Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”104667″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]“I found it empowering to be told I couldn’t talk about something,” said Gabby Edlin, founder of Bloody Good Period, on the stigmatisation of periods at the launch of the winter 2018 edition of Index on Censorship magazine.

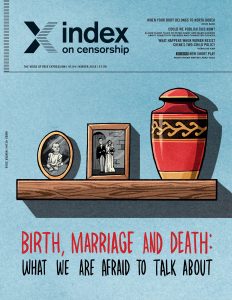

The issue, on the theme of birth, marriage and death, investigates what we are afraid to talk about and why. Whether it’s contraception misconceptions in Latin America, prejudice against interracial marriages in South Africa, or genocides around the world, a plethora of countries and topics were featured in this special report.

Taking place at Foyles’ flagship store in Charing Cross, London, which was once the world’s largest bookshop, Edlin was joined by award-winning author Emilie Pine, author of Notes to Self, and Xinran, the internationally best-selling author of The Good Women of China who also introduced the first women’s call-in radio show in China. The panel was chaired by Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine.

Edlin raised the taboo of period poverty, highlighting an unsettling scene in the Bafta-winning film I, Daniel Blake, in which a woman is caught stealing sanitary products and propositioned sex by a security guard in return for her freedom.

She said: “That was the moment that a lot of people woke up to the idea that, of course, women can’t afford this if they can’t afford everything else. But, everyone has experienced not having the product when you need it. It’s absolutely universal, it’s not just women living in poverty, it’s not just asylum seekers. Every single woman who has menstruated knows what it’s like to go without.”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”104670″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”104668″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”104669″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Xinran explained the pain of the controversial one-child policy in China: “Countryside women came to the city and realised girls have equal rights but in the countryside, the mother had to kill their daughters or give them away. Still now no-one talks about it.”

However, family policy is changing. “The Chinese published a new stamp because this year is a pig year – with a parent with three babies – that is a signal to a parent that it’s not one child, not two children, it is free now.”

“We think that we are now such an open, liberal society and you can say anything you want on Twitter, but actually we’re still very, very closed and we talk about things without really talking about them,” said Pine, whose Notes to Self breaks down the taboo of miscarriages and sexual violence.

“This woman, who I had never met before, came up to me and said, ‘I had a miscarriage two months ago and nobody knows’, and then just walked away. She walked away I think from having said it as well and from the need to say it. We need to tell our stories.”

For more information on the winter issue, click here. Find out why we find it impossible to talk about birth, death and marriage, according to Rachael Jolley. The winter podcast is also available on iTunes and SoundCloud.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1547210035015-71572e6c-f63e-3″ taxonomies=”8957″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”八九学运领袖王丹同著名作家欣然探讨天安门学运结果及其遗产”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

王丹 (Photo: Wikipedia)

薛欣然:首先我十分高兴有机会和你探讨发生在中国的历史事件。我们先说说事件发源地北京大学。1987年你从北京市第四十一中学毕业并考入北京大学国际政治系就读。但是1988年你转入历史系学习,为什么要转专业呢?

王丹:原因十分简单——政治专业需要学高等数学,我的数学不行我也十分讨厌数学。这是其中原因之一。另外一个原因是家庭因素。我的外祖父是四川大学历史系最早的毕业生之一,他毕生都从事历史教学。我母亲毕业于北大历史系。我当时也对历史感兴趣而且想避免学数学。也许您认为政治学是一门敏感的学科,但是我在北京大学学习了一年后,发现没有学到任何我感兴趣的东西——西方民主理论、人权等等。即使在北京大学也没人教授这些科目,所以我兴趣不大。

薛欣然:1988到1989那一年正是民主运动开始的时候,在历史系学习对你有重大影响吗?

王丹:我不认为和我所在的院系有关系。但是北京大学本身对我有很大的影响。北京大学所有的院系都有这种自由传统。二十世纪八十年代社会上有很多辩论,北大当时处于辩论的最前沿。当时有一种自由讨论的氛围,特别是关于社会改革的辩论,这也是我兴趣所在。我在北大度过了大约两年,对我影响深远。校园的气氛很重要,而不是所在院系。

薛欣然:文革过后的八十年代中国的大学仍然缺乏优秀教师。许多被下放的教师还没有返回教职,取代他们的人员水平堪忧。请问有没有对你影响重大的人或帮你树立理想信念的事?

王丹:国际政治系的一些老师对我影响深远,我和他们中的四五个老师关系特别好,我组织校园活动时经常向他们寻求建议。他们都是知识分子。历史系就不同了,因为我母亲的关系,系里的老师都认我,他们是看着我长大的。历史系更像我第二个家。然而国际政治的老师启发了我。他们一直陪我经历了六四。他们中不少人因为和我有联系或者因为自己参与六四运动而受到迫害。

薛欣然:到底是西方传统文化即古希腊罗马文明还是英美民主制度亦或是苏联解体或东方文明对你产生影响呢?

王丹:这些都不是。对我影响最深的还是中国传统文化。

薛欣然:你本人的专业是国际关系与国际政治。难道没有国际方面的影响吗?

王丹:其实灵感并非来自课堂或阅读。大学前两年主要是打基础,学习语言,共产主义史及其他一些课程。这些都不是灵感的来源,灵感主要来自于与老师和同学的日常交往。

薛欣然:他们都比你年长一些吧。

王丹:对,他们都大我十岁左右。

薛欣然:那他们都在三四十岁左右?

王丹:他们这一代人本应在文化大革命前完成中学学业,但是直到文革结束后他们才有机会上大学。他们对我影响很大,他们忧国忧民的文人传统对我影响深刻。整个六四运动是中国文化传统发展的一部分和西方没有特别大的关系。

薛欣然:你当时是北京高校学生自治联合会的负责人?

王丹: 对。

薛欣然:高自联是什么时候成立的?

王丹:应该是1989年四月,胡耀邦书记(当时的主要政治家和改革者)逝世之后。当时所有的大学都有自己的自治组织。高自联有来自各主要大学的代表——北京大学、清华大学、北京师范大学、中国政法大学、人民大学等。我是代表北京大学的常委。

薛欣然:你从什么时候意识到北京高自联以及学生运动对中国社会产生影响?他们是如何联合起来的?什么力量能让学生教授甚至记者和公众走上街头?

王丹:整个二十世纪八十年代一直都有学生运动的传统,北京大学更是如此。胡耀邦的逝世自然引起了学生们的关注。胡本人是共产党内自由派的代表,他的下台也与学生示威有关,所以胡的逝世让学生们感到特别的悲伤。在八十年代学生们每年都会抓住机会呼吁政治改革——1989年也不例外。

薛欣然:这一年为何如此不同?

王丹:我认为当时整个社会都希望民主改革。八十年代社会上这种思潮在不断积累和发酵。期间也受到不少挫折——反对资产阶级自由化运动、反对精神污染运动,到了1989年已经准备好要爆炸了。胡的逝世只是一个发泄口。另外一个原因是到了1989年人民越来越意识到经济改革过程中出现的问题,腐败是引发人们担忧的主要原因。那时人们还有些天真,如今中国人对腐败已是司空见惯。然而在八十年代腐败不仅让老百姓不满,还会引起公众愤怒。腐败问题同政治改革的愿望相结合使得民主运动在1989年获得广泛支持。每个人都认为社会需要更多的民主以及减少腐败。

薛欣然:军队开枪的时候你在哪里?到底发生了什么?

王丹:六月三号晚上我没有在天安门广场,我什么都没有看到。但是我接到了一个朋友的电话告诉我他看到有人死在他身边,周围有人脑浆四射。我的一个同学,也是我老师的儿子不幸遇害。大屠杀之夜我在北大,没有在天安门广场。

薛欣然:你当时什么反应?

王丹:当时我完全麻木无法思考,感到十分震惊。

薛欣然:是失望还是绝望呢?

王丹:我没有感觉,也没有任何想法。这样麻木了三天,辗转反侧,寝食难安。

薛欣然:你当时考虑过你自己的命运如何?

王丹:我根本没有考虑过自己的命运。我甚至都没有感到悲伤,没有任何感情,只是麻木。可能难以置信,但就是这样。

薛欣然:我能理解。

王丹:受到如此巨大的打击之后就是这种状态。接下来的两天我的脑子一片空白。

薛欣然:然后呢?

王丹:然后我就开始了逃亡。我在路上跑了一个月。我也没时间思考任何问题,每天都在赶路。

薛欣然:你认为是学生们存在战略错误,或是他们不成熟,还是对政府误解或低估呢?

王丹:接下来的十年我一直都在思考这一问题,但当时我没有时间去想。当时我只有20岁——思想还不够成熟,未能总结症结所在。

薛欣然:六四屠杀后你没有像其他学生一样流亡海外,你留在了中国。

王丹:对。

薛欣然:1991年你就被监禁了。

王丹:我于1989年7月2日被捕,然后就被囚禁。正式宣判是在1991年,被捕后我一直被拘留。

薛欣然:被捕后你感受如何?你是否认为这是你追求的理想的一部分呢?

王丹:没有什么伟大的想法,只是一种解脱。从6月3日向学生开枪后到7月2日被捕,我一直在逃亡,我实在精疲力尽。我一直在中国南方,当时感到受够了。我觉得宁可被抓也不想再逃亡下去了,于是我回到了北京——也是最可能抓到的地方。

薛欣然:你肯定知道生命受到威胁吧。

王丹:我其实我并不认为会有多糟糕,即使被抓他们也不会处决我。我只是觉得呆在监狱比逃亡好。

薛欣然:你为什么觉得他们不会处决你呢?

王丹:只是凭直觉。我和不少知识份子都所接触,我也十分了解中国政府的运作方式。对于中国政府而言,如此大规模的示威抗议以及向示威群众开枪,让全世界震惊。我确实不敢相信一个曾经在八十年代推行改革开放政策的政府一夜间变成了法西斯政权。但他们的确成为了法西斯刽子手,我之前还不相信他们会将学生围起并向我们开枪。

他们连纳粹都不如,纳粹也不会向人群扫射。我原本以为共产党不会下此狠手。我是学历史出身的,知道共产党不但不会杀像沈醉这样的国民党高级将领,而且还会封他当政协委员,他们只会向普通士兵动手。我在被通缉的学生领袖里排名第一,我相信他们不会杀我。

薛欣然:所以你的名气……

王丹:我的名气保护了我。当时我是这么想的

薛欣然:你最后被判刑四年。

王丹:对。

薛欣然:他们把你关在哪里?

王丹:秦城监狱。

薛欣然:秦城是专门关政治犯的地方。

王丹:我在秦城先关了两年然后转到北京第二监狱,总共关了快四年。

薛欣然:狱中生活如何?

王丹:正如你所想象的,情况很糟糕。大通铺、伙食很差……

薛欣然:多少人睡一张床?

王丹:我是被单独囚禁。

薛欣然:因为你是要犯。

王丹:算是吧。他们也这么看。

薛欣然:你在狱中怎么打发时间?

王丹:读书,尽可能多的锻炼身体。

薛欣然:监狱提供书给你读吗?

王丹:我可以给家里寄书单,家人可以寄给我。

薛欣然:你有机会见父母吗?

王丹:宣判前见过一两次。

薛欣然:司法程序怎么样?

王丹:中国没有法律更不要说司法程序了。都是假的。

薛欣然:他们还是走了过场。

王丹:对,一切都按程序走,假戏真做,我甚至还能提出上诉。但这又有什么意义呢?

薛欣然:你怎么看这几年的狱中生活?

王丹:其实我感觉自己很幸运——至少我这么年轻却能经历了这一切,这些经历给我带来了好运。我充分利用狱中时间读了很多书——我从来没有那么多的时间来读书。我无法想象自己如此幸运,有这么多的时间读书,无需做其他事情。

薛欣然:这四年时间改变了你对理想的看法吗?

王丹:不但没有改变,我的理想更加深刻。最初我对追求自由的想法还很模糊,但这四年树立了我的自由理念。

薛欣然:你认为你做出了正确的选择吗?

王丹:当然,我很清楚。只有坐过牢的人才能体会到自由是多么的宝贵。很多人都浪费了自由不知道它的价值。

薛欣然:我完全赞同你的观点。你释放后不久再次被捕。他们当初为什么要释放你呢?

王丹:当时我刑期快结束,他们提前三个月将我释放。国际社会为了我恢复自由一直都施压。我想他们也就是做个样子——我距离正式释放只差几个月。

薛欣然:你的家人做出了不少努力吧?

王丹:我的家人当然也做出不少努力,但真正奏效的是国际压力。当局作出姿态提前几个月释放我——虽然这是一个虚伪的姿态。

薛欣然:你为什么会再次被捕入狱?

王丹:从1993年2月释放到1995年5月再次被捕的两年零两个月,我一直呆在北京。我依然积极参与政治活动,再次联合其他民运人士参与活动,同时我也在国内各地旅游。政府认为我依然为民主发声,他们不喜欢这样。

薛欣然:政府应该很快就知道你依然从事民主运动——为什么他们仍然给你两年自由时光呢?

王丹:也许他们只是失去了耐心。我释放后,他们不敢马上再抓我。过了两年他们可能觉得我取得了不少成就,而且参与的人越来越多。到1995年我们发出公开信后,政府就出手禁止我们的活动。也许他们担心民主运动会再次爆发。

薛欣然:两次被捕之间你感觉政治气氛有何不同?

王丹:第一次被捕时情况更糟糕——天安门屠杀刚刚发生,大家都命悬一线,很多人都被抓。1995年时只抓了几个人,没有1989年那么严重。

薛欣然:你刚才提到你联系到1989年民主运动参与者并且开始起草公开信?具体有多少人,他们来自何地?

王丹:我们最后一封公开信有一百多签名者,他们来自全国各地?

薛欣然:他们都是学生吗?

王丹:他们都是当年学运的参与者,只是他们不再是学生了。六四之后他们都被开除了。

薛欣然:你们想释放什么信号?你们是在寻找补救措施,还是想继续民主运动?亦或是其他呢?

王丹:我们是希望延续1989年民主运动的理想,呼吁进行政治改革。我们认为当时没有任何政治改革的信号,这就是症结所在。我们之前没有提出人权问题,但是我们认为保护人权应该是政府政策的重要组成部分之一,因此这一次我们增加了人权内容。我们的公开信呼吁进行政治改革和保护人权。

薛欣然:民主运动后来为什么失去活力了呢?

王丹:原因很复杂。这漫长的二十年是一个因素,民主运动随着时间的推移渐渐失去活力。别人的情况我不了解,对我们来说就是这样。有人结婚了,在美国有了新的生活和工作,所以就没有那么多的时间和精力投入民主运动。其次,民主运动内部也存在一些问题。大家对民运所采取的方式方法甚至财务问题都有所争论。这让许多人感到失望,我为此也感到十分悲伤。再次,现在经济是王道。许多人对政治失去了兴趣。这也是后极权社会的特征。再也不会像1989年那样对政治感兴趣。其中有我们自己的原因,也有我们生活的时代的原因,有些只是一个自然的过程。

薛欣然:你现在在海外生活了多年,但是你从来都没有回过中国?

王丹:政府不让我回国。

薛欣然:你想回国吗?

王丹:当然想回啊,我每天都想回国。

薛欣然:为什么呢?

王丹:我是被迫离开中国的;我从来都没打算要在海外生活。我父母还在中国,这也是我想回国的主要原因。

薛欣然:如果有机会回去,你还会坚持你的理想信念吗?

王丹:当然了,可能方式会不同——我毕竟已经四十岁了。

薛欣然:这二十年里你有哪些变化?

王丹:当时我们只有二十多岁,我们给自己太大的责任,设定了一个巨大的目标,而且要求自己必须将其实现。然而现在我会认为只要努力做到最好,成功与否并不重要。当年的失败让人感到失望甚至不安。现在我不能回家,你可以认为我仍然受到迫害,但这并没有影响我。这是我思考问题方式的巨大变化。

薛欣然:如果有机会重新选择,你还会这样做吗?

王丹: 嗯,学生运动、组织学生游行等等之类的事情我还是会做的,但是会有一些变化。毕竟已经过了二十年,中国已经发生了巨大变化——我们的要求也会有所不同,我们使用的技术手段也不一样。

薛欣然:如果你有机会能改变三件事,你会怎么做?

王丹:首先,只要绝食和静坐能坚持到五月底,我们就应该收场,但当初我们没有。其次,我们过分地关注学生运动的纯洁性,我们对知识分子的建议十分警惕,害怕被人利用。同样我们对共产党内人士也保持谨慎的态度。我再也不会那样做,我会尽力寻求支持与建议。

薛欣然:如果你有机会同当下的中国年轻人对话,或说服他们做点什么,你会说些什么?

王丹: 我会告诉他们反对共产党并不等于不爱国。我们都希望中国变得强大,但仅凭经济和军事实力无法赢得别人对我们的尊重。一个真正强大的国家需要民主与文明。我们都同意, 我们希望中国变得更加强大,我们需要讨论的是国家如何赢得真正的尊重。

薛欣然:这二十年里,你试图理解你的敌人吗?

王丹:当然啦。我母亲是研究中国党史的,我的博士论文也是关于中国共产党的。如果没有深入了解中共,我就不可能拿到学位。我深刻认识中国共产党。

薛欣然:那么你如何解释中国政府对待学生运动的态度和行为呢?

王丹:中国共产党是一个建立在暴力与谎言的政党,并使用暴力同谎言手段取得政权。很自然他们通过使用对大众的恐怖手段来把持权力。大屠杀最终目的是制造恐惧,这确实奏效了。即使今天大多数人都不愿站出来反对极权主义。

薛欣然:使用恐怖手段是共产党的独有手法吗?

王丹:这是中国共产党的独特的手法,和苏联或纳粹德国还不一样。中国作为一个集权统治国家,还是非常独特的。

薛欣然:中国历史上也这样吗?

王丹:我再次强调一下,不一样。国家暴力在过去从来没有像共产党这样延伸到社会各个层面,触及到灵魂。历史上没有像文化大革命这样的政治运动,苏联纳粹德国都没有,文革只发生在中国。其中有许多复杂的因素,我的博士论文里有具体讨论。但我敢肯定的是它是独一无二的,这也是共产党能把持住权力的原因之一。

薛欣然:你认为中国需要共产党吗?

王丹:如果我们是民主制度,那么各种政党都有一席之地。那当然也包括中国共产党。所有政党的政治宣传事实上都是一种洗脑,其目的是消除你在西方能看到的强烈个人主义或反对文化。其次,政党利用这些宣传活动使人民反对彼此,使每个人都成为犯罪成员。第三,虽然压制通常会引起抵抗,但如果镇压残酷的话,就不会有反抗,民众的承受能力有限。第四,二十年的经济改革让人们分享收益从而也分散了他们的注意力。其基本策略是镇压冲突,然后再开放某些领域,这一手法相当成功。这也是共产党能继续下去的四个理由。

薛欣然:你认为共产党的存在有一定的理由吗?

王丹:当然。中国传统文化存在一些问题,比如我们是建立在集体主义为基础,这意味着我们对政府过于信任——这使得共产党能够长期存在。

薛欣然:作为一个历史学者,你认为这是一个纯粹的中国现象还是一个远东现象?韩国、日本、马来西亚和新加坡社会比我们更民主吗?

王丹:所有的儒家社会都十分相似,例如新加坡和其他一些国家。然而他们国家更小,因此能够迅速改变,这样就剩下中国。如果你想寻找深层次的文化因素的话,那就是儒家思想。但事实上有很多原因,文化只是其中的一部分。例如国家暴力也是一个非常重要的因素,可能发生在任何地方。

薛欣然:我认为研究这些问题不是因为对其不满或心怀仇恨。

王丹:我同意。

王丹:我认为我们研究的目的是为了明天,以确保将来更少的人受到暴力或镇压。至关重要的是,人们应该考虑这种政权如何产生、发展、如何防止它变得更糟,控制未来的社会。这不是向后看,我相信你同意这种看法。

王丹:历史研究都是在展望未来。

薛欣然:如果中国采用美式或英式的选举制度呢?

王丹:我认为这甚至都不是一个问题。没有人要求中国在一夜之间进行民主选举。

薛欣然:但如果我们假设呢?

王丹:这不可能。西方民主不会突然出现。

薛欣然:可能不会一夜间出现,但是你认为有可能吗?

王丹:不可能。中国不会采取西方民主制度;它应该有自己的中国特色。

薛欣然:理想情况下这会是什么呢?

王丹:台湾方式更可行。这种政治变革不是通过流血冲突,而是自上而下的改革意愿结合自下而上的压力。这是我希望在中国看到的,人民与政府达成协议,然后进行权力转移。

薛欣然:我读到报道说你发现当今的中国年轻人过于自私和物质主义,而你年轻的时候,社会上有一种爱国主义和责任感,是否如此?

王丹:今天的年轻人,至少我接触的中国年轻人都只关心自己而不是国家。这是一个普遍的现象。至少不仅是我有这种想法,大家都这么认为。至少我发现年轻人们讨论的话题很不同。

薛欣然:你会鼓励年轻人吗?帮助他们巩固他们的信仰,或是让他们多多思考,还是帮助他们了解中国?

王丹:我当然会鼓励他们。我四十岁了,老了,但年轻人有他们的热情。

薛欣然:但在西方发达国家,你这是黄金岁月,不能说自己太老了。

王丹:我觉我太老了。我想二十岁时应该是热血青年。我现在四十岁了,思考问题更理智。但我认为现在二十岁的中国年轻人用四十岁的人思维方式,这的确是中国的国家悲剧。我会鼓励他们,告诉他们要冲动,犯一些错误,不要太理性——这都没有关系。这是你的青春,享受青春。

王丹于1998年获释,释放后流亡美国。他获得哈佛大学博士学位,曾任教于台湾国立清华大学

薛欣然曾在中国担任记者和电台节目主持人,现居住于伦敦。她的作品包括《中国好女人们》、《中国目击者》及《给我买片天》

本文最初发表于《审查指数》杂志2009 38:2期

[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1562079335291-07d0e018-98cd-1″ taxonomies=”29029″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine produces regular podcasts in which we speak to some of the most interesting writers, thinkers and activists around the globe.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine produces regular podcasts in which we speak to some of the most interesting writers, thinkers and activists around the globe.

Click here to see what’s in our archive.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, Index on Censorship magazine explores the free speech issues from around the world today.

Themes for 2018 have included Trouble in Paradise, The Abuse of History and The Age of Unreason.

Explore recent issues here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Vital moments during our lifetimes are complicated by taboos about what we can and can’t talk about, and we end up making the wrong decisions just because we don’t get the full picture, says Rachael Jolley in the winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Birth, Marriage and Death, the winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taboos, especially around death and illness, can stop people asking for help or finding support in times of crisis” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Birth, Marriage and Death” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores taboos surrounding birth, marriage and death. What are we afraid to talk about?

With: Liwaa Yazji, Karoline Kan, Jieun Baek[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”104225″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Liwaa Yazji, Karoline Kan, Jieun Baek, Neema Komba, Bhekisisa Mncube, Yuri Herrera, Peter Carey, Mark Haddon”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”104226″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Birth, Marriage and Death”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”104225″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The winter 2018 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with Times columnist Edward Lucas, Argentina-based journalist Irene Caselli, writer Jieun Baek and law lecturer Sharon Thompson

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”104225″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The winter 2018 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with Times columnist Edward Lucas, Argentina-based journalist Irene Caselli, writer Jieun Baek and law lecturer Sharon Thompson

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]