Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100019″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]In the wake of the 15 July 2016 coup attempt, Turkey has become a “de facto permanent” emergency regime. The state of emergency, which has been extended six times, has become a convenient pretext for the government to crack down on freedom of expression.

The resultant purge has had draconian impacts: 5,822 academics sacked, 189 media outlets shuttered and 319 journalists arrested or prosecuted. The country’s judicial system has been decimated, with 4,560 judges and prosecutors dismissed. The government’s near-complete takeover of the judiciary and its direct defiance of the rule of law has debased freedom of expression in the country.

Examples of how the executive arm of the Turkish government is pulling the strings of the judiciary are not hard to find.

“Public indignation”

On 31 March 2017, the chief judge and two members of the Istanbul 25th High Criminal Court, who ordered the release of 21 journalists, and the prosecutor, who requested the releases, were suspended and later faced a disciplinary hearing. The 21 journalists were kept waiting in a prison van until a new arrest and detention order was issued by another court, which was under an onslaught of attacks from pro-government social media accounts.

Judicial Council deputy president Mehmet Yilmaz explained the reasoning behind the suspension of the judges: “The evidence has not been collected…and the release decision issued…has caused public indignation and harmed public conscience.”

If members of the judiciary can be suspended because their decision has caused “public indignation and harmed public conscience”, this suggests that judges in Turkey are without any protection from external pressures.

In another case, on 31 January 2018, a court ordered the release of Amnesty International’s Turkey chair Taner Kilic, but just hours later another demanded his re-arrest. Amnesty’s secretary general Salil Shetty said: “Over the last 24 hours, we have borne witness to a travesty of justice of spectacular proportions. To have been granted release only to have the door to freedom so callously slammed in his face is devastating for Taner, his family and all who stand for justice in Turkey.”

Taner’s renewed detention came after a decision from the Istanbul trial court to conditionally release him before his trial. However, after the prosecutor appealed, a second court in Istanbul accepted this appeal and quashed Taner’s release.

“I do not know why I was imprisoned a year ago and why I was released”

In another example of government interference, Turkish-German journalist Deniz Yücel, who reported for Die Welt newspaper, was arrested on 27 February 2017 in Istanbul. At the time, Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, summarised the accusations against Yücel saying: “He is not a correspondent; he is a terrorist. … This person hid in German consulate for a month as a representative of PKK, as a German spy. We have recordings, everything. This is the very spy terrorist.”

Erdogan also reportedly said that Yücel would not be released so long as he was the president. Yücel’s detention continued for almost a year without charge.

On the eve of his official trip to Germany on 15 February 2018, prime minister Binali Yildirim responded to protests and open requests from the German government for Yucel’s release. He said: “I think that a development will take place soon.” In a joint press conference with German chancellor Angela Merkel on 15 February 2018, he said: “What is necessary shall be done within the scope of the rule of law; what is required of us is to clear the way for the courts. … I hope that the trial will take place within a short time and a result will be achieved.”

On 16 February 2018 the Istanbul High Criminal Court accepted an indictment against Yücel that sought an 18-year sentence, yet the court also simultaneously ordered his release. Yücel flew to Germany on the same day. No international travel ban was imposed, despite the high sentence the prosecutor was demanding, which is the regular practice in “terror” related cases.

After his release, Yücel reported that he was given a 13 February 2018 ruling by the Third Criminal Peace Judgeship which detailed an order for his continued detention. “I am free despite this. I do not know why I was imprisoned a year ago and why I was released today. Is it not strange? Anyway, it does not matter. After all, I know that neither my jailing — more precisely my being taken as a hostage a year ago — nor my release today is in accordance with the rule of law at all. I know this very well.”

It’s clear that Yücel’s release and ability to leave the country were the result of political deals and the high criminal court was taking orders from the executive branch of government.

“Attempting to overthrow the constitutional order”

Within hours after Yücel’s release, six other individuals, including five journalists, were issued life sentences for “attempting to overthrow the constitutional order”. Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan, Nazli Ilicak, Yakup Şimşek, Fevzi Yazıcı and Şükrü Tuğrul Özsengül were all handed sentences after being convicted of involvement with the attempted coup, despite a clear lack of direct evidence.

“The court decision condemning journalists to aggravated life in prison for their work, without presenting substantial proof of their involvement in the coup attempt or ensuring a fair trial, critically threatens journalism and with it the remnants of freedom of expression and media freedom in Turkey,” said David Kaye, the United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression.

The constitutional court decided on 11 January 2018 that the freedom of expression and liberty of the two journalists Mehmet Altan and Şahin Alpay had been violated. Following the decision, deputy prime minister and government spokesperson Bekir Bozdağ stated on his Twitter account that the constitutional court had overstepped its boundary drawn up by the constitution and legislation. Under pressure from the government, the decisions made in the cases of Alpay and Altan were not implemented by Istanbul courts. This was due to almost the same reasoning as used by the government spokesperson.

Despite the dictum that the court’s decisions are final and binding on the legislative, executive and judicial matters, the courts of the first instance have not implemented the decision.

Another disappointment for the freedom of all arrested journalists

In another case, after an application by journalist Sahin Alpay, the constitutional court delivered the decision on 19 March 2018 that found Alpay’s rights were violated under the European Convention on Human Rights. By contrast, the Istanbul court followed the ruling this time and issued Alpay’s conditional release. Surprisingly, nothing was heard from the executive on this occasion. This development has been regarded by some as the government’s tactical move to avoid a possible European Court of Human Rights ruling on related pending cases to the effect that the constitutional court is not an effective remedy.

Turkish human rights lawyer Kerem Altıparmak tweeted that the Turkish government’s move was intended to send a message to the ECtHR that the constitutional court is a viable domestic remedy. Yaman Akdeniz, another prominent law professor and rights defender, said that ECtHR’s rejection of examination of the cases of journalists relying on the Article 18 of the European Convention on Human Rights is another disappointment for the freedom of all arrested journalists.

“A disgrace to Turkey’s justice system”

On 9 March 2018 a Turkish court sentenced 25 journalists to imprisonment on the grounds of allegedly being members of a terrorist organisation. The prosecutor’s primary evidence was that the journalists had criticised the Turkish government and Erdogan on social media. On these charges, 23 of the accused journalists were given between two and seven years in prison. Nina Ognianova, the Committee to Protect Journalists Europe and Central Asia programme co-ordinator, described the decision as “a disgrace to Turkey’s justice system”. She called on authorities to drop the charges on appeal.

The judiciary’s exposure to outside influences and pressures have turned the Turkish judicial system into a nightmare for journalists, academics, rights defenders, philanthropists and even judges themselves.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524736212391-dfe96d06-6795-2″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Recent developments in Turkey, once seen as a role model for the Muslim world, have shown that concepts such as the rule of law and right to free speech are no longer welcome by the Erdogan government.

With 156 journalists behind bars as of 26 February 2018 and the closing down of more than 150 media outlets by virtue of the state’s of emergency decrees, Turkey is the global leader in suppressing the media. The irony is that Erdogan was once a victim of an earlier oppressive regime in the late 1990s, having been dismissed as mayor of Istanbul, banned from political office and put in prison for three months for inciting religious hatred after he recited part of a poem by the Turkish nationalist Ziya Gokalp at a political rally.

The destruction of the rule of law in Turkey has been in the making since the anti-government Gezi Park protests and corruption probes of 2013. However, the government has made its intentions on the right to free speech crystal clear in the aftermath of the 15 July 2016 coup attempt. Many journalists and writers have been imprisoned over accusations as absurd as spreading subliminal messages to promote the coup.

Some of them — like Die Welt journalist Deniz Yucel — have languished in detention without charge for a year. Yucel was used as a bargaining chip against Germany and was only freed after chancellor Angela Merkel put pressure on the Turkish government. Immediately after he was let out of detention he published a video message in which he said: “I still don’t know why I was arrested and why I have been released.”

Ahmet Sik, another well-known journalist, was imprisoned because of his thorough investigations into the dark sides of the coup attempt. Can Dundar was arrested for publishing about Turkish intelligence’s illegal arms transfers to Syria. He was kept in prison for several months and eventually released on a constitutional court decision in February 2016. He fled the country and currently lives in Germany. Veteran journalists Sahin Alpay and Mehmet Altan, on the other hand, were not so lucky. They had been granted freedom by the constitutional court but a local court refused to implement their release. Recently, the Altan brothers, Mehmet and Ahmed, and another senior journalist, Nazli Ilicak, have been brutally sentenced to aggravated life prison sentences. Examples of the obscene unlawful imprisonment of journalists can go on and on.

The heart of the issue is that Turkish journalists do excellent work. They go to extraordinary efforts to make sure the public is informed about corruption, illegal arms transfers, extrajudicial killings of Kurds and minorities, shady affairs of the ruling party with the judiciary and unanswered questions about the coup attempt. The government doesn’t want to see these issues make headlines, and for defying it many journalists have sacrificed their freedom.

Behind the thin veneer of Turley’s judicial system is the political machine manufacturing countless crimes. After 500 days pretrial detention, Ahmet Turan Alkan, an intellectual and a respected writer, pointed that out by telling a judge: “Your honour, I know you can’t release me because if you decide to do so you will be jailed.”

Turkey’s journalists are faced with a unique problem: if they continue to lay bare the truth for all to see they risk exile or prison. In a normal country, journalists performing at the height of their abilities would be encouraged or rewarded, perhaps not by their governments but by the society as a whole. But not so in Turkey, where the government mouthpieces and politically-aligned media outlets spout the latest propaganda to manipulate Turks. Unfortunately, the majority of people actually believe that most of the arrested journalists are criminals or terror supporters.

This collective hostility to freedom of expression makes Turkey one of the biggest violators of press freedom in the 42 European-area countries Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project monitors; one of the lowest ranking countries in Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index; and deemed “not free” by Freedom House’s evaluation.

It’s not just journalists. Academics, rights defenders, philanthropists and lawyers also face punishment for carrying out their professional responsibilities on behalf of the public. Disclosing the unlawful practices of those in power is all it takes for an individual to find themselves on the wrong side of the bars. As with Alpay and Altan, a court had ordered Taner Kilic, the chairman of Amnesty Turkey, to be released from detention, but the prosecutor put him back in prison. Kilic and his colleagues are being targeted in retribution for Amnesty International’s work to make the world aware of the inhumane conditions in Turkey’s post-coup attempt era.

The government’s intolerance toward dissenting voices can also be seen in its treatment of university professors, students and others who signed an Academics for Peace petition, which called for an end to violence in the Kurdish region of the country. Hundreds of distinguished academics have found themselves summoned to courtrooms. For taking a stand about the ongoing tragedy in Kurdish cities, the majority of these academics are dehumanised and defamed. They have not only become enemies of the state but enemies of all Turks.

Yes, the government has terrorised ordinary people with the narrative of the “world against great Turkey” and urged them to stand against outspoken figures who are the “spies, traitors and enemies”.

What do the EU and other international organisations do? Mostly expressing their “concern” in different formats such as “great”, “deep” or “serious”. Even the European Court of the Human Rights has not issued a single verdict against Turkey’s post-coup purge which has seen the country become the world’s largest jailer of journalists.

On the same day the Altan brothers were sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison, Tjorbon Jaglan, the secretary general of the Council of Europe was on a two-day visit in Turkey. He didn’t utter a single word about their situation. What else could better fit the definition of the “banality of evil” conceptualised by Hannah Arendt?[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1519832159496-f7b69135-ce98-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91904″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Two of Turkey’s most prominent writers, brothers Ahmet and Mehmet Altan, were sentenced to life in prison on Friday 16 February 2018.

Convicted on groundless charges related to the attempted coup in 2016 against the government led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, these verdicts, the first of their kind, set a devastating precedent for the many other journalists and writers in Turkey who are being tried on similarly spurious charges widely believed to be politically motivated to silence all criticism of Erdoğan.

Since they began last July, I have been present to observe the Altans’ trial and to witness extraordinary violations of due process and the defendants’ rights to a fair trial. They are also emblematic of an unprecedented crackdown on critical voices in a country where the rule of law is in free fall.

The brothers were arrested in the aftermath of the coup attempt under a state of emergency imposed by Erdogan in July 2016 and renewed six times since, which gave him sweeping powers and pushed Turkey closer to authoritarianism. It is hard to overstate the extent of the purge that has taken place: 200 journalists and 50,000 individuals have been arrested. Independent mainstream media have been all but silenced, with over 180 media outlets and publishing houses closed down. Over 150,000 civil servants, journalists and academics, have been summarily dismissed with no effective appeals process or prospect of re-employment. Dozens of the dismissed have committed suicide.

Once arrested, the Altans found themselves in a legal system where the rule of law has been dismantled with terrifying speed since the coup attempt. What judicial independence existed previously was eviscerated as 4,200 judges and prosecutors were summarily dismissed and replaced with political appointees. The legal system itself – parts of which have long been used to judicially harass independent voices – has been transformed wholescale into a system of repression, with the judiciary now playing a central role in the deterioration of free speech and the rule of law itself.

The indictment in the Altans’ case is 247 pages long, and was largely copied and pasted from other indictments, evidenced by a name from another trial mistakenly appearing in the document. The brothers initially faced three consecutive life terms on charges of plotting to overthrow the government, parliament and the constitutional order for their alleged links to a network led by Fethullah Gülen whom the government accuses of orchestrating the attempted coup. These charges were subsequently reduced to just the latter, carrying one ‘aggravated’ life sentence: a sentence without prospect of parole. Like scores of other journalists across the country, the Altans are also accused of supporting multiple additional terrorist groups – groups which are themselves even in conflict with one another.

Throughout the trials there has been scant evidence or detail of the criminal acts the Altans are said to have committed. A key part of the case has centred on their participation in a TV programme on 14 July 2016, the day before the coup attempt, during which they are said to have sent “subliminal messages” to the coup plotters. (In fact, they discussed the fact that there would be elections and that Erdogan might be voted out.) After this “evidence” was ridiculed wholesale in the Turkish media, it was dropped. In a similarly farcical use of evidence, six $1 bills found in Mehmet Altan’s apartment are cited as proof of his support for the coup, though how these could possibly contribute to attempting to overthrowing the constitutional order remains unclear.

Leading QC, Pete Weatherby, characterised the proceedings as a “show trial” in a report for English Bar Human Rights Committee. At a hearing in November 2017, the judge abruptly expelled the entire defence team. Mehmet Altan was left to defend himself with no lawyer present. I had the surreal experience of observing that hearing with his defence team from the court cafeteria via Twitter. On Monday of this week, his lawyer was expelled from court once again, this time for insisting that the recent landmark Turkish Constitutional Court decision on his client’s case be included in the court’s record, to say nothing of it being upheld.

The lower court’s decision to defy this constitutional court decision on Mehmet Altan is itself at the heart of a constitutional crisis unfolding in Turkey. Until 11 January 2018, the constitutional court had exempted itself from deciding any State of Emergency related cases, despite the 100,000 applications pending before it. Then in a landmark decision a month ago, the constitutional court ruled 11-6 that the detention of Mehmet Altan and veteran journalist, Sahin Alpay for over a year constituted violations of their constitutionally protected “right to personal liberty and security” and “freedom of expression and the press”, establishing the way for their immediate release and setting the necessary precedent for the releases of the dozens of other jailed journalists.

In the hours following the decision, however, a criminal court in Istanbul defied the constitutional court ruling declaring the judgement was a “usurpation of authority” and therefore could not be accepted. This language was disturbingly similar to the reaction of the deputy prime minister and government spokesperson, Bekir Bozdağ, who had tweeted this objection to the decision, claiming that the Constitutional Court had “exceeded” its authority.

This political interference was blatantly in violation of the Turkish Constitution, which renders all constitutional court decisions binding on lower courts. The ongoing crisis surrounding the rule of law and separation of powers, which has been growing since the imposition of the state of emergency, has reached its nadir with Friday’s verdict against Mehmet Altan, demonstrating that Turkey’s citizens can have no expectation of an independent or effective legal remedy in their country.

This crisis in Turkey has profound implications for the European human rights system. The Altans’ case, along with those of eight others relating to journalism is pending before the European Court of Human Rights, of which Turkey has been a member since 1954. Their lawyers applied to the European court in November 2016 after continued inaction by the Turkish Constitutional Court and in April 2017, the court accorded priority status to the cases, opening the way for accelerated proceedings. So important are the implications of these cases for freedom of expression in the country as a whole that an unprecedented group intervened before the court including the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and a coalition of international human rights NGOs led by PEN International.

Since those interventions, however, the European court has been silent. As there is no expectation of independent or effective justice in Turkey, Strasbourg is the last hope for justice for the writers – and indeed, for Turkish society as a whole. And there can be no more urgent cases than these for the European court: they concern individuals who have been detained for over eighteen months, solely on the basis of their writing, that is to say for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression and opinion, which is guaranteed under the European Convention of Human Rights, of which the court is guardian.

However, many in Turkey fear that politicking at the highest levels between Turkey and European member states and institutions is delaying this judgement. Indeed it is widely felt that Europe’s relative silence on the journalists cases is provoked by more utilitarian concerns: the EU-Turkey refugee deal for one, military interests in Syria for another. Meanwhile, Theresa May has shown she is more concerned about selling Erdogan fighter jets and securing a post-Brexit free trade agreement than promoting democracy or human rights.

Meanwhile, the European Union and May appear to be sacrificing the very people who have fought for democratic and liberal values in Turkey. One of the great privileges of my time observing these cases over the last 18 months has been to witness historic defences of freedom of expression from journalists in the dock, on trial for their lives for daring to criticise authoritarianism, corruption and human rights abuses. I think of Ahmet Altan’s defiant closing statement to the judge in the prison court this Tuesday, surrounded by 30 heavily armed riot police – “I came here not to be judged but to judge. I will judge those who, in cold blood, killed the judiciary in order to incarcerate thousands of innocent people.”

Europe would do well to take a longer-term view, to uphold the values of democracy and human rights lest we lose Turkey outright to authoritarianism. Political pressure does work: On the same day as the Altans were sentenced, the Turkish-German journalist, Deniz Yucel, was released after a year in detention following talks between German Chancellor Merkel and Turkish PM Yildirim. Political pressure from Germany is also widely credited for the release of ten human rights defenders and Amnesty International staff in October 2017. Much more of this pressure is needed. Other countries like the UK, and political and financial institutions including the EU need to step up and demonstrate the values they profess to hold in their relations with Turkey.

We urge Europe not to abandon the Altans and Turkey’s other jailed journalists. We can only hope for Turkey’s democrats that justice does not come too late. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”3″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1519806559338-3ec987ef-0828-8″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

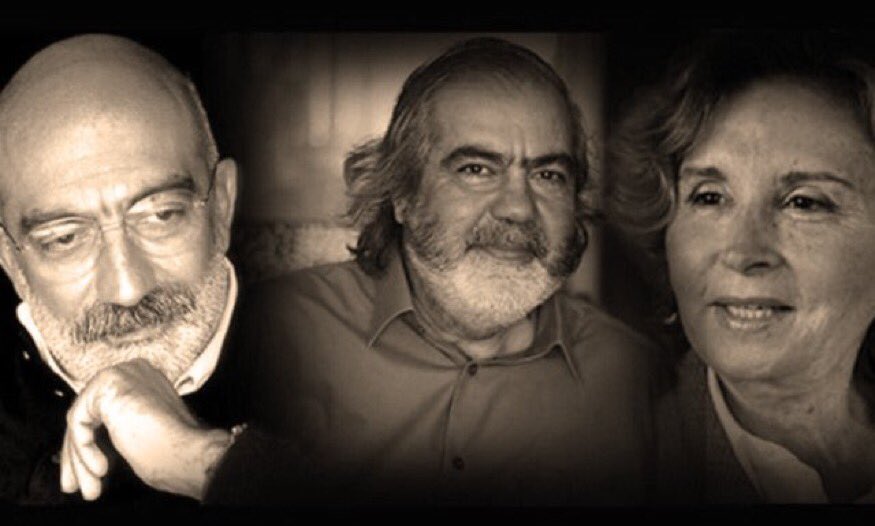

Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan and Nazli Ilcak

Index on Censorship strongly condemns Turkey’s sentencing of six defendants — including journalists Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan and Nazli Ilcak — to aggravated life sentences.

“Today’s appalling verdict represents a new low for press freedom in Turkey and sheds light on how the courts might approach other cases concerning the right to freedom of expression. Today we stand in solidarity with all imprisoned journalists and continue to call on the government to drop all charges,” Hannah Machlin, project manager, Mapping Media Freedom, said.

On 16 February 2018, the 26th High Criminal Court of Istanbul sentenced the defendants to life in prison over allegations related to the attempted July 2016 coup, which Turkish authorities claim was orchestrated by Fettulah Gulen. The charges were detailed in a 247-page long indictment which identifies President Erdogan and the Turkish government as the victims. The defendants were accused of attempting to disrupt constitutional order and inserting subliminal messages into broadcasts.

Ahmet Altan is a novelist, journalist and former editor in chief of the shuttered Taraf daily. His brother, Mehmet Altan is a columnist and professor. Nazli Ilcak is a journalist, writer and former party deputy. The other defendants were Fevzi Yazıcı, who was head of visual at Zaman; Yakup Simşek, who worked in Zaman’s advertising department; Sükrü Tuğrul Ozşengül, a retired police academy teacher who was accused on the basis of a tweet where he predicted there would be a coup.

Today marked the fifth and final hearing in the case which is widely seen as politically motivated.

This is the first conviction of journalists in trials related to the attempted coup.

All three have been detained since 2016 and have denied all charges, citing lack of evidence.

On 19 September 2017 Ahmet Altan testified from Silivri Prison.

Earlier today, Deniz Yucel, a German-Turkish journalist, was released and indicted on charges related to the hacking of the Turkish Energy Minister’s email account . He spent 366 days in prison, including in solitary confinement. Yucel could face up to 18 years in prison.

Turkey is currently the largest jailer of journalists in the world with 153 media workers still behind bars in Turkey.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”2″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1518794983391-6bd72ea1-eea5-5″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]