8 Aug 2018 | News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102049″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]When Turkish forces attacked Kurdish villages in the southeast of the country in 2016 after the collapse of a ceasefire between Ankara and the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) in July 2015, journalist Nurcan Baysal was there to document the human rights violations. The state declared military curfews, cut off electricity and water supplies and then began bombing civilians in their homes.

“The Turkish media say only terrorists were killed in the basements of Cizre, but 54 of them were students from Turkish universities who went there just to show solidarity and tell the Kurdish people ‘we are with you’,” Baysal tells Index on Censorship. “The security forces burnt them alive — they didn’t want them to return.”

Among the dead were Kurdish fighters, but also journalists and civilians, including children. “With the shooting and bombing, it became too dangerous for people to go outside. Some old people died because they didn’t have enough food.”

Baysal, a Kurdish human rights activist and journalist from the Kurdish-majority province of Diyarbakir, says it was too dangerous even to retrieve those killed from the streets. The children of one dead woman tried in vain to keep dogs from her body by throwing rocks.

“People say things in Turkey are bad, and they are right, but they think it’s the same situation all over the country,” Baysal says. “In the southeast, we aren’t just talking about journalists being locked up. Right now in one area, there are 50 dead bodies still on the ground; they are being eaten by animals.”

Baysal’s political awakening came in July 1991 when the tortured body of her neighbour, Vedat Aydin, a prominent human right activist and politician, was found under a bridge after he was been taken into police custody. She then began her career working for the UN Development Programme where she focused on poverty and strengthening women’s organisations in Diyarbakir. During this time she established a number of NGOs focusing on the forced migration of the Kurdish people. Her experience saw her take up an advisory role in the Northern Irish peace process in the late 1990s.

Baysal was back in Ireland in May 2018 to collect an award from the Irish human rights organisation Front Line Defenders, who named her its Global Laureate for Human Rights Defenders at Risk for 2018.

(Photo: Jason Clarke for Front Line Defenders)

“There was a lot of coverage in the Irish papers, which is good because you don’t tend to read much coverage of Kurdish issues elsewhere,” she says. “The international community does not pay attention to the violence against the Kurdish people. The international community is indifferent.”

In March 2013 a new peace process began, but by May 2013 Baysal began to see an increase in village guards, paramilitaries hired by the Turkish government to oversee the inhabitants, in half of the areas she works in. “In those villages we were trying to implement a development programme, but I could see something was wrong and I knew what that meant for peace.”

For her work covering what she says aren’t just ordinary human rights violations, but war crimes in Turkey’s southeast, Baysal has endured threats, intimidation, travel bans and worse. Legal cases have been taken against her, two of which have gone to court. “One of these was for reporting on what I witnessed in Cizre, such as the used condoms left by Turkish soldiers which show the horrible things they did there,” she says. “There were other journalists there but they decided not to write about it, and the Turkish media has closed their eyes, so I knew what I had to.”

Her work was on this issue was censored. “In Turkey there is usually a process if you want to censor something, but in this case there was no process, they just did it,” she says.

The court case lasted two years, at the end of which she was given a ten-month prison sentence — one she wouldn’t serve as long as she didn’t re-offend — for “humiliating Turkish security services” with her article and accompanying photographs. She told the judge that she has even worse photographs that she didn’t publish out of respect for the victims.

When Turkey began its military incursion, code-named Operation Olive Branch, into Afrin, Syria, which was under the control of Kurdish YPG forces, in January 2018, Baysal criticised the Turkish government and called for peace in a series of five tweets. Then, on Sunday 21 January 2018, while she was watching a film with her children at her Diyarbakir home, she heard a noise that she couldn’t understand at first. “It took me a moment to realise the noise was coming from my door,” she says. “They tried to break it down, but it was so strong that the wall around it crumbled and in came a 20-man special operations team with masks and Kalashnikovs. I don’t know what they were planning to find in my home, but when they did this they were sending a message and a lot of other people got scared.”

Baysal spent three nights in prison before being bailed following a series of protests, not just locally, but internationally. Three hundred supporters gathered outside the detention centre, she received the support of Kurdish MPs and her case was raised in the European Parliament.

Baysal now awaits trial on charges of “inciting hatred and enmity among the population”. If convicted, she faces up to three years in jail.

A lot of Turkish newspapers now refer to Baysal as a terrorist, she explains. “The word ‘terrorist’ is used so much that right now half the country are terrorists. Academics for Peace? Terrorists. Students? Terrorists. Doctors? Terrorists. Those who use the word ‘peace’? Terrorists.”

“Kurdish society is a colonised society. Two Kurdish wedding singers were put in prison because they were singing Kurdish songs. A student has been imprisoned for whistling in Kurdish. I really don’t know what it means to whistle in Kurdish,” she laughs.

Baysal explains how in many Kurdish areas, Kurdish mayors have been imprisoned, only to be replaced by government-appointed administrators. In one part of Diyarbakir, Kurds had planted flowers in yellow, red and green, the colours of the Kurdish flag. “One day we woke up and they had taken the heads off all the flowers. Why? The administrators said ‘these are the colours of the PKK’.”

In the November 2015 general election in Turkey, the leftist pro-Kurdish HDP surpassed the 10% threshold necessary to win seats in the new parliament. The effect on the peace process was immediate. The Turkish government saw the process as benefitting only the Kurdish parties, not themselves, Baysal says. “If you ask them now, they will say there is peace, and they are only fighting the PKK, but in their eyes you are PKK if you speak in Kurdish.”

Over the last three years, all Kurdish street signs have been replaced with Turkish ones. “They say ‘those Kurdish signs are PKK’,” Baysal explains. And what about Kurdish media? “Well, we don’t have Kurdish media anymore either, they’ve all been closed.”

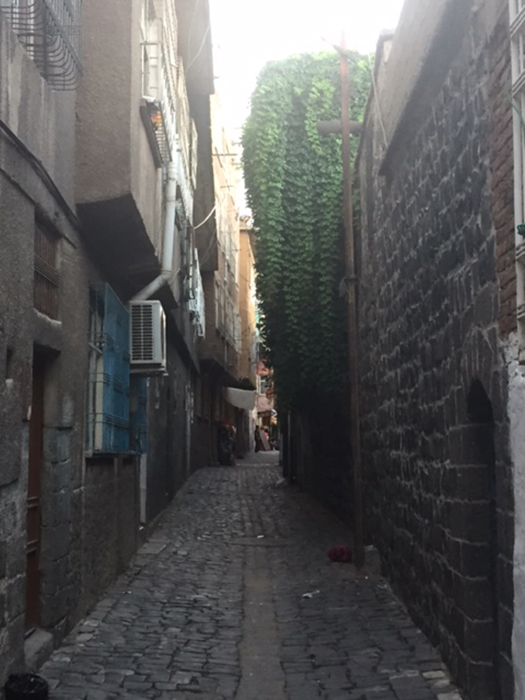

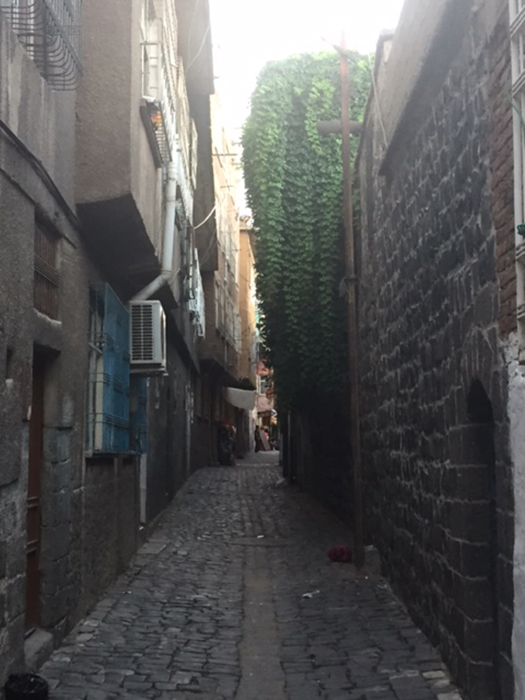

Various neighbourhoods in the Sur district of Diyarbakır have been demolished as part of an “urban regeneration programme”

Turkey’s Kurds have known war for a long time, but this time it is different. Rather than fighting in the mountains, war has now been brought into the cities. Since 2015, Turkish forces have demolished entire Kurdish towns and cities. “This is what happened in Sur, which today it is a flattened area,” Baysal says. “Sur is a city that’s 7,000 years old. It’s part of the history of humanity, not just the history of Kurdish people. The story of Armenians, Assyrians — and it’s been ruined.”

Tens of thousands of Kurds have been made homeless by this destruction, with many making their way to other Kurdish towns and cities, while others have set up camp in tents along roads.

In the 1990s, Kurdish people felt that even though they were at war there was always hope, Baysal explains. “With the peace process there was always the belief that things would get better, but today we don’t have hope — no hope at all in the Turkish state.”

“Having seen what has happened in the last three years and how cruel this state can be, I really don’t know what will happen in the future. Everything is unclear. We don’t know tomorrow or even tomorrow morning. This is how we live now.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to tell the stories of censored Turkish writers, artists, translators and human rights defenders.

Learn more about Turkey Uncensored.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Media freedom violations in Turkey reported to and verified by Mapping Media Freedom since May 2014

[/vc_column_text][vc_raw_html]JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwd2lkdGglM0QlMjI3MDAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjIzMTUlMjIlMjBzcmMlM0QlMjJodHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRm1hcHBpbmdtZWRpYWZyZWVkb20udXNoYWhpZGkuaW8lMkZzYXZlZHNlYXJjaGVzJTJGMTA3JTJGbWFwJTIyJTIwZnJhbWVib3JkZXIlM0QlMjIwJTIyJTIwYWxsb3dmdWxsc2NyZWVuJTNFJTNDJTJGaWZyYW1lJTNF[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1549634009771-626ea240-da95-7″ taxonomies=”1765, 1743″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 May 2018 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100382″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Seda Taşkın had just been sent to Muş, a tiny eastern Turkish city on a fertile plain surrounded by high mountains, to report on a few stories when police started to track her down. Hot on the case, police apparently availed themselves of a time machine, arresting the Mezopotamya news agency reporter late in December half an hour before a prosecutor had even issued an arrest warrant in concert with an informant’s tipoff. Taşkın’s subsequent trial, however, suggests that rather than breaking new grounds in physics, Turkey’s authorities are probably just breaking the law.

Taşkın appeared in court for the first time on 30 April to face charges of “membership in a terrorist organisation” and “conducting propaganda for a terrorist organisation.” The court date, however, exposed serious irregularities regarding her arrest, the treatment she received in custody and the evidence against her. During the hearing at the 2nd High Criminal Court of Muş, Taşkın’s lawyer highlighted the email address used to tip off authorities to the journalist’s alleged crimes.

According to the official document in the case file seen by Mapping Media Freedom’s Turkey correspondent, the email address denouncing Taşkın as a “militant” bore an “egm” extension, signifying the Turkish abbreviation for “general department of police.” Gulan Çağın Kaleli told the court that a mere 20 minutes were required to locate Taşkın and arrest her – a period that’s even less than the time it took to issue a mandatory arrest warrant. Questioning whether the anti-terror unit had, in fact, fabricated the tipoff, Kaleli requested that the source of the email be identified according to its IP number, but the court ultimately rejected the demand.

“The police tipped her off and the state caught her. This was the mise-en-scène,” said Hakkı Boltan, the co-president of the Free Journalists’ Initiative (ÖGİ), a Diyarbakır-based journalistic group that monitors press freedom violations and aids journalists who face legal proceedings in Kurdish provinces.

Taşkın is a journalist based in the city of Van who mainly covers social and cultural news. At the time of her arrest, she was working on several reports, including a story about the family of Sisê Bingöl. Authorities jailed the 78-year-old woman in June 2016 in Muş’s Varto district on accusations of being a “terrorist” before sentencing her to four years and two months in prison. Boltan told MMF that this type of reporting is often considered as threatening to the state as it reveals police violations. “The public has the right to be informed about this unjust imprisonment. This is what Seda was trying to do when she was targeted by the state.”

Ill treatment from police, threats from the prosecutor

Turkish authorities arrested Taşkın on 20 December 2017 before freeing her four days later. The prosecutor, however, filed an objection against the court’s release order. A month later, on 23 January, officers again arrested Taşkın in Ankara, where the journalist had gone to join her family.

In her defense, Taşkın told the court that police subjected her to a strip search after her initial arrest. “When I refused, they said they would force me,” she said via a judicial video conferencing system from Ankara’s Sincan Women Prison Facility, where she remains in custody pending trial. She was subjected to a second strip search before finally seeing her lawyer. “I was also physically beaten when I refused to get in the armoured vehicle. If I’m telling this, it’s because I want the court to take it into consideration,” she said.

The court didn’t appear greatly concerned.

Taşkın was also threatened after her initial release from custody. “The prosecutor told her ‘How can you be freed? You will see, we will file an objection’ in front of her lawyer as a witness,” Kaleli told the court.

The lawyer also said the evidence against her client was restricted to retweets and Facebook shares – mostly of news articles. There is not even a single article written by Taşkın in the case file, she said. “You may not like the agency where my client works. But this agency is still operating legally, and this is about freedom of expression and press freedom.”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”100383″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]Touring villages with her camera

Included in the indictment as evidence was a “package” that a colleague sought to give Taşkın. There was a certain air of mystery to the private Instagram conversation between Taşkın and her colleague, Diyarbakır-based journalist and photographer Refik Tekin, but the item in question was only a fleece – and police could have ascertained the innocence of the matter had they clicked on the embedded link in the conversation.

Tekin told MMF that the pair had merely discussed the logistics of Taşkın receiving the fleece in Muş. He eventually sent the item of clothing to the prison in Ankara after she was jailed, but Taşkın was still unable to obtain it: The fleece is dark blue – a color that is banned in prison because it matches the uniforms of guards.

Tekin said Taşkın loves photography. She would tour villages around Lake Van in search of news and human stories. “She is a very friendly person. People in villages are usually somewhat shy, but they would immediately open up to Seda,” Tekin said. “She took photos of children in villages, women working in fields… Those were beautiful, very touching. They would tell a story. She would be on the top of the world when her photos appeared in [the now-closed newspaper] Özgürlükçü Demokrasi,” he said.

Her close friend Nimet Ölmez, also a Van-based reporter for Mezopotamya, said Taşkın’s picture of two children returning from school with their dirty clothes and large baskets instead of backpacks helped raise awareness about the precarious situation of children living in the impoverished villages of the region. “They were shared on social media for days. So many people called and asked us how they could help.”

But she admits that Taşkın’s love for photography was perhaps a bit on the excessive side. “She would take so many photos that all our memory sticks would fill up. She once went to a village to report on some shepherd. He had around 200 sheep, but Seda still managed to come back with 230 photos – more than one photo per sheep,” she joked. “I really miss fighting for photos, memory sticks and news with her.”

On 30 April, the court ruled against Taşkın’s release on the grounds that she doesn’t use the name on her ID card, Seher, in daily life, even though everyone, including her close family, calls her Seda.

The next hearing will be held on 2 July in Muş – a town that appears in a popular song with the lyrics “the road to Muş is uphill.” Rather than just Muş, it seems the song’s writers were talking about the road to justice in Turkey today.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-file-excel-o” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Media freedom violations reported to MMF since 24 May 2014

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526396916736-92769289-9c57-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Mar 2018 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

İshak Karakas (Photo: Ahmet Tulgar)

İshak Karakaş, the editor-in-chief of a local Istanbul weekly Halkın Nabzı, is an early riser. He is usually up before dawn and back from a long walk, which he takes with an unlikely group of friends from the neighbourhood, by 8 am. This is when he starts checking the news of the day over breakfast while posting impassioned tweets about the morning’s reports.

On 20 January the Turkish military launched an operation into Afrin, a Kurdish-controlled enclave in Syria, arguing that the Kurdish forces in the region are an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which Turkey considers a terrorist organisation. Karakaş, like many others, took to Twitter to criticise the military incursion. He did so using the account @ishakkakarakas_, which has since been closed by his son and lawyer Uğur Karakaş.

“There is not a single Islamic State gang in Afrin. Why are you telling lies?” he asked Turkey’s politicians, who have claimed that the Kurdish forces in Syria are actually ISIS militants. “Don’t believe the TV’s propaganda on Afrin,” he told fellow citizens in another tweet. He also retweeted a post claiming that civilians had been killed in the region at the hands of the Turkish military.

Then they came for him.

“It was about midnight. My dad was sleeping. I wasn’t home, though my mother was. The police came banging on the door; they said they had a search warrant,” says Karakaş, an Istanbul-based defence attorney. His father was arrested on 26 January on charges of “spreading terror propaganda” through Twitter. He is now in Silivri Prison, with no indictment in sight.

A country with no humour

Karakaş certainly wasn’t the only one to feel the ire of the Turkish state at war. According to the Turkish interior ministry, as of 27 February, 845 people had been detained by police for criticising the Afrin operation (or “spreading propaganda of a terror organisation” as the ministry prefers to phrase it) which Turkey has officially named “Operation Olive Branch”. The ministry hasn’t said how many of those detained were formally charged and imprisoned, but judging by the fact that all eight taken along with Karakaş were, according to his court papers, arrested, that number is not likely to be low.

Karakaş was born in Diyarbakır in 1960. He finished primary school and then started working as an assistant to truck drivers at the age of 12. In 1989 he was forced to migrate to Istanbul like many other Kurds at the time, together with his wife Müzeyyen and first-born, Uğur (Azad). The couple’s other children, Umut and Ufuk, were born in the city. “He is a patriot, and he was always a political person,” remembers Uğur Karakaş. Although he was in the logistics trade until his company went bankrupt following the 2000 financial crisis in Turkey, Karakaş was always engaged in politics and he wrote columns for the pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem and socialist Evrensel.

Life in Istanbul and Halkın Nabzı

Despite being in commerce after he moved to Istanbul, he found the time to complete secondary and high school through distance learning. According to his interrogation log, he is currently in his second year obtaining a sociology degree from Turkey’s distance learning university Açıköğretim. He also made sure that his children had a better chance at life: one is a lawyer and the one is a doctor. His youngest is attending an undergraduate computer engineering programme.

“Even before he was a journalist, he was always interested in the country’s problems,” says Ahmet Tulgar, a veteran Turkish journalist who has been publishing Halkın Nabzı with Karakaş for more than six years. Their paths had crossed at panels and meetings before they formally started working together. When Karakaş was out of the logistics business and Tulgar left his day job at the BirGün newspaper in the second half of 2000s, the two men started an advertising company in İstanbul’s Maltepe district — which is where Halkın Nabzı is published today.

“He is a family man. He would come to work after his morning walk and go home straight in the evening. In 2013 we decided to publish a local newspaper together, but it wouldn’t be one of those local publications which only report on where the mayor had dinner or on the recent affairs of the powerful people in the community,” Tulgar says.

And as such, Halkın Nabzı came to life. Distributed on the Anatolian side of Istanbul and funded by local businesses and municipalities, the weekly newspaper has a circulation of 10,000 copies. Given the vision and background of its founders, Halkın Nabzı’s emphasis on quality journalism is not a surprise: the paper values its independence above all else. It brings local stories to the forefront while maintaining its relevance to the national conversation. According to Tulgar, Halkın Nabzı’s editorial policy is defined by a “peace journalism that encompasses all segments of society and that uses a style which can be comprehended by all societal segments”. “İshak’s tweets are not reflective of our editorial policy of course,” he is quick to add.

A family man

“Let alone putting such a man in jail, they should reward him for having found the formula for peace in this country,” says Tulgar, who adds that the participants of Karakaş’s morning (Tulgar, who is happy to sleep in in the morning, isn’t one of them), come from very diverse and opposing political backgrounds.

“He is a man of peace. I guess you can say that about anyone, but he wanted to be a soldier of peace. Unfortunately, they have put such a man in jail,” Tulgar says. He also jokingly complains that he and Uğur have had to eat fast food for the past few weeks. “He always fixed lunch for us in the office. Sometimes the people in our building would come ask if they could have some of what he has cook if they couldn’t find something good to order on a particular day.”

For Tulgar, Karakaş’s absence is much more than missing a hearty and healthy lunch. When the two started the newspaper, they were mostly on their own for the first couple of years. “We have worked together for so long, of course it is hard,” he says, slightly bitter at his friend for tweeting “irresponsibly”.

What Tulgar doesn’t say is how he and his now-imprisoned friend have shared the everyday stress of launching a publication and how they had to brave the anxiety of trying to produce good journalism in one of the most dangerous countries for the profession. The two men have been in battle together, and now one is in prison.

Even if Karakaş is convicted, he would be released because although propaganda is punishable by a two-year sentence, such sentences are usually suspended under Turkey’s criminal procedures, according to Uğur Karakaş.

“He has a huge family. He is a grandfather and another grandchild is on the way. Uğur will get married this summer,” Tulgar added.

In Turkey’s wider reality, where 153 journalists are in prison and six were sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole only two weeks ago, knowing that Karakaş may be released at his first trial is comforting.

Tulgar slows down, speaking softly: “Cumhuriyet’s Murat Sabuncu, who is a gem of a man, Ahmet Şık, who is such a great journalist who has never chased personal interest or fame, and Akın Atalay are in prison. Osman Kavala is also in prison. There are so many great people in prison, it is embarrassing to complain ‘oh my friend has been in prison for one-and-a-half months.’ ”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”pagination” items_per_page=”2″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1520255755875-dae306ff-b8c0-4″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Aug 2017 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

The district of Sur was the first settlement in Diyarbakır, which, according to some sources, has been inhabited for five thousand years and hosted 33 civilisations. The area’s architecture — a rich combination of churches and mosques, mansions and modest homes from different eras — is evidence of its long history and well-established community.

Since June 2016, parts of Sur have demolished as part of an “urban regeneration programme”. In the first stage, homes in the Sur neighbourhoods of Lalebey and Alipaşa were demolished. In the process, the primarily Kurdish communities were destroyed: some families moved away, their connections to their personal history severed; others stayed put, clinging to their homes and their lives in the neighbourhoods with a tenacious resistance to being erased.

The 2016 demolitions were the latest phase in a long process that began in 2009. That’s when the Mayoralties of Diyarbakır and Sur signed an agreement with Turkey’s Environment and Urban Planning Ministry and the Mass Housing Administration to replace the local housing stock with new homes in a style appropriate to the area. Beginning in 2011 with the bulldozing of homes of houses in the Alipaşa neighbourhood, the residents have been at odds with a government they see as inattentive and arbitrary.

During the 1990s, there were violent clashes between Turkey’s military and armed groups aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Thousands of villages were evacuated by state forces. Displaced people became impoverished when they settled in the city of Sur.

When the displaced began arriving in Sur, new housing was built that quickly overwhelmed the area’s mosque and architecture.

Historic buildings were destroyed in order to build housing for the displaced and the area quickly became a slum. In a short time, some of the new housing became unhealthy and unstable.

With neighbourhoods of historic buildings, narrow streets and local culture, the city of Sur would have lost these features through its urban regeneration project. Moreover, the money set aside to buy properties was not enough to allow people to start new lives elsewhere. As a result, the local government suspended the project.

Though the demolitions had been halted because the inhabitants of the area did not want to evacuate their homes and civil society organisations had objected to the destruction of the area’s history and community, an emergency decree issued after the failed July 2016 coup restarted the urban regeneration project.

In May 2017, authorities told residents of Sur’s Lalebey and Alipaşa neighborhoods to evacuate their homes. Families that resisted were told they would be forcibly removed. In the face of the threat, some families left the area. Those that remained had their water and electricity turned off.

Residents of Lalebey and Alipaşa have used the walls of the neighbourhoods to make it clear they do not want to leave their homes.

Residents of Lalebey and Alipaşa have used the walls of the neighbourhoods to make it clear they do not want to leave their homes.

Cumali, sitting in front of his evacuated house, did not want to leave Sur. He has been moved to temporary housing on a road that has not yet been demolished. Cumali says: “I was born in Sur, I grew up, got married. Let us relax. I want to die in Sur.”

Mevlüde Ak was born and grew up in a house in Sur. She gave her house in Sur to her married, unemployed son. She lives with her husband in their small shop. After closing time, they put down beds on the floor and sleep there. Mevlüde Ak says: “They offered me 60,000 Lira for our house. This money would not be enough for us to buy a new home. We’re not leaving. If they wish, let them bring it down on top of us.”

Aynur Güneş’s husband died years ago. She has no children. She lives by selling things like chocolate, gum, crisps in front of her house because it is close to a school. She explains why she does not want to leave Sur as follows: “I know nothing will happen to me here. If something happens: if I fall ill, for example, my neighbours will immediately come to help me. That’s how we grew up in Sur. If I have to live in an apartment I will die.”

Civil society organisations, supported by artists, journalists and politicians, have banded together with Sur residents to fight the ongoing destruction in the neighbourhoods. The campaign is helping to organise petitions and community gatherings, like this one breaking the fast during Ramadan.