hate speech. Of course it is rich for world leaders to march for “free speech” when practically every single government you can think of has mechanisms for censoring its citizens in one way or another. But then what? Does that somehow mitigate the horror? Does that mean we shouldn’t stand for free speech? Does that mean, even, that censorship is OK because everyone does a little bit of it?

What is achieved by this is a focus back on our own ability to control things that seem beyond us. These attacks will stop, we imagine, when we find a way to avert them. The murderous ideology motivating these attacks was created by “us”, through, say, “our” support for the 80s jihad against the Soviet occupation in Afghanistan (as Christopher Hitchens pointed out in his 2001 article Against Rationalisation, it was the CIA that “first connected the unstoppable Stinger missile to the infallible Koran”).

But the fact our governments did some things in the past that have come back to haunt us is, again, not a reason for inactivity or passivity on our own parts now. Rather we must deal with what is in front of us, while hoping not to make mistakes that will come back to us.

It is a good and honourable thing that so many people’s instinct, when confronted with aggression, is conciliation. But loathe though my conciliatory soul is to admit it, there is nothing I can concede that will appease the ideology that led to the carnage in France. To quote Hitchens once more, what the murderers and their co-thinkers hate are the parts of liberal democracy that are worth defending: “its emancipated women, its scientific inquiry, its separation of religion from the state.”

None of these things are perfectly achieved in any society, but they should be clung to as aspirations, and defended when needs be. Moreover, they must be maintained as universal, emancipatory values. To portion them off, or worse, to present them as a weapon of one part of society against another — “free speech fundamentalists” versus “moderate Muslims”, is to give succour to those whose only perception of a universal ideal is universal subjugation.

This article was posted on 14 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org