19 Dec 2013 | About Index, Campaigns, Digital Freedom, Press Releases

Index on Censorship is deeply concerned that neither the report nor the recommendations on the NSA prepared by the White House review panel tackles the worldwide mass surveillance carried out by the United States. Index calls on President Obama to take urgent action to respect the right to freedom of expression and privacy of all the world’s citizens, not just those of the United States.

The report from President Barack Obama’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technology is a 300-page tome which includes 46 recommendations – from forcing telecommunications firms to store call data for on demand NSA access, to higher level signoff on surveillance of foreign leaders.

Kirsty Hughes, CEO of Index, said:

“These weak recommendations offer no privacy for non-Americans and only scant protection for foreign leaders. The NSA’s surveillance programmes continue to violate human rights on a massive scale. When Barack Obama decides what reforms to implement in January, he should remember that Americans are not the only people who deserve the right to privacy and free speech. ”

16 Dec 2013 | News and features

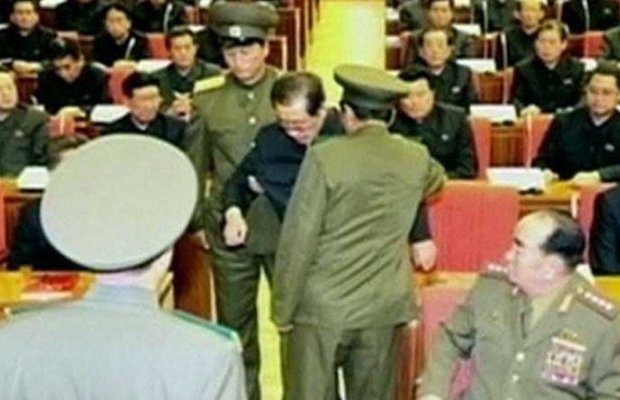

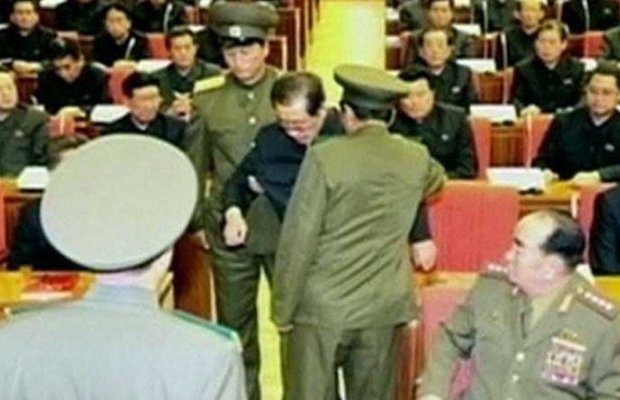

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

“It’s definitely the largest ‘management’ of its online archive North Korea has engaged in since it went online. No question,” Frank Feinstein, North Korea news analyst, told this writer on Sunday (15 December).

The Korean Central News Agency (www.kcna.kp), the state’s main organ, started publishing in its current online form on 1 January, 2012, and had some 39,000 Korean-language articles by mid-December 2013, with many translated into other languages. “Now however there are now no articles in the archive from prior to October 2013, with everything numbered to around 35,000 – or to October this year – gone,” said Feinstein, director of KCNA Watch, which analyses North Korean media for keywords and converts that into visual data to gauge reporting trends. Similar proportions of deletions were true for Korean Workers’ Party paper Rodong Sinmun and www.uriminzokkiri.com.

Just four days passed from the arrest Kim Jong Un’s uncle Jang, which was televised across North Korea, to his execution on 12 December 12. Thereafter the expurgation of any mention of Jang from the state news files took just hours. Following outages that to seemed affect several state online news sources, of some 550 Jang-related Korean articles on www.kcna.kp, Feinstein estimated that by late Friday, “every single one has either been altered, or deleted, without exception”. This included the most anodyne reports such as a 5 October KCNA story about Kim Jong Un visiting a hospital under construction now reads: “He personally named it ‘Okryu Children’s Hospital’ as it is situated in the area of Munsu where the clean water of the River Taedong flows.” But the original had continued: “He was accompanied by Jang Song Thaek, member of the Political Bureau of the CC, the WPK and vice-chairman of the NDC, and Pak Chun Hong, Ma Won Chun and Ho Hwan Chol, vice department directors of the CC, the WPK.”

Other examples are at the KCNA Watch site, and as also observed by North Korea watcher, Martyn Williams at www.northkoreatech.org.

What’s new about the North’s retrospective media management is its scale and that it’s doing it online, before a global audience. “This is North Korea censoring itself to the world – not just to its own citizens…Personally, I can’t believe they could think they’d get away with this sort of revisionism,” said Feinstein.

Nonetheless, the North can sustain its digital Ministry of Truth antics on the World Wide Web by preventing its output from being indexed. ‘It already works on KCNA – Google can’t index it at all. You can’t even link to an article on KCNA,’ said Feinstein, pointing to Google’s entire, paltry record of KCNA’s office in Pyongyang via this link.

It’s not clear even if South Korean intelligence or news agency Yonhap can archive KCNA’s database in its live form. “While North Korea doesn’t understand much about how to successfully operate online, they do understand this much.”

One theory contends that the North publishes different propaganda for internal and external consumption. For sure, North Korean people can only access news produced by the North Korean state, accessing www.kcna.kp through the country’s intranet, but more likely from the state TV, radio or newspapers on station platform hoardings of which obviously none enable access to digital or visual archives. TV has also been noted as adjusted, with a documentary first shown on 7 October 2013 being reshown on 7 December with Jang cut out of shots by adjusted focus and framing.

The upshot is this: “Our party, state, army and people do not know anyone except Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un,” according to the sole English-language article left on KCNA that mentions Jang, a vicious 2,750-word denouncement from 13 December 13. The piece calls Jang “impudent, arrogant, reckless, rude and crafty,” “despicable human scum … worse than a dog,” who, backed by “ex convicts”, had plotted to destroy the economy before “rescuing” the country by military coup and billions earned from hoarded precious metals.

“They are serious about removing him from history,’ said Feinstein, except for passages such as “the era and history will eternally record and never forget the shuddering crimes committed by Jang Song Thaek, the enemy of the party, revolution and people and heinous traitor to the nation,” which concludes the KCNA piece. Meanwhile, “Rodong Simnun no longer knows Jang as anything other than a traitor,” tweeted Korea historian and linguist, Remco Breuker.

Traffic to www.kcna.kp has never been higher, even than for the death of Kim Jong Il, as people now follow stories to the source and are captivated by the apparent novelty of North Korea having an online presence, and one that uses such bizarre language. “Once they find KCNA, there’s no going back.” KCNA’s legitimacy as an analytical source for the North Korean state’s views is oft obscured by its saltier reportage.

Outside news sources are also sensationalist. While most Pyongyang watchers agree Jang was shot dead, Taiwanese news reported he’d been eaten by 120 dogs in front of Kim Jong Un and 300 government ministers in an hour-long death. Feinstein also pointed to a globally syndicated article before Jang’s trial that precipitously claimed www.kcna.kp had cleared out all Jang articles, when in fact articles mentioning Jang were still up. Basically, KCNA “has a bad search function”, said Feinstein.

While the case provides a tantalising view of what the Soviets might have done in the Internet age, it has also pushed out of the headlines another North Korea story, the release of American tourist Merrill Newman who had been held in North Korea since October on charges of “espionage” relating to his military service in Korea during the 1950-1953 war. Newman, who had gone to North Korea as a tourist, said he had not understood quite how far the North Korean state does not consider the war to be over – something arguably partly attributable to the US media barely ever mentioning the conflict, despite the country still being not at peace with North Korea.

Ironically, KCNA Watch has been blocked in South Korea since 25 October. Visitors to the site hit a Korea Communications Standards Commission (KSCS) blocking screen that says “connection to this website you tried to access is blocked as it provides illegal/hazardous information,” under the 1948 National Security Act, which restricts anti-state acts or material that endanger national security, including all printed and online matter from Pyongyang. Civilians seeking to analyse KCNA material in South Korea need official clearance, with the data viewed under armed guard and deleted immediately afterwards, said Feinstein. The block extends to foreign embassies in Seoul and is under increasing criticism as a blanket weapon for stifling dissent. In August the UN special rapporteur on human rights Margaret Sekaggya called it “seriously problematic for the exercise of freedom of expression”.

Sybil Jones

2 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Pakistan, Politics and Society

Urooj M, a former DJ on a Pakistani FM radio channel, also a film aficionado, was incredulous when she found the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) had blocked the Internet Movie Database (IMDb).

She tweeted: “SERIOUSLY #PAKISTAN, WHY ON EARTH WOULD YOU BAN #IMDB!!! COME ON, SERIOUSLY!!!???!!!! #FirstYoutubeNowIMDB #WTF.”

This widely used online entertainment news portal, a prominent source of reliable news and box office reports regarding films, television programmes and video games from all over the world, was blocked on 19 November, but the ban was lifted by 22 November.

Pakistan is notorious for blocking websites. It has banned more than 4,000 websites for what it considers objectionable material, including YouTube, in 2012 for a film that was deemed blasphemous by Muslims around the world. In 2011, in a particularly ill-thought-out move it announced censoring text messages containing swear words. In 2010, after a decision by the Lahore High Court, Facebook was blocked as a reaction to the ‘Everybody Draw Muhammad’ page that was seen as offensive to the prophet.

Users were given no reason for this sudden and selective ban. However, Omar R. Quraishi, a journalist had tweeted: “PTA official declined to give specific reason for ban on IMDB – said is placed for 3 reasons: “anti-state”, “anti-religion”, “anti-social”.

While these “targeted bans” are small irritants in his life, as he can easily by pass them, Ali Tufail, 26, a Karachi-based lawyer, finds them wrong on principle as he sees them infringing upon the fundamental rights of the citizen as given in Article 19 and 19 A of Pakistan’s Constitution.

He said the government must give users sound “reasons” why they block a certain website and “what benchmarks or what standards are used to come to the decision to enforce these sudden bans” and if there is a committee that takes these decisions, “we must be told who these people are.”

The same was endorsed by Nighat Dad of Digital Rights Foundation (DRF). “We strongly oppose any form of censorship employed on citizens, curbing their basic right to information.”

However, netizens believe the ban was enforced to block the movie trailer for The Line of Freedom, a film that highlights the issue of the crises in Balochistan province showing Baloch separatists abducted by Pakistani security agencies without charges in a bid to stamp out rebellion.

“Our team did a quick survey with the help of tweeters around the country,” said Dad. “We checked various other movie titles but only Line of Freedom seemed to be blocked on IMDb and several other websites were accessible otherwise.” The DRF termed it an “unprecedented event” because the government had “used all sorts of means to curb the dissidents’ views” from Balochistan.

“I didn’t even know there was a movie by this title which was giving the government so much heartburn and so I just had to see what was so unsavoury that the government had to block the entire website,” said Dad who watched the whole 30 minutes or so of it by circumventing the various firewalls. “This is what happens, when you forcibly close the internet, word gets around and people get curious!”

Malik Siraj Akbar, editor of the online Baloch Hal, who sought asylum in the United States, is not surprised at the ban. His own newspaper was blocked in November 2010 and even now the ban has not been completely lifted, he says. “Since 2010, it has been available in some parts of the country and not others and access has not been very consistent,” he said adding there were hundreds of other Baloch websites, “mostly those supportive of the nationalists that have been blocked”.

But Tufail added: “This is one battle which the government would find difficult to win as newer, maybe more objectionable [to Pakistani state] websites, will keep popping up which they would never be able to keep pace with,” terming such bans an “exercise in futility”.

There could be some truth in the story of the ban on the Baloch film. Because their voices remain unheard, several family members made a 700km journey on foot from Quetta to Karachi to see if that would make a difference.

Naziha Syed Ali, a journalist at English-language daily Dawn, had recently visited Awaran, a stronghold of the separatists in Balochistan, which had been badly affected by the earthquake on September 24. She said she got a sense of “hostility expressed mainly towards the army and paramilitary rather than Pakistan per se. Then again, the army is seen as a symbol of the country, so it’s pretty much the same thing.”

Ali said “More than fear, they don’t want to take help from what they see as an occupation force.”

According to her the “feelings of alienation have been greatly exacerbated by the issue of the missing people and the kill-and-dump tactics”.

In addition, while Ali found there to be “sufficient food for now”, there was dire need for health services and proper shelter “as the tents that have been distributed are not warm enough for winter”.

The problem is the army is not allowing international and local non-governmental organisations to carry out any relief work there. Instead, the charities run by religio-political organisations and even banned outfits are seen freely roaming about. For years, the state has kept a stony silence over the issue of the disappearances of the Baloch nationalists. Rights group say if the state lets the various organisations into the region, their dark secrets about grave human rights abuses, for now a national shame, may become a problem for it on the international front.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

28 Nov 2013 | Middle East and North Africa, News and features, United Arab Emirates

An American citizen is being held in a maximum-security prison in the United Arab Emirates after posting a satirical YouTube video. He is the first foreign national to be charged with the country’s draconian cybercrimes decree.

Shezanne Cassim (29) posted a mock documentary spoofing youth culture in Dubai. For this he has been charged, among other things, with violating Article 28 of the cybercrimes law. This bans using “information technology to publish caricatures that are ‘liable to endanger state security and its higher interests or infringe on public order’” and is punishable by jail time and a fine of up to 1 million dirhams ($272,000). The video was posted on 10 October last year, and the law only came into force over a month later, on on 12 November.

Cassim, an American citizen who moved to Dubai 2006, was arrested on 7 April this year and had his passport confiscated. A trial date has not yet been set, and a spokesperson for his family says he has been denied bail on three occasions. He is currently being held in al-Wathba prison in Abu Dhabi, together with a number of other foreign nationals who took part in the video but who wish to remain anonymous.

Rori Donaghy, Director of the Emirates Centre for Human rights said in a statement that the case has “worrying implications for all expatriates living and working in the UAE.”

“Cassim has been thrown in prison for posting a silly video on YouTube and authorities must immediately release him as he has clearly not endangered state security in any way.”

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.