19 Sep 2022 | China, News and features

Huang Xueqin (left) and Wang Jianbing (right)

Today, 19 September 2022, marks one year in detention for two young Chinese human rights defenders: Huang Xueqin, an independent journalist and key actor in China’s #MeToo movement, and Wang Jianbing, a labour rights advocate.[1]

We, the undersigned civil society groups, call on Chinese authorities to respect and protect their rights in detention, including access to legal counsel, unfettered communication with family members, their right to health and their right to bodily autonomy. We emphasise that their detention is arbitrary, and we call for their release and for authorities to allow them to carry out their work and make important contributions to social justice.

Who are they?

In the 2010s, Huang Xueqin worked as a journalist for mainstream media in China. During that time, she covered stories on public interest matters, women’s rights, corruption scandals, industrial pollution, and issues faced by socially-marginalized groups. She later supported victims and survivors of sexual harassment and gender-based violence who spoke out as part of the #MeToo movement in China. On 17 October 2019, she was stopped by police in Guangzhou and criminally detained in RSDL for three months – for posting online an article about Hong Kong’s anti-extradition movement.

Wang Jianbing followed a different path, but his story – like Huang’s – demonstrates the commitment of young people in China to giving back to their communities. He worked in the non-profit sector for more than 16 years, on issues ranging from education to disability to youth to labour. Since 2018, he has supported victims of occupational disease to increase their visibility and to access social services and legal aid.

Arbitrary and incommunicado detention

On 19 September 2021, the two human rights defenders were taken by Guangzhou police; after 37 days, they were formally arrested on charges of ‘inciting subversion of state power’. Using Covid-19 prevention measures as an excuse, they were held for five months in solitary confinement, and subject to secret interrogation, in conditions similar to those of ‘residential surveillance in a designated location’, or RSDL. After months of delays and no due process guarantees, their case was transferred to court for the first time in early August 2022.

We strongly condemn the lengthy detentions of Huang and Wang. In a Communication sent to the Chinese government in February 2022, six UN independent experts – including the Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders and the Working Group on arbitrary detention (WGAD) – raised serious concerns about Wang’s disappearance and deprivation of liberty. They asserted that Wang’s activities were protected and legal, and that Chinese authorities used a broad definition of ‘endangering national security’ that runs counter to international human rights law.

In May 2022, the WGAD went one step further, formally declaring Wang’s detention to be ‘arbitrary’ and urging authorities to ensure his immediate release and access to remedy. Noting other, similar Chinese cases, the WGAD also requested Chinese authorities to undertake a comprehensive independent investigation into the case, taking measures to hold those responsible for rights violations accountable.

We echo their call: Chinese authorities should respect this UN finding, and immediately release Huang Xueqin and Wang Jianbing.

Risks of torture and poor health

In addition to the lack of legal grounds for their detention, we are also worried about conditions of detention for Wang and Huang. Using ‘Covid-19 isolation’ as an excuse, Wang was held incommunicado, during which he was subject to physical and mental violence and abuse. His physical health deteriorated, in part due to an irregular diet and inadequate nutrition, while he also suffered physical and mental torment and depression. UN and legal experts have found similar risks, possibly amounting to torture and cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment, in other Chinese detention practices – including RSDL. According to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the ‘Mandela Rules’), prolonged solitary confinement – solitary confinement lasting more than 15 days – should be prohibited as it may constitute torture or ill-treatment.

Even more concerning are detention conditions for Huang Xueqin, because during the year she has been deprived of her liberty – again, without formal access to a lawyer or communication with her family – no one, including a legal counsel of her choosing, has received formal notification of her situation. We are deeply worried about her physical and mental health, and reiterate that incommunicado detention is a grave violation of international law.

Lack of fair trial guarantees

Given the circumstances, many brave Chinese lawyers may have stepped up to defend Huang Xueqin. But we are alarmed that Huang has been prevented from appointing a lawyer of her choice. In March 2022, her family stepped in, appointing a lawyer on her behalf; she was not allowed to meet her client or see the case file. Nonetheless, that lawyer was dismissed – according to authorities, with Huang’s approval – after just two weeks. The right to legal counsel of one’s choosing is not only a core international human rights standard, but a right guaranteed by the Criminal Law of the PRC.

Chilling effect on rights defence

As is too often the case in China, the authorities’ ‘investigation’ into Huang’s and Wang’s case has had concrete impacts on civil society writ large. Around 70 friends and acquaintances of the two defenders, from across the country, have been summoned by the Guangzhou police and/or local authorities. Many of them were interrogated for up to 24 hours – some for several times – and forced to turn over their electronic devices. The police also coerced and threatened some individuals to sign false statements admitting that they had participated in training activities that had the intention of ‘subverting state power’ and that simple social gatherings were in fact political events to encourage criticism of the government. The Chinese government has been repeatedly warned by UN experts that the introduction of evidence stemming from forced or coerced confessions is a violation of international law and that officials engaged in this practice must be sanctioned.

A call for action

One year on, we call on the Chinese authorities to respect human rights standards, and uphold their international obligations, in the cases of Huang Xueqin and Wang Jianbing. Until Chinese authorities implement UN recommendations and Huang and Wang are released, the relevant officials should:

- Ensure that Huang and Wang can freely access legal counsel of their own choosing, and protect the rights of lawyers to defend their clients.

- Remove all barriers to free communication between Huang and Wang and their families and friends, whether in writing or over telephone.

- Provide comprehensive physical and mental health services to Huang and Wang, including consensual examinations by an independent medical professional, and share the findings with lawyers and family members, or others on request.

- Guarantee that Huang and Wang are not subjected to solitary confinement or other forms of torture or cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment, and that the conditions of their detention comply with international human rights standards.

- Cease actions that aim to intimidate and silence members of civil society from engaging in advocacy for the protection of rights, and ensure that no evidence from coerced confessions is permissible in Huang’s and Wang’s – or anyone else’s – court proceedings.

Signed:

ACAT-France

Amnesty International

Center for Reproductive Rights

Center for Women’s Global Leadership, Rutgers University

Changsha Funeng

China Against the Death Penalty

China Labour Bulletin

CSW (Christian Solidarity Worldwide)

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Frontline Defenders

Hong Kong Outlanders

Hong Kong Outlanders in Taiwan

Human Rights in China

Human Rights Now

Index on Censorship

International Service for Human Rights

Lawyer’s Rights Watch Canada

Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders

NüVoices

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Safeguard Defenders

台灣人權促進會 Taiwan Association for Human Rights

Taiwan Labour Front

The Rights Practice

Uyghur Human Rights Project

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

[1] As their cases are deeply connected, their friends and supporters refer to them as a single case called the ‘Xuebing case’, using a portmanteau of their first names.

16 Sep 2022 | Belarus, Brazil, China, Iran, North Korea, Opinion, Russia, Ruth's blog, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is in a period of national mourning, marking the passing of our head of state, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Global media has been transfixed, reporting on the minutiae of every aspect of the ascension of the new monarch and the commemoration of our former head of state. While the pageantry has been consuming, the constitutional process addictive (yes I am an addict) and the public grief tangible – the traditions and formalities have also highlighted challenges in British and global society – especially with regards to freedom of expression.

We have witnessed people being arrested for protesting against the monarchy. While the protests could be considered distasteful – I certainly think they are – that doesn’t mean that they are illegal and that the police should move against them. Public protest is a legitimate campaigning tool and is protected in British law. As ever, no one has the right not to be offended. And protest is, by its very nature, disruptive, challenging and typically at odds with the status quo. It is therefore all the more important that the right to peacefully protest is protected.

While I was appalled to see the arrests, I have been heartened in recent days at the almost universal condemnation of the actions of the police and the statements of support for freedom of expression and protest in the UK, from across the political system.

What this chapter has confirmed is that democracies, great and small, need to be constantly vigilant against threats to our core human rights which can so easily be undermined. This week our right to freedom of expression and the right to protest was threatened and the immediate response was a universal defence. Something we should cherish and celebrate because it won’t be long before we need to utilise our collective rights to free speech – again.

Which brings me onto the need to protest and what that can look like, even on the bleakest of days. On Monday, the largest state funeral of my lifetime is being held in London. Over 2,000 dignitaries are expected to attend the funeral of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, in Westminster Abbey. The heads of state of Russia, Belarus, Afghanistan, Syria, Venezuela and Myanmar were not invited given current diplomatic “tensions”. While I completely welcome their exclusion from the global club of acceptability, it does highlight who was deemed acceptable to invite.

Representatives from China, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, North Korea and Sri Lanka will all be in attendance, all of whom have shown a complete disregard for some of the core human rights that so many of us hold dear. Can you imagine the conversation between Bolsonaro and Erdogan? Or the ambassador to Iran and the vice president of China?

While I truly believe that no one should picket a funeral – the very idea is abhorrent to me – that doesn’t mean that there are no other ways of protesting against the actions of repressive regimes and their leadership, who will be in the UK in the coming days. In fact the British Parliament has shown us the way – by banning representatives of the Chinese Communist Party from attending the lying in state of Her Majesty – as a protest at the sanctions currently imposed on British parliamentarians for their exposure of the acts of genocide happening against the Uyghur population in Xinjiang province. This was absolutely the right thing to do and I applaud the Speaker of the House of Commons, Rt Hon Lindsay Hoyle MP, for taking such a stance.

Effective protest needs to be imaginative, relevant and take people with you – highlighting the core values that we share and why others are a threat to them. It can be private or public. It can tell a story or mark a moment. But ultimately successful protests can lead to real change. Even if it takes decades. Which is why we will defend, cherish and promote the right to protest and the right to freedom of expression in every corner of the planet, as a real vehicle for delivering progressive change.

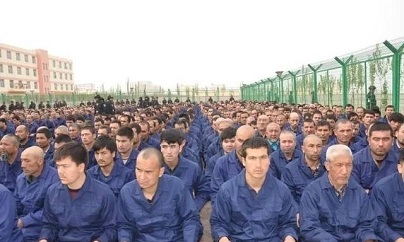

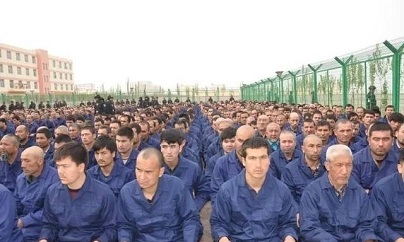

2 Sep 2022 | BannedByBeijing, China, News and features

Detainees at a re-education camp in Xinjiang. Photo WeChat/Xinjiang Juridical Administration

“Serious human rights violations” have been committed in Xinjiang and the arbitrary and discriminatory detention of Uyghurs “may constitute…crimes against humanity” according to a controversial UN report that the Chinese government has been trying to quash.

The report also concludes that allegations of patterns of torture or ill-treatment, including forced medical treatment and adverse conditions of detention, as well as allegations of individual incidents of sexual and gender-based violence are “credible”.

What is also abundantly clear is that the report does not make mention of the word “genocide”, something that has left many campaigners unsatisfied.

The UN report goes so far as to push any mention of “suspicious deaths” occurring inside Xinjiang’s re-education centres into a footnote, saying that despite being presented with allegations on these by interviewees it had “not been possible to verify [them] to the requisite standard”. Restricting the ability of the UN to verify claims of human rights abuses is an effective method by which states, such as China, can effectively game the UN’s investigative process. By ensuring the body cannot access the evidence it needs, China can ostensibly shape what the UN can say without exerting any overt control or interference.

Last month it was revealed that the Chinese mission to the UN was lobbying to prevent the release of the report into human rights abuses in Xinjiang. The publication of the report, first commissioned in 2018, had been repeatedly delayed after having been completed in September 2021. Under tremendous pressure from other UN member states, the report was finally made available on 31 August in the last minutes of UN High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet’s term.

The release of the report has not been welcomed by the Chinese government. In its response to its publication, China’s mission to the UN said: “Based on the disinformation and lies fabricated by anti-China forces and out of presumption of guilt, the so-called ‘assessment’ distorts China’s laws and policies, wantonly smears and slanders China, and interferes in China’s internal affairs”.

The attempt to block the report’s publication may come as a shock to some but this incident is only the most recent attempt by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to silence Uyghurs both within and outside China and to discredit those who try to shine a light on their treatment. In the past, the UN has abdicated from its duty to challenge this global campaign against the Uyghurs. The publication of the report is a notable improvement on the UN’s poor track record. But the controversy surrounding the report’s release has left few critics of the UN optimistic about the ability of the organisation to defend Uyghurs in the future.

Michelle Bachelet meets Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2014, photo: Gobierno de Chile

The release of the Xinjiang report reflects a significant departure from the UN’s traditional soft-touch approach to managing its relationship with China. For example, earlier in 2022 Michelle Bachelet became the first UN High Commissioner to visit China in 17 years. While Bachelet praised China’s progress in labour standards and gender rights, she mentioned only in passing the treatment of Uyghurs, which according to credible reports, includes mass enslavement and systemic rape. Bachelet later admitted that her access to Uyghurs was severely restricted, ostensibly because of COVID-19 regulations, but to many her relative silence appeared to validate the Chinese government’s narrative surrounding events in Xinjiang. After her visit, The Global Times, a Chinese newspaper known for inevitably toeing the government line, ran an opinion piece praising Bachelet for changing her perspective on Xinjiang. The piece celebrated Bachelet’s adoption of CCP terminology – highlighting her use of “the term ‘Vocational Education and Training Centre’ instead of the so-called ‘re-education camp’” – and attributed her much-publicised decision not to run for a second term as High Commissioner to pressure she faced after speaking out in favour of China’s counter-terrorism measures.

Bachelet appeared to accept at face value claims that the re-education camps had “been dismantled” and appeared overly optimistic about “China’s stated aim of ensuring quality developed closely linked to developing the rule of law and respect for human rights”. While she expressed some half-hearted concern about the “lack of judicial oversight” in Xinjiang and mentioned Uyghurs she had met before her trip to China who had lost contact with their relatives, her condemnation of the treatment and mass detention of Uyghurs across the region was decidedly muted. Instead she praised China’s “tremendous achievements” in labour and gender rights, an insult to the victims of slave labour and sexual abuse in the camps. She concluded that “there is important work being done to advance gender equality, the rights of LGBTQI people or people with disabilities and all the people among other [groups]”.

China’s mission to the UN now says that the content of the report “is “entirely contradictory to the formal statement issued by [Bachelet]” following her visit. Just like the Global Times, China’s mission is falsely pointing to Bachelet’s Xinjiang trip as an exoneration of the CCP.

Bachelet herself emphasised that her visit “was not an investigation”, which begs the question why it happened in the first place. All her soft touch approach achieved was to grant the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) a significant PR win.

UN whistleblower Emma Reilly

To understand why UN officials like Bachelet have traditionally been so cautious about criticising China, Index spoke to Emma Reilly (left), an Irish former human rights officer at the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Reilly was fired in 2021 after blowing the whistle in 2017, revealing how the UN had for years been passing the names of Uyghurs set to testify before the UN to the Chinese government. Reilly explained to Index that Eric Tistounet from the OHCHR told concerned staff that “not giving them over would further Chinese distrust of the UN”.

One of the names on the list was Dolkun Isa who now resides in Germany. After the UN passed over his name to the Chinese authorities, his remaining family members who still resided in Xinjiang received a visit from the police. His parents later died in a re-education camp in circumstances that are still unclear. Reilly told Index that another person the UN exposed without their knowledge died upon their return to Xinjiang.

After the UN issued a medical report about Reilly, the Swiss police visited Reilly’s house and prevented her from attending a meeting about the issue she had exposed. In doing so, the UN effectively transformed the Swiss police into a tool of CCP censorship.

A tribunal was initiated to investigate Reilly’s case with the assistance of Rowan Downing QC, a former President of the UN Dispute Tribunal and an international war crimes judge. When it became clear that Downing’s ruling would not be favourable towards the UN, he was removed from his position. Downing compared this move to a coup.

Reilly told Index that the UN’s general reluctance to criticise the CCP is based on the misguided assumption that significant concessions need to be made to maintain a friendly relationship with the Chinese government. According to Reilly, it is commonly believed at the UN that increased engagement with the Chinese government will lead it to internalise global norms of human rights. But the opposite appears to be the case. In fact, the Chinese government has proven itself to be a powerful norm maker of its own as it becomes increasingly assertive in the UN.

Rosemary Foot’s book “China, the UN and Human Protection” seeks to explain the paradox of a China that is significantly more prominent in the UN system yet increasingly resistant to many of its central tenets. Most significantly, the Chinese government has sought to bolster the importance of sovereignty and undermine the universal nature of human rights.

For example, China had only used its security council veto power six times before the outbreak of the Syrian civil war. It then used it seven times to block resolutions condemning the Assad regime. The Chinese government believes that the treatment of Syrians, Uyghurs and other groups should be treated as “internal affairs” and economic growth should be seen as the principal means of improving human rights. As Kenneth Roth, the former executive director of Human Rights Watch, recently wrote, “if Beijing had its way, human rights would be reduced to a measurement of growth in gross domestic product”.

In her discussion with Index, Reilly expressed dismay that her case had received the most attention from right-leaning outlets sceptical of the UN project. Other outlets tended to focus on the treatment of whistleblowers rather than the behaviour she was uncovering and the necessity of systemic reform. Like many other UN whistleblowers, Reilly remains committed to the UN project and wants it changed, not abandoned.

Disempowering the UN (like the Trump administration tried to do by making significant cuts after its recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel was rejected) will only empower the Chinese government to fill the vacuum. But the typical relationship the UN has had with the Chinese government swings the pendulum too far in the opposite direction. The UN must not allow itself to become a tool for China to censor its opponents but starving the UN of funds, undermining its mandate, and expecting it to reform is not a tenable solution that protects universal rights and targeted groups, including Uyghurs both in China and elsewhere.

Given the UN’s poor track record of endangering critics of the CCP, does the release of the Xinjiang report suggest the arrival of the kind of systemic reform that Reilly and others have called for?

Critics are sceptical that this recent development (while welcome) reflects a newly assertive United Nations. The next step would be for an independent investigation to be conducted into events in Xinjiang. Calls for such an investigation have also come from within the UN system after 50 UN human rights experts urged the Human Rights Council in 2020 to establish an independent UN mandate to monitor and report on human rights violations in China. According to the OHCHR’s own statement on this recommendation “unlike over 120 States, the Government of China has not issued a standing invitation to UN independent experts to conduct official visits.” However, two years later and progress has been glacial. Considering that the release of a report took almost three years once it was completed and was only possible after overwhelming pressure from other member states, any next step looks like an insurmountable challenge requiring consistent international solidarity and pressure at a time of growing international tension. The Chinese government cannot exert total influence over the UN to silence all of its critics but as demonstrated by the delays of the Xinjiang report, the UN process remains too easy for human rights abusers to impede.

Reilly remains critical of the UN. Now that the UN has officially recognised in its report that the CCP carries out “reprisals against Uyghur and other predominately Muslim minorities abroad in connection with their advocacy, and their family members in [Xinjiang]”, their continued smear campaign against her and refusal to condemn the policy she exposed is an increasingly untenable position.

There is also the question of how permanent the UN’s apparent change of strategy will be. It is notable that Bachelet only felt capable of releasing the report upon her departure from office when she would not have to face the consequences of her decision. Perhaps that now Bachelet is gone, her brief experiment with explicitly calling out the CCP’s human rights abuses will be replaced with business as usual.

Meanwhile, the global campaign to target Uyghurs both within and outside China continues

. Earlier this year, Index published a landmark report examining how the CCP has externalised its censorship and intimidation of Uyghurs even to those who have managed to escape to Europe in search of freedom and security. As highlighted by Reilly’s brave decision to blow the whistle, the CCP will use every mechanism and lever at its disposal to enforce its propaganda and target its perceived adversaries. Even though they now reside in Europe, Uyghurs continue to receive threats as do their families still living in Xinjiang. This report highlighted the lengths the CCP would go to strengthen its narrative and censor those brave enough to speak out, irrespective of where they are. It also revealed the inadequate response of European states to respond to this threat. Without a robust response, the CCP is emboldened to continue exporting its message to other countries and through international bodies like the UN. If the UN has only just reached the stage of officially recognising that this years long campaign is actually taking place, let alone taking active measures to stop it, who can Uyghurs rely on?

[Index made repeated requests to the United Nations for comment on this article but no replies were received at time of publication.]

To learn more about the censorship of Uyghurs in Europe, read Index’s Banned by Beijing report “China’s Long Arm”: https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2022/02/landmark-report-shines-light-on-chinese-long-arm-repression-of-ex-pat-uyghurs/

1 Jul 2022 | China, Hong Kong, News and features

Mark Clifford, Kris Cheng and Benedict Rogers speak in parliament ahead of the 25th anniversary of the handover of Hong Kong

“The fear of possibly being attacked by the far-reaching Chinese Communist Party is always there.” These were the words of political activist Nathan Law. His background in peaceful activism and outspoken pro-democratic views have made him a target of the Chinese Communist Party.

Law, who is best known as one of the student leaders of the Umbrella Movement and who was the youngest legislator in Hong Kong history, fled Hong Kong in 2020, a few days before the implementation of the National Security Law (NSL). In the same year, Law was listed as one of the 100 most influential individuals in the world by Time Magazine.

Law was speaking at an event organised by Index on Censorship and The Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong inside parliament, the heart of British politics. The purpose? To highlight the actions of the Chinese government and showcase the fearmongering tactics used to manipulate and intimidate all Hong Kongers, both domestic residents and those abroad, ahead of the 25th anniversary handover of Hong Kong from British rule to Beijing rule.

The event was chaired by Index on Censorship’s Jemimah Steinfeld and hosted by Neil Coyle, a Member of Parliament. Other panellists included Mark Clifford, former editor-in-chief for both The Standard and The South China Morning Post as well as president of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong, Evan Fowler, a writer and researcher from Hong Kong, Benedict Rogers, the CEO of Hong Kong Watch, and Kris Cheng, a journalist who used to work at Hong Kong Free Press.

Coyle kicked it off by setting the tone of the evening’s conversation: “What we [are] discussing and hearing today in this building would guarantee the panellists’ arrests and imprisonments were they to say the same in Hong Kong today.”

The implementation of the NSL has placed a stranglehold on dissent. While the punishment for violating the law is clear — up to life in prison for some “offences”— how the Chinese government interprets and manipulates the law falls into a grey zone, leaving many Hong Kong residents in a perpetual state of fear.

The NSL was a turning point, though Clifford said that “Hong Kong was always living on borrowed time”. But he spoke of how pre-handover it wasn’t always obvious the direction China would take, as the last governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, had created a much more pluralistic society. Speaking of this period, Clifford said that “the Chinese rightly understood that once Hong Kong people tasted freedom and democracy, it was going to be hard to put the genie back in the bottle.”

Rogers also spoke of a time where there was still hope. “For the five years that I lived and worked in Hong Kong, those first five years after the handover, that sense of foreboding when I got there appeared to have largely receded. There was a sense that One country, Two systems, by and large, was working pretty well. Hong Kong felt pretty free.”

By the time Rogers left in 2002, however, he started to see the subtle warning signs turn increasingly more substantial. “I saw some worrying signs that made me decide after five years it was time for me to move on.”

Fowler recalled the days surrounding the Handover. “It’s now being celebrated as this great event where Hong Kong was returned to the Motherland, where all the comrades happily embraced returning to the Communist fold. I really didn’t feel that at all. The feeling that I remember was that people didn’t know what was going to happen. Taking what [Clifford] said earlier about the old colonial saying ‘borrowed place on borrowed time,’ there really was a sense of that.”

Fowler went on to share an analysis of two different eras in history. “I suppose the big transition was before 1997. No matter how things were going in Hong Kong, there was always this feeling that you didn’t know what future lay in store, and ultimately you knew that that future wasn’t to be decided by you.”

Post-1997, Fowler said the general consensus was that people believed most issues had been resolved, but that it certainly wasn’t a wonderful celebration every time. Today though the CCP is trying hard to erase any memories of protest and misgivings from the time, as we recently reported here.

Chinese propaganda is something panellist Cheng was accustomed to throughout his childhood in Hong Kong. At school, Cheng went on a “national education tour” in Beijing. Cheng said the tour was a way to influence the minds of younger generations. “The whole thing is to let you have the experience in the Chinese government and capital, to know what was going on in China, to build that identity. I called it ‘softcore propaganda.’”

Cheng used this experience as motivation for his career as editorial director at Hong Kong Free Press. It also made Cheng realise the dissimilarities between Hong Kong and China. “I don’t think, at the time, that there was some sort of Hong Kong identity in the Hong Kong people, but it actually made me feel like ‘Wait, we [Hong Kongers] are a bit different.’”

Themes of oppression and manipulation were hit on heavily throughout the event. Law argued that the “fight of Hong Kong is not only for Hong Kong people”. He believes that the democratic nations of the world must “stand at the forefront of the global resistance and pushback against the rise of authoritarianism. At the end of the day, if we cannot contain the aggression of the Chinese Communist Party, there will be no ability to make a change in Hong Kong.”

“If the case of Hong Kong can remind us how fragile freedoms and democracy are and how underprepared we have been for the past few decades, then it can remind everyone we need resources and [need] to form global alliances to heckle these dictators’ aggression,” said Law.

He urged individuals on the panel and those within the room to “not let the government forget the atrocities committed against protesters and pro-democracy movements, at least until we have gathered enough mechanisms to hold these human rights perpetrators accountable.”

You can listen to a recording of our Hong Kong event here.