Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The biggest joke in Cassandra Vera’s case is a year-long prison sentence for 13 humorous tweets about the assassination of Francoist minister Luis Carrero Blanco. A liberal democracy has sent someone to jail for making jokes in poor taste.

Vera, who is now 21 years old, published tweets between 2013 and 2016 about the assassination of Blanco, dictator Francisco Franco’s prime minister. He was killed in a car bomb attack carried out by the Basque terrorist organisation ETA in Madrid on 20 December 1973.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Even though the Audiencia Nacional sentence can be appealed and probably won’t entail prison, it is obscene. In recent times there have been many worrying cases in Spain: the burning of the image of Juan Carlos de Borbón was punished with a €2,700 fine; the singer César Strawberry was sentenced to one year in prison because of six tweets which, according to the ruling, “humiliated victims of terrorism”; other users of this social network have been convicted or prosecuted. The balance does not always fall on the same side. On other occasions, the left that has asked that action to be taken against bishops who pronounce homophobic homilies or against Hazte Oír, an ultra-Catholic outfit which launched an anti-transgender campaign. A side effect is that these censorious tendencies turn rather unpleasant people and groups into martyrs of freedom of speech.

Many people seem interested in stopping the circulation of words and ideas they dislike. But, of course, it is precisely those ideas and words that someone dislikes that require the protection offered by freedom of speech. On the other hand, this protection is offered regardless of the merit of what is stated: defending the right to express an opinion does not mean that we agree with it or that this opinion is protected from criticism, rebuttal or derision. As Germán Teruel, a lecturer in the Universidad Europea de Madrid, has written: “Recognition of freedom of expression means that there are certain socially harmful, harmful or dangerous manifestations that are going to be constitutionally protected.” Freedom, Teruel maintained, demands responsibility, respect and indifference.

In Vera’s case, the article that has been applied (578 of the Penal Code, which punishes “glorification or justification” of terrorism) has, for some experts, debatable aspects. It also seems designed to combat something else: the activity of a terrorist organisation which had propaganda outfits and capacity for social mobilisation. In this case, and in a few others, legislation originally designed to solve different problems has been applied to Vera. Often, the law is not being used to combat terrorism, but to prosecute and convict people who say stupid things on Twitter. Cases such as this, as Tsevan Rabtan has written, have the added effect of delegitimising measures against the justification and glorification of terrorism in general.

This example is especially striking: the victim of terrorism was also the prime minister of a dictatorial government. The attack (where there were other casualties, and where two other people died) took place more than 40 years ago, long before Vera was born. The killers benefited from 1977’s amnesty law. The assassination of Carrero Blanco is an iconic moment in Spanish history. Like many such milestones it endures a certain depersonalisation and produces constant reinterpretations, some of them frivolous or insensitive. Trying to stop this happening causes injustice – only the tragedies of some victims are protected. On the contrary, if it was done efficiently, the result would be a society where we could not talk about many things.

As legal scholar Miguel Ángel Presno Linera explained, in cases such as Strawberry’s and Vera’s: “It is legally incomprehensible that the context in which they [their comments] were issued is not taken into account; in the first case, the Supreme Court reversed the acquittal agreed by the Audiencia Nacional – ‘It has not been proven with those messages César [Strawberry] sought to defend the postulates of a terrorist organization, nor to despise or humiliate their victims’ – and sentenced him on the basis that the purpose of his messages was not relevant – what had to be valued was what he had really said.”

Moreover, these interpretations don’t take full account of the way social networks work. Networks cannot be a lawless terrain and freedom of speech is always regulated, but the type of communication that is established based on them must be taken into account too: the importance of expressive use, the effects that can be or want to be achieved. When you read something without taking into account the context, not giving value to its intention and not discriminating between what is said seriously and what is said in jest, you simply misread it.

The tweets that originate these rulings are often rejectable, but this kind of legal answers have wider and more dangerous effects. They also serve to intimidate us: to impoverish our conversation and our democracy and to make us all less free.

Daniel Gascón is the editor of Letras Libres Spain.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Coming soon: The spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at how pressures on free speech are currently coming from many different angles, not just one. Spanish puppeteer Alfonso Lázaro de la Fuente arrested last year for a show that referenced Basque-separatist organisation ETA. In an Index exclusive, he explains what the charges have meant for his personal and professional life.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1491210162193-902bf89d-62e7-0″ taxonomies=”199″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

In this guest post, the editor de Letras Libres España explains the uproar over of children’s book.

In this guest post, the editor de Letras Libres España explains the uproar over of children’s book.

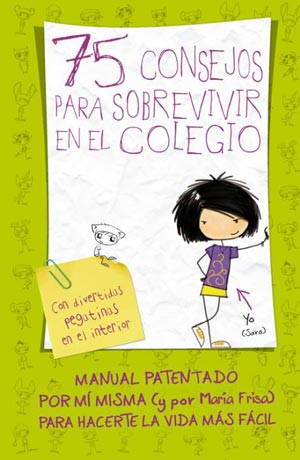

More than 30,000 people have signed a petition to have 75 Tips to Survive School (75 Consejos para Sobrevivir en el Colegio) — a book by author María Frisa and published by Alfaguara in 2012 — pulled from the market in Spain.

The petition, hosted on Change.org, accuses the book of giving “toxic advice”, and of inciting sexism, disobedience and bullying. The publishing house said it will not withdraw the book, although the cover will emphasise that it is a work of fiction. The author issued a statement in which she regretted the misunderstanding surrounding her book.

The charge is old and familiar: Frisa is accused of corrupting the young. And the strategy is also old and familiar: intolerance and the literal mind posing as protecting the weak. We tend to think that those who restrict freedom of speech have evil motives. But they almost always act in defence of a noble cause, convinced of their good intentions.

The initial complaint came from @YaraCobaain, a Twitter user, on 23 July, and the petition was launched by Haplo Schaffer, a YouTuber. It was amplified by the media, which often merely repeated the petition’s ideas and points of view, thus distorting the contents of the book and presenting excerpts without explaining the context. It seems reasonable to assume that the vast majority of the signatories have not read the book. When Schaffer wrote the petition, he hadn’t either.

A careful reading of the petition on Change.org could have triggered some alarm: for example, the fact that it describes 75 Tips to Survive School as addressed to girls, as if in Spain books were segregated by gender (the book is not even directed towards a female reader: tip number 22, for example, is “finge ser simpático”, and the adjective “simpático” is in the masculine form). The campaign and some of the press presented the book as if it were a manual. Actually, and very clearly, Frisa’s book, which is part of a series, is a literary work of humorous fiction. The narrator, Sara, is a fictional character. She has irreverent opinions, describes tactics that are not presented as morally exemplary, and concocts plans which often go awry. The book’s tone is naive and childish. A reader might find the joke more or less funny, but it’s clearly a joke.

Regardless of the work’s genre, and though it might seem odd if someone does not like a book or its ideas they can choose not to buy it, and even not to read it. On top of ignoring the characteristics of the object that offends them, the petition’s signatories seem to overestimate the influence of literature on our behaviour and to underestimate the reading comprehension of the young – we can safely expect that it won’t always be as rough or twisted as the campaigners’. If we applied the same standard to every book written for children, or to every work that may fall into a child’s hands, we may have to do without a few, from Tom Sawyer to Matilda. We would probably have to withdraw The Simpsons and Robert Louis Stevenson as they would be considered a peril for the young, and I don’t know what we’d make of the Bible. Literature would lose complexity, richness, humor and the ability to help us understand different viewpoints and behaviours.

Although the campaign has denounced what it says is an incitement to bullying, it has harassed the writer and has intimidated the publishing house. In the book’s page on Amazon, the vast majority of comments were made after 23 July 2016, and they contain the ideas of the petition. Murcia, a region in Spain, has called for the withdrawal of the book. The author has claimed that she has received death threats. When Frisa published her statement, Schaffer, who has later distanced himself from the threats and insults of some campaigners on Twitter and on a commented reading of the novel on YouTube, wrote: “You are disgraceful and a coward, @MFrisa. I have been extremely polite so far, but enough is enough.” He tweeted to the publishing house: “If you want to present a coherent explanation, @Alfaguara_es, you still have time. If not, face the consequences, they won’t be nice.” Interestingly, in the explanations of some of his YouTube videos Schaffer defends the importance of freedom of speech.

In The Art of the Novel, Milan Kundera writes: “The word agélaste: it comes from the Greek and it means a man who does not laugh, who has no sense of humour. Rabelais detested agélastes. He feared them. He complained that the agélastes treated him so atrociously that he nearly stopped writing forever”

In 2016, 30,000 people in Spain have demanded the banning of a children’s book that in most cases they haven’t read. The petition states: “It is intolerable that such content is published, publicised and disseminated.”

Frisa has had the support of her publishing house, as well as some colleagues and members of the literary world. But one of the most striking things about this case is her helplessness before hysterical vigilantes and the stampede of people who have more energy to be indignant than time or desire to be properly informed. It’s partly explained by the dynamics of social networks, which are difficult to stop. But the role of many journalists has also been regrettable. Firstly, their job is to report events as they are, and in this case many have failed to do so. Secondly, those whose living depends on freedom of speech should be wary of this kind of phenomenon: armed with the best intentions, one day they might also come to shut you up.

A version of this article originally appeared in Letras Libres.