Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Gay rights campaigners should be wary of calling for censorship of a “sexual purity” app, says Sean Gallagher

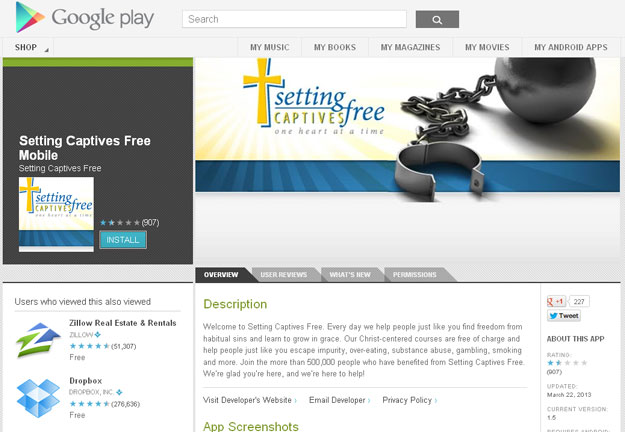

All Out, a gay rights organisation, is behind an online petition calling on Google to remove an app called Setting Captives Free from its Play store. The group claims that Apple removed the app from iTunes after “just 24 hours”.

The app springs from a “non-denominational ministry which teaches the biblical principles of freedom in Jesus Christ” founded by Mike Cleveland. It connects users with the ministry’s free 60-day courses aimed at ridding them of their “habitual sins” like over-eating, substance abuse, gambling, smoking and impurity. One of the courses explores “sexual purity”.

All Out’s position is that these so-called “gay cures” “cause terrible harm to lesbian, gay, bi, and trans people, or anyone forced to try to change who they are or who they love”. The organisation should be applauded for its fight against bigotry and intolerance.

But their misguided petition — which has drawn 154,299 supporters as of this writing — crosses a very clear line into censorship.

Arguments for the public good were previously used to silence gay and lesbian people. We should be wary of even well intentioned censorship. If we apply All Out’s stand to all apps, we’d need to get Google to drop Manhunt, Grindr or other hookup apps that have the potential to harm gay men by spreading disease — a link made by New York authorities during a recent outbreak of meningitis.

There are over 700K apps on Google Play as of October 2012. Downloading is a choice.

Sean Gallagher is Editor, Online and News at Index on Censorship. He tweets from @seangallagherla

A reader has contacted Index on Censorship to point out that the website Transhumanity.net has been blocked on his 02 phone.

We’ve checked, and he’s right — the site is blocked as “pornography”.

It’s a little difficult to see why: there’s certainly nothing I’d consider pornographic on the site.

Transhumanism is an essentially utopian concept, which believes in harnessing technology and theory to create better lives for humans, free from hunger and disease and the general biological decay to which, in the end, we all succumb.

What we can guess is causing the trouble for Transhumanity.net is discussions on gender. Transhumanity.net says it is interested in “multiplicity of genders” among other things. Which makes sense; any wide-ranging discussion about the future of humanity is going to involve discussion about the future of sexuality, gender and identity. But these topics could trigger filters merely because of the use of certain words.

This week, Culture Secretary Maria Miller will be holding meetings to discuss filtering of web content. But this case demonstrates just one problem with the current discussion in the UK: if we accept the default blocking of pornography, how do we avoid confusion between sexual content and discussions of sexuality and gender?

Let us know if you’ve had any experience of gender topics being blocked.

Once labelled the “enemy of the internet” — Tunisia has made tremendous strides in the past two years towards opening up the internet. Still, the country continues to face challenges in its road to expanding freedom online. Afef Abrougui reports

Tunisia is scheduled to host the third annual Freedom Online Coalition conference next week (17-18 June). The country became part of the coalition in September 2012, joining 17 other countries pledged to advance internet freedom.

A great leap forward

In a press conference last September, Tunisia’s ICT minister Mongi Marzoug announced the end of online filtering — killing “Ammar 404” (the nickname given to the country’s filtering system by its netizens).

Just this month, CEO of the Tunisian Internet Agency (ATI) Moez Chakchouk announced that ATI won an appeal against filtering of adult content. The case dates back to May 2011, when a primary court ordered the agency to filter X-rated websites on the ground that they represent a “threat to minors and the values of Islam.” After losing the appeal in August 2011, the Cassation Court quashed the filtering verdict and referred the case back to the Court of Appeal in February 2012.

“This is not about pornography; it’s a matter of principle. In post-revolutionary Tunisia, we are determined to break with the former regime’s censorship practices”, Chakchouk wrote for Index on Censorship magazine in December 2012.

Under the autocratic rule of now ousted President Zeine el Abidin Ben Ali, the ATI enforced government requests for content filtering — even though the country has never had a law requiring the agency to do so. The ATI’s recent win will only help reinforce its role as a neutral internet exchange point.

Threatened Freedom

Despite ending its filtering practises, internet freedom remains threatened by legislation inherited from the era of Tunisia’s dictatorship. For instance, laws that make ISPs liable for third-party content, obliging them to monitor and take down material deemed to violate public order and “good morals” remain on the books. While this particular law has not been enforced post-Ben Ali, other relics from Tunisia’s dictator days have been used to prosecute bloggers.

On 29 May, Hakim Ghanmi, author of the blog Warakat Tounsia, stood trial before a military court for a post he made on 10 April, critical of the administration of a military hospital in Gabes, a city in the south of Tunisia. Ghanmi alleged that his sister-in-law was denied medical treatment by the hospital director, despite having an appointment. The blogger has been accused of “undermining the reputation of the army” (article 91 of the Code of Military Justice), “disturbing others through public communication networks” (article 86 of the Telecommunications Code), and “defamation of a public official” (article 128 of the Penal Code) following a complaint lodged by the hospital director. He currently faces up to three years in prison, and his trial is set to resume on 3 July.

Last year, a court convicted Jabeur Mejri and Ghazi Beji to seven and a half years in prison over publishing content deemed to be offensive to Islam online, under article 86 of the Telecommunication Code, and article 121(3) of the Penal Code which bans the publication of content “liable to cause harm to the public order.” On 12 June, Courrier de l’Atlas reported that Beji, who was sentenced in absentia, has now obtained political asylum in France. Mejri, however, remains in prison after losing appeal at the Cassation Court on 26 April.

If Tunisia is serious about serving as a model of internet freedom in the region and guaranteeing freedom of expression, legal reforms are urgently needed. Adopting a constitution that enshrines free speech — in accordance with the country’s obligations under Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) — is equally fundamental.