18 Mar 2015 | Magazine, mobile, News, Volume 44.01 Spring 2015

Women’s Voices by Meltem Arikan

Index on Censorship magazine’s editor, Rachael Jolley, introduces a special issue on refugee camps, looking at how migrants’ stories get told across the world, from Syria and Eritrea to Italy and the UK

Nothing is national any more, everything and everyone is connected internationally: economies, communication systems, immigration patterns, wars and conflicts all map across networks of different kinds.

Those linking networks can leave the world better informed and more aware of its connections, or those networks can fail to acknowledge their intersections, while carrying as much misinformation as information.

Where people are living in fear a connected world can be frightening, it can carry gossip and information back to those who pursue them. Decades ago, when people escaped from their homes to make a new life across the world, they were not afraid that their words, criticising the government they had fled from, could instantly be broadcast in the land they had left behind.

It is no wonder that in this more connected world, those fleeing persecution are more afraid to tell the truth about what the regime that tortured or imprisoned them has been doing. While, on the one hand, it should be easier to find out about such horrors, the way that your words can fly around the world in seconds adds enormous pressures not to speak about, or criticise, the country you fled from.

That fear often produces silence, leaving the wider world confused about the situation in a conflict-riven country where people are being killed, threatened or imprisoned. The consequences of instant communication can be terrifyingly swift.

Yet a different side of those networks, new apps or free phone services such as Skype, can provide some help in getting messages back to families left behind, giving them some hope about their loved ones’ future. That is one aspect that those in decades and centuries past, who fled their homelands, could never do. In the late 19th century, someone who escaped torture in Russia and travelled thousands of miles to the United States, might never speak to the family they had left behind again.

Communication has been revolutionised in the last two decades – where once a creaky telephone line was the only way of speaking to a sister or father across a continent or two, now Skype, Viber, Googlechat, and others offer options to see and speak every day.

In this issue’s special report Across the Wires, our writers and artists examine the threats of free expression within refugee camps, and as refugees desperately flee from persecution. Sources estimate that there are between 15.5 and 16.7 million refugees in the world today. Some are forced to live in camps for decades, others are fleeing from new conflicts, such as three million who have already left Syria. Many of us may know someone who has been forced to flee from another regime, those that don’t may in the future, and have some understanding of what that journey is like.

In this issue, writer Jason DaPonte examines how those who have escaped remain worried that their words will be captured and used against their families, and the steps they take to try avoid this. He also looks at “new” technology’s ability to keep refugees in touch with the outside world and to help tell the story of the camps themselves.

Italian journalist Fabrizio Gatti spent four years undercover, discovering details of refugee escape routes and people trafficking. In an extract from his book, previously unpublished in English, he tells his story of assuming the identity of a Kurdish man Bilal escaping torture, and fleeing to Italy via the Lampedusa detention camp, and the treatment he encountered. He speaks only Arabic and English to camp officials, but is able to hear what they said to each other in Italian about those seeking asylum. He uncovers the inhumanity and lack of rights those around him experienced in this powerful piece of writing.

Some of our authors in this issue speak from personal experience of seeking refuge, not speaking the language of the land they are forced to move to, and the steps they go through to resettle and be accepted in another land. Kao Kalia Yang’s family fled Laos during the Vietnam war, moving first to Thailand and then to the United States. She remembers how the family struggled first without understanding or speaking in Thai, then the same battles with English once they settled in the United States.

Ismail Einashe, whose family fled from Somaliland, talks to those who have escaped from one of the most secretive countries in the world, Eritrea. Einashe talks to Eritreans, now living in the UK, who are still afraid to speak openly about the conditions at home for fear of retribution.

The report also examines how the global media portrays refugee stories, the accuracy of those portrayals and how projects such as a new Syrian soap opera, partly written by a refugee, are giving asylum seekers and camp dwellers more power to tell the stories themselves.

But when people are escaping danger, the natural inclination is to stay quiet and under the radar. Some bravely do not. They intend to alert the world to a situation that is unfolding, and to attempt to protect others. Our report shows how much easier it is for the world’s citizens to find out about terrible persecution than it was in other eras, but how those communication tools can be turned back on those that are persecuted themselves. The push and pull of global networks, to be used for freedom or to silence others, is an on-going battle and one that we can only become more aware of.

Order your digital version of the magazine from anywhere in the world here

© Rachael Jolley

27 Jan 2015 | About Index, Awards, mobile

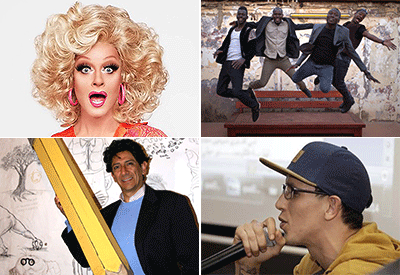

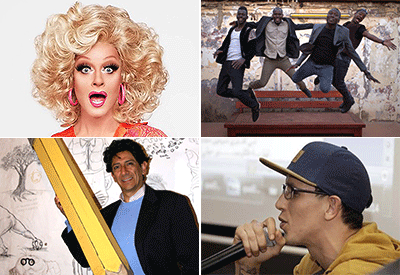

From top left: Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla, Safa Al Ahmad, Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat and Lirio Abbate are among the Index Freedom of Expression Awards nominees for 2015.

A journalist under 24-hour protection because of his reports into the Italian mafia, an Ecuadorian cartoonist facing prosecution for mocking a congressmen’s pay packet, and lawyers who challenged Turkey – and won – over its social media ban, are among those shortlisted for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards this year.

Drawn from more than 2,000 nominations, the shortlist celebrates those at the forefront of tackling censorship and threats to freedom of expression. Many of the 17 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution.

“The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise some of the world’s most courageous journalists, artists and campaigners,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index. “These individuals and groups often work in isolation, with little funding or support, but they are all driven by the vision of a world in which everyone can express themselves freely – no matter who they are or what they believe.”

Awards are offered in four categories: journalism, arts, campaigning and digital activism.

Those on the shortlist include Lirio Abbate, an Italian journalist whose investigations into the mafia mean he requires constant protection; Safa Al Ahmad, whose documentary exposed details of an unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia; radio station Echo of Moscow, one of Russia’s last remaining independent media outlets; and Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan reporter repeatedly prosecuted for his work exposing government and industry corruption.

Arts nominees include Ecuador’s censored cartoonist Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla – who has for more than 30 years critiqued and lampooned the country’s authorities; Moroccan rapper Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, whose music challenges poverty and government corruption; Rory “Panti Bliss” O’Neill, a Dublin-based drag artist who speaks out against homophobia; and Malian musicians Songhoy Blues, who fled their country after music was banned. Guitarist Garba Touré was threatened with having his hand cut off.

In the campaigning category, nominees range from lawyers Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, who played a key part in overturning Turkey’s social media ban last year; to innovative German anti-Nazi group ZDK; to Amran Abdundi, working on the treacherous Somali-Kenya border to help women and girls who are frequently victims of violence, rape and murder. They also include Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar who is working to develop a free media in Afghanistan, and The Union of the Committee of Soliders’ Mothers of Russia – a group dedicated to exposing stories of Russian soldiers, killed in the Ukraine conflict, which the Russian government denies.

The digital activism category, which is decided by public vote, includes investigative news outlet Atlatszo.hu, which is using freedom of information requests to hold the Hungarian government to account; Nico Sell, a US-based entrepreneur and online privacy activist; online map Syria Tracker, which is providing reliable data on human rights abuses in Syria; and Valor por Tamalipas, a crowd-sourced news platform set up to fill a void created by the region’s drug cartel-induced media blackout.

The shortlisted nominees:

Arts

Panti Bliss (Ireland)

Songhoy Blues (Mali)

“Bonil” (Ecuador)

“El Haqed” (Morocco)

More details

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi (Kenya/Somalia)

Zentrum Demokratische Kultur (Germany)

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar (Afghanistan)

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak (Turkey)

Soldiers’ Mothers (Russia)

More details

Digital Activism

Syria Tracker (Syria)

Nico Sell (USA)

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky (Hungary)

Valor por Tamaulipas (Mexico)

More details

Journalism

Rafael Marques de Morais (Angola)

Safa Al Ahmad (Saudi Arabia)

Lirio Abbate (Italy)

Echo of Moscow (Russia)

More details

This article was posted on 27 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Dec 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Statements

Index on Censorship joins the net neutrality coalition, a global coalition of organisations and users who believe that the open internet has enabled countless advances in technology, health, education and business, and that it must remain open for all.

Today, the open internet is endangered by powerful service providers seeking to become gatekeepers who decide how users can access part of the internet.

We believe that we have to enshrine net neutrality into law so that the internet remains a platform for free expression and innovation.

“A free and open internet is vital for free expression,” said Index Chief Executive Jodie Ginsberg. “We must defend net neutrality to ensure everyone has equal access to the channels that have become crucial to so much of modern information exchange.”

Join us and find out more at http://www.thisisnetneutrality.org/

Watch the video below on how net neutrality works:

12 Nov 2014 | Events

In the 1980s, Stewart Brand declared that “information wants to be free”. The phrase became a slogan for technology activists, who argued that tech can liberate information from expensive patents and help further the ever expanding limits of human knowledge. As a part of the BBC Radio 3 Free Thinking Festival, Rana Mitter tests the promises of the internet to spread ideas quickly and democratically. Catch up online with this event featuring:

- Dr Rufus Pollock (Founding President of the Open Knowledge, an international non-profit organisation that promotes making data and information accessible)

- Jodie Ginsberg (Chief Executive of Index on Censorship)

WHERE: BBC Radio 3

WHEN: Thursday 20 November 2014, 10:00pm (then on iPlayer)

TICKETS: Listen live here