Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

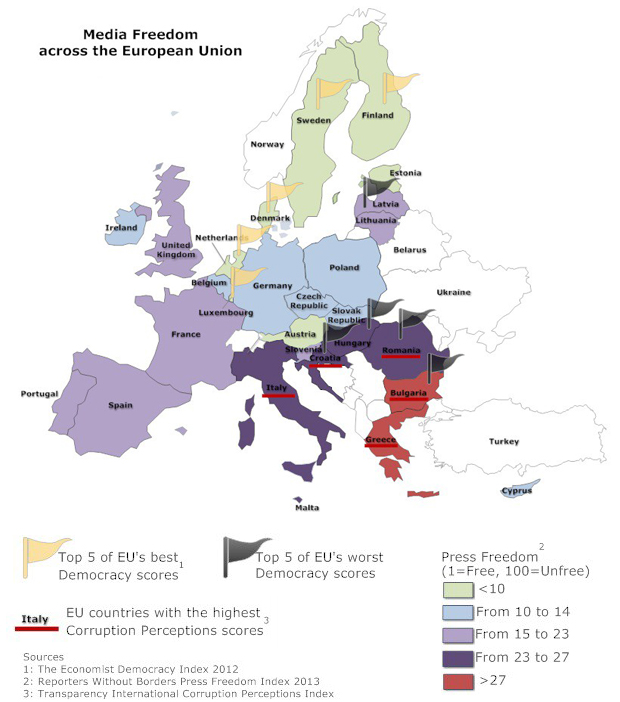

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Since the entering into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, which made the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights legally binding, the EU has gained an important tool to deal with breaches of fundamental rights.

The Lisbon Treaty also laid the foundation for the EU as a whole to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights. Amendments to the Treaty on European Union (TEU) introduced by the Lisbon Treaty (Article 7) gave new powers to the EU to deal with state who breach fundamental rights.

The EU’s accession to the ECHR, which is likely to take place prior to the European elections in June 2014, will help reinforce the power of the ECHR within the EU and in its external policy. Commission lawyers believe that the Lisbon Treaty has made little impact, as the Commission has always been required to assess whether legislation is compatible with the ECHR (through impact assessments and the fundamental rights checklist) and because all EU member states are also signatories to the Convention.[1] Yet external legal experts believe that accession could have a real and significant impact on human rights and freedom of expression internally within the EU as the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) will be able to rule on cases and apply European Court of Human Rights jurisprudence directly. Currently, CJEU cases take approximately one year to process, whereas cases submitted to the ECHR can take up to 12 years. Therefore, it is likely that a larger number of freedom of expression cases will be heard and resolved more quickly at the CJEU, with a potential positive impact on justice and the implementation of rights in the EU.[2]

The Commission will also build upon Council of Europe standards when drafting laws and agreements that apply to the 28 member states. Now that these rights are legally binding and are subject to formal assessment, this may serve to strengthen rights within the Union.[3] For the first time, a Commissioner assumes responsibility for the promotion of fundamental rights; all members of the European Commission must pledge before the Court of Justice of the European Union that they will uphold the Charter.

The Lisbon Treaty also provides for a mechanism that allows European Union institutions to take action, whether there is a clear risk of a “serious breach” or a “serious and persistent breach”, by a member state in their respect for human rights in Article 7 of the Treaty of the European Union. This is an important step forward, which allows for the suspension of voting rights of any government representative found to be in breach of Article 7 at the Council of the European Union. The mechanism is described as a “last resort”, but does potentially provide leverage where states fail to uphold their duty to protect freedom of expression.

Yet within the EU, some remained concerned that the use of Article 7 of the Treaty, while a step forward, is limited in its effectiveness because it is only used as a last resort. Among those who argued this were Commissioner Reding, who called the mechanism the “nuclear option” during a speech addressing the “Copenhagen Dilemma” (the problem of holding states to the human rights commitments they make when they join). In March 2013, in a joint letter sent to Commission President Barroso, the foreign ministers of the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark and Germany called for the creation of a mechanism to safeguard principles such as democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The letter argued there should be an option to cut EU funding for countries that breach their human rights commitments.

It is clear that there is a fair amount of thinking going on internally within the Commission on what to do when member states fail to abide by “European values”. Commission President Barroso raised this in his State of the Union address in September 2012, explicitly calling for “a better developed set of instruments” to deal with threats to these rights.

This thinking has been triggered by recent events in Hungary and Italy, as well as the ongoing issue of corruption in Bulgaria and Romania, which points to a wider problem the EU faces through enlargement: new countries may easily fall short of both their European and international commitments.

Full report PDF: Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Footnotes

[1] Off-record interview with a European Commission lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).

[2] Interview with Prof. Andrea Biondi, King’s College London, 22 April 2013.

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.

Writers include the Bishop of Bradford, Salil Tripathi, Samira Ahmed and Kaya Genc. There’s an interview with Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti ahead of the opening of her new play, and 10 years after Behzti; while cartoonist Martin Rowson writes and draws about how comedy and religious offence come into conflict. Natasha Joseph writes from South Africa on why some portraits of President Zuma made him see red. Alexander Verkhovsky discusses the new blasphemy law in Russia, and former BBC mobile editor Jason DaPonte discusses why computer games are not all bad.

As part of the special report, writer Brian Pellot goes online with the Mormons to see how they use technology to talk to the unconverted, and asks if online chats will replace missions. Germans have been outraged by the revelations about US and UK surveillance, now they have plans to do something different to put a stop to snooping in the future, Sally Gimson reports. From Brazil, Ronaldo Pelli looks at the reaction to people practising religions of African origin, and investigative writer and author of Fast Food Nation Eric Schlosser talks about the threats to investigative journalism now and in the future.

Also in this issue:

Padraig Reidy on flags, controversy and Northern Ireland

Xiao Shu on the Chinese crackdown on the New Citizens’ Movement

Kaya Genc on the rise of a new type of media in Turkey

Urooj M, a former DJ on a Pakistani FM radio channel, also a film aficionado, was incredulous when she found the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) had blocked the Internet Movie Database (IMDb).

She tweeted: “SERIOUSLY #PAKISTAN, WHY ON EARTH WOULD YOU BAN #IMDB!!! COME ON, SERIOUSLY!!!???!!!! #FirstYoutubeNowIMDB #WTF.”

This widely used online entertainment news portal, a prominent source of reliable news and box office reports regarding films, television programmes and video games from all over the world, was blocked on 19 November, but the ban was lifted by 22 November.

Pakistan is notorious for blocking websites. It has banned more than 4,000 websites for what it considers objectionable material, including YouTube, in 2012 for a film that was deemed blasphemous by Muslims around the world. In 2011, in a particularly ill-thought-out move it announced censoring text messages containing swear words. In 2010, after a decision by the Lahore High Court, Facebook was blocked as a reaction to the ‘Everybody Draw Muhammad’ page that was seen as offensive to the prophet.

Users were given no reason for this sudden and selective ban. However, Omar R. Quraishi, a journalist had tweeted: “PTA official declined to give specific reason for ban on IMDB – said is placed for 3 reasons: “anti-state”, “anti-religion”, “anti-social”.

While these “targeted bans” are small irritants in his life, as he can easily by pass them, Ali Tufail, 26, a Karachi-based lawyer, finds them wrong on principle as he sees them infringing upon the fundamental rights of the citizen as given in Article 19 and 19 A of Pakistan’s Constitution.

He said the government must give users sound “reasons” why they block a certain website and “what benchmarks or what standards are used to come to the decision to enforce these sudden bans” and if there is a committee that takes these decisions, “we must be told who these people are.”

The same was endorsed by Nighat Dad of Digital Rights Foundation (DRF). “We strongly oppose any form of censorship employed on citizens, curbing their basic right to information.”

However, netizens believe the ban was enforced to block the movie trailer for The Line of Freedom, a film that highlights the issue of the crises in Balochistan province showing Baloch separatists abducted by Pakistani security agencies without charges in a bid to stamp out rebellion.

“Our team did a quick survey with the help of tweeters around the country,” said Dad. “We checked various other movie titles but only Line of Freedom seemed to be blocked on IMDb and several other websites were accessible otherwise.” The DRF termed it an “unprecedented event” because the government had “used all sorts of means to curb the dissidents’ views” from Balochistan.

“I didn’t even know there was a movie by this title which was giving the government so much heartburn and so I just had to see what was so unsavoury that the government had to block the entire website,” said Dad who watched the whole 30 minutes or so of it by circumventing the various firewalls. “This is what happens, when you forcibly close the internet, word gets around and people get curious!”

Malik Siraj Akbar, editor of the online Baloch Hal, who sought asylum in the United States, is not surprised at the ban. His own newspaper was blocked in November 2010 and even now the ban has not been completely lifted, he says. “Since 2010, it has been available in some parts of the country and not others and access has not been very consistent,” he said adding there were hundreds of other Baloch websites, “mostly those supportive of the nationalists that have been blocked”.

But Tufail added: “This is one battle which the government would find difficult to win as newer, maybe more objectionable [to Pakistani state] websites, will keep popping up which they would never be able to keep pace with,” terming such bans an “exercise in futility”.

There could be some truth in the story of the ban on the Baloch film. Because their voices remain unheard, several family members made a 700km journey on foot from Quetta to Karachi to see if that would make a difference.

Naziha Syed Ali, a journalist at English-language daily Dawn, had recently visited Awaran, a stronghold of the separatists in Balochistan, which had been badly affected by the earthquake on September 24. She said she got a sense of “hostility expressed mainly towards the army and paramilitary rather than Pakistan per se. Then again, the army is seen as a symbol of the country, so it’s pretty much the same thing.”

Ali said “More than fear, they don’t want to take help from what they see as an occupation force.”

According to her the “feelings of alienation have been greatly exacerbated by the issue of the missing people and the kill-and-dump tactics”.

In addition, while Ali found there to be “sufficient food for now”, there was dire need for health services and proper shelter “as the tents that have been distributed are not warm enough for winter”.

The problem is the army is not allowing international and local non-governmental organisations to carry out any relief work there. Instead, the charities run by religio-political organisations and even banned outfits are seen freely roaming about. For years, the state has kept a stony silence over the issue of the disappearances of the Baloch nationalists. Rights group say if the state lets the various organisations into the region, their dark secrets about grave human rights abuses, for now a national shame, may become a problem for it on the international front.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

The rules India makes for its online users are highly significant – for not only will they apply to 1 in 6 people on earth in the near future as more Indians go online, but as the country emerges as a global power they will shape future debates over freedom of expression online.

India is the world’s largest democracy and protects free speech in its laws and constitution.[1] Yet, freedom of expression in the online sphere is increasingly being restricted in India for a number of reasons– including defamation, the maintenance of national security and communal harmony, which are chilling the free flow of information and ideas. Many of the most restrictive laws and technical means used to enforce these restrictions are recent developments that have undermined India’s record on freedom of expression. A mix of social and political pressure, alongside the terrorist attacks in Mumbai in 2008, has led to this decline, but civil society is beginning to push back.

This paper explores the main digital issues and challenges affecting freedom of expression in India today and offers some recommendations to improve digital freedom in the country.

Constraints on digital freedom have caused much controversy and debate in India, and some of the biggest web host companies, such as Google, Yahoo and Facebook, have faced court cases and criminal charges for failing to remove what is deemed “objectionable” content. The main threat to free expression online in India stems from specific laws: most notorious among them the 2000 Information Technology Act (IT Act) and its post-Mumbai attack amendments in 2008 that introduced new regulations around offence and national security.

New regulations introduced in 2011 oblige internet service providers to take down content within 36 hours of a complaint, whether made by an individual, organisation or government body, or face prosecution. This is problematic in many ways: it makes intermediaries liable for content which they did not author on websites and platforms which they may not control and encourages them to monitor and pre-emptively censor online content, which leads to the excessive censorship of content.

Meanwhile, the arrest and prosecution of citizens who have posted content deemed “grossly harmful”, “harassing”, or “blasphemous” has multiplied. Censorship through the criminalisation of online speech and social media usage is troubling, especially when it affects legitimate political comment or harmless content.

Other issues addressed in this paper include how individual states and the national government of India restricts online communications using filters, and increasingly engages in mass surveillance, which can chill freedom of expression. One of the most pressing challenges to digital freedom remains India’s use of network shutdowns in certain regions, it is claimed, in order to prevent public disorder.

Ensuring access to the digital world remains a national challenge. With only 10 percent of the Indian population online today, there may be a billion new Indian netizens online in the future. How India enables this to happen will be a major challenge. While India is an increasingly influential player in global internet governance, now is a critical time to analyse its domestic regulations and policies that will shape the path not only for the people of India but also for regional neighbours and emerging democratic powers.

This paper is divided into the following chapters: online censorship; the criminalisation of online speech and social media; surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data; access to digital; and India’s role in global internet debates.

The online censorship chapter looks at intermediary liability and the issue of state and corporate censorship mainly via takedown requests and filtering and blocking policies. The criminalisation of online speech chapter covers the prosecution of Indian citizens who post content on the net, including on social media.

The surveillance chapter looks at the recent revelations on the extraordinary extent of domestic surveillance online, and how it contributes to chilling free speech online. It also looks at privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data. The access chapter covers obstacles and opportunities in expanding digital access across the country.

Finally, the chapter on India’s role in global internet debates looks at India’s positioning in the current debates that will result in potentially significant changes to net governance in the next two years.

This policy paper is based on research from London and a series of interviews conducted between June and October 2013 with a range of interviewees from civil society, internet businesses, political figures and journalists.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To end internet censorship and provide a safe space for digital freedom, Indian authorities must:

• Stop prosecuting citizens who express legitimate opinions in online debates, posts and discussions;

• Revise takedown procedures, so that demands for online content to be removed do not apply to legitimate expression of opinions or content in the public interest, so not to undermine freedom of expression;

• Reform IT Act provisions 66A and 79 and takedown procedures so that content authors are notified and offered the opportunity to appeal takedown requests before censorship occurs;

• Stop issuing takedown requests without court orders, an increasingly common procedure;

• Lift restrictions on access to and functioning of cybercafés;

• Take better account of the right to privacy and end unwarranted digital intrusions and interference with citizens’ online communications;

• Maintain their support for a multistakeholder approach to global internet governance.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Article 19 of the Indian Constitution protects freedom of speech and expression. Government of India, ‘The Constitution of India,’ as modified up to the 1st December 2007, Article 19. (1)(a) ‘All citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression’ http://lawmin.nic.in/ accessed on 23 September 2013.