17 Oct 2016 | mobile, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

|

Battle of Ideas 2016

A weekend of thought-provoking public debate taking place on 22 and 23 October at the Barbican Centre. Join the main debates or satellite events.

Comedy and censorship: Are you kidding me?

Is the fear of offence killing comedy? Jodie Ginsberg, Timandra Harkness, Will Franken, Tom Walker and Steve Bennett with chair Andrew Doyle.

When: 23 October, 10-11:30am

Where: Cinema 2, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas

From hate speech to cyber-bullying: Is social media too toxic?

What of the free speech of those harassed into silence by a stream of abuse? And what of the abuse itself, consisting, as it so often seems to, of fantasy punishments and name-calling? Is that speech worth defending?

When: 22 October, 4-5:15pm

Where: Pit Theatre, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas |

We live in serious times, what with civil wars, US elections and the threat of Marmite rationing. But there’s always room in the news for outrage about a joke.

In the last few days Simon Cowell has been reprimanded for making a “back door” joke to X Factor host Rylan Clark-Neal, and singer Lily Allen for a stupid pun on the word “gyppo,” recorded several years ago. Meanwhile, Canadian comic Mike Ward, who was fined $42,000 by the Quebec Human Rights Tribunal for making jokes about a singer with disabilities, has been given leave to appeal.

The Ward case rightly drew support from comedians (and others) who didn’t particularly like the material. David Mitchell, commenting in The Guardian on jokes like Ward’s, said: “If we take ‘OK’ to mean ‘nice’, ‘polite’, ‘admirable’ or ‘kind’, then it isn’t. But if, by OK, we simply mean ‘legal’, then of course it’s OK. And quite right too.”

Offence depends heavily on context. Anybody who tells jokes for a living can easily imagine finding that an offensive gag is now a civil or even criminal offence. Collective self-interest alone should be (and usually is) enough to make comedians hold the line that legally, at least, anything goes in comedy.

This is not to say that one joke is as good as another. As writers, performers and audience members, we should discriminate between good and bad work. But this is a matter of quality, not morality. Lazy comedy presses the obvious buttons of the target audience. That can mean “back door” jokes about gay sex, or making fun of Donald Trump.

But you can hit the same targets without being lazy. Comedian Trevor Noah, host of the Daily Show, attacked both Donald Trump and the response to “Pussygate” with material that mocks those outraged by his use of “the P-word”, instead of by sexual assault. By ending his routine with the phrase “no pussy for me,” Noah will have offended those people all over again. That’s his point: it’s not about the word.

Although I prefer comedy that challenges the audience, rudely or gently, it’s no more possible to draw a line around acceptable approaches than around permitted subject matter. Again, it’s all about context. The same joke can shake one audience’s core beliefs, but reinforce another’s smug certainties.

So there should be no holds barred in comedy, nothing forbidden and nothing out of bounds. Leave it to the judgment of writers, performers and the audience. Especially the audience, because any kind of censorship is depriving them of their right to be offended.

Nobody has a right not to be offended. Certainly not a right enforced on their behalf by those in authority. How can anyone feel at once so vulnerable about being able to withstand unpleasant humour, and yet so confident in their capacity to draw the line of social acceptability?

It’s an absurd position, that only makes sense if each individual’s feelings are the supreme arbiter of moral value. And if each of us can insist that the law, or collective social censure, forbid the hurting of our feelings, there will soon be nothing left in shared culture but the blandest, safest, most anodyne pap.

We do all have the right to express our feelings of anger and disgust if we don’t like a joke. We have the right to leave the venue or switch the channel, to speak or write our own views, or simply to withhold our laughter which, for a comedian, is akin to withholding oxygen.

Though we should ask ourselves what provokes these feelings in us. Is it targetting of the weak, asking us to become vicarious bullies? Is it an unsettling of our ideas about ourselves, as we laugh at things we never thought we’d find funny? Or is it that we don’t think other people should listen to this, in case weaker minds than ours are poisoned by words or images?

If it’s the first, that you’re simply not amused by “punching down,” (or gratuitous lewdness, or whatever) don’t laugh. Be unamused. Like a tango, comedy takes at least two, and if one side of the partnership is not in the mood, comedy will quickly go flaccid.

If you don’t like being unsettled, that’s also fine. Not everybody goes to comedy to be made to think, just as not everybody goes to the opera for the thrilling discords of the latest Harrison Birtwhistle. Pick a different comedian next time. But it’s not up to you to prevent others subjecting their fondly-held ideas to the test of mockery, or of sudden shifts of perspective.

If your objection is that other people may be swayed by a joke to views you don’t like, you may be over-estimating the power of comedy or underestimating your fellow humans’ capacity to think for themselves. Or both. Either way, the only word for trying to prevent somebody else from seeing or hearing something is censorship.

As somebody who still writes and performs comedy, I’m almost flattered that anybody thinks it has that much power. It’s a long time since I was worthy of censure or censorship. So long that the offending material was about the aftermath of Diana’s tragic death in a car crash. These days the most controversial material I do involves a graph of the medical benefits of moderate drinking (you’d be surprised how provocative that can be to the right audience).

When I do shows, I hope people leave both amused and provoked to think afresh. As a writer and performer, I craft each line with that in mind.

But as a human being, I know that my audience arrived in the venue with their own thoughts, leave with their own thoughts, and engage with my ideas on their own terms, if at all. So politically, more important than anything I can say or show to them in that venue is the fact that they are free to decide for themselves what to see, what to hear, and what to think.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1485724697354-3cadb031-9134-7″ taxonomies=”8826″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Apr 2016 | Awards, mobile

Indonesian comedian Sakdiyah Ma’ruf, a nominee for the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for arts, was born to conservative Muslim family in Java and went on to become one of very few female stand-up comedians in the country to appear on national TV.

British comedian Shazia Mirza, the host of this year’s awards, talks to her about tackling no-go subjects, trying to win family approval, and how the stand-up scene is growing for women in Indonesia.

Sakdiyah Ma’ruf (left) and Shazia Mirza (right)

SHAZIA: Have your parents come to watch you do stand-up?

SAKDIYAH: My parents came to one of my shows once. It was in 2012 in one of the biggest theatres in Jakarta. I invited them to the show because it was held in a “dignified” building. I wanted to help my parents, and especially my dad, see that I was doing a “dignified” job.

I was very nervous. It was a full house. But I didn’t care whether the audience liked me or not, as long as I could get at least silent approval from my dad.

Since the show, my dad has supported me in my career as a comedian – not fully perhaps – but from this moment on, he knew that stand-up was something I did and would continue to do – in addition to the other “real jobs” I have.

I remember my parents saying they were pretty nervous about how the audience would respond to me. Perhaps my dad thought he could accept what I was doing if I gained approval from at least half of the audience.

The truth is that it isn’t always easy to get out of the house to perform. In June 2015 I was invited to open for a good friend of mine who is one of the biggest stand-up comics in Indonesia. He called me in April for the gig and it took me almost a month just to craft the right sentence to ask for my dad’s permission to perform.

SHAZIA: Do you say exactly what you want to? Or do you think: “No I can’t say that, people might get upset”

SAKDIYAH: The truth is that I rarely say exactly what I want to. I mean, can you imagine expressing all those voices in your head to the audience?

I say what I believe in; what I have experienced; what I am concerned about; what I like; what I don’t like; what I’m angry about… For me, comedy is always about telling the truth. You can’t be genuinely funny without being completely honest with yourself and your audience.

But I do self-censor, I self-censor all the time! I’m not afraid to talk about taboo topics like religion, race relation, a bit of sex etc – but only if it helps me to be honest with myself and my audience to be honest with themselves. I make sure I craft my jokes on these topics in a way that is truly funny; otherwise I’ll just sound like another girl complaining about how unfair life is.

I also make sure I’m being fair. I fact-check before I talk about something, so that I don’t just make things worse.

SHAZIA: Are you the only woman in Indonesia doing stand-up?

SAKDIYAH: No, of course not. I was the first, but the number is now growing. Every year there are new female stand-up comics performing on TV or participating in competitions.

SHAZIA: Do you feel pressure to talk about “heavy” subjects, like Islamophobia and terrorism, in your comedy? Or do you prefer to talk about lighter things sometimes – like shopping, dating, going on holidays.

SAKDIYAH: I want to talk about the issues that matter to me, things I can relate to, things that are part of who I am and what I have experienced.

I love talking about Muslims and the way they practice and interpret their religion. I talk about Islamophobia, violence towards women, the idea and construction of femininity and masculinity, my ethnicity.

Yeah, sometimes I feel such pressure to talk about “heavy” topics, but for what it’s worth, I think there is no such thing as a “light” topic in comedy. With a great comedian, even jokes about a refrigerator can bring new insights on humanity.

And I guess this is what is so beautiful about comedy: it helps us get to know who we are who others are as well. Every individual has multiple identities. I have been perceived as this Muslim girl fighting against fundamentalism through her comedy. While this is true, I do not want to just be seen as some kind of a “comedy jihadist” fighting against fundamentalists. I have layers to my identity, just like everybody else.

SHAZIA: Do you receive letters and emails from people who have seen your performances? What kind of things do they say? What do women say?

SAKDIYAH: Yes, I do. A woman once asked me whether I am a “true” Muslim. Perhaps she considered my jokes too daring or inappropriate for a Muslim woman to tell. She asked me all these questions about whether I really wear the hijab every day and whether I pray five times a day.

I like getting these kinds of responses. I feel like these people genuinely care about me or at least about Muslim women in general.

21 Jul 2015 | Magazine, mobile

Whenever I’m trying to fill an hour of stand-up for the Edinburgh Festival, the last thing I wonder is, “Jeez, will this set land me a spot on television?” The reasons are twofold: first, I do what makes me laugh, otherwise I get bored; second, I’ve done stand-up on television and it ain’t the apex of my career. Television producers and editors seem to have an uncanny knack for siphoning the humour out of just about anything, especially the royals, and particularly the pretty, dead ones.

Yet television comedy is held in some oddly high regard as a move up for a comic. I guess that’s because if you can’t get a TV profile going, your live shows in the provinces don’t sell very well. Why should someone in, say, Leeds, come and see you at the Varieties if you aren’t good enough to be on Les Dawson?

But to be on Les, or any television programme, your set must be “clean”. Which means few or no dirty words. Misogyny within social norms, fine, but save the word “cunt” for the wife beatings, mate. That’s right. No “cunts”, although the halls of the BBC are teeming with them. Which is sad, since “cunt” is plainly the most versatile word in the English language. It’s a verb, a noun, an adjective, and it’s really the last word on earth that, no matter how it’s used, makes my mother angry. One is also discouraged from using the word “fuck” on television, particularly as a verb. Particularly if you’re gay.

See, as an out cocksucker, there are lots of things I can get away with on stage but, on television, I’m already perceived as dangerous. TV companies treat me, in rehearsal for a taping, as though I’m retarded or a child or, worse yet, American. “Please be nice, Mr Capurro. You want the people watching to like you, don’t you? Good. We wouldn’t want everyone to think that you’re naughty, would we?”

Then they go through the litany of words I’m not supposed to use. When the show is edited and televised, other comics’ “fucks” are left in. Mine are removed. After all, being gay is dirty enough. Do I have to be dirtier with my dirty mouth?

I’m not really complaining. I’ve learned to manoeuvre my way throughout television. I can play the spiky-but-warm, take-the-cock-out-of-my-mouth-and-press-the-tongueto-my-cheek game with squeamishly positive results. Usually. But in Australia, during the taping of a “Gala” to honour a comedy festival in Melbourne, the director had a grand-mal seizure when I described Jesus as a “queerwannabe”. I saw papers fly up over the heads of a stunned, strangely silent audience. Later I found out it was the director’s script. Apparently they found him after the show, huddled in a corner, crying like a recently incarcerated prisoner who’d just taken his first “shower”.

He was afraid I’d pollute minds, I suppose. At least that’s what he told his assistant. So now, TV is promoting itself as a politically correct barometer? A sort of big-eyed nanny looking out for our sensitive sensibilities? In the six years that I’ve been performing in the UK, I’ve seen political correctness catch on like an insidious disease, like a penchant for black, like the need to oppress. Comics use the term to describe their own acts during TV meetings, and everyone around the table nods in appreciation and approval. Or are they choking? I can never tell with TV people.

Maybe they’re suffocating under a pillow of their own stupidity, since no one really understands the meaning behind political correctness, the arch, high-browed stance it panders to. The phrase was coined as a reaction to racism in the US, to respond with a sort of kindness that had been stifled when hippies disappeared from the US landscape. PC took the place of sympathy which has, since Reaganomics, had a negative, sort of “girlie” tone to it that few US politicians, especially those who served in ‘Nam, can tolerate. Being politically correct makes the user feel more in control and smarter, because they can manipulate a conversation by knowing the proper term to describe, say, an American Indian.

‘They’re actually indigenous peoples now,’ a talk-show host in

San Francisco told me while on air recently. ‘The word Indian is

too marginal.’

‘But where are they indigenous to?’

‘Well, here of course.’

‘They’re from San Francisco?’

‘No. I mean, yes. My boss’ — we were discussing his producer, Sam —

‘was born and raised here, but his parents are Cherokee from Kansas. Or

was it his grandparents?’

‘My grandfather is Italian, from Italy. What does that make me?’

‘Good in bed.’

Indigenous, tribal, quasi or semi. All these words are used to describe, politely, “the truth”. But, strangely enough, the truth is camouflaged. The white user pretends to understand the strife of the minorities, their emotional ups and downs, their need for acceptance and understanding, when all the minorities require is fair pay. I’ve never met a struggling Costa Rican labourer who was concerned that he be called a “Latino” as opposed to a “Hispanic”. He just wants to feed his family. Actually, I’ve never met a struggling Costa Rican, period. But that’s because I’m one of the annoying middle class who keep a distance from anyone who’s not like them, but who also has the time and just enough of an education to make up words and worry about who gets called what.

To the targets, the people we’re trying to protect – the downtrodden, the homeless, the forgotten – we must appear naive and bored, like nuns. It’s a lesson in tolerance that’s become intolerant. As if to say: “If you don’t think this way, if you don’t think that a black person from Bristol is better off being called Anglo-African, you’re not only wrong, you’re evil!” It’s pure fascism, plain and simple. It’s as if Guardian readers had unleashed their consciousness on everybody else, and so it’s naughty to make jokes about blacks, unless you’re black, and bad to make fun of fat people, if you’re not fat, etc. Suddenly, everyone is tiptoeing around everyone else, frightened they’ll be labelled racist because they use the word “Jew” in a punchline. Or horrified someone will think them misogynist because they think women deal better with stress.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

14 July: The power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe by Samm Farai Monro | 17 July: How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson | 21 July: Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro | 24 July: They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon | 28 July: Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera | Student reading lists: Comedy and censorship

Somehow we’ve forgotten that it’s all in how you say it. To read a brilliant stand-up comic’s act is pedantic, but to see it performed is breathtaking. That’s because what we say might be clever, but the way we arrange and self-analyse and present is where the fun comes in. Same with all those words we use. They’re not “racist” or “dangerous” by definition.

Speaking of definitions, let’s talk about the word “gay”. Lots of people I meet are concerned about what I should be called. Is it gay, which pleases the press, or queer, which pleases the hetero hip, since they think gays are trying to reclaim that word? The fact is that all those words are straight-created straight identifiers. Gay is a heterosexual concept. It’s a man who looks like a model, dresses like a model and has the brain of a model. He has disposable income, he loves to travel, and he adores – thinks he sometimes is – Madonna. He’s a teenage girl really and straights love objectifying him the -way they do teenage girls. Or the way they do infants. Try watching a diaper commercial with the sound off. It’s like porn. You’ll think you’re in a bar in Amsterdam.

I’m about as comfortable with the word “gay” as I am with kiddy porn. I’d prefer to be called a comic. Not a gay comic. Not a queer comic. Not even a gay, queer comic, or a fierce comic, or an alternative comic. It’s just the mainstream trying to pigeonhole me, trying to say, OK, he’s gay, so it’s OK to laugh at his stuff about gays. Which is why, partially, in my act, I make fun of the Holocaust by saying “Holocaust, schmolocaust, can’t they whine about something else?”

The line is meant to be ambiguous, initially. It’s meant to start big, and then the actual subject gets small, as I discuss ignorance about the pink triangle as a symbol of oppression, which has since been turned into a fashion accessory. Like the red ribbon, it makes the PC brigade feel like they’ve done their part to ease hatred in the world by adorning their lapel with a pin. When pressed, they’re not even sure what oppression they’re curing, or why they should cure oppression, or how they’re oppressed.

But if you make fun of that triangle, or this Queen Mum, or that dead Princess, suddenly you’re — why mince — I’m the bad guy. I’ve broken away from the pack. I’m not acting like a good little queer should. I’m not being silent about issues that don’t concern a modern gay man, like hair-dos and don’ts. I’m being aggressive, I’m on to. And those straights, those in charge, the folks looking after “my minority group”, don’t like rolling over.

Nor are some cocksucking idiots happy about being bottom-feeders either. Which is why I come out against abortion in my act, and in support of the death penalty since, in the US at least, the two go hand in manicured hand. There I go, losing my last supporters: young women and single gay men. How can I say: “If you wanna talk Holocaust, how about abortion, ladies? 50 million. Can you maybe keep your legs together?”

That is truly evil. No, not really evil. Just wrong. Why? Particularly when I’m only opposed to abortion as a contraceptive device. Who decides what I can and cannot say? Isn’t it the people that aren’t listening? If I’ve got a good joke about it, a well-thought-out attack and a point to make, why is it bad? Why is the world dumbing down almost as fast as Woody Allen’s films? Why does it bother me? Why not just do my same old weenie jokes, keep playing the clubs and sleep with closeted straight comics? Just doing those three things – particularly the last – would keep me very busy and distracted, which is what “life” is all about.

But I imagine that when people go for a night out, they wanna see something different. It’s a big deal finding a babysitter, getting a cab, grabbing a bite and sitting your tired ass into a pricey seat to hear some faggot rattle on for an hour. So I try to offer them a unique perspective. One that might seem overwrought, desperate, or strangely effortless, but one that might make them look at, say, an Elton John photo just a bit differently next time

Look, it’s not my job to find anyone’s comfort zones. I don’t give a shit what people like, or think they like, or want to like. I’m not a revolutionary. I’m just a joke writer with an hour to kill, who wants to elevate the level of intelligence in my act to at least that of the audience.

If in doing that, I get a beer thrown at me or I lose a “friend” (read: jealous comic) then so be it. In the meantime, I’ll keep fending off my growing array of fans that are sick and tired of being lied to and patronised.

Gosh, get her! I mean me. Get me, sounding all holier than, well, everybody. Strangely enough, the more I find my voice on stage, the more serious comedy becomes for me. Maybe I should go back to telling those “Americans are so silly” jokes before I lose my mind, and throw all my papers up in the air.

Scott Capurro is a San Francisco-based stand-up whose performance at the

Edinburgh Fringe in August ended in uproar after he ‘made jokes’ about the

Holocaust. His book, Fowl Play, was published by Headline in September

1999

This article is from the November/December 2000 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

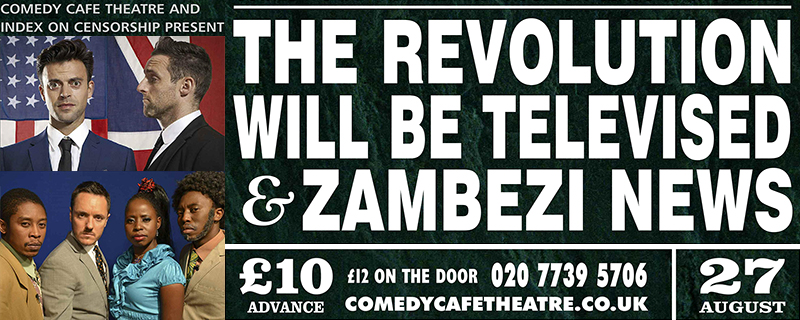

30 Jan 2015 | Events, mobile

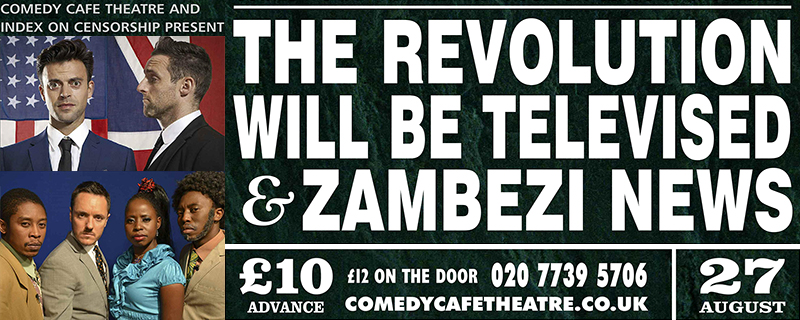

The London Irish Comedy Festival is hosting a free event about comedy and censorship.

Controversy has always surrounded the comedy industry, from stand-up to sitcom to satire. During the discussion, ethics, censorship, freedom of expression and taste will be explored by special guest panellists and the audience.

- What makes us sometimes laugh at the very worst of human nature?

- Is comedy a natural and positive way of coping with horror?

- When is a joke just too offensive to use?

- When exactly is “too soon”?

- What’s off limits?

- Is every aspect of life fair game?

Join the London Irish Comedy Festival to grapple with these and many other questions in a provocative and interactive event.

PANELLISTS INCLUDE

Steve Moore, Entrepreneur, Campaigner and Facilitator

Jodie Ginsberg, Chief Executive, Index on Censorship

Eddie Doyle, Head of Comedy, Talent Development & Music, RTÉ

Austin Harney, Chair, Campaign for the Rights and Actions of Irish Communities

Gráinne Maguire, stand-up comedian, comedy writer and columnist

WHERE: Comedy Café Theatre, 68 Rivington Street, Shoreditch, EC2A 3AY

WHEN: Thursday 19th February 2015 – 8:00pm

TICKETS: Free but must be reserved – available here