28 Apr 2021 | Africa, Burma, China, Hong Kong, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Slapps, United States, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021 extras

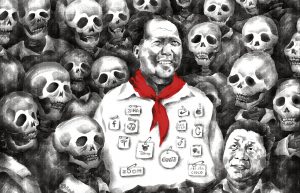

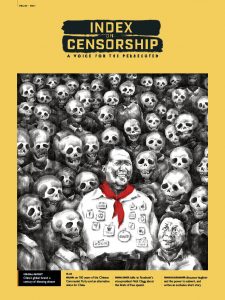

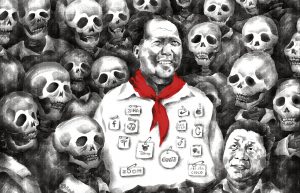

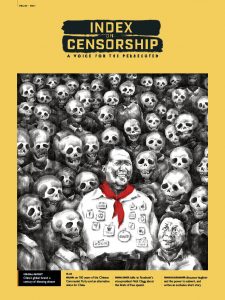

Illustration: Badiucao

Index looks back on 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and how their censorship laws continue to shape the lives of people around the world and threaten their right to free speech. Inside this edition are articles by exiled writer Ma Jian and an interview with Facebook’s vice-president for global affairs, former UK deputy Prime minister Nick Clegg; as well as an exclusive short story from acclaimed writer Shalom Auslander.

Acting editor Martin Bright said: “I am delighted to introduce the latest edition of Index which marks the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party.”

“This year also marks the 50th anniversary of the magazine and I am proud that we are continuing the founders’ legacy of opposition to totalitarianism.”

“In this Spring edition of Index we are particularly pleased to publish an exclusive essay by the celebrated Chinese writer Ma Jian, who suggests that an alternative tradition of tolerance and freedom is still possible.”

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

The Index: Free expression round the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern

Fighting back against the menace of Slapps by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Governments continue to threaten journalists with vexatious law suits to stop critical reporting

Friendless Facebook by Sarah Sands: An interview with Facebook vice-president Nick Clegg about being a British liberal at the heart of the US tech giant

Standing up to a global giant by Steven Donziger: A lawyer who has gone head to head with the oil industry since 1993 at great personal cost tells his story

Fear and loathing in Belarus by Yahuen Merkis and Larysa Shchryakova: The crackdown on journalism has continued with arrests. Read the testimony of two reporters

Killed by the truth by Bilal Ahmad Pandow: Babar Qadri was one of Kashmir’s most strident voices, until he was gunned down in his garden

Cartoon by Ben Jennings: Arguments about the removal of statues cause a stir

The martial art of free speech by Ari Deller and Laura Janner-Klausner: The question of Cancel Culture continues to rage. Is it really a problem?

Ma Jian

Burning through censorship: Censorship-busting online organisation GreatFire celebrates its 10th anniversary

The party is your idol by Tianyu M. Fang: China’s propaganda is adapting to target young people

Past imperfect by Rachael Jolley: Four historians explain how the CCP shaped China and ask if globalisation will be its undoing

Turkey changes its tune by Kaya Genç: Uighur refugees living in Turkey find themselves victims of a change in foreign policy

The human face and the boot by Ma Jian: The acclaimed writer-in-exile reflects on 100 years of the CCP and its legacy of bloodshed

A moral hazard by Sally Gimson: Universities around the world and the CCP’s challenges to academic freedom

Director’s cuts by Chris Yeung: Hong Kong broadcaster RTHK has been squeezed by China’s tightening control

Beijing buys Africa’s silence by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Africa’s rich natural resources are being hoovered up by China

A new world order by Natasha Joseph: Journalist Azad Essa found when he wrote about China in Africa, his writing was silenced

A most unlikely ally by Stefan Pozzebon: Paraguay has long been an ally of Taiwan, but it’s paying an economic price

China’s artful dissident: A profile of our cover artist: the exiled cartoonist Badiucao.

Lies, damned lies and fake news by Nick Anstead: Fake news is rife, rampant and harmful. And we can only counter it by making sure that the truth is heard

Censorship? Hardly by Clive Priddle: Even the most controversial book usually finds a publisher after it has been turned down

A voice for the persecuted by Ruth Smeeth: As Index celebrates its 50 year anniversary, we note why free speech is still important

Collective ©ALEXANDER NANAU PRODUCTION

Don’t joke about Jesus by Shalom Auslander: An exclusive short story based on a joke by the acclaimed author of Mother for Dinner

Poet who haunts Ukraine by Steve Komarnyckyj: Vasyl Stus, the writer who remains a Ukrainian hero, 35 years after perishing in a Soviet gulag

The freedom of exile by Khaled Alesmael, Leah Cross: A young refugee Syrian writer on the love between Arab men

Forbidden love songs by Benjamin Lynch: Iran’s underground pop music scene upsets the regime

Reviews: Saudi Arabia’s murder of Jamal Khashoggi, USA Gymnastics and healthcare in Romania: we review three new documentaries

War of the airwaves by Ian Burrell: The Chinese government faces difficulties with its propaganda network CGTN

28 Apr 2021 | China, Magazine, News and features, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116639″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Sometimes, from the most trivial event or seemingly insignificant interaction, you can gauge the health of a society and decide: “This is a place I’d like to live, a place conducive to happiness.”

A few years ago, while in Taiwan for a literary festival, I went to a night market to look for tangyuan – the sticky rice dumplings that are traditionally eaten on the final day of Chinese New Year. As their name is a homophone for the word “union”’, Chinese families eat them on this day to ensure that during the coming year they will remain united. As I’d recently been cast into exile from mainland China, I thought the dumplings could assuage my longing for home.

After a long search, I found a small dumpling stall and asked the elderly owner if she had any. She told me she’d sold out, but that if I bought a bag of frozen ones from the supermarket across the road she would boil them up for me on her stove. I did as she suggested and she served them to me in a big bowl, handed me a spoon and invited me to sit at one of her rickety tables. She fervently refused my offer of payment. As I sat there savouring the hot, translucent dumplings stuffed with sweet black sesame paste, I felt closer to home than I had done in years.

It was not the dumplings themselves or the memories they evoked that made me feel close to home. It was the simple act of kindness from this old woman who didn’t know me. Her kindness struck me as peculiarly Chinese. It was imbued with what we call renqing: a sentiment, a human feeling that inspires one person to perform a favour for another simply because they can, with no thought of recompense.

Traditional Chinese society was glued together by such sentiments. Their roots lie in Confucian values of benevolence, righteousness and propriety. At the heart of them all is the idea that to lead a good life you must treat others with compassion, that each human being has the potential to be good and is worthy of dignity and respect. Almost 500 years before the birth of Christ, Confucius devised his own Golden Rule: “When you leave your front gate, treat each stranger as though receiving an honoured guest … Do not do to others what you do not wish for yourself.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd0d0d”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The horror of the current situation in Xinjiang is in a category of its own”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

But in China, these ancient values have been bludgeoned by 70 years of Chinese Communist Party rule. Since the days of Mao, the CCP has clung to power through violence, propaganda and lies, viewing its subjects as senseless cogs that it can blind with promises of a future Utopia while confining them to a present hell. How easy it is for humans to be stripped of reason by a tyrant’s deceit and malice. At 13, having survived the Great Famine caused by Mao’s reckless Great Leap Forward campaign, when my siblings and I had had to eat toothpaste and tree bark to stave off starvation, I nevertheless longed to join Mao’s party. When he launched his Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, I was incensed that the class background of my grandfather, who had perished in a Communist jail, disqualified me from joining Mao’s Red Guards. The deepest hope of my generation was that after purging China of bourgeois elements, we could travel to Britain and the USA to liberate their populations from the yoke of capitalist oppression and welcome them into the CCP’s revolutionary fold.

Slowly, as I witnessed horrific scenes of mob violence, I began to see this march to Utopia for what it was: a dehumanising nightmare that divided people into class categories, pitting one against the other in constant struggle, “rightist” against “leftist”, neighbour against neighbour. Time-honoured values of family loyalty and respect for elders were shattered as sons were encouraged to betray their fathers and daughters their mothers. No thought other than Mao Zedong Thought was allowed. Anyone who, however inadvertently, strayed from party orthodoxy was branded a class enemy and destroyed.

At least 45 million people are estimated to have died in Mao’s Great Famine. Millions more were killed or persecuted in his Cultural Revolution. Mao’s ideas and values caused catastrophic suffering and death, and corroded the hearts of the nation.

In the 40 years since Mao’s death, the Chinese have been forbidden to reflect on their traumatic past or contest any current injustices. Like a cunning and obdurate virus, the CCP has mutated. While other communist regimes around the world have fallen, it lives on, still suppressing free thought, still whitewashing history, but embracing, with increasing vigour, the capitalism Mao strove to eliminate. The party has loosened tethers it itself placed on the economy, and the Chinese have got rich. Although it continues to spout Marxist-Leninist jargon, its overarching obsession is power, and how to cling on to it. It still views the Chinese people as senseless cogs it can manipulate or flatten as it pleases. It still tells them that the material life is all that matters and that happiness is the China Dream of wealth and national glory conceived by the party’s current leader, Xi Jinping. Freedom, democracy, human rights, the desire to become master of one’s own fate: all of these are unnecessary, absurd, dangerous, it says. The Chinese people have no need for them!

In George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston is told that if he wants a picture of the future, he must “imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever”.

This totalitarian nightmare is not some fictional future, though. Published in 1949, the year Mao rose to power, the novel prophetically describes China’s fate under CCP rule.

For moments, sometimes for days or weeks during the dark decades of China’s recent history, a hand has pushed the boot aside and the human face has looked up. It looked up with hope and joy during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, when millions gathered across the nation to call for freedom and democracy. In 2008, it looked up when 303 Chinese dissidents signed Charter 08 that argued for an end to one-party rule and asserted that freedom and human rights are universal values that should be shared by all humankind. In Hong Kong, the human face has looked up defiantly as the territory bravely struggles to retain what few freedoms it has left. And last year, back on the mainland, the face looked up for a few short hours when, after Dr Li Wenliang was reprimanded for raising the alarm about Covid-19 and then died of it, Chinese social media became flooded with the courageous hashtag #IWantFreedomOfSpeech.

Every time citizen journalists like Fang Bin upload independent reports on social media, civil rights activists like Xu Zhiyong call openly for political reform, dissidents like Gao Yu shine a light on the secret workings of the oppressive state, the human face looks up and proclaims: “without freedom of speech we are all enslaved”.

But each time, the CCP boot stamps back down again. In 1989, it sent the tanks to Tiananmen Square to crush the unarmed protesters. In 2009, it imprisoned the leading dissident Liu Xiaobo who co-authored Charter 08, banned him from collecting the Nobel Peace Prize he was awarded the following year, and in 2017, humiliated him even in death by stage-managing his funeral, forcing his family to drop his ashes unceremoniously into the sea. Fang Bin has been disappeared, Xu Zhiyong is in prison, Gao Yu and countless other dissidents like Ding Zilin, who courageously persists in dragging the Tiananmen massacre from state-imposed amnesia, are under intense surveillance. In Hong Kong, the party has violated the Sino-British Joint Declaration, beaten protesters and arrested every prominent critic. In Tibet, decades of CCP oppression have driven 156 Tibetans to set fire to themselves in anguish.

“But look how much richer the Chinese have become!” CCP apologists cry out. “Western democracies like the USA and Britain are a sham, corrupt and incompetent – see how they failed to contain the Covid-19 epidemic! Does this not prove the superiority of China’s authoritarian regime?”

They ignore that the CCP’s obsession with secrecy caused the initial outbreak’s catastrophic spread, and that democratic Taiwan far outperformed China, recording only 10 Covid deaths, without the government having to imprison whistleblowers or weld Covid patients into their homes.

It’s true that UK prime minister Boris Johnson and US president Donald Trump failed disastrously to contain the virus. (Is it a coincidence that both leaders share Xi’s disregard for the truth?)

But Trump could be voted out, Johnson can be vilified in the press, and no one loses their freedom of speech. This is the power of democracy – however embattled it may become, it guarantees, more than any other system yet invented, that every citizen can have their say and that political change is always constitutionally possible.

“The Chinese just aren’t suited to democracy, though – it’s not in their culture,” the apologists retort. But Taiwan destroys this argument – it proves that the Chinese can be both prosperous and free.

“It’s different on the mainland,” the apologists insist. “Look at the popular support for the party!” But the apologists fail to understand that when people have been governed by lies and fear, their gratitude to their leaders is little different from the affection some hostages develop for their captors.

The truth is, everyone in China is a hostage. Some may be wealthier than others, some more aware than others of the prison bars that surround them, but everyone is spiritually incarcerated by the CCP. They have all been denied the most fundamental human right: the right to form independent thought. Without freedom of thought, one loses respect for oneself and the ability to respect and feel compassion for others. China may be rich, but 70 years of CCP rule has plunged the country into an ever-deepening moral abyss.

It is impossible to make a hierarchy of misery, to judge the death and persecution of one person or of one people as worse than those suffered by others. But the horror of the current situation in Xinjiang seems to be in a category of its own. The images of Uighur convicts, handcuffed and blindfolded, heads shaven and bowed, being herded onto trains; of hastily-erected internment camps with watchtowers, barbed wire fencing and high perimeter walls; of inmates forced to smile and sing to foreign inspection teams, despair welling in their eyes; the accounts of torture, rape, forced sterilisations and indoctrination from the few Uighurs who have managed to escape. These images and accounts recall the worst atrocities of the 20th century. In the name of “anti-terrorism”, a people and a culture are being annihilated. Determined to eradicate any perceived threat to its rule, the CCP is stamping its boot down on an entire ethnic group, aiming to extinguish the Uighurs “root and branch”.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd0d0d”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”As I witnessed horrific scenes of mob violence, I began to see this march to Utopia for what it was: a dehumanising nightmare”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Ma Jian

When reports first emerged of the Xinjiang camps, I found the images too dreadful to bear. Wanting to convey my grief and solidarity, I sought out a Xinjiang restaurant in London, which has now closed. After I paid for my meal, I asked the owner to join me outside, so that we could speak without being overheard. I asked him about the camps, and whether he still had family in the province. It turned out he was not a Uighur but a Han Chinese who had moved to Xinjiang in the 1990s. “Those Uighurs – they deserve what’s happened to them!” he said with a smirk. “Good thing they’ve been locked up in the camps. My family say the streets are much quieter now.”

His words were abhorrent, but he was expressing views many Han Chinese on the mainland share. These Chinese mainlanders are not evil, of course. The corrupted moral view that some of them may have is the tragic product of an evil regime.

On the hundredth anniversary of its founding, the CCP will reassert that ‘Without the Communist Party, there is no New China!’ Xi wants his model of authoritarian capitalism to be applauded and replicated by the entire world. He wants the UN to move its headquarters to Beijing – the ultimate validation of his ideas and values.

For anyone who cherishes human rights and freedom of speech it is repugnant that, while hundreds of millions of victims of the CCP’s man-made disasters lie rotting in their graves, while Chinese dissidents continue to be jailed and disappeared, while Hong Kong turns from a place that once offered refuge to mainland dissidents into a place from which its own citizens flee, while Tibetans continue to set themselves on fire, and while a genocide is taking place right now in Xinjiang – it should be repugnant to everyone that in the face of such unending injustice, some Western commentators could suggest that the CCP is winning the battle of values and ideas in the world.

But more appalling still is that for the sake of some grubby trade deals with China, the political leaders of Western democracies are doing little more than offering asylum to Hong Kong citizens and expressing “concern” at China’s human rights abuses. As China’s economy grows and CCP values spread across the nation’s borders, freedom of speech, liberal values and renqing – that essential human capacity for kindness and compassion – will become increasingly endangered. Unless Western leaders defend, not with gunboats or empty rhetoric but with unwavering commitment, the enlightenment values of liberty, fraternity and reason that should form the foundation of every civilised country, then there will soon be very few places left in the world that are conducive to human happiness.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1 Apr 2021 | China, Hong Kong, Media Freedom, Opinion, Ruth's blog, Taiwan

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Photo: PublicDomainPictures

The awful actions of the Chinese government over the last month have dominated our news agenda. The collective actions of the government and their outliers have been designed to silence dissent, to intimidate and to bully.

They have repeatedly attacked core democratic principles both at home and abroad, undermining fair political participation. They’ve arrested democracy activists, changed the law to restrict electoral access to the Hong Kong Legislative Council to sanctioned ‘patriots’ otherwise known as the allies and friends of the Government of China.

The ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has also sanctioned British parliamentarians and activists for daring to speak out about the acts of genocide, happening as I type, in Xinjiang province against the Uighur community. The CCP chose not to target members of the British Government nor key businesses with sanctions.

Instead, it sent a political message and targeted backbench Conservative MPs, two think-tanks and an academic, those who had been most vocal in exposing the actions of the CCP in both Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia. This was a move intended to silence criticism not impose economic sanction, a clumsy and ineffectual effort to restrict free speech outside China’s borders.

This week, these aggressive actions by the CCP culminated with yet another attack on media freedom when the BBC’s lead China correspondent, John Sudworth, was forced to relocate with his family from Beijing to Taiwan after a campaign of state-sanctioned threats and intimidation. Sudworth and his wife, a fellow journalist for the Irish RTE, Yvonne Murray, were faced with no other option than to leave after months of personal attacks in Chinese state media and by Chinese government officials. They will both continue to report on events in China from Taiwan.

The harassment of international journalists in China (and now in Hong Kong) is becoming normalised, with dozens of journalists having to leave in recent months; threats of visas being withheld are now commonplace. This is simply unacceptable.

China seeks to be a loud voice on the global stage – they need to live up to their commitments under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They need to remember they are signatories to Article 19 and that media freedom and free expression are protected rights.

Index stands in solidarity with John and Yvonne.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Mar 2021 | China, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116480″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Last week, the Chinese government outlined sanctions against nine British individuals and three organisations for daring to speak out about what is going on in Xinjiang.

Those affected by the sanctions are former Conservative party leader Iain Duncan Smith, Tom Tugendhat, chair of the foreign affairs select committee, Nus Ghani from the business select committee, Neil O’Brien, head of the Conservative policy board and China Research Group officer, Tim Loughton of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, crossbench peer David Alton, Labour peer Helena Kennedy QC and barrister Geoffrey Nice.

The only individual not from the political sphere is Dr Joanne Smith Finley, Reader in Chinese studies at Newcastle University.

The organisations include the China Research Group, the Conservative Human Rights Commission and Essex Court Chambers.

China made the move after the British government imposed sanctions on four Chinese officials and one organisation last Monday: Zhu Hailun, former secretary of the political and legal affairs committee of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR); Wang Junzheng, deputy secretary of the party committee of XUAR; Wang Mingshan, secretary of the political and legal affairs committee of XUAR; Chen Mingguo, vice chairman of the government of the XUAR, and director of the XUAR public security department; and the Public Security Bureau of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps – a state-run organisation responsible for security and policing in the region.

A statement from Tom Tugendhat and Neil O’Brien on behalf of the China Research Group said, “Ultimately this is just an attempt to distract from the international condemnation of Beijing’s increasingly grave human rights violations against the Uyghurs. This is a response to the coordinated sanctions agreed by democratic nations on those responsible for human rights abuses in Xinjiang. This is the first time Beijing has targeted elected politicians in the UK with sanctions and shows they are increasingly pushing boundaries.

“It is tempting to laugh off this measure as a diplomatic tantrum. But in reality it is profoundly sinister and just serves as a clear demonstration of many of the concerns we have been raising about the direction of China under Xi Jinping.”

Commenting on China’s decision, foreign secretary Dominic Raab said: “It speaks volumes that, while the UK joins the international community in sanctioning those responsible for human rights abuses, the Chinese government sanctions its critics. If Beijing want to credibly rebut claims of human rights abuses in Xinjiang, it should allow the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights full access to verify the truth.”

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said, “The MPs and other British citizens sanctioned by China today are performing a vital role shining a light on the gross human rights violations being perpetrated against Uyghur Muslims. Freedom to speak out in opposition to abuse is fundamental and I stand firmly with them.”

Newcastle University academic Dr Joanne Smith Finley believes she has been sanctioned because of her “ongoing research speaking the truth about human rights violations against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang”

“In short, for having a conscience and standing up for social justice,” she said.

She said, “That the Chinese authorities should resort to imposing sanctions on UK politicians, legal chambers, and a sole academic is disappointing, depressing and wholly counter-productive.”

Dr Smith Finley has studied China for many years.

“I began my journey to become a ‘China Hand’ in 1987, when I enrolled at Leeds University to read modern Chinese studies. My first year spent in Beijing in 1988-89 – during which I also experienced the ‘Tianan’men incident’ – ensured that China entered my bloodstream forever, and the city became my second home,” she said. “I later focused on the situation in the Uyghur homeland (aka Xinjiang), to which I made a series of field trips, long- and short-term-, between 1995 and 2018.”

Dr Smith Finley said since taking up her post at Newcastle University in 2000, she has worked tirelessly to introduce students from the UK, Europe and beyond to the world of Chinese society and politics.

“I have prepared successive student cohorts for their immersion in Chinese culture, and have visited our students each year in situ across five Chinese cities,” she said.

“When China applies political sanctions to me, it thus stands to lose an erstwhile ally,” she said. “Since 2014, I have watched in horror the policy changes that led to an atmosphere of intimidation and terror across China’s peripheries, affecting first Tibet and Xinjiang, and now also Hong Kong and Inner Mongolia.”

“In Xinjiang, the situation has reached crisis point, with many scholars, activists and legal observers concluding that we are seeing the perpetration of crimes against humanity and the beginnings of a slow genocide. In such a context, I would lack academic and moral integrity were I not to share the audio-visual, observational and interview data I have obtained over the past three decades.”

“I have no regrets for speaking out, and I will not be silenced. I would like to give my deep thanks to my institution, Newcastle University, for its staunch support for my work and its ongoing commitment to academic freedom, social justice and inter-ethnic equality.”

Following the announcement of sanctions against Dr Smith Finley, more than 400 academics have written an open letter to The Times in support, asserting their commitment to academic freedom and calling on the Government and all UK universities to do likewise.

There are increasing demands from human rights activists to take action over China’s ‘soft genocide’ in Xinjiang. Tit-for-tat sanctions will not resolve the issue. That will take much firmer action from governments, organisations and individuals who are complicit in the subjugation of the Uyghurs, by buying Chinese products and accepting money built on their suffering.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”85″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world