26 Jul 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021

Index’s new issue of the magazine looks at the importance of whistleblowers in upholding our democracies.

Featured are stories such as the case of Reality Winner, written by her sister Brittany. Despite being released from prison, the former intelligence analyst is still unable to speak out after she revealed documents that showed attempted Russian interference in US elections.

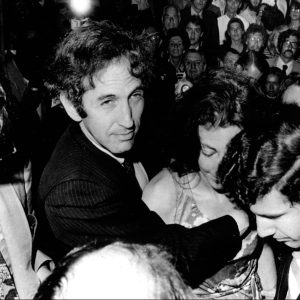

Playwright Tom Stoppard speaks to Sarah Sands about his life and new play title ‘Leopoldstatd’ and, 50 years on from the Pentagon Papers, the “original whistleblower” Daniel Ellsberg speaks to Index .

by Index on Censorship | 26 Jul 21 | Africa, Bosnia, Burma, China, Europe and Central Asia, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Slapps, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras | 0 Comments

Index's new issue of the magazine looks at the importance of whistleblowers in upholding our democracies. Featured are stories such as the case of Reality Winner, written by her sister Brittany. Despite being released from prison, the former intelligence analyst is...

26 Feb 2019 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Staff at Habari RDC with the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Digitial Activism

Despite the Regulator of Media for Congo forbidding the press from publishing provisional results of the 30 December 2018 general election in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, exit polls began circulating following the vote, with supporters of various political leaders trying to demonstrate that their man had won.

In response, authorities in the Congo shut down the internet and disrupted SMS services under the guise of tackling fake news. Social media companies were blocked, and Habari RDC’s internet service provider, DHI Telecom, in a meeting with our co-ordinator Guy Muyembe, made clear that they had cut our connection because they deemed our content to be dangerous.

The shutdown lasted for 20 days -- from 31 December 2018 until 19 January 2019 -- and had major implications for the country, except for select businesses which were allowed to retain full access. According to the Netblocks Cost of Shutdown Tool, the blocking of social media alone could have cost the country as much as $2,980,324. The shutdown also had implications for media outlets, including Habari and politico.cd, which was forced to temporarily move part of its staff to Brazzaville, the capital of the neighbouring Republic of the Congo, at significant cost.

To circumvent many of the difficulties we would face, and to ensure the continuation of publications on the site, some Habari staff in the east made their way to Rwanda so that they could access the internet without restriction. Crossing the border to Rwanda is free of charge, but staff who do not have Rwandan residency had to cross back before it closed at 10pm.

One of our editors, who was in France at the time on an internship, took over from the community manager living in Lubumbashi in the south of the country, who was responsible for our Twitter output.

Of the four Congolese cities where Habari has offices, only the one in Goma in the east of the country was partly operational. In Kinshasa, I was unable to moderate comments on Facebook or post articles. Having to confirm my identity on the social network through SMS was impossible with the service being down. Our Facebook feed, which is followed by more than 250,000 people, was mostly taken over by our webmaster living in Burundi.

Meanwhile in Kinshasa, mobile users were using sim cards from neighbouring Brazzaville. Kinshasa and Brazzaville are the two closest capital cities in the world, just four kilometres apart. Areas of Brazzaville are covered by the Democratic Republic of the Congo's neighbouring networks without the need for a roaming service, which saw many people go to hotels and inns near the Congo River during the shutdown.

In town, cybercafes using an undeclared satellite connection (Vsat) were offering service discreetly from $0.90 an hour for a phone to $1.20 per hour for a laptop. Intelligence agents were on patrol, harassing and arresting those using social networks. In some places, people were arrested just for having access to Facebook or Twitter.

At Ngobila Beach, the main port linking Kinshasa and Brazzaville, those selling sim cards and airtime were on alert, fearing arrest. Intelligence agents posing as customers were asking questions about whether or not you had access to social networks. I experienced this myself when I was asked by a guy to set internet parameters on his cellphone. The first giveaway was that his phone wasn’t a smartphone, so unable to access the internet on 3G or 4G. Secondly, he had a very poorly hidden walkie-talkie. Agents very often had visible guns, handcuffs and walkie-talkies. Those who obliged to help them with their made up internet problems were arrested and had their phones confiscated and searched. Many would have to pay money to be released.

At Ngobila, it cost around $15 to buy a sim card (normally $2-3) and about $25 for 600 megabytes to two gigabytes of data.

Four days before the announcement of the final election results, our provider agreed to grant us connection, but without access to social networks. The Kinshasa team of Habari had to use proxies and a VPN to work. With reduced bandwidth, it only made the job more difficult. At Habari, we can’t just rely on our website because social media is a cornerstone of our connection with followers. Blocking access to Facebook and Twitter reduced our audience saw a reduction in traffic to our website and videos.

During the shutdown, our only followers able to comment were either those outside the country or those locally using the neighbouring networks such as Airtel and MTN from the Republic of the Congo. Without access, our local editors were also unable to communicate with bloggers.

The Habari offices that suffered the most during the shutdown were those in Mbuji-Mayi in the centre and Lubumbashi in the south-east of the country, where staff were mostly unreachable. Our community manager in Lubumbashi sent us a brief message saying that he was connecting from a cybercafe with poor connection. Our co-ordinator and editor in Lubumbashi had limited access in the facilities of the University of Lubumbashi, where he is an assistant.

Mbuji-Mayi, where Habari’s local co-ordinator and editor-in-chief in charge of validating all articles is based, was totally silent.

Full connection was restored on 19 January, with SMS restored some days later.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type="post" max_items="4" element_width="6" grid_id="vc_gid:1550831937439-9f02fd99-561b-6" taxonomies="28191, 24389"][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Dec 2018 | Africa, Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features, Sub-Saharan Africa

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Guy Muyembe of the Digital Activism Award-winning Habari RDC at the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

The Democratic Republic of Congo will go to the polls on 23 December to elect a successor to incumbent president Joseph Kabila, who has been in power since January 2001 when he inherited the position from his assassinated father. The election was originally scheduled for 27 November 2016, a delay that has caused many problems for the country.

“The only thing that is certain about the election is the uncertainty that comes with it,” Guy Muyembe, president of Habari RDC, the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award Fellow for Digital Activism, tells Index. “Will it take place, will it not take place? How transparent will it be? In all likelihood, not very. And will the result tear the country apart?”

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists who give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. In recent months, they have been working towards covering what could be the first democratic transfer of power in the country’s history.

“But in the end, it will most likely be the same people in power,” Muyembe says. “As for Kabila himself, if he remains in the country, he might be operating from the shadows. This is definitely not a reassuring prospect.”

This is a tense time for the DRC. The UN high commissioner for human rights Michelle Bachelet has expressed concern at violence against opposition rallies around the country in the run-up to the election. Bachelet called on the authorities to ensure “the rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly – essential conditions for credible elections – are fully protected”. Muyembe is also concerned about what all this means for those running in opposition to the ruling People's Party for Reconstruction and Democracy: “They’re taking part in the campaign, but will they actually take part in the election in the end?”

During this period the risk factor for activists has been very high, Muyembe says. “They’re not protected legally, and it’s very easy to label them spies or start a crackdown against them.” The prospects for a free press in the country don’t look any better. Peter Tiani, a journalist for Le Vrai Journal, was arrested in November and faces a one-year jail term on defamation charges for reporting that a large sum of money was stolen from the home of Bruno Tshibala, the country’s prime minister. Tiani became a target because he reported on the second most powerful man in the DRC, Muyembe says.

“Even journalists who don’t explicitly view the government in a favourable way — those who aren’t necessarily negative but are neutral, as many are — are presented unfavourably by state media,” Muyembe explains. For those who are explicitly critical, he says, the situation can get even worse. With this in mind, Habari has put together some helpful advice for bloggers and citizen journalists.

Online freedoms too remain under strain in the absence of clear laws on the internet, Muyembe says. “While we do want to see such a law, we are also nervous because it could go in a very bad direction and is open to abuse.” As Habari has reported, the hacking of websites ahead of the election has facilitated both censorship and fake news.

Young Congolese people were at the forefront of calls for Kabila not to seek re-election, and Muyembe and his colleagues are keen to ensure that the voices of the country's youth continue to be heard. Habari took part in Speak, a worldwide campaign organised by the NGO Civicus, in November, which sought to raise awareness and build global solidarity in an era when people around the world are facing increased attacks on their basic freedoms. Habari hosted the Gala of Peace, a meeting between young supporters of different political parties and members of citizen movements, that included theatre and dance as well as discussion.

“This year, the idea was to try to work on uniting people who’ve been divided, whether it’s on the social level or the political level,” Muyembe says. “This has much relevance in the DRC, for the divisions that exist between those people who are pro and anti-regime, between the old and young, between men and women and those of different tribes.”

The DRC is also right now in the middle of one of the worst Ebola outbreaks in its history, exacerbated by the ongoing unrest, making it impossible to transport adequate medical care to those in need. “This crisis is different this time around because it’s happening in a part of the country which has been severely affected by the war — the Kivu province in the east of the country,” Muyembe says. “Because of the war, there is a mass migration of the population there whenever there is an attack, which could turn into a major Ebola crisis as there’s a lot of people moving around.”

Next year will be a busy one for Habari in continuing to cover all of these issues. Going forward, the organisation’s biggest challenge, Muyembe says, is ensuring the project has a future as Habari’s partnership with RNW Media, a Dutch organisation that helps young people make social change, along with the essential funding from this relationship, ends in 2020.

However, becoming an Index on Censorship Fellow offers much hope, Muyembe says. “The award has increased how well-known the project is, and how serious it appears. If we now go to meet someone in Kinshasa to talk about the project, or go to an embassy to try to organise something, we are better received.”

For Habari, the training provided by Index, such as the virtual sessions on reporting on elections, has also been invaluable, Muyembe adds. The next training session, by Protection International in January, will focus on developing security and protection management strategies.

Muyembe says that people are often suspicious of organisations involving young people, but the Index award has made things a little easier in this regard. “Every day, colleagues have been telling me that they need to have a copy of the prize that they receive on their website,” he says. “It’s like a business card.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type="post" max_items="4" element_width="6" grid_id="vc_gid:1545229521275-5925950b-9a87-2" taxonomies="16143"][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Apr 2018 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link="https://youtu.be/qqxJndjCWmg"][vc_column_text]

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The aim of these citizen bloggers is to bear witness to what is happening in every corner of the country, which is plagued by extreme poverty, corruption, and violence.

Congo has been racked by civil war for the last 20 years. According to the International Red Cross, Congo had almost a million new displacements in 2016 because of conflict and armed attacks -- the highest in the world.

The population is also overwhelmingly young. Some 64% of the population in Congo are under 24 and 42.2% under 14. Average life expectancy for men is 47 and 51 for women. The country also receives little international coverage. Newspapers within the country are controlled by political factions, and up until now, radio has been the most reliable source of information.

Against this background, Habari RDC is an incredibly ambitious project led by young, digitally savvy and opinionated Congolese men and women with a belief in free expression and non-violence. For the last year, they have been using the internet and all the technology at their disposal to talk about what their country is really like and how they would like it to be.

“We want to create a society in which young people are tolerant of each other. In which young people are not manipulated by politicians for their personal interests, because young people represent hope for the country. In our societies, young people are unfortunately used and set against each other to serve egotistical old people.We fight for human rights and the participation of young people in the running of the country. We dream of a young president who will work for the country and not a young egoist.” Habari creators told Index.

The site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm, and sexual harassment at work. It is funny, angry, modern: a collection of irreverent, young distinctive Congolese voices, demanding to be heard in the world.

Habari has grown and expanded into an established blogging site and source of activism during 2017, covering a wide range of social and political issues. One of its achievements was encouraging voter registration in Walikale Territory where, in the past, not only has registration been low, but people have disappeared from the register. This eastern part of the country is also very cut off. Habari wrote an article about this on their blogging site and as a result, they reported, a local MP put pressure on the government. In the end, according to Habari, 290,000 people there were registered to vote, including 140,000 women. They also help individuals - for instance raising the plight of a woman who was raped and rejected by her family. And have reported on the suppression of the internet; and the use of road taxes to arm militias.

On their nomination for the Index Awards, Habari creators said, “This award represents for us two things at once: the great honor of a recognition of the work of 100 young Congolese bloggers from 100 different corners of the DRC who want to change the living conditions of their peers by raising their voices thanks to internet . But this award is also a challenge to do more."

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width="stretch_row_content" equal_height="yes" el_class="text_white" css=".vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}"][vc_column width="1/2"][vc_custom_heading text="Support the Index Fellowship." font_container="tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center" use_theme_fonts="yes" link="url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||"][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width="1/2" css=".vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460x490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}"][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type="post" max_items="4" element_width="6" grid_id="vc_gid:1522917883563-1453e0af-5b06-2" taxonomies="10735"][/vc_column][/vc_row]