28 Mar 2018 | Event Reports, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“We must distinguish the things that are intellectually dishonest and aimed at persuading, which is traditionally called propaganda, and the things where people are trying to give you general information, which doesn’t have the absolute intention of persuading you,” said The Times columnist David Aaronovitch at a panel at the Essex Book Festival.

Aaronovitch, also Index’s chair, was discussing the role of propaganda with leading expert on the darknet and technology Jamie Bartlett and Chinese-British author Xinran, who was the first woman to have a late-night radio show in China.

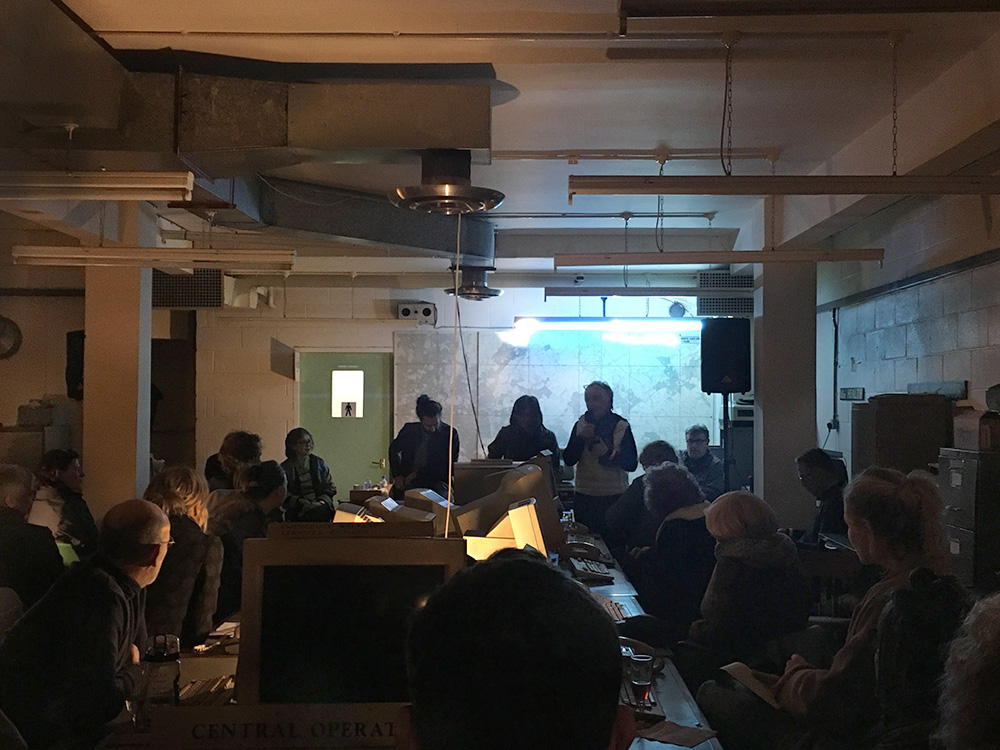

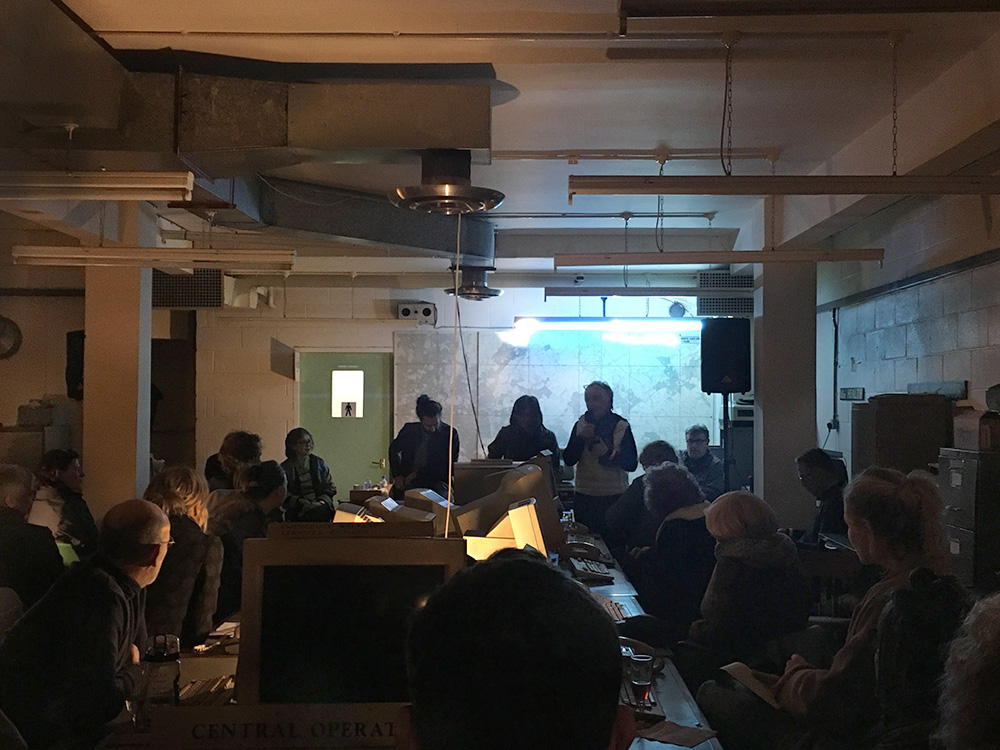

The panel, chaired by Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley, was part of the festival’s Nuclear Option day at the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker, a twisted network of dimly lit hallways and musty rooms that lie beneath a field.

Around 75 attendees gathered on March 25 to listen to Index’s panel and attend other workshops, screenings and performances part of the festival. Everyone at the festival was free to roam the enormous bunker and walk amongst Cold War history.

Passing signs that instructed people to “use water sparingly” and dusty machines that co-ordinated evacuation procedures, attendees eventually made their way to a desk-lamp lit room and were seated at long desks with old, monochrome computers.

Looking at the current state of propaganda, Bartlett said “everything has become more emotional and gut-driven,” adding that politics has not become as informed as people had hoped, but now become “heuristic because people are just showered with information”.

Aaronovitch called the inundation of information the “age of cacophony”.

What is emerging, according to Bartlett, is a “horrible new form of soft surveillance that has encouraged a great conformity among people”.

Xinran said China’s current propaganda, especially on social media, along with party control of education and the legal system has led to “one voice” in China, despite age gaps, class, education and geographical residence.

The author talked about her past experiences with censorship and Chinese propaganda when she worked on her radio show in China. She explained that there was a list of restrictions she had to abide by, these included never mentioning the British media, Western religions or love and relationships. The author said during her show she was able to tackle subjects that were previously taboos on Chinese radio.

“My work was stopped for three months when I spoke about homosexuality,” said Xinran. “This type of censorship was very strong until 1997, but it has now escalated to constant censorship, due to social media.”

Looking at the future of propaganda and its direction, Bartlett added that he can “see much more reliance on coercive digital types of surveillance being absolutely necessary just to maintain some type of law and order in society, especially online, which could make us a much more authoritarian society”.

This led Bartlett to predict that “already authoritarian countries are going to become much more so, and already very free countries are going to become even more free to the point where it might collapse”.

He believes we are shifting to a “Huxleyan society,” which Aaronovitch called the “algorithmic society”. Both felt one big question was, who governs the algorithms?

Aaronovitch noted that it depended on who was controlling the algorithms, saying that if the EU requested that Google to reveal its algorithms, it would be problematic; however, governmental algorithms used for policing in a democratic society were essential.

With reference to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which was mentioned numerous times during the panel, Bartlett noted that the worry over “Cambridge Analytica’s 5,000 data points on every single American doesn’t compare to what’s coming”.

“We are going to be creating a lot more data in the future,” said Bartlett. “And it is going to be shared and it is going to be used by political actors.”

Aaronovitch advised the audience that the best way to combat propaganda is to ask yourself, “‘Am I wrong?’. The point is to ensure no one is “completely blinded by initial preferences”.

Similar to Aaronovitch’s warning to predisposed biases, Xinran calls for “independent thinking,” and equated the consumption of information with eating.

“In Chinese we say you become what you eat,” said Xinran. “And your brain is the same way. You become what you are by what you believe”.

Hats off to @EssexBookFest! An incredible day at the Secret Nuclear Bunker. Brilliant discussion with @IndexCensorship, @JamieJBartlett, @DAaronovitch, @londoninsider and #Xinran, topped off with a silent disco of music banned from Estonia, with obligatory gherkins and vodka 👍 pic.twitter.com/HVtfrVDRb1 — Radical ESSEX (@RadicalEssex) 26 March 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522237614911-7109bbff-bdcf-1″ taxonomies=”2631″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1 Mar 2018 | China, News

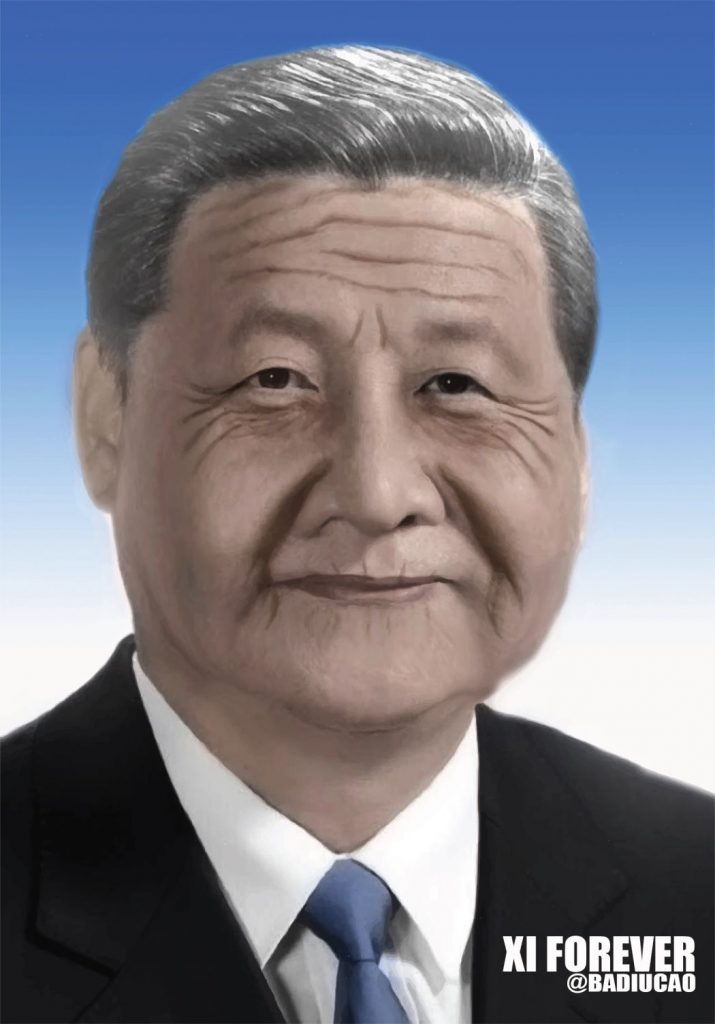

With the historic announcement at the weekend that China would end the two-term limit on presidents, meaning the current leader Xi Jinping could be president for life, it created an online storm.

People took to the popular Chinese social media apps Weibo and WeChat to express either disdain and outrage. It didn’t take too long for the country’s well-oiled censorship apparatus to swing into action and ban all of the obvious terms related. Within hours, you couldn’t say “I don’t agree”, “migration”, “emigration”, “re-election”, “election term”, “constitution amendment”, “constitution rules”, “proclaiming oneself an emperor”, “Yuan Shikai (Former Emperor)” and “Winnie the Pooh” (more on this soon).

At the same time, Chinese citizens created and widely shared a series of memes. Most of these have since been removed, but not before enough people saw them, screenshots were taken and they were spread on media beyond the censor’s reach. Here’s an overview of some of the best:

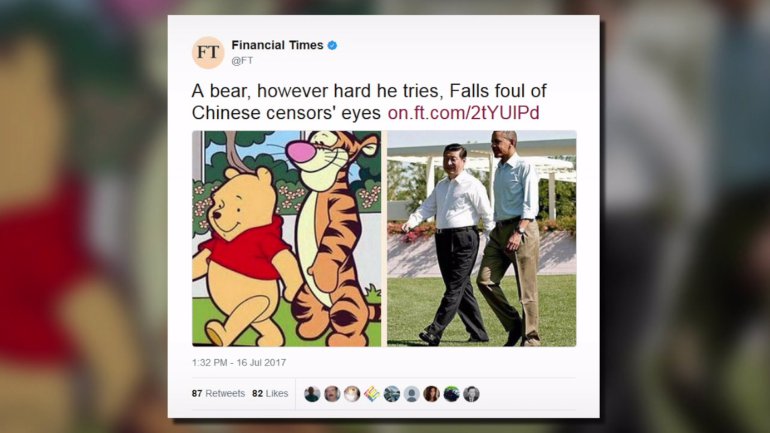

King Winnie

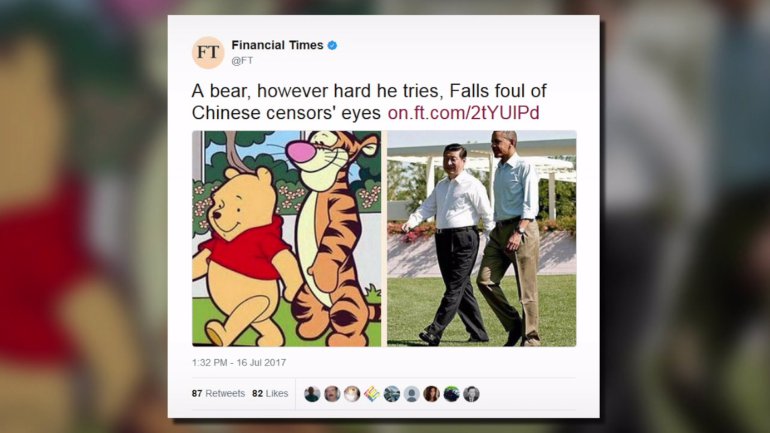

The world’s favourite cuddly teddy bear, unless you’re a Chinese leader. After a meme likened the cartoon character with the Communist Party leader went viral in 2013, Winnie the Pooh became a popular meme when riffing Xi – and arguably the world’s most censored children’s book character. That has not stopped people persisting with the animated representation of the leader. In response to the new proposal, several of the following memes circulated:

The original meme that prompted the government to ban Pooh in 2013.

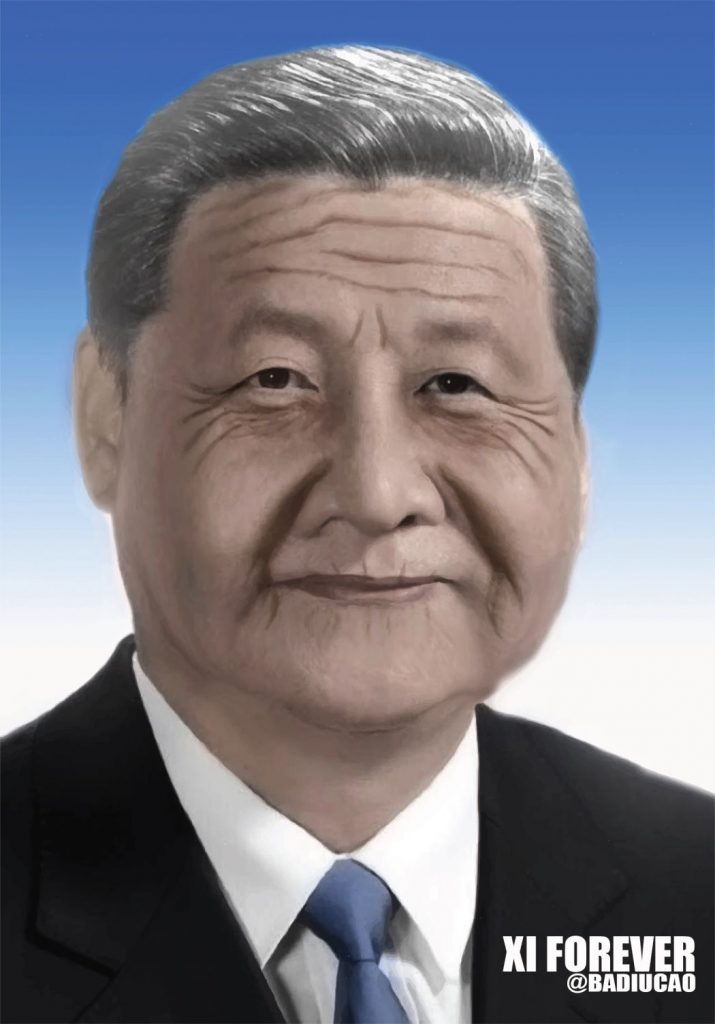

Another oldie but goodie expressing Xi’s disdain for Pooh, created by cartoonist Badiucao in the China Digital Times.

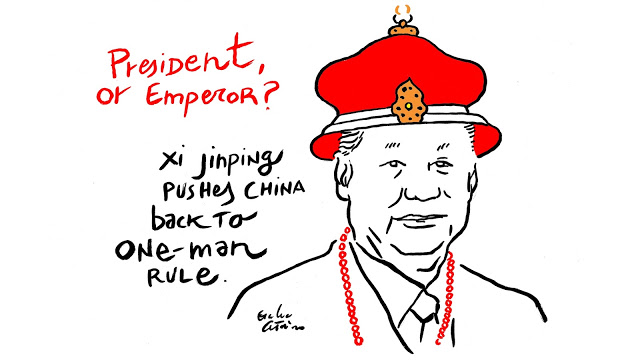

Emperor Xi

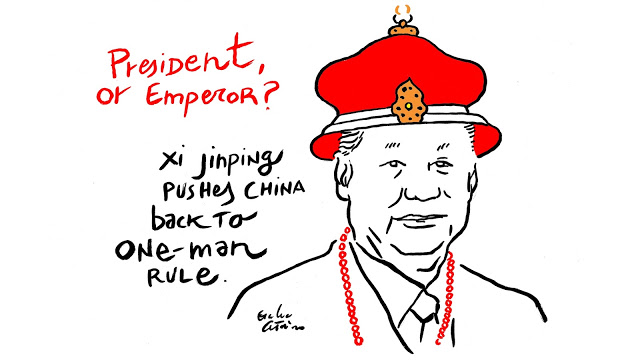

An obvious one here. Graphics emerged with references to past emperors of China, emphasizing the point that this new proposal is reminiscent of past Chinese rulers and dictators. Some of these graphics censored include:

Cartoon created on political activism website, ChannelDraw.

Graphic created after the announcement by Badiucao, prolific political activist and cartoonist.

Silver lining?

Perhaps the best of the memes, combining as it does a joke about Xi’s term extension and a joke about the common Chinese pressure to get married. It reads: “My mom said that I have to get married before Xi Dada’s term in office ends. Now I can breathe a long sigh of relief.”

Don’t forget the bunnies

While the latest news is sure to keep the censors busy for some time, they’ve been waging another war in China this year against #Metoo, which has recently come to the country and has not been well-received by a government uncomfortable with any form of protest (read our article on protest in China here). Initially the hashtag #woyeshi went viral, which literally means “me too”. When that was banned, people got creative. Introducing the rice bunny. Rice in Mandarin is mi and bunny tu, pronounced basically “me too”. Now China’s internet is awash with images of bunny and rice combos, that is until the censors catch up. Bunnies and Pooh bears – China’s internet might be censored, but it’s never boring.

The Rice Bunny is against sexual harassment. Image from @七隻小怪獸 on Weibo

16 Jan 2018 | News, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”As China’s economy slows, an unexpected group has started to protest – the country’s middle class. Robert Foyle Hunwick reports on how effective they are”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

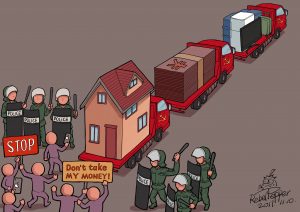

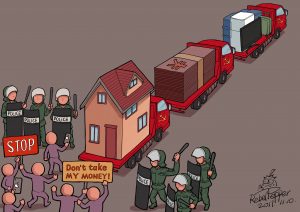

China’s middle class protest, Rebel Pepper/Index On Censorship

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Park Avenue, central Beijing, is known for its luxurious serviced apartments, landscaped gardens and Western-style amenities, certainly not its dissident population. Yet, strolling past the compound one weekend, I was surprised to see a protest in progress.

A small group of around two dozen had assembled with signs and were milling around outside a locked shop, arguing with a harassed-looking man in the Chinese junior-management uniform of white shirt and belted black trousers. The cause of all the chaos: a swanky gym that had opened in the gated community a few months before, promising unparalleled 24-hour access to upscale fitness machines and personal trainers, had used a recent public holiday to sell all its equipment and, apparently, make off with everyone’s membership fees. Now a dispute was in full swing over who was going to take responsibility for this fiasco. The building management, who presumably had vetted the gym? The police? The residents?

The protest was a rare sighting in the capital of a country where free speech has always been tightly controlled by the government, and has become almost completely stifled under the current leader, Xi Jinping. Xi formally enters his second five-year term as general secretary, state president and “core” of the Chinese Communist Party in March, and fear for the future of political freedom and protest is at an all-time high. That paranoia is most acutely felt in the most unlikely of quarters, the main beneficiaries of the country’s economic prosperity, the Chinese middle class.

For those living just across the way, the uproar over the gym provided a rare piece of street theatre. This audience of weather tanned men and women from the country’s interior are the ones who run the market stalls, taxis and tool shops that skirt the towers. Even in central Beijing, these kinds of cheek-by-jowl living arrangements are still fairly common. Migrants run businesses out of ramshackle stores, leading hardscrabble lives beneath grandiose skyscrapers such as those in Park Avenue, where the well-heeled residents’ biggest concern is usually which international summer camp they should choose for their children.

Yet this poorer demographic is declining in China’s most-developed urban areas. Unregistered workers are being steadily forced from the cities whose growth they once spurred, ejected by implacable officials who often use passive-aggressive methods (erecting brick walls; suddenly enforcing long-stagnant municipal regulations) to make their working lives untenable. Blue-collar migrants have little leverage to protest these decisions, and are moving away, leaving behind middle-class homeowners who have no interest in complaining on their behalf. Indeed, most are happy to see them gone. The middle class prefer to consider themselves safe, content in the knowledge that their own rights are secured by lease- holds, law and lucre. All they have to worry about are gym memberships.

This is, or at least was, the essence of the unspoken contract that emerged in the bloody aftermath of the disastrous protests in Tiananmen Square during the summer of 1989. Prior to that, “the demands of politically active urbanites were aimed squarely at the national leadership and national policy – for political liberalisation, a free press, and fairness in local elections”, noted Andrew Walder in Untruly Stability: Why China’s Regime Has Staying Power.

After 1989, former leader Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms dramatically shifted the landscape to one that focused on individual prosperity at the expense of any greater good. Stay out of the politics, the government seemingly implied, and we will stay out of your lives – a “deal” that helped drive one of the greatest booms in history. Like any agreement left unspoken, though, this pact has turned out to be worth rather less than the paper it was written on.

Now as growth slows and debts accumulate, the cracks are growing more evident in the propaganda façade of peaceful prosperity, one in which absurdist posters increasingly plead “Every day in China is like a holiday”, while uniformed soldiers patrol the capital’s streets and whole neighbourhoods are torn down without warning.

Some now refer to a “normal country delusion”, the comforting myth that being a law-abiding, middle-class citizen is a bulwark against authoritarian anger. The Germans have another word for it: mitläufer – getting along to get by; the hope that obeying rules protects oneself in the event of accidentally breaking any.

The complacency of this particular fantasy was blown apart, in spectacularly literal fashion, by the chemical explosion that occurred in the coastal city of Tianjin in the early hours of 12 August 2015. Similar blasts happen on a semi-frequent basis throughout China, usually the result of muddled regulations, lax oversight and complicity between officials, developers and businessmen. Hidden in the country’s vast interior, these disasters usually pass without comment, with protests swiftly stifled and any cover- age strictly limited to terse, state-approved reports. According to the New York Times, “68,000 people were killed in such accidents [in 2014]…most of them poor, powerless and far from China’s boom towns”.

Tianjin – a city bristling with international enterprises, and easily reachable from Beijing via high-speed rail in just 30 minutes – was a very different affair. Reporters from the Chinese and international media descended on the scene within hours and the story was carried for days, providing an almost unheard of level of scrutiny.

The government’s disaster-management skills were on full display: untrained junior firefighters sent to tackle a chemical blaze for which they were fatally unequipped; a series of disastrous press conferences; officials sacked and replaced on an almost daily basis; then, finally, a total media shutdown.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”They’ve taken everything from us. We’ll take everything from them.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

But amid the disarray, the overriding narrative concerned the thousands of middle- income homeowners who had been killed, injured or displaced as a result of zoning irregularities that allowed 11,000 tonnes of highly volatile chemicals to be stored next to the new (and now obliterated) residential blocks within the blast zone. As one blogger observed, these were the people who “maintain a noble silence on any public incident you’re aware of. On the surface, you look no different from a middle- class person in a normal country.”

Writing on microblog service Weibo, user Yuanliuqingnian noted that when these same apolitical families gathered near the site, first to mourn, then – as the official silence grew deafening – to protest their treatment, an un- fortunate realisation set in. They “discovered they’re the same as those petitioners they look down on… kneeling and unfurling banners, going before government officials and saying ‘we believe in the Party, we believe in the country’.

The homeowners realise, much to their embarrassment, that, after an accident, there’s really #nodifference between us and them.”

A year on, Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao reported that the treatment of these middle-class victims remained taboo: family members of the firefighters were arrested for mourning their dead sons, while a collective of homeowners protested anew that the government had still not compensated them for their lost properties. They’d become the very people they disdained: what older Chinese called yuanmin –“people with grievances”.

In some instances, government policy unwittingly forged these resistances. I met one family in Shanghai whose home had been demolished for the 2010 World Expo. After months of protest, local officials ensured that both parents lost jobs or promotions and their two sons, in their late teens, were denied graduate placements. The result was four enraged adults with nothing to lose. “They’ve taken everything from us,” the mother vowed. “We’ll take everything from them.” Such outbursts echo the sea change in mainland protest, from the political to the personal. Today’s yuanmin “invoke national law and charge local authorities with corruption or malfeasance” as Walder observed.

“Protest leaders see higher levels of government as a solution to their problem, and their protests are largely aimed at ensuring the even-handed enforcement of national laws that they claim are grossly violated.”

These grievances are still highly risky and liable to be dispersed (or, worse, ruthlessly punished), and are only occasionally and specifically effective. Sometimes, officials might be motivated by political imperatives to quickly mollify any protesters; sometimes they might be compelled, for the same reasons, to thoroughly quash them.The result is that, despite being afforded exclusively bourgeois privileges such as healthcare and education, China’s middle class exists “in constant fear of losing everything”, writes Jean-Louis Rocca in his book, The Making of the Chinese Middle Class.“They live in an unstable world, and they are never sure where they are on the social ladder. They imitate the bourgeoisie’s life- style and they strive to avoid falling into the category of ‘workers’.”

“Zhang”, a Shenzhen-based journalist who asked for a pseudonym for fear of official repercussions, blamed the “growing pressure in Chinese society and the instability of government policies”. In the case of housing, “[some] had already scraped together barely enough to buy a house, now they had to come up with more money in the short term. In this way, even though you are ‘middle class’, you don’t quite feel like you are living the life a middle- income person deserves”.

Exacerbating matters is the lack of options available to those who have been wronged, swindled or otherwise denied their supposed rights. “Some don’t really know what options they have,” Zhang told Index. “Some are aware they can’t really do anything, in fear they might lose more of what they have.”

Ingrained anxieties are apparent in the issues that do force members of the smart-phone-clutching middle class off their We- Chat groups – where posts about “sensitive” issues are quietly erased by sophisticated censorship algorithms – and into the less- forgiving arena of public protest.

In May, dozens protested outside Beijing’s housing authority against new regulations that prevent homeowners buying multiple apartments, saying that the rules trampled on their property rights. There were similar, and partially successful, demonstrations in Shanghai the following month over residen- tial zoning rights. In this case, the municipal authorities chose to blame property develop- ers as they backed down, accusing them of “distorting the policy”.

In July, thousands staged the biggest protest in Beijing in years, after a pyramid scheme they’d invested in was declared illegal, with millions in funds frozen.

The response to the disruption was harsh. After detaining 64, police said they had “released some who created minor harm, but made good confessions. However, there will be a crackdown on those plotting and inciting the gathering.” Some are realising that this is often the case. Many others, though, are in denial about the insecurity of their wealth. Comparing Chinese society to an “atmospheric tank”, scholar Zeng Peng warned, in a paper on protest, that “to prevent the gas tank bursting, on the one hand [the government] should stop the production of grievances, on the other hand repair the safety valves”.

There have never been strong systemic means for resolving disputes in China, other than by drawing public attention. In imperial eras, yuanmin would bang gongs or throw themselves in front of visiting envoys from Beijing to plead their case, believing that the emperor’s officials would be outraged by the local rot. Today, the commonest resort for everyday yuanmin is to take to social media to blow off steam or report malfeasance.

Those without the audience or the means might take things further, travelling to Beijing to lodge a petition of complaint, an archaic and ineffectual process that dates back to ancient times, and whose continued necessity is an embarrassment for Beijing. As if recognising this, while fearing the consequences of addressing it fully, the current administration seems intent on shearing off access to any valves they don’t completely control, even while it struggles to quell the multiplying means of production.

Even when protests seem successful, the effects can prove deleterious in the long term. As Tianjin proved, the middle classes may find their calls for change ignored, the rules changed abruptly or their actions punished, just like their poorer neighbours. And those aggrieved Park Avenue protestors who’d demanded their membership fees back? When I returned a half-hour later, they’d disappeared too; not a single one remained, nor any sign to indicate they’d ever been there.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Robert Foyle Hunwick is a freelance journalist based in Beijing

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91419″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228908534694″][vc_custom_heading text=”The people’s horror” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228908534694|||”][vc_column_text]September 1989

Index’s Asia specialist, Lek Hor Tan, reviews why China’s human rights record has long been glossed over and looks at the history that led up to the massacre in Tienanmen Square.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89086″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422013495334″][vc_custom_heading text=”Border trouble: china’s internet” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013495334|||”][vc_column_text]July 2013

Chinese government uses sophisticated methods to censor the internet. Despite citizens’ attempts to circumvent barriers, it has created a robust alternative design.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89073″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422013513103″][vc_custom_heading text=”Stamping out the moderates ” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013513103|||”][vc_column_text]December 2013

Chinese authorities are cracking down on popular New Citizens’ Movement, even though its leaders are trying to protect rights already guaranteed under the constitution.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In homage to the 50th anniversary of 1968, the year the world took to the streets, the winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at all aspects related to protest.

With: Micah White, Ariel Dorfman, Robert McCrum[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Dec 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, China, Fellowship, Fellowship 2017, Statements, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rebel Pepper, Chinese artist, is the 2017 Freedom of Expression Awards Arts Fellow.

“China has little to no freedom of speech and its people are constantly living in fear.”

— Rebel Pepper (Wang Liming), Cartoonist, 2017 Arts Fellow

Silence is the oppressor’s friend. Targeting those who challenge corruption and injustice – like this year’s Freedom of Expression Awards Fellow Rebel Pepper – is the favoured tool of those who seek to crush dissent. We cannot let the bullies win.

With your help, each year we are able to support writers, journalists and artists at the free speech front line – wherever they are in the world – through Index Fellowships. These remarkable individuals risk their freedom, their families and even their lives to speak out against injustice, censorship and threats to free expression.

I am writing now to ask you to support the Index Fellows. Your donation provides the support and recognition these outstanding individuals need to ensure their voices are heard despite the restrictions under which they are forced to live and work.

Your support will help winners like Rebel Pepper, censored by Chinese authorities for his cartoons lampooning the government. Forced into exile, he’s now working for Radio Free Asia and living in the USA with his wife and newborn child, and looking for opportunities to showcase his work to a wider audience.

Your support will help winners like Rebel Pepper, censored by Chinese authorities for his cartoons lampooning the government. Forced into exile, he’s now working for Radio Free Asia and living in the USA with his wife and newborn child, and looking for opportunities to showcase his work to a wider audience.

Working with Index, Rebel Pepper also hopes to reach more of his original fans inside mainland China from whom he’s been cut off for several years. “There are a lot of terrible things recently” says Rebel Pepper, “the CCP’s control of society is becoming more and more severe, people get less and less chance of real news from outside, and vice versa.” Nonetheless, “this award give me energy to keep walking on the cartoon creative road”.

I hope you will consider showing your support for free speech and the Index Fellows. A gift of £500 would support professional psychological assistance for a fellow; a gift of £100 helps them travel to speak at more public events. A gift of £50 helps us to be available for them 24/7. You can make your donation online now.

Please give what you can in the fight against censorship in 2018. Make your voice heard so that others can do the same.

Thank you for your support.

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO

P.S. The 2018 Index on Censorship awards will be held in April. To find out more about the awards including previous winners, please visit: https://www.indexoncensorship.org/awards

Index on Censorship is an international charity that promotes and defends the right to free expression. We publish the work of censored writers, journalists and artists, and monitor, and campaign against, censorship worldwide.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1513332894550-8daa2ef8-543f-7″ taxonomies=”9021″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Your support will help winners like Rebel Pepper, censored by Chinese authorities for his cartoons lampooning the government. Forced into exile, he’s now working for Radio Free Asia and living in the USA with his wife and newborn child, and looking for opportunities to showcase his work to a wider audience.

Your support will help winners like Rebel Pepper, censored by Chinese authorities for his cartoons lampooning the government. Forced into exile, he’s now working for Radio Free Asia and living in the USA with his wife and newborn child, and looking for opportunities to showcase his work to a wider audience.