Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

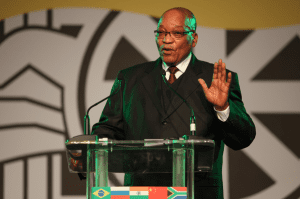

Jacob Zuma (Photo: Jordi Matas / Demotix)

With the new year comes a new battle in South Africa as critics hit back at the proposed “draconian” Cybercrimes and Cybersecurity Bill they say doesn’t differentiate “between espionage and an act of journalism”.

The bill comes against the backdrop of ongoing government hostility towards the media. Exposés by journalists of corruption and cronyism within the ranks of the governing African National Congress (ANC) have led to accusations by the party that the media casts it in a “negative light” and acts in opposition to it.

On the face of it, the legislation is a ham-fisted attempt to push through by stealth key aspects of the stalled and deeply flawed Protection of State Information Bill, which was first introduced in parliament in March 2010.

Dubbed the Secrecy Bill, it has reached the penultimate step in the legislative process, requiring only that President Jacob Zuma sign it into law. But, in the face of stiff opposition and threats of a Constitutional Court challenge, it has been gathering dust on the president’s desk for over two years, unsigned.

“Whole sections of the [Cybercrimes] Bill are copy-and-paste from the Secrecy Bill,” says Murray Hunter, a spokesman for the freedom of expression Right2Know (R2K) campaign. A draft version of the bill was published in August last year, with two months allowed for comments.

In a preliminary submission, R2K says some provisions of the Cybercrimes Bill go way beyond those contained in the Secrecy Bill and include “harsh, draconian penalties that would muzzle journalists, whistleblowers and data activists”.

The bill makes it an offence to “unlawfully and intentionally” hold, communicate, deliver, make available or receive data “which is in possession of the state and which is classified”. Penalties range from five to 15 years in jail and, worryingly, there is no public interest defence or whistleblower protection.

R2K has also highlighted some of its key objections to the bill in a document entitled What’s Wrong With the Cybercrimes Bill: The Seven Deadly Sins.

Hunter concedes that while policies that promote the online security of ordinary citizens are necessary, the bill is part of a raft of new “cybercrime laws popping up across the world that threaten internet freedom”.

“The policy debates in the US and UK are examples of a renewed appetite for backdoor access to privately-owned networks,” he says. “The idea is usually that governments say they want to users to have greater security against ‘outside’ threats, but still want government agencies to be able to penetrate that security.”

The bill effectively hands over the keys of the internet to South Africa’s Ministry of State Security and would dramatically increase the state’s power to snoop on users and wrests governance away from civilian bodies.

“Remember that security means protecting people’s information not only from ‘cybercriminals’, but also from state surveillance,” says Hunter.

Put another way, it’s a bit like having a really great lock on your front door, but leaving the spare key under the mat; either a system is secure against all threats or it is vulnerable to all threats.

Another big concern is that the bill, in its current form would potentially criminalise digital security analysts.

“One of the major protections for internet users’ security is a global community of security analysts and researchers who test the systems, apps and websites as a civic duty, in order to point out and fix security flaws that put the general public at risk,” says Hunter. “Basically, they are online activists who are constantly trying to find security weaknesses in other people’s systems [often belonging to governments and private companies] in order to point them out and get them fixed.”

But the bill would make these practices a criminal offence unless it was “authorised”, and in doing so would potentially make ordinary users less safe.

All of these moves contain uncomfortable historical echoes — it’s only been 22 years since South Africa became a democracy, and surveillance against citizens was among the apartheid government’s notorious specialties.

So the idea of a democratically-elected government, backed up by laws that legitimise intercepting its private citizens’ information, is especially fraught.

As temperatures soar and an “epic drought” tightens its grip on the country, all indications are that it’s going to be a long, hot summer in more ways than one, as activists and journalists prepare to fend off yet another attempt to curb South Africa’s hard-won freedom.