29 Mar 2019 | Campaigns -- Featured, Magazine, Press Releases, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”97% of editors of local news worry that the powerful are no longer being held to account ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Ninety seven per cent of senior journalists and editors working for the UK’s regional newspapers and news sites say they worry that that local newspapers do not have the resources to hold power to account in the way that they did in the past, according to a survey carried out by the Society of Editors and Index on Censorship. And 70% of those respondents surveyed for a special report published in Index on Censorship magazine are worried a lot about this.

The survey, carried out in February 2019 for the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, asked for responses from senior journalists and current and former editors working in regional journalism. It was part of work carried out for this magazine to discover the biggest challenges ahead for local journalists and the concerns about declining local journalism has on holding the powerful to account.

The survey found that 50% of editors and journalists are most worried that no one will be doing the difficult stories in future, and 43% that the public’s right to know will disappear. A small number worry most that there will be too much emphasis on light, funny stories.

There are some specific issues that editors worry about, such as covering court cases and council meetings with limited resources.

Twenty editors surveyed say that they feel only half as much local news is getting covered in their area compared with a decade ago, with 15 respondents saying that about 10% less news is getting covered. And 74% say their news outlet covers court cases once a week, and 18% say they hardly ever cover courts.

The special report also includes a YouGov poll commissioned for Index on public attitudes to local journalism. Forty per cent of British adults over the age of 65 think that the public know less about what is happening in areas where local newspapers have closed, according to the poll.

Meanwhile, 26% of over-65s say that local politicians have too much power where local newspapers have closed, compared with only 16% of 18 to 24-year-olds. This is according to YouGov data drawn from a representative sample of 1,840 British adults polled on 21-22 February 2019.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]The Index magazine special report charts the reduction in local news reporting around the world, looking at China, Argentina, Spain, the USA, the UK among other countries.

Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley said: “Big ideas are needed. Democracy loses if local news disappears. Sadly, those long-held checks and balances are fracturing, and there are few replacements on the horizon. Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be.”

She added: “If no local reporters are left living and working in these communities, are they really going to care about those places? News will go unreported; stories will not be told; people will not know what has happened in their towns and communities.”

Others interviewed for the magazine on local news included:

Michael Sassi, editor of the Nottingham Post and the Nottingham Live website, who said: “There’s no doubt that local decision-makers aren’t subject to the level of scrutiny they once were.”

Lord Judge, former lord chief justice for England and Wales, said: “As the number of newspapers declines and fewer journalists attend court, particularly in courts outside London and the major cities, and except in high profile cases, the necessary public scrutiny of the judicial process will be steadily eroded,eventually to virtual extinction.”

US historian and author Tim Snyder said: “The policy thing is that government – whether it is the EU or the United States or individual states – has to create the conditions where local media can flourish.”

“A less informed society where news is replaced by public relations, reactive commentary and agenda management by corporations and governments will become dangerously volatile and open to manipulation by special interests. Allan Prosser, editor of the Irish Examiner.

“The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial. Belgian journalist Jean Paul Marthoz.

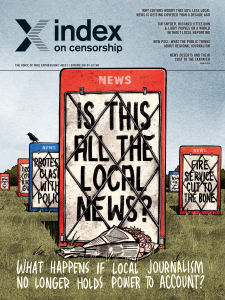

The special report “Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?” is part of the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Note to editors: Index on Censorship is a quarterly magazine, which was first published in 1972. It has correspondents all over the world and covers freedom of expression issues and censored writing

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on Is this all the Local News?

Index on Censorship’s spring 2019 issue asks Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account? We explore the repercussions in the issue.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on iTunes and Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the Local News?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores what happens to democracy without local journalism, and how it can survive in the future.

With: Richard Littlejohn, Libby Purves and Tim Snyder[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Nov 2018 | About Index, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine gave the following speech at Eurozine’s 29th European Meeting of Cultural Journals. This year, the meeting was entitled ‘Mind the gap: Illiberal democracy and the crisis of representation’. Panels discussed the rise of the populist right as result of a failure of institutional politics and the role of the liberal media in the dynamics of polarisation.

As you know, we British are very fond of tea. Today, I am going to look at three Ts:

- Transparency

- Trust

- And why terms and conditions apply.

The over-arching questions here are what is the democracy we want and what is the technology we want to achieve that?

In other words, how can we make it happen?

Long, long ago sometime in the 1990s I went to the BT Lab in Ipswich where they were developing the house of the future, where the washing machine talked to you and you could talk to everything. Then the lab guys said, it will be great, we’ll know what you are wanting to buy and when it’s on sale or you are out of it someone will phone you and tell you.

Ugh, that sounds creepy, I said. No, they said, it will be great.

And so it came to pass, only it wasn’t the phone that called but social media and the internet that knew what I wanted and the phone call was a pop-up ad. And I still think it is creepy.

Because the only person I want to know whether I am out of milk, or I want to buy a new bed, is ME.

One friend even told me that Google knew he had Multiple Sclerosis before he did. As ads for the MS Society keep popping up when he was online, and after a while he began to wonder why.

Right now Google is hoovering up our data, who we email, what we search for, what we want to buy. Not just Google, but Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and entertainment companies like Netflix and the BBC line up a list of programmes they know we want to watch even though we haven’t even heard of them yet.

They are offering to take decisions away from us, by letting them do it. It’s tough out there, so may we choose you a book, a film, a life, a friend who agrees with you, and pretty soon you won’t realise other choices have been taken away.

But actually in many ways this is nothing new. In 2006-10 I worked for a think tank that was pretty close to the government of the time, and it was well known that when Number 10 wanted to know what people were thinking, buying, feeling, —– a societal snapshot if you will —– they talked to the supermarkets, because back then the supermarkets were seen as the leaders in data collection. They knew if more people were buying rom coms, spending less on the weekly shop or stocking up on tins because they thought there might be a crisis.

Back then, and now, supermarkets were gathering data from loyalty cards, then Google, Facebook and others realised we would give loads of information about ourselves to them for free, if they created something we wanted. So they did.

It was our choice. We chose free email, when paid was an option. Other alternatives were, and are available. We choose a search engine that tracks our data. We chose to add our date of birth, photos, and holiday details to Facebook. Handing it over without question.

Do you remember reading one of those terms and conditions apply documents for the first time, and realising you were giving an app the opportunity to read your emails and look at your photos? I do. But people happily signed up and got stuff for free. And the deal was on.

And why is this a democratic issue? The thing is in a democracy we had and have a responsibility to make decisions, as well as to be informed and to be represented.

And in democracies we need to decide more, rather than have decisions thrust upon us. In giving away our data we didn’t realise that all that information would be collated into huge data banks, where people could work out things, like this person with a car is far more likely to vote for Trump than this person who uses public transport. And from there, all those people with cars would be targeted with messages before the US election. And all this data analysis about what people did with their lives would be used to target people with messages in the run up to the Brexit referendum.

Transparency in a democracy means what the impact of our decisions are. I also want to know what the government is doing on my behalf. And I want transparency from companies operating in my country that may have impact on my democracy. I want to trust that the political system is working, and that is not being driven by shadowy figures and ideas that are hidden from view.

So transparency of who we ALLOW to access our data, and having a personal contract with companies saying what they can and can’t do MUST be part of our future democracies.

We also need more transparency about what political parties in an election period are saying to voters. In previous decades we knew what arguments were being made to different parts of the electorate because we saw the billboards or the TV ads or the newspapers advertising, or the interviews.

But what we are seeing increasingly used in the run up to elections is hidden messages, hidden politicking.

The electoral bodies need to catch up with those digital leaps and make some changes to what is allowed in election periods. I am going to argue that each campaign — needs to lodge one example of each message/campaign with them, whether they are on Facebook or on the side of the road, so those that don’t receive them know about them, and are able to discuss and debate whether there is any truth or value in them. In the UK the Electoral Commission needs to make changes so parties can not use hidden tactics. There will be hurdles and opposition, but a system needs to work, in the same way, we used to be able to see an ad, we should then be able to access at least on the Electoral Commission, for instance, each major campaign that a party is running, giving others the chance to fact check or oppose it.

Because a democracy should be a noisy, open society where there is disagreement and argument and there is space to do so.

Transparency breeds more trust, and that’s something that politicians and political systems need in order to operate. If no one believes in the system then it fails.

Democracy must supply its own terms and conditions, ones that create structure for rights and responsibilities, both for its citizens and for corporations operating within it.

These include paying tax, living within the laws of the land, and supporting its essential freedoms.

We do not want to hand over the right to choose what we are allowed to see or read or hear to unelected Silicon Valley corporations. We should not be happy with governments that try to do just that, and suggest that massive California-based companies should be selecting news or views for us. We should make those choices ourselves.

At Index, we have already heard of videos being taken down showing Rohinga Muslims being persecuted, after pressure from the Burmese government — what this does is attempts to undermine evidence gathering by human rights organisations. We hear of numerous issues where the Chinese government attempts to stop its citizens from having access to books and articles and news items on the internet, often by pressurising digital media from publishing them. These are governments pressurising social media and digital companies to censor or restrict access, but in other nations governments seem to want to hand over those decisions to social media, rather than reviewing the law and going through a democratic process.

And back to those terms and conditions that come with apps and other tools, sometimes these run to as many as 30,000 words — the size of a small book — that is not a document designed for people to read or understand. Simple, straightforward contracts need to replace this culture of hidden meanings, designed to mystify and mislead.

We should know what we are signing up for, with our new era of democracy and the technology that goes with it.

We need tech that works to help us be informed, be curious, to connect, and of course we should remember that these tools do exist for good, but they can also be misused to surveil and suppress.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1541429193469-bf25f4e9-3ba3-6″ taxonomies=”5641″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Mar 2018 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/7kseuuaARZQ”][vc_column_text]The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) is one of the only human rights organisations still operating in a country increasingly hostile to dissent and in which countless civil society organisations have been forced to close. The commission coordinates campaigns for those who have been tortured or disappeared, as well as highlighting numerous incidences of human rights abuses.

“Our main goal to achieve in the future, which is stated in our mission, is to empower individuals to acquire their rights, promote a culture of democracy in the Egyptian society, and expand human rights to every home in Egypt,” ECRF told Index. “But in the end of the day we decide to carry out with our work regardless of the challenges because if everyone is silenced this would be the ultimate gain to the current regime, and the ultimate victory to Egypt’s state of fear.”

Between August 2016 and August 2017, the ECRF documented 378 cases of enforced disappearance many of whom were students. The cases of the disappeared are not reported in the heavily censored local media, and the commission’s website and social media sites are some of the few places their plight can be publicised, reported and mapped.

The highly restrictive and repressive environment Egypt has made it increasingly difficult for the organisation to do its work.

Their website was blocked in September in government measures designed to close the organisation down, but the ECRF managed to create a parallel website to maintain their presence and engagement with the public. Twice last year ECRF’s headquarters was raided by security forces with two staff members being arrested. As a result, the staff need help dealing with the risks of being arrested, as well as dealing with the interrogation process and knowing how to protect information.

Over the past 12 months the ECRF has been fighting censorship and defending human rights in two ways. The first is through the criminal justice programme which tackles issues of torture and enforced disappearances in Egypt. It has been particularly focused on the arrest of activists who took part in demonstrations against Egypt’s agreement to cede two uninhabited islands in the Red Sea to Saudi Arabia.

Secondly, ECRF has worked on challenging censorship imposed on student associations in universities. Recently the commission launched an online platform to bring students and practitioners online to discuss a student charter related to freedom of association in universities. The platform was heavily criticised by the ministry of higher education in Cairo, which led to further condemnation of it in official media outlets.

As a direct result of the work ECRF has carried out over the past year, there has been an increased awareness of enforced disappearances, media censorship, the scale of torture, and violations of freedom of association and expression in media and universities.

“ECRF is honored to be shortlisted alongside three peer organizations/campaigns also facing severe human rights challenges in their own countries,” said ECRF. “The international recognition of ECRF’s efforts in campaigning for fundamental freedoms emboldens its members and staff in their resilience to strive for human rights and democracy in Egypt. Regardless of the winner, progress towards equal rights in Russia means progress in Egypt and progress in Kenya means progress in Iran and vice-versa.”

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460×490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522065946315-a2955265-bb40-3″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Mar 2016 | News and features

Peter Kellner is president of YouGov and a contributor to Index on Censorship magazine. Kellner discusses the results of a YouGov survey about rights across seven European democracies and the United States. Full results are available here.

As far as I know, North Korea is the only significant country whose citizens have never been polled. Everywhere else, it is possible to discover what people think on at least some issues; and in the world’s democracies we can ask about the most sensitive social and political topics and obtain candid answers. In less than a century, and in many countries less than half a century, opinion polls have given people a voice of a kind they never had before.

It is against this backdrop that I chose the topic for my final blog for YouGov, before stepping down as president. The rise of polling in different countries has accompanied the spreading of democracy and human rights. We can do something that our grandparents never could: find out which human rights matter most to people – and to do it, simultaneously, in a number of countries. In this case we have surveyed attitudes in seven European democracies and the United States.

This is what we did. We identified thirty rights that appear in United Nations and European Council declarations, in the British and American Bills of Rights and, in some cases, are the subject of more recent debate in one or more countries. To prevent the list being even longer, we have been selective. For example, we have omitted “the right of subjects to petition the king”, and the right of people not to be punished prior to conviction, which were promised by Britain’s Bill of Rights. Matters requiring urgent attention in one era are taken for granted in another.

Even so, thirty is a large number. So we divided the list into two, and asked people to look at each list in turn, selecting up to five of the 15 rights from each list that “you think are the most important”. This means that respondents could select, in all, up to ten rights from the thirty. This does not mean that people necessarily oppose the remaining rights, simply that they consider them less important than the ones they do select.

This is what we found:

- The right to vote comes top in five of the eight countries (Britain, France, Sweden, Finland and Norway), and second in two (Denmark and the United States – in both cases behind free speech). Only in Germany does it come lower, behind free speech, privacy, free school education, low-cost health care and the right to a fair trial.

- In all eight countries more than 50% select free speech as one of the most important rights. It is the only right to which this applies.

- Views vary about the importance of habeas corpus – the right to remain free unless charged with a criminal offence and brought swiftly towards the courts. It is valued most in Denmark (by 49%) and the United States (40%). In Britain, where habeas corpus originated in the seventeenth century, the figure is just 27%.

- Rights to free school education and low-cost health care are selected by majorities in six of the eight countries. The exceptions are France and the United States. In the US, this reflects a different history and culture of public service provision. In France, unlike the other six European countries we surveyed, financial rights (to a minimum wage and a basic pension) come higher than the rights to health and education.

- France is out of line in three other respects. It has by some margin the lowest figure for the right to live free from discrimination – and the highest figures for the right to a job and the “right to take part with others in anti-government demonstrations”

- Few will be surprised that far more Americans than Europeans value the right to own a gun (selected by 46% of Americans, but by no more than 6% in any European country) and “the right of an unborn child to life” (30%, compared with 13% in Germany and no more than 8% in any of the other six countries).

- The French and Americans are also keener than anyone else on “the right to keep as much of one’s own income as possible with the lowest possible taxes”. In the case of the United States, this is consistent with limited expectations of public-sector provision of health, education and pensions. With France it’s more complex: public services do not rank as high as in the six other European countries, but jobs, pay and pensions matter a lot. In their quest for security, income AND low taxes, many French voters appear to make demands on the state that seem likely to lead to disappointment. Perhaps this, as well as the lingering memory of France’s revolutionary past, explains the enthusiasm of so many French voters on both Left and Right to mount anti-government demonstrations.

- In Europe, property rights matter less than social rights. In Germany only 6% regard ‘the right to own property, either alone or in association with others’ as one of their most valued human rights. The figures are slightly higher for France (14%) and Britain (16%) and higher still in the four Scandinavian countries (20-29%). Only in the United States (37%) is it on a par with the rights to free school and low-cost health care.

- There are striking differences in views to rights that are matters of more recent controversy. In most of the eight countries, significant numbers of people value “the right to communicate freely with others” (e.g. by letter, phone or email) without government agencies being able to access what is being said). Four in ten Germans and Scandinavians regard this as one of their most important rights, as do 35% of Americans. But it is valued by rather fewer French (29%) and British (21%) adults.

- Much lower numbers choose the right of gay couples to a same-sex marriage: the numbers range from 10% (Finland) to 19% (US). This is a clear example of a reform that, separate YouGov research has found, is now popular, or at least widely accepted – but not considered by most people to be as vital a human right as the others in our list.

- In six of the eight countries, many more people value “the right of women to have an abortion” than “the right of an unborn child to life”. The exceptions are France, where both rights score just 13%, and the United States, where as many as 30% choose the right of an unborn child to life as a key human right, compared with 21% who value a woman’s right to an abortion. The countries with the strongest support for abortion rights are Denmark and Sweden.

Those are the main facts. Each of them deserves a blog, even a book, to themselves. It’s not just the similarities and differences between countries that are significant, but the variations between different demographic groups within each country. (For example, British men value free speech more than women, while women place a higher priority on the rights to free schooling and low-cost health care. Discuss…)

Nor does this analysis tell us about direct trade-offs. How far are people willing to defend free speech in the face of social media trolls – and habeas corpus when the police and security services seek greater powers to fight terrorism? (Past YouGov surveys have generally found that, when push comes to shove, most people give security a higher priority than human rights.)

The results reported here, then, do not provide a complete map of how human rights are regarded in the eight countries we surveyed. But they do give us a baseline. They tell us what matters most when people are invited to consider a wide range of rights that have been promoted over recent decades and, in some cases, centuries. It is, I believe, the first survey of its kind that has been conducted.

It won’t be the last. Understanding public attitudes to human rights, like promoting and defending those rights, is a never-ending task. It is also a vital one, just like giving voters, customers, workers, patients, passengers, parents – indeed all of us in our different guises – a voice in the institutions that affect our lives. Which has been the purpose of YouGov for the past fifteen years and will continue to be so.

See the full results of the survey.

This article was originally posted at yougov.co.uk and is posted here with permission.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]