Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

On 7 March, a US federal judge granted the government’s motion to dismiss the majority of its criminal case against journalist Barrett Brown. The 11 dropped charges, out of 17 in total, include those related to Brown’s posting of a hyperlink that led to online files containing credit card information hacked from the private US intelligence firm Stratfor.

Brown, a 32-year old writer who has had links to sources in the hacker collective Anonymous, has been in pre-trial detention since his arrest in September 2012 – weeks before he was ever charged with a crime. Prior to the government’s most recent motion, he faced a potential sentence of over a century behind bars.

The dismissed charges have rankled journalists and free-speech advocates since Brown’s case began making headlines last year. The First Amendment issues were apparent: are journalists complicit in a crime when sharing illegally obtained information in the course of their professional duties?

“The charges against [him] for linking were flawed from the very beginning,” says Kevin M Gallagher, the administrator of Brown’s legal defense fund. “This is a massive victory for press freedom.”

At issue was a hyperlink that Brown copied from one internet relay chat (IRC) to another. Brown pioneered ProjectPM, a crowd-sourced wiki that analysed hacked emails from cybersecurity firm HBGary and its government-contracting subsidiary HBGary Federal. When Anonymous hackers breached the servers of Stratfor in December 2011 and stole reams of information, Brown sought to incorporate their bounty into ProjectPM. He posted a hyperlink to the Anonymous cache in an IRC used by ProjectPM researchers. Included within the linked archive was billing data for a number of Statfor customers. For that action, he was charged with 10 counts of “aggravated identity theft” and one count of “traffic[king] in stolen authentication features”.

On 4 March, a day before the government’s request, Brown’s defence team filed its own 48-page motion to dismiss the same set of charges. They contended that the indictment failed to properly allege how Brown trafficked in authentication features when all he ostensibly trafficked in was a publicly available hyperlink to a publicly available file. Since the hyperlink itself didn’t contain card verification values (CVVs), Brown’s lawyers asserted that it did not constitute a transfer, as mandated by the statute under which he was charged. Additionally, they argued that the hyperlink’s publication was protected free speech activity under the First Amendment, and that the application of the relevant criminal statutes was “unconstitutionally vague” and created a chilling effect on free speech.

Whether the prosecution was responding to the arguments of Brown’s defense team or making a public relations choice remains unclear. The hyperlink charges have provoked a wave of critical coverage from the likes of Reporters Without Borders, Rolling Stone, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the New York Times, and former Guardian columnist Glenn Greenwald.

Those charges were laid out in the second of three separate indictments against Brown. The first indictment alleges that Brown threatened to publicly release the personal information of an FBI agent in a YouTube video he posted in late 2012. The third claims that Brown obstructed justice by attempting to hide laptops during an FBI raid on his home in March of that year. Though he remains accused of access device fraud under the second indictment, his maximum prison sentence has been slashed from 105 years to 70 in light of the dismissed charges.

While the remaining allegations are superficially unrelated to Brown’s journalistic work, serious questions about the integrity of the prosecution persist. As indicated by the timeline of events, Brown was targeted long before he allegedly committed the crimes in question.

On 6 March 2012, the FBI conducted a series of raids across the US in search of material related to several criminal hacks conducted by Anonymous members. Brown’s apartment was targeted, but he had taken shelter at his mother’s house the night prior. FBI agents made their way to her home in search of Brown and his laptops, which she had placed in a kitchen cabinet. Brown claims that his alleged threats against a federal officer – as laid out in the first indictment, issued several months later in September – stem from personal frustration over continued FBI harassment of his mother following the raid. On 9 November 2013, Brown’s mother was sentenced to six months probation after pleading guilty to obstruction of justice for helping him hide the laptops – the same charges levelled at Brown in the third indictment.

As listed in the search warrant for the initial raid, three of the nine records to be seized related to military and intelligence contractors that ProjectPM was investigating – one of which was never the victim of a hack. Another concerned ProjectPM itself. The government has never formally asserted that Brown participated in any hacks, raising the question of whether a confidential informant was central to providing the evidence used against him for the search warrant.

“This FBI probe was all about his investigative journalism, and his sources, from the very beginning,” Gallagher says. “This cannot be in doubt.”

In related court filings, the government denies ever using information from an informant when applying for search or arrest warrants for Brown.

But on the day of the raids, the Justice Department announced that six people had been charged in connection to the crimes listed in Brown’s search warrant. One, Hector Xavier Monsegur (aka “Sabu”), had been arrested in June 2011 and subsequently pleaded guilty in exchange for cooperation with the government. According to the indictment, Sabu proved crucial to the FBI’s investigation of Anonymous.

In a speech delivered at Fordham University on 8 August 2013, FBI Director Robert Mueller gave the first official commentary on Sabu’s assistance to the bureau. “[Sabu’s] cooperation helped us to build cases that led to the arrest of six other hackers linked to groups such as Anonymous,” he stated. Presuming that the director’s remarks were accurate, was Brown the mislabeled “other hacker” caught with the help of Sabu?

Several people have implicated Sabu in attempts at entrapment during his time as an FBI informant. Under the direction of the FBI, the government has conceded that he had foreknowledge of the Stratfor hack and instructed his Anonymous colleagues to upload the pilfered data to an FBI server. Sabu then attempted to sell the information to WikiLeaks – whose editor-in-chief, Julian Assange, remains holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London after refusing extradition to Sweden for questioning in a sexual assault case. Assange claims he is doing so because he fears being transferred to American custody in relation to a sealed grand jury investigation of WikiLeaks that remains ongoing. Though Sabu’s offer was rebuffed, any evidence linking Assange to criminal hacks on US soil would have greatly strengthened the case for extradition. It was only then that the Stratfor data was made public on the internet.

During his sentencing hearing on 15 November 2013, convicted Stratfor hacker Jeremy Hammond stated that Sabu instigated and oversaw the majority of Anonymous hacks with which Hammond was affiliated, including Stratfor: “On 4 December, 2011, Sabu was approached by another hacker who had already broken into Stratfor’s credit card database. Sabu…then brought the hack to Antisec [an Anonymous subgroup] by inviting this hacker to our private chatroom, where he supplied download links to the full credit card database as well as the initial vulnerability access point to Stratfor’s systems.”

Hammond also asserted that, under the direction of Sabu, he was told to hack into thousands of domains belonging to foreign governments. The court redacted this portion of his statement, though copies of a nearly identical one written by Hammond months earlier surfaced online, naming the targets: “These intrusions took place in January/February of 2012 and affected over 2000 domains, including numerous foreign government websites in Brazil, Turkey, Syria, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Nigeria, Iran, Slovenia, Greece, Pakistan, and others. A few of the compromised websites that I recollect include the official website of the Governor of Puerto Rico, the Internal Affairs Division of the Military Police of Brazil, the Official Website of the Crown Prince of Kuwait, the Tax Department of Turkey, the Iranian Academic Center for Education and Cultural Research, the Polish Embassy in the UK, and the Ministry of Electricity of Iraq. Sabu also infiltrated a group of hackers that had access to hundreds of Syrian systems including government institutions, banks, and ISPs.”

Nadim Kobeissi, a developer of the secure communication software Cryptocat, has levelled similar entrapment charges against Sabu. “[He] repeatedly encouraged me to work with him,” Kobeissi wrote on Twitter following news of Sabu’s cooperation with the FBI. “Please be careful of anyone ever suggesting illegal activity.”

While Brown has never claimed that Sabu instructed him to break the law, the presence of “persons known and unknown to the Grand Jury,” and whatever information they may have provided, continue to loom over the case. Sabu’s sentencing has been delayed without explanation a handful of times, raising suspicions that his work as an informant continues in ongoing federal investigations or prosecutions. The affidavit containing the evidence for the March 2012 raid on Brown’s home remains under seal.

In comments to the media immediately following the raid, Brown seemed unfazed by the accusation that he was involved with criminal activity. “I haven’t been charged with anything at this point,” he said at the time. “I suspect that the FBI is working off of incorrect information.”

This article was posted on March 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Photo illustration: Shutterstock

In February, thousands of websites urged their users to help stop web monitoring. The Day We Fight Back, led by American lobby group Demand Progress, condemned NSA Internet surveillance and remembered Aaron Swartz, opponent of the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), who hanged himself last year when faced with fifty years in prison for downloading academic texts. Swartz, from whom courts sought $1m in fines, is synonymous today with US clashes over online justice, but the subject is a global one. Germany, where I moved just before SOPA hit the news, offers a frightening glimpse at what happens when copyright policing trumps privacy.

I moved to Berlin in September 2011, as the German Pirate Party won its way into the city state’s assembly. Papers bewildered by this breakthrough named the party, all of whose candidates gained seats, the new rebels in national politics, noting their platform reached young, deprived and disaffected voters. I spent October in a part of town with plenty, renting a cupboardlike room while seeking somewhere longer term. The other tenants, a Barcelonian tour guide and science student from Berlin subletting empty space for cash, already knew each other. Nocturnal, inconsiderate and antisocial, the new kid scared of trying to make friends, I wasn’t a good flatmate, and left amid severe awkwardness.

At my new address, the scientist – passive-aggressively polite – told me I had to sign a retroactive rental contract. This could easily have been done by email — when he asked to meet, I should have smelled a rat, but obliged outside a supermarket in November, not stopping to wonder why both ex-flatmates turned up. “While you were here,” he said once papers were filled out, “you used BitTorrent?”

I had, I said, like almost all my friends. Filesharing was in my eyes like speeding on the motorway, an illegality most practised and few cared about. “We all do it”, the Barcelonian said, who seemed to have come reluctantly.

The scientist produced a further wad of fine-print forms. “We got sued”, he told me, “by the music industry.”

This wasn’t quite true. The document he held was an Abmahnung, a razor-edged cease-and-desist letter of German law, which lets lawyers bill recipients for time spent drafting them. The aim is to curb legal costs for poorer plaintiffs, but since other laws allow solicitors to act without instruction, firms monitor the web (often via private companies), posting them en masse to copyright infringers as a profit-making scheme; 500,000 people, reports claim, receive them yearly. Whoever issued one to my flat sought money for themselves – rights holders almost certainly weren’t briefing them.

I didn’t know any of this back then. In England, where no such business model thrives, being caught filesharing was unheard of. When I moved there, I had no idea of the German situation, and wasn’t ready for the consequences. Ambushed by ex-flatmates, intimidated and off-balance, I didn’t just sign forms admitting I’d downloaded one major artist’s album – I signed others the scientist handed me stating I’d bootlegged files I hadn’t. These accounted for nine tenths of what I later had to pay — at current exchange rates, close to £2000.

The film and record the forms named, presumably, were torrented by someone else in the flat. I’d never heard of them, and with ten minutes to think straight would have realised that – but thinking straight when bombshells land, not least while scanning foreign legalese, is difficult. Half on autopilot, half assuming I knew them by other names, I signed the papers in the bedlam of the moment. “Um ehrlich zu sein”, the scientist said once I realised my mistake, “glaube ich dir nicht.” To be honest, I don’t believe you.

If I didn’t pay the four figure sum the Abmahnung called for, the firm behind it would file suit – in which case, he said, he’d forward them what I signed and I should find a lawyer. Had I hired one, I might have been cleared or at least fined less. Specialists can haggle numbers down – typically, says Cologne solicitor Christian Solmecke, “by about half”. The trouble, which led me to pay up, was that this wouldn’t be much better.

Abmahnung victims, the Pirate Party states, are often “seriously intimidated”. A court case at the best of times is hard — this was my year out as a language student, my German was nowhere near strong enough, and the thought terrified me. Inflated study grants for life abroad arrived, by chance, just as the crisis hit, and my finances were fortunately healthy even after paying out, but a lawyer wouldn’t have been cheap. Solmecke’s firm charges €400-500 to represent its clients (£300-413), seemingly a mainstream rate, and legal bills stack up.

Not all those affected are BitTorrent users. Hamburg resident Karin Gross was charged €300 when an Abmahnung alleged she’s downloaded an obscure illegal media program which bore all the marks of infectious malware; firms like Kiel lawyer Lutz Schroeder’s make thousands threatening those in her position. “You either get ripped off by some lawyer sending you an Abmahnung”, she told the press, “or you have to hire another lawyer who costs just as much.”

Others pay for honest oversights. Pensioners Lydia and Heinz Paffrath, who sold their grandchildren’s old toys for them on eBay, were charged over €650 when they accidentally advertised a doll’s wardrobe under the wrong brand name. Canadian exchange student Nina Arbabzadeh, visiting Berlin in 2012, was billed €1200 for downloading Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange, which neither she nor her flatmate had done. A visitor who had, they guessed, had used their wireless with torrent software left on.

It’s true, I torrented a handful of things, in one case getting caught, and that most Abmahnungen go to users who do. Does this justify the fines at hand – more, I noted then, then you’d get for vandalising Berlin’s city trains, and far more than for shoplifting DVDs? I haven’t touched illegal downloads since, and my web use now is hemmed in by a mesh of proxy servers and precautions. Even having sworn off BitTorrent, I’m anxious, second-guessing every click and panicking at German-language post (last month, when an official looking envelope came for my flatmate, I Google-searched advice for half an hour — it turned out she had unpaid speeding tickets.)

“If you’ve nothing to hide, you’ve got nothing to fear”, the snooper’s mantra goes, but it’s more and more impossible to know what will and won’t be punished.

Last July, a Hamburg court capped sums ordered of downloaders at €150, a measure lauded by the press and praised by local activist Anneke Voss as curbing “the Abmahnung industry’s shameless excesses”. The federal Law Against Dubious Business Practices followed in October, applying an admittedly less helpful €1000 limit nationwide. It didn’t stop the biggest wave of Abmahnungen in history, more than 30,000 people getting them in one December week who’d visited RedTube.com, an adult site whose pornographic clips – some, under copyright, uploaded by third parties – are streamed like YouTube videos.

This isn’t even filesharing — users are made to pay up or face a legal fight simply for viewing web pages. It doesn’t matter that the case against them is a flimsy one. Costs plunge many in to crisis even if they win. Torrenters may not be protected either, as the new law waives its cap on fines “if the stated value [lost to rights holders], according to the individual case’s own circumstances, is considerable”. No one knows yet what this means in practice – a lengthy period of wrangling is expected to ensue – but vested interests will no doubt defend their moneymaking prospects.

British and US laws give firms less room to act like this, but it’s clear to those who care that Germany’s status quo is less a triumph of fair play or honesty than a toxic cocktail of profiteering and surveillance. It’s easy to see, post-Swartz and post-Wikileaks, how the assault on piracy might lead down such a road.

If it does, the world will be dragged with it. SOPA, which threatened the wholesale existence of media platforms like YouTube, Flickr and Vimeo, was meant to take worldwide effect. Officials opted to “postpone consideration of the legislation until there is wider agreement”, shelving rather than scrapping the proposals. The act, or the prospect of one like it, still hangs over us. Even that may not be needed. In David Cameron’s Britain, where service providers were ordered last year to block video-sharing sites, the Big Society ideals of web-policing and privatised justice could produce a German style free-for-all if left to run their course.

The internet was made for instant data replication – in other words, for filesharing. Copyright laws weren’t passed with it in mind. On social media this week, you’ve likely witnessed dozens of infringements – photos, gifs, videos, quotations. Clampdowns on piracy, as the German system demonstrates, attack the core idea of the net, scapegoating users for new technology’s inescapable impact. Rights protection has its place, but must be reformed.

This article was posted on March 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Image: @ilya_shepelin/Twitter)

Russian authorities have blocked access to 13 sites connected to “Ukrainian nationalist organisations” on the social media site Vkontakte, Russia’s answer to Facebook.

The Russian General Prosecutor’s Office requested that Roskomnadzor — the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media — block the pages, the body said in a statement Monday. The pages promoted Ukrainian nationalist groups and “contained direct appeals to Russian people to conduct terrorist activities,” the statement read.

There had been reports over the weekend of pages on Vkontakte being blocked, but the message from Roskomnadzor confirms this.

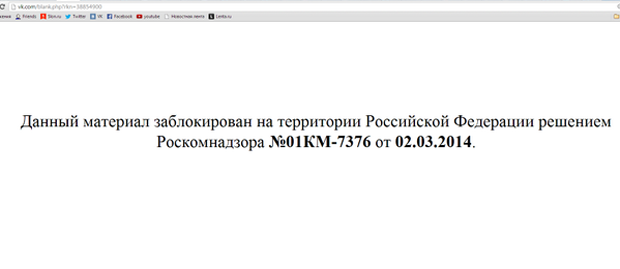

While it is unclear which sites the ban covers, it appears a group connected to the Euromaidan protests is one of them. A screen grab, allegedly from a Euromaidan group, first shared by a journalist from Russian news site slon.ru, read: “This material was blocked on the territory of Russian Federation by a decision by the State Communication Committee” and that the decision had been made on 2 March.

This article was posted on March 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Image: Mahmoud Illean/Demotix)

There should be a special United Nations mandate for protecting the right to privacy, says the Frank La Rue, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression. “I believe that privacy is such a clear and distinct right…that it would merit to have a rapporteur on its own.”

While he pointed out there is some opposition to creating new mandates on economic grounds, he said: “In general If you would ask me, I would say yes, this right deserves a [UN] mandate.” He also called for a coordinated effort from the UN human rights system to deal with the issue of privacy.

The comments came during an expert seminar in Geneva Monday on “The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age” in the aftermath of the mass surveillance revelations.

La Rue said that the right to privacy has not been given enough attention in the past, calling it equal, interrelated and interdependent to other human rights. In particular, he spoke of its connection to freedom of expression and how having or not having privacy can affect freedom of expression.

“Privacy and freedom of expression are not only linked, but are also facilitators of citizen participation, the right to free press, exercise of free opinion, and the possibility of gathering individuals, exercising the right to free association and to be able to criticise public policies.”

He also warned against trying to protect national security at the expense of democracy and human rights, saying: “If we pitch one against the other…I think we’ll end up losing both.”

This echoes the sentiments of his report released in June 2013, which concluded that: “States cannot ensure that individuals are able to freely seek and receive information or express themselves without respecting, protecting and promoting their right to privacy.”

This article was posted on 25 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org