Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

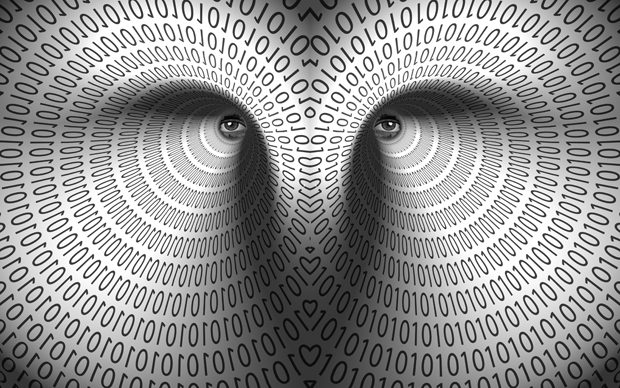

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) filed an application on Friday with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg challenging current UK legislation on mass surveillance and its threat to journalism.

Lawyers Gavin Millar QC at Doughty Street Chambers, Conor McCarthy at Monckton Chambers and Rosa Curling at Leigh Day solicitors have been assisting the BIJ with its investigation. The group argues that UK legislation imposes constraints on journalistic free expression and does not offer enough protection for journalists’ sources, therefore it is in breach of Articles 8 and 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR).

Information uncovered by American whistleblower Edward Snowden appears to highlight how developments in mass surveillance could pose a major threat to the process of journalism. Rules for the interception of data are set out in the Regulation of Investigative Powers Act (RIPA), however, this act does not offer enough controls or checks for external communications. Therefore, any information exchanged through services such as Gmail, Google Docs and Dropbox may not offer the level of confidentiality expected, the group wrote in their application to the ECHR.

It is not only communications which may be scrutinised by the government or secret services; they also have access to metadata, which is the data generated as you use technology. It includes information such as the date and time of phone calls and where emails are sent from. Metadata can be linked to sophisticated computer programs which can enable the user to collate masses of information, building an intricate picture of an individual or organisation’s movements, contacts, sources and lines of enquiry.

According to BIJ, the main implication of unregulated mass surveillance is that journalists can no longer offer anonymity to their sources, or assume that their work is confidential until publication.

This is further compounded by the number of the situations where it is deemed appropriate for surveillance techniques to be enlisted are vaguely defined within the law. It states that data can be intercepted where it is believed that the security or economic interests of the state are involved, meaning investigative journalists especially have to be cautious when covering topics which may be of interest to the government and the intelligence services.

Currently, the BIJ believes the only way in which journalists can be sure they are protected against mass surveillance is to do all of their communications in person, without the use of electronic devices – something which is often impossible, especially if sources are based outside of the UK.

However, under the ECHR journalists should be able to expect protection, the BIJ asserts. At the very least, the group said, this application will spark high-level debate within the government about how journalism and freedom of expression can be protected when governments are using advanced surveillance.

The BIJ says: “In the long term we would like to see proper regulatory control and scrutiny of how the intelligence services use mass surveillance to ensure these techniques and technologies are not being used to hamper legitimate journalistic investigation and inquiry.”

This article was posted on Sept 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Across the world, debates around freedom of expression have intensified, in part due to people’s increased participation because of the many avenues communication available today. Confidence seems to follow connectivity. But think of the people who remain disconnected — excluded from national and international discourse — because of the lack of wires and signals. As tempting it is to believe that the whole world is connected, the truth is very different, especially in developing countries such as India. The numbers speak for themselves.