Life After Leveson: The UK media in 2014

Britain has always had a complicated relationship with the free press. On the one hand, Milton’s Apologia, Mill’s On Liberty, Orwell’s volleys at censorship and propaganda.

On the other hand, there is a sense that journalists, editors and proprietors are at best incompetent and at worst genuinely venal people whose sole interest is making others miserable.

This ambivalence carries over into the political debate about the media, and the laws and regulations governing the press and broader free speech issues. All British politicians pay lip service to free speech, but the records of successive governments have been far from perfect. For every success, there is a setback.

This paper will provide a brief overview of the state of media freedom in the UK today

Press regulation and the Royal Charter

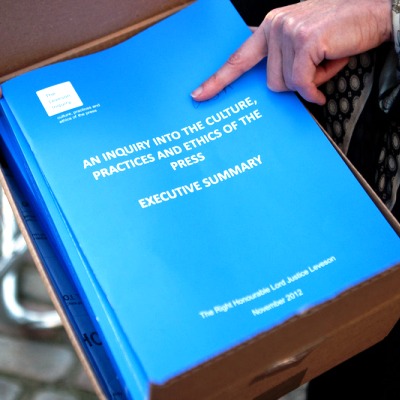

The Leveson Inquiry into the press reported in November 2012, with numerous recommendations on how press regulation should proceed. After months of negotiation led to deadlock over the issue of a “statutory backstop” to a regulator, in April 2013 the government attempted to resolve the issue, publishing a draft of a “Royal Charter” for the regulation of the press. In spite of the newspapers’ attempt to put forward their own competing royal charter, the Privy Council officially approved the government version in October 2013.

While the government and supporters claim that this is insulated from political interference, requiring consent of all three main parties in both houses (as well as a 2/3 majority) before the charter can be altered, critics say that royal charters, granted by the Privy Council, are essentially still political tools.

But how did we get to this point?

The Leveson Inquiry was called in response to the phone hacking scandal which gripped the country in 2010 and 2011. Journalists and contractors for News of the World, News International’s hugely successful Sunday tabloid, were alleged to have hacked the voice message of 100s of people, most notoriously murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler. Several criminal trials of senior News International figures continue at time of publication.

As allegations of dubious behaviour began to be made against other papers, judge Sir Brian Leveson was charged with leading an inquiry into the industry. The inquiry, which opened in late 2011, heard from a huge range of people, from celebrities to civil society activists.

An increasingly polarized debate has seen the newspapers lined up on one side, opposed to the current Royal Charter, and campaign group Hacked Off, as well as the major political parties, on the other. The newspapers plan to set up their own regulator, the Independent Press Standards Organisation, which may not seek recognition under the Royal Charter. It is claimed that IPSO will be operational by 1 May. This would be funded by the newspapers, with representation from the industry on its governing bodies.

Hacked Off and their supporters, who claim to represent the interests of victims of phone hacking and press intrusion, say that the newspapers cannot “mark their own homework”, and insist that any regulator must be “Leveson compliant” and recognised under the Royal Charter.

There have been confusing political signals. While Culture Secretary Maria Miller suggested that IPSO, if it functioned well, may not need to apply for recognition, the Prime Minister David Cameron told the Spectator magazine that he believed that the Royal Charter was the best deal the press would get, and that publishers should sign up lest a more authoritarian scheme be introduced.

Index on Censorship has opposed the Royal Charter and supporting legislation on several grounds.

– Changing the Royal Charter While supporters claim the Royal Charter cannot, practically, be changed by politicians, Index believes it would be possible to gain the two-thirds majority required in both houses to alter it, particularly if there were to be another hacking-style scandal. The Privy Council is essentially a political body, and recognition by royal charter a political tool.

– Exemplary damages The Crime and Courts Act sets out that an organisation which does not join the regulator but falls under its remit will potentially become subject to exemplary damages should they end up in court. In addition, even if they win, they could also be forced to pay the costs of their opponents. While it is claimed that membership of a regulator with statutory underpinning is voluntary, it is clear that there are severe, punitive consequences for those who remain outside the regulator. There is controversy over whether this is compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

The imposition of exemplary damages is likely to have a strongly chilling effect on freedom of expression – this could be particularly felt by already financially squeezed local publications and small magazines.

– Corrections The Royal Charter proposes the regulator will be able to “direct” the wording and placement of apologies and corrections. This is an effective transfer of editorial control. It represents a level of external interference with editorial procedures that would undermine editorial independence and undermine press freedom. A tougher new independent regulator could reasonably require corrections to be made, but directing content of newspapers is a dangerous idea.

– Scope The Royal Charter is designed, in its own words, to regulate “relevant” publishers of “news-related material”. It sets out a very broad definition of news publishers and of what news is (including in the definition celebrity gossip). Despite some subsequent attempts by politicians to establish some exclusions, such as for trade publications and charities for instance, the attempt to distinguish press from other organisations remains problematic. In a media industry undergoing rapid change, distinctions between platforms are increasingly blurred, and stories from unlikely sources can have every bit as much impact as those from the traditional media whose power pro-regulation activists seek to curb.

The next few months will be crucial as IPSO and alternatives, such as the IMPRESS project, take up positions. IPSO will be keen to recruit publications that have not already joined and present itself as fait accompli, pointing out that nowhere in the Leveson recommendations is there specific mention of a Royal Charter.

But at the core of the entire argument is the fundamental fact that the government has been willing to use coercive, punitive measures specifically directed at the press.

Libel – a free speech victory?

On 1 January, the Defamation Act 2014 became statute. The new law, represented a victory for the Libel Reform Campaign led by Index on Censorship, English PEN and Sense About Science. The LRC had its roots in two things – English Pen and Index on Censorship’s report “Free Speech Is Not For Sale” and Sense About Science’s campaign “Keep Libel Laws Out Of Science”.

That campaign identified key problems with England’s libel law, which was simply not fit for the internet age. Among the issues were the ease with which foreign claimants could bring cases in London courts, and the lack of a coherent statute of limitation on web publication.

The new act, while still far from perfect, is, at least on paper, an improvement on what has gone before. It should in theory provide greater protection for writers.

Among the changes are the introduction of a strong public interest defence, a one-year statute of limitation on online articles (where previously each new “download” counted as a new publication), and a “serious harm” test for corporations wishing to sue for defamation.

One major point of concern is the refusal of Northern Ireland’s government to update its statute books in line with that of England and Wales. Libel lawyer Paul Tweed, who practices in Belfast, Dublin and London, has pointed out that wealthy litigants hoping for a more claimant-friendly regime may now take cases to Belfast rather than London. It is imperative that pressure continues to be put on the political parties in Northern Ireland to introduce the new legislation.

Surveillance and protection of sources

There is little doubt about what was the biggest global story in 2013. The revelations about global surveillance carried out by the US’s National Security Agency, with the help of Britain’s GCHQ, dominated much of the global conversation. But while the US has made some noises about reviewing its surveillance procedures (though it has shown no intention of halting its pursuit of whistleblower Edward Snowden), the UK government managed a very special combination of burying its head in the sand and shooting the messenger.

The Prime Minister warned the Guardian that it should stop publishing revelations or face legal action. Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger was summoned before parliament and accused of deliberately endangering British security.

Security officials even visited the Guardian and demanded that hard drives containing leaked material be destroyed in front of them, in spite of the fact they were aware the data was also held elsewhere.

David Miranda, the partner of the Rio-based journalist Glenn Greenwald, was stopped at Heathrow airport under terror legislation. This was clearly done in order to confiscate source material.

That action was challenged in the courts by Miranda, with Index on Censorship entering evidence in support of the case. The legal challenge to the detention of Mr Miranda has been dismissed by the High Court, though there is the possibility of an appeal.

The case raises serious questions about protection of journalists’ materials and sources. There was also grave concern that terror legislation was used against a person carrying out journalistic activity.

Meanwhile, the government has proposed, as part of the deregulation bill, a new system which would make it easier for authorities to force journalists to hand over materials and information about sources. The Deregulation Bill could, if passed unamended, strip away safeguards for journalists faced with demands for their materials from police, removing the requirement for judicial scrutiny of such demands.

Conclusion

2014 will be a crucial year, not just for newspapers, but for free speech for everyone in the UK. For as the wall between publisher and consumer is rapidly being dismantled, it will become harder and harder to compartmentalise press freedom and general principles of free speech.

While the reform of our libel laws will, we hope, be of great benefit to to free expression in the UK and beyond, there are still several areas where this government can act to safeguard the free press and free speech more broadly in the coming year. Chief among these is that we must allow press self-regulation to proceed without coercion. No one should be forced to sign up to the press Royal Charter, and no one should be subjected to exemplary damages. In short, self-regulation should be just that.

Moreover, the government should state its commitment to protection of journalistic sources, a crucial cornerstone of the fourth estate which has come under severe threat as a result of the Miranda case.

Finally, the government should ensure that Belfast does not become a haven for libel tourism, by doing everything it can to support the extension of the new Defamation Act to Northern Ireland.