20 Nov 2015 | Croatia, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

Croatian prime minister Zoran Milanović. Original image by SDP Hrvatske

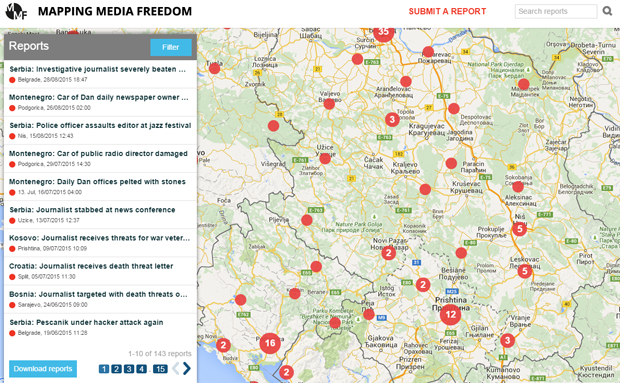

A worrying escalation of attacks on the media in Croatia has been recorded by the Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project in the last three months. Since 1 September there have been 13 attacks, compared with 3 in the same period last year.

In August, we reported an increase in media violations in Croatia. Deaths, physical assaults and intimidation had been plaguing the Croatian media for months. Increasing violence is still undermining media freedom in Croatia.

Hannah Machlin, Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project officer, said: “The increasing amount of violence against Croatian journalists is quite alarming. In reaction to the migrant crisis, there’s been a particularly high number of cases on the Hungarian/Croatia border.”

The Croatian constitution guarantees freedom of expression and the press, and “these rights are generally respected in practice”. Freedom House does, however, acknowledge that journalists face political pressure, intimidation and the “occasional” attack. According to Freedom House, Croatia has been a “free” country for some years.

Below, Index on Censorship details some of the worst cases from Croatia since September.

Overall attacks, including violence, intimidation, loss of employment and censorship of work

1. Media workers assaulted by police at Serbian border

In early October, Croatia opened its border with Serbia, easing one of the main areas for congestion for refugees trying to make their way north. On 19 October, Mapping Media Freedom recorded that media workers were harassed and assaulted by Croatian police on the border near the Bapska-Berkasovo crossing. Regional N1 television reported that the Croatian police had also confiscated the journalists’ equipment.

“When they moved against me, I shouted that I was an AFP photojournalist and that their colleagues had checked my ID this morning,” Andreja Isakovic told N1. “They asked me to hand over the cards. One of them ran towards me, caught up with me and threw me into the mud. They took away my cameras in a savage manner and threw them into an orchard on the Croatian side, so I could not reach them. They did the same to my colleague from England.”

2. Greek journalists attacked by masked assailants

In mid-October, two Greek journalists, George Stasinopoulos and Dionisis Verveles, were attacked by unidentified individuals while walking near a sporting event in Zagreb. Two men wearing face masks stopped the journalists on a street, asking them to identify themselves and their origin. When the two colleagues attempted to run away, they were attacked.

One journalist was beaten and the other was threatened by one of the assailants who was brandishing a knife. When the journalists began shouting that they were members of the press, the attackers fled the scene.

3. Prime minister’s father threatens journalist

Velimir Bujanec, host of the controversial TV show Bujica, was verbally assaulted by Stipe Milanović, father of Croatian prime minister, Zoran Milanović. Gordan Malic, a local freelance investigative journalist based in Croatia, was also threatened. Around noon on 3 October in a coffee bar in the center of Zagreb, Stipe Milanović allegedly said that “Bujanec and Gordan Malic should be beaten up”. There were three witnesses to his comment.

Bujanec reported to the media and posted it on Facebook. After speaking with his lawyer, he also reported the incident to the police and is now reportedly pressing charges against Milanović for verbal assaults and threats.

4. Journalist’s car tires slashed

Suzana Trninic is a journalist with the Serbian television broadcaster B92. On 24 September, while travelling to a media festival in Rovinj with Belgrade license plates on her car, she and her team stopped for coffee at a petrol station in Grobnik. When they returned, one of the car’s tires had been slashed.

There was visible sticker press on the vehicle, Trninic said. She did not want to report the incident to the police and media on the day as she did not want to distract from the ongoing border crisis between Serbia and Croatia.

Trninic believes the incident is connected with her being a Serbian journalist.

5. Asylum seeker attacks TV crew

“I’ll kill you!” yelled the assailant as a stone hit the cameraman. Click image for video. Credit: Večernji.hr

On Thursday 17 September 2015, an asylum seeker from Kosovo began shouting threats and then threw a brick at the TV Mreza crew reporting at Hotel Porin. One cameraman was injured. The assailant was immediately restrained by other journalists until riot police arrived and detained him.

Hotel Porin is both a reception and registration centre where asylum applications are completed, including fingerprinting and medical examinations. As Croatian media has reported, almost all refugees are polite and grateful and all have the right to leave the hotel and walk around Dugavama.

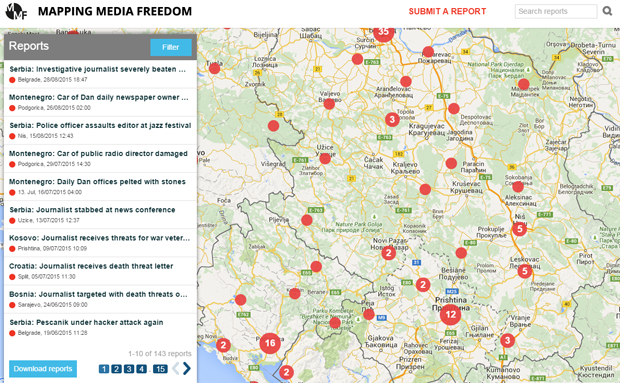

Details of attacks on the media across Europe can be found at Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom website. Reports to the map are crowdsourced and then fact-checked by the Index team.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

18 Sep 2015 | Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Montenegro, News, Serbia

“Media has a significant role in the theatre of the absurd,” a participant in a conference on the security and protection of journalists in western Balkan countries claimed.

Media workers and representatives from journalists’ associations in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro joined representatives of international organisations in Sarajevo in June 2015 to debate key issues facing the media in the region: attacks on journalists, impunity, the effectiveness of the legal system and institutional mechanisms to create a safe environment to work in.

Conference participants said media freedom is deteriorating and assigned responsibility for the decline on governments in the region, local media ownership and, especially, international institutions and organisations.

Goran Miletic, programme director for the western Balkans at Civil Rights Defenders, an NGO working in the area, said that in 2004 some of the international organisations decided to withdraw funding from local media to focus on other projects. Miletic said that reduced level of funding for media was a lost opportunity to prevent human rights abuses and further democratise the region.

International funding is vital to professionalising the media, which cannot rely on local government support. “If we analyse research on what people think of human rights defenders or journalists, they are often characterised as spies, foreign mercenaries, or enemies of the state,” said Miletic.

A lack of media plurality and news illiteracy were identified as concerns that have had a detrimental effect on the advancement of press freedom and professionalism in the region.

“Media freedom is once again one of the key challenges for the region,” said Andy McGuffie, head of the communication office of the Delegation of the European Union to Bosnia and Herzegovina and a European Union Special Representative.

Presidents of journalists’ associations focused on attacks on journalists and the effectiveness of the legal system and institutional components. Addressing the current situation in Croatia, Zdenko Duka, then president of the Croatian Journalists’ Association, underlined that “fortunately, [in recent months], there have not been too many physical assaults. Comparing assaults and threats against journalists to other countries in the region, the situation in Croatia is better.”

Croatia has a checkered history on media freedom. During the 1990s journalists were widely targeted and were under surveillance by the secret service. In the 2000s, the journalist Ivo Pukanic, was assassinated in a bomb attack at his Zagreb office. Though a court convicted six men for the murder, the person who ordered the crime has not been brought to justice.

Duka emphasised two 2014 physical assaults: an incident in Rijeka in which football club officials attacked a journalist and a photographer and the brutal attack on journalist Domagoj Margetic who was assaulted by several people near his home in Zagreb. Margetic sustained head injuries as a result of the attack, for which he received medical treatment.

Sanja Mikleusevic-Pavic, a journalist from Zagreb, agreed with Duka. “Croatia is in a much better situation than other countries,” she said. Key reasons for this include the Trade Union and the Journalists’ Association, which are very well organised and powerful, but most of all, the key role played by the public broadcaster HRT. “HRT is a strong, independent and professional public broadcaster,” said Mikleusevic-Pavic.

From her point of view, the main threat to independence and professionalism are pressures from tycoons and politicians, which, in her experience, are significant. The case of Croatian TV broadcaster RTL, which was found guilty of slander for airing a live show during which Croatian Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic accused Zagreb Mayor Milan Bandic of corruption, sets a negative precedent, particularly because another TV station that aired the same statement was not charged. As punishment, RTL has been ordered to pay 6,500 euros to the mayor.

Croatia’s new criminal code presents another obstacle to media freedom. It includes Article 148, introduced in 2013, which establishes an offence of “humiliation”, “shaming” or “vilification”. Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso said the article would allow judges to sentence a journalist if the information published is not considered being in the public interest and “for the court, it is of little importance that the information is correct – it is enough for the principal to state that he felt humbled by the publication of the news.”

In April 2014, Jutarnji List journalist Slavica Lukic became the first Croatian journalist to be prosecuted under the article. She was found guilty of vilification. Lukic reported that a company had economic problems despite the substantial public funding it received. The company stated it felt “humiliated” and the judge fined her 4,000 Euros.

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, said in a letter to the Croatian officials that the current legal definitions of “insult” and “shaming” are “vague, open to individual interpretation and, thus, prone to arbitrary application.”

Duka said that there are more than 40 criminal insult cases pending against journalists in the country and this is clear evidence that “truth can be punishable.” Furthermore, he believes judges are not well prepared for defamation, slander and libel cases. Defamation in Croatia has not been decriminalised as it has been in Montenegro, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“The situation in Serbia is alarming. As long as there is a brutal assault on journalists, we cannot talk about freedom of speech and media freedom,” Vukasin Obradovic, president of the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia (NUNS), said in a speech at the conference.

From 2008 to 2014, Serbia has seen a total of 365 physical and verbal assaults, intimidation and attacks on the property of media professionals. Since May 2014 alone, Index’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom project has received over 48 reports of violations against Serbian media, including attacks to property, intimidation and physical violence.

In his talk, Obradovic described several incidents to illustrate the media situation in Serbia. On 14 April 2007 a bomb exploded outside the apartment of journalist Dejan Anastasijevic. No one was injured. In a statement to international media, Anastasijevic said: “It was just before 3 am on Saturday when a hand grenade went off outside the bedroom window of my Belgrade apartment, filling the room with smoke and shards of glass, leaving shrapnel holes on the ceiling and walls — some only inches above the bed. Despite the damage, we were lucky: When the police arrived, they found a second unexploded grenade on the sidewalk nearby.”

Anastasijevic was targeted because of his investigative reporting on crimes in the former Yugoslavia and criminal syndicates in Serbia, local media reported. The most recent attack followed Anastasijevic’s criticism of a lenient verdict for members of Serb paramilitaries called “Scorpions,” journalists associations said. The case has still not been resolved.

Obradovic emphasised that attacks on journalists in Belgrade often get more attention than violations that take place outside the capital.

Vladimir Mitric, a journalist from the town of Loznica, has been under police protection since October 2005 after being subjected to a brutal assault. He was attacked as he entered his apartment and struck with a blunt instrument from behind several times. He ended up with a broken hand and was very badly bruised all over his body. He is disabled as a result of that attack.

“I live under police protection that I was granted by court, not police, at my request, which is important,” said Mitric in an interview with SEEMO. A former police officer was identified as the attacker and was sentenced to six months in jail by the Loznica Basic Court. The Belgrade Court of Appeal later doubled the sentence.

However, a few months after the trial, Tomislav Nikolic, the president of Serbia, granted amnesty to the attacker and the remainder of his sentence was vacated. Threats against Mitric continue despite 24-hour police protection. Human Rights Watch reported: “The person making the threats was accompanied by a police officer who had been responsible for Mitric’s protection. The person making the threats was charged with minor offences in September, but at this writing the police officer had not been disciplined.”

Sladjana Novosel, a journalist from Novi Pazar, was targeted three times between September 2010 and March 2013. Novosel was subjected to verbal attacks, shaming and bullying. Police have, so far, failed to pursue investigations of these threats.

In another incident, Davor Pasalic, the editor-in-chief of FoNet, was attacked twice early in the morning of 3 July 2014 as he made his way home from his office. The two attacks left him with cuts and bruises, and four of his teeth were broken or knocked out. After seven months of investigation and zero progress, Pasalic sarcastically said that his case is “no big deal.” But he added that the assault has had no impact on his work.

Obradovic finished his talk by saying that “the impunity and recklessness of institutions obviously encourage attacks.”

Branislava Opranovic, member of the executive board of the Independent Journalists’ Association of Vojvodina (NDNV), focused on economic issues and ownership transparency in the media. She described the lack of ownership transparency in the media, sharing her personal experience. “I have been working for the daily Dnevnik for years and years, but still don’t know who the owner of the newspaper is.” She also mentioned other cases, including one where a man in his twenties wanted to buy nine media outlets in Vojvodina, or the episode where her coworkers were waiting patiently in a line to collect bonuses of 5 Euros despite having not received their salaries.

Though Bosnia and Herzegovina was the first country from the region to decriminalise defamation, in 1999, the situation is no better than in Serbia. Borka Rudic, Secretary General of the BH Journalists Association, said: “The raid of the Klix.ba offices in late December 2014 just proves this conclusion.”

In that incident, police entered and searched Klix.ba’s Sarajevo offices for a recording of a phone call in which the Republika Srpska Prime Minister Željka Cvijanović talks about “buying off” politicians. Local media reported that police were copying material from the newsroom’s computers. The police also seized computers, documents, notes and other items from the offices, according to media reports.

Despite positive developments in the law over the past 15 years, the situation has shown little improvement, as institutions are failing to properly implement new legislation, meaning protection on journalists is weak. Between 2006 and 2014, there have been approximately 400 registered cases of media rights violations, including 40 physical assaults and 17 death threats.

Bosnian journalists use a name and shame strategy, in which the identity of every person who threatens or attacks a journalist is publicised. Rudic said that the most serious incident was the attack of Professor Slavo Kukic, a prominent writer and columnist, who was severely beaten with a baseball bat in his office at the University of Mostar, on 23 June 2014.

Marko, a journalist present at the event, shared his and a colleague’s personal experiences. While working for a public broadcaster they were both victims of constant harassment by one of their deputy editors, receiving no support from senior editors or directors. This resulted in them both being admitted to a psychiatric hospital for mental health issues.

Montenegrin TV host and journalist, Darko Ivanovic, told how one of his country’s prominent politicians stated: “it is customary law to hit journalists,” when asked why he slapped a journalist.

Over the last few years Ivanovic has had his car vandalised on a number of occasions, though only one incident resulted in the arrest of a suspect, who admitted the vandalism. However, when interviewed by Ivanovic, the suspect admitted that the police gave him 5 Euros so he confessed to the crime. “There is always someone found guilty, but usually they’re not the real perpetrators. And this puts into the question the effectiveness of the system,” Ivanovic said.

Marijana Camovic, President of the Trade Union of Media of Montenegro, said at the conference “the mindset of local politicians is that for them it is impossible that a journalist could be impartial and professional.”

Tabloids in Montenegro are used for smear campaigns. Civil rights activist Vanja Calovic became the victim of just such a campaign by Informer, a daily newspaper. The tabloid’s mid-June attack against the head of the MANS NGO began with the release of a video recording that, according to the paper, proved that Calovic was “an animal abuser” and alleged that she had sexual relations with her dogs.

The NGO Human Rights Action (HRA) highlighted the perilous state of journalism in its report, “Prosecution of Attacks on Journalists in Montenegro”. The HRA outlined 30 cases of threats, violence and assassinations of journalists as well as attacks on media property between May 2004 and January 2014. “Most of these attacks have not been clarified to date. In most cases certain patterns can be observed, for example: victims are the media or individuals willing to criticise the government or organised crime,” the report said.

One-third of all incidents happened in the the last year, which to the HRA shows the atmosphere of impunity is escalating. “Such an atmosphere of impunity threatens journalists in particular, who are often victims of unresolved attacks. If the state treats these attacks passively, it becomes responsible for the suppression of freedom of speech, the rule of law and democracy.”

The assassination of Editor-in-chief of the Daily Dan, Dusko Jovanovic, who was killed in a drive-by shooting on the evening of 27 May 2004, has not been solved nine years later. Damir Mandic, the only defendant in the recent trial, claims he is innocent and accused the police of planting evidence, Balkan Insight reported. Mandic said he was in prison for 10 years although he was innocent, and his human rights had been violated. He remains the only perpetrator to be convicted.

Seven years after the brutal attack that nearly took the life of journalist Tufik Softic, Montenegrin police detained two men suspected of involvement in his attempted murder. For media unions and observers, the detentions were long overdue, but emblematic of the atmosphere of impunity in Montenegro. In November 2007, Softic was brutally beaten in front of his home by two hooded assailants wielding baseball bats. Then in August 2013, an explosive device was thrown into the yard of his family home. The journalist has been provided with constant police security since February 2014.

Besides this atmosphere of impunity that threatens journalists, Camovic spoke of other phenomena. Approximately 80 per cent of all active media workers in Montenegro are not members of any journalist’s association. When asked why they’re not active in the organisations, they had no answer.

In summing up the situation, Ivanovic said that states and political parties deliberately tolerate grey or criminal activities of media owners so they can control them easily.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

28 Aug 2015 | Croatia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

Sasa Lekovic at a Mediacentar Sarajevo event in 2013 (Photo: Mediacentar Sarajevo)

Over the past few months, death threats, physical assaults and intimidation have plagued the Croatian media. This drastic deterioration of media freedom is recorded through Index’s Mapping Media Freedom. In the first year of the campaign — from May 2014 — there were 24 verified incidents in Croatia. Between May and August 2015, there were 14, a 75% rise in verified reports over the same period last year.

This surge in media violations was recently addressed by the Croatian Journalists’ Association (CJA) and an OSCE representative on Freedom of the Media. In a statement published on its website, the CJA highlighted impunity as one of the main issues hindering media freedom throughout the country. “The CJA once again calls on authorities to find and adequately punish those who have threatened and attacked journalists, and to also find those who potentially ordered the attacks.”

The primary concern of the CJA is the long line of unresolved cases surrounding death threats and attacks on journalists. Exactly one year since freelance journalist Domagoj Margetic was brutally beaten in front of his apartment in Zagreb — an attack the Croatian State Prosecution has characterised as attempted murder — information on the attacker and the motive remain absent. Other unresolved cases include that of Antonio Mlikota, graphic editor at the Hrvatski Tjednik newsroom who was bound and threatened with a gun, and Hrvoje Simicevic, a journalist at H-Alter who was physically assaulted. There was also a series of death threats addressed to Katarina Maric Banje, a journalist for Slobodna Dalmancija, Drago Pilsel, editor-in-chief of the Autograf website, and Sasa Lekovic, the president of the CJA, along with others that have not been made public.

In light of the influx of violence, Index spoke to Lekovic, who also received a death threat. Lekovic assumes it was issued as a result of his new role, adding that the CJA makes people who want to control the media very nervous.

Discussing the most prominent threats to media freedom, he emphasised that “journalists in Croatia are under mixed pressure from politicians, media owners, mighty tycoons and organised crime.” Lekovic says this is not particularly new, adding that for almost two decades journalists have been subjected to such threats. “Generally speaking, it isn’t easy to discern the small distinction between these actors, if any.”

Although the primary threat to media freedom is self-censorship, the lack of media integrity is also a problem. “On one hand, we have a number of media outlets, especially web portals, not following any professional standard; they are actually using media freedom against the media,” Lekovic told Index. “On the other hand, we also have some laws that are used against professionals to suspend their right to serve public interest.”

In recent years, the CJA has taken multiple steps towards fostering a more relaxed and professional environment for media workers. Among other measures, they started a project called The Center for Protection of Public Speech.

“We have lawyers who are helping journalists that are in danger, including providing pro bono support and court representation. On the other hand, the CJA is going to work on ideas that better media legislation and their implementation and ones that will improve media literacy and training,” Lekovic says. “It’s all connected and is a long-term job that will not be completed overnight.”

On deteriorating media freedom, Lekovic says the current climate is notably worse than it was two years ago. He explains that “when Croatia was applying to become an EU member, it was under pressure to fulfill EU legislative requirements within the media sphere, but once the country joined the EU, nobody cared about upholding them”.

The OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, Dunja Mijatovic, has called on Croatian authorities to protect critical voices and to investigate the increase in attacks on journalists. Mijatovic wrote to Croatia’s Foreign Minister, Vesna Pusic, calling for swift and transparent investigations.

“As far as I am aware, all these cases remain unresolved,” Mijatovic wrote. “Condemnation coming from the highest level of government should be a clear sign that these acts of intimidation and violence against journalists will not be tolerated.”

Lekovic added that Croatia’s upcoming parliamentary election due by February 2016 is adding to the pressure.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

Related:

• Croatia: 35 reports since May 2014

This article was published at indexoncensorship.org on 28/8/2015

2 Dec 2013 | Croatia, News, Religion and Culture

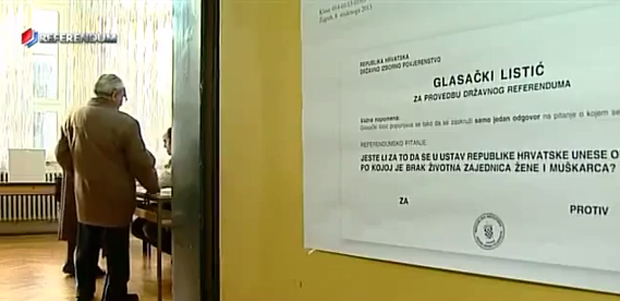

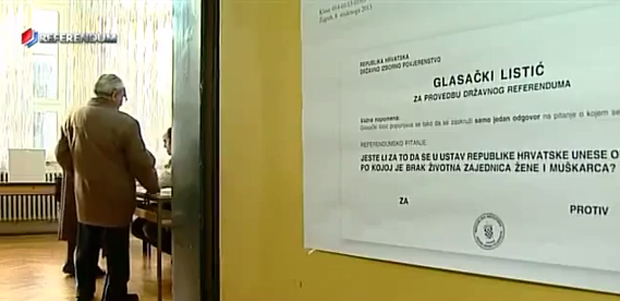

Croatians cast their votes on whether marriage should be constitutionally recognised as being between a man and a woman (Image: Mc Crnjo/YouTube)

Croatia’s voters moved Sunday to amend the country’s constitution to define marriage as being between a man and a woman. The campaign had been orchestrated by the country’s religious institutions. Sixty-five percent of voters supported a change that effectively bars gay marriage.

The campaign used some interesting and controversial tactics. Religious teachers in schools threatened students that they wouldn’t get a passing grade if they did not provide proof of their families’ support for the constitutional change. This was reported by an English language teacher from Split, the second largest city in Croatia, to the inspection body of the Ministry of Education around mid-November.

“If this is the situation in Split I believe it is even worse in smaller towns”, concluded the teacher who did not want to sign her name.

Following this, the media received numerous letters from school teachers confirming that religious teachers around Croatia were blackmailing students to make sure their family members vote “for the protection of the family” — the Catholic Church’s interpretation of the referendum question.

“If the president of the country and other public persons can talk about voting at the referendum why can’t a religious teacher do so?” commented Sabina Marunčić, senior advisor for religious education at the Croatian Education and Teacher Training Agency.

Since the call for a referendum on 8 November, the campaign has been the main topic of discussion in Croatia, despite the country facing a severe economic crisis and an unemployment rate of 20.3 per cent. While Croatian law defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman, this definition does not exist in the constitution. A recent announcement of a new law on same-sex partnerships has caused conservative movements to come together in the initiative “In the Name of Family”. They started spreading fear about gay marriage being legalised, despite the centre-left government showing no intention to do this. A 2003 law on same-sex partnerships has been seen as practically useless because it secures only a few, less important rights, and only after a relationship breaks down.

For weeks all anyone talked about was who will vote “for” and who will vote “against”, in the first national referendum in the Republic of Croatia set up by popular demand. The Social Democratic prime minister Zoran Milanović, President Ivo Josipović and numerous ministers all came forth against introducing the definition into the constitution. A large portion of powerful media was also openly against it. However, public opinion polls showed that 68 per cent of the citizens would vote for the proposal; 26 per cent against.

In the referendum campaign, the Catholic Church have firmly been advocating “for”. It has has a strong influence in the country of 4.29 million, with 86 per cent declaring themselves Catholic according to the latest census, released in 2011. The initiative “In the name of family” which has succeeded in gathering signatures of 740,000 citizens in order to hold a referendum is also linked to the Catholic Church.

“The church did not want to start the initiative for a referendum but it wholeheartedly accepted In the Name of Family, whose numerous members are conservative Catholics close to certain Croatian bishops,” says Hrvoje Crikvenec, editor of the religious portal Križ života (“Cross of Life”).

“However, I believe that the entire organisation and initiative is supported more by politics, that is, a marginal political right-wing party Hrast, than Croatian bishops. They have now become more involved in the campaign in the hope of what would for them be a positive outcome of the referendum, which would ultimately show them as winners.”

The initiative’s leaders do come from the non-parliamentary right-wing party Hrast, as well as conservative associations opposing the introduction of sex education in schools, artificial insemination and abortion. Some of them have been linked to Opus Dei, a secretive Catholic organisation which has been strengthening its presence in Croatia. In the Name of Family and the fight against a possible equal standing of homosexual and heterosexual marriages has provided them with the support of a larger portion of the public.

The Catholic Church has undoubtedly helped the success of a In the Name of Family. Signatures were gathered in front of churches and elsewhere, even in universities. Cardinal Josip Bozanić had written a note instructing priests to encourage believers in masses to attend the referendum and vote for the definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Group prayers for its success were also organised throughout Croatia in the lead up to the vote.

“We can’t blame the bishops for advocating the referendum from the altar because this is a part of the church’s program. They are more entitled do so than to say who to vote for at the elections, which they also do. However, it is inadmissible for religious teachers to influence children in schools,” university professor of philosophy and political commentator Žarko Puhovski says.

Despite Croatia being a majority Catholic country, every fourth marriage ends in divorce and a decreasing number of couples are deciding to marry.

“The church’s influence on citizens is far greater regarding political than moral views. Church morality is accepted in principle, but political views supported by the church gain additional power. That is why the referendum is causing a short-term increase in the influence of the church, which has for years been weakening,” Puhovski explains.

Church leaders are often complaining about the non-existent dialogue with the current, left-wing government, especially regarding the issues they consider to be related to religion – education of children, family care and marriage.

“The ultimate success of this referendum is in showing the power of the church in Croatia. It has shown the government that it can move masses of people so in the future, the government will have to think carefully before making any decision which could harm their interests,” said a group of Roman Catholic theologists in a joint letter made public on 29 November.

“The relationship between the church and the state has mostly been disturbed by militant statements of individuals from the Catholic Church leadership, which seem to be best served with a one common mindset rather than political and worldview pluralism,” sociologist and ex-ambassador for the Holy See, Ivica Maštruko says.

“We are not dealing with a normal criticism of the current social state and relations, but bigotry, inappropriate discourse and civilisational and religious malice,” Maštruko added.

An example of such a discourse is provided by reputable former minister and theologist Adalbert Rebić who, earlier this year, was quoted as saying: “The conspiracy of faggots, communists and dykes will ruin Croatia.” Pastor Franjo Jurčević was convicted for publishing homophobic and extremist posts on his blog.

But in the campaign for the referendum the Catholic Church was joined by representatives of the other most influential religious communities in Croatia – Orthodox Christians, Muslims, Baptists and the Jewish community Bet Israel. Together they supported the referendum and invited the believers to vote in order to “secure a constitutional protection of marriage”. Religious communities in Croatia are usually rarely seen forming such shared views.

“The most interesting thing is the agreement between the Catholic Church and the Serbian Orthodox Church which have in the past twenty years completely missed the chance to initiate reconciliation, dialogue and co-existence during and after the wars in ex-Yugoslavia. Religious communities in the region can obviously agree only when they find a common enemy, which in the case of this referendum are LGBT persons,” Cirkvenec says.

Žarko Puhovski considers it indicative that religious communities in Croatia succeed in forming shared views only with regards to sexual morality.

“They have failed to reach a consensus on any other moral or political issue,” he concludes.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org